Features

False information that should not be ignored

Published

1 year agoon

Since the beginning of the new financial year, the 485 visa adjustment has come into effect and has sparked a lot of discussion. After all, this move by the government potentially affects the future of many international students.

Last week, a protest organised by some international students, which did not receive much attention from international students or the community, was described as a protest by tens of thousands of people on some Chinese social media platforms. A small piece of news has become fake news in the Chinese media, which makes us reflect on how to provide more valuable and truthful news to our readers.

The Seriousness of the False News Problem and its Overwhelm

It is a basic human desire to get true information. And news is based on the true reflection of objective facts as the nature of the characteristics. However, with the rapid development of communication technology and the arrival of the new media era, the problem of false news, which has long plagued the news media industry, has become more and more serious. Especially nowadays, everyone has a microphone, all members of society are intentionally or unintentionally involved in the dissemination of news and information in the process – as long as there is a smart phone, you can take pictures, video or voice a key to disseminate the so-called information, objectively leading to the emergence of false news.

The rapid development of the Internet and the convenience of the application of communication technology, so that almost all members of society can participate in the dissemination of information, but the norms of communication have not been accompanied by the rapid development of communication technology and the establishment of one of the direct consequences is the spread of false news. The dissemination of news and information is a professional behaviour, which needs to follow the basic norms of news and information production and dissemination. However, for many members of the society, these norms have not become the threshold of their participation in the dissemination process, and at the same time, they also lack professional knowledge of news media and news works, thus, there is a wide space for the popularity of false news.

In today’s society with the rapid development of new media, there is fierce competition among the media, especially the new media which takes traffic as an indicator, and they do not hesitate to finish their reports with hearsay and fabrication, and write whatever they can to attract eyeballs. As a result, the quality of information cannot be guaranteed. Sometimes, when a hot story breaks out, major media outlets republish it among themselves. In some hotspot events, lax gatekeeping by the first media resulted in false news, which led to dominoes of errors by the reposting media, resulting in the collapse of public trust in the media. In addition, with the use of artificial intelligence, virtual reality and other technologies, the production of fake news on the Internet has become even faster and easier, making it difficult for ordinary people to distinguish the authenticity of graphics and video content.

Let’s take a look at this process from the perspective of a news story about 485 visas that turned into fake news.

485 Visa Policy Adjustment Causes Controversy

From 1 July this year, the maximum age limit for applying for an Australian Graduate Temporary Visa (Type 485) will be reduced from 50 to 35 years old. For PhD graduates and Masters by Research graduates, the maximum age limit to apply for a Class 485 visa will remain at 50 years old. With the implementation of the new policy, many international students are worried that they will lose the opportunity to work in Australia and be forced to return home. The change has not only taken thousands of international students by surprise, but has also sparked widespread debate about Australia’s migration strategy amongst industry and migration experts.

The 485 Graduate Visa was introduced in 2007 and was originally intended to allow university or college graduates who intended to stay in Australia but did not meet the work experience requirements for skilled migrants to work in Australia for a period of time to make it possible for them to meet the relevant requirements. Initially, there was less than 24 months, and visa holders who could not apply for a different visa before the end of the visa were required to leave Australia.

The 485 Graduate Work Visa has now become an important factor in attracting international students to Australia. Previously, 485 visa holders were able to work full-time in Australia as a primary or secondary applicant with a high degree of flexibility, making this type of visa one of the most attractive temporary work visas in the world. Particularly in the absence of stringent skills requirements, employer sponsorship and minimum wage standards, some students have used the visa to gain valuable work experience on which to apply for permanent residence. At the same time, more people are using the visa to gain up to eight years of work experience in Australia by taking a simple two-year diploma course. In South Asian countries, many study abroad consultants have used this as a way of recruiting large numbers of students to become permanent workers in Australia. However, policy changes in the new financial year have shattered many of these dreams.

International students coming to Australia seem to follow an unwritten rule: study – get a transitional visa after graduation – get a job – apply for permanent residence, but this is more like the brainwashing effect of the study migration industry on international students, and the agents don’t share all the information with these students who don’t have a good understanding of Australia’s policies. The agent will not share all the information to these students who have no idea about Australia’s policies. The language bottleneck, cultural differences, and the financial and psychological pressure of high tuition and living costs have left international students with no time to understand Australia’s immigration policy. In fact, Australia’s immigration policy is not necessarily linked to studying in Australia, and many professions are not on the list of immigrant-eligible occupations. Due to the massive influx of international students in recent years, many of the professions on the list have been taken down, resulting in many international students investing a lot of time and money in the early stages of the cost, but it is still a basket case; however, the immigration agents have already made a lot of money.

The alarmist talk is aimed at creating chaos in the world

The tightening of 485 visas is expected to affect nearly 20,000 students, and some are worried that they will not be able to stay in Australia once their visas expire. Students taking part in protests in Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra told SBS they had expected the 485 visas to provide them with the necessary work experience to stay in Australia, and indeed some have recently organised vigils in various cities to demand a fair transition period. The problem is that the protests, which were only attended by a handful of students, have been described by some Chinese-language WeChat platforms as ‘tens of thousands of students protesting against the Australian government’s tightening of the 485 visa on 17th October! — No doubt it is a proper headline, even though there are photos showing that only a few students were at the protest.

This is not an isolated case. Just this past weekend, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia experienced a major malfunction, with multiple accounts being charged repeatedly, resulting in overdrafts on some accounts. When it comes to Chinese language internet platforms, it’s ‘the sky is falling! A large number of Chinese Australians have been hit by the malfunction. ‘A large number of Chinese Australians have had their bank accounts emptied!’ It’s a complete statement – based on certain facts, but exaggerated in order to attract attention and increase traffic. This is a typical practice in the Chinese language media, whereby the English language reports are laundered, and then the information is selected, filtered and presented in a more exaggerated way, only that the information has already been seriously distorted when it reaches the recipients – the readers.

The essence of WeChat is the title

Information is different from knowledge in that knowledge helps us to live and work, whereas information enables us to know and make decisions. Modern people value information at the expense of knowledge, striving to know everything without distinguishing the details of what they know in order to make a judgement, and so a great deal of information in the form of headlines has appeared on mobile platforms. This is the nature of WeChat’s information.

When people read the headlines, they think they already know what is going on without looking at the details. So the headlines become exaggerated and easy to remember, and at the same time create room for false information. In a short period of time, the content of an incredible headline can become something that everyone believes.

There are currently over 800,000 WeChat users in Australia. Due to language barriers, WeChat has become an important source of information for Chinese Australians, but it’s important to be vigilant about this kind of misinformation. After all, the information that people are exposed to on a daily basis can have a huge impact on their views and political opinions. Imagine if people left China and still received information via WeChat or watched Chinese TV programmes even though their bodies had been turned over the wall, it would be difficult to see a huge change in the way people think before and after leaving the country – after all, the source of information would still be the same. As WeChat becomes indispensable, more users will enter a kind of information vortex, meaning that no matter where they live in the world, they will still be living under the same set of narratives and censorship as they do in mainland China. This will do more harm than good to the integration of new Chinese immigrants into the Australian community.

The two examples mentioned above, at a glance, you would believe that the 485 visa affects the right of many people to stay and work in Australia, without thinking whether granting a 485 visa means that the Australian government agrees that these people can stay and work in Australia for a long time? Fake news is so destructive to the society. The second example makes you think that the Federal Bank of Australia is deliberately targeting Chinese customers, but in fact, different people are affected and there is no question of targeting the Chinese. Of course some Chinese were inconvenienced by the incident, but the focus of the problem was not on the Chinese at all.

Of course, it seems to be a daily news report that provides this kind of content, but the practitioners may not be able to pass the minimum standard of journalism, but nowadays, social media platforms are flooded with this kind of unintentional false news.

Government regulation is not an option

Like many people around the world, Chinese people now get their news from social media rather than traditional news media. In Australia, there are more than 100 Chinese-language news publics on WeChat platforms that publish news specifically for Chinese Australians. Many of these public numbers push articles about which restaurants are popular, where there are discounts, or other lifestyle topics. However, due to their readership model, they often exaggerate and exaggerate in order to attract attention, and some even create fake news and spread rumours, as their readership determines their advertising revenue. Moreover, the proliferation of fake news is not only a problem for WeChat, but also for Facebook and Twitter. There have been calls for the Australian government to step up its legislative oversight, and recently there have been some signs of this.

Due to the widespread popularity of digital platforms, while they bring unlimited convenience to the audience, they may also become a tool to disseminate misleading or false information that is very harmful to the hands. The rapid spread of harmful misinformation and disinformation poses a significant challenge to the functioning of societies around the world. The Commonwealth Minister for Communications, Mr Rowland, has said that around 75 per cent of Australians are concerned about the harmful effects of misinformation and disinformation. Recently, the Australian Federal Government introduced new laws to address the dangers of misinformation and disinformation in the digital age. Regulators will have the power to impose large fines for misconduct by some major technology companies to combat the spread of misinformation and disinformation on the platforms of technology companies such as Meta and X. The bill aims to provide regulatory support for the spread of misinformation and disinformation on the platforms of technology companies such as Meta.

The bill seeks to strengthen the voluntary code by providing regulatory support. Specifically, the bill will empower ACMA to review the effectiveness of digital platform systems and processes, and will increase the transparency of the measures taken by platforms to protect Australians from misinformation and falsehoods in the use of social media. It is hoped that the new bill will have a binding effect on Chinese-language digital platforms to enhance the verification of information. More importantly, Australia’s mainstream media needs to reach out more to the Chinese community and international students to ensure their voices are heard, otherwise it’s no surprise that ‘bad money drives out good money’. Currently, The Australian, SBS and ABC are the only three mainstream media outlets that produce Chinese-language Australian news. The Chinese community is in dire need of media platforms with a voice from their own community and a conscience to provide better news to the Chinese community in Australia.

More resources for the community

Multicultural communities have always provided information platforms that are more relevant and influential to their own communities. For example, Chinese newspapers were already published in gold mining towns more than 160 years ago during the gold rush era. Community-supported Chinese-language media, while not as exhaustive as the mainstream media about Australian life, did distribute important social and governmental information. Today, there are community radio stations in Australia, and the government encourages immigrant communities to broadcast in their own language to disseminate messages and information about their community, as it is a basic human right for everyone to be able to access information in the language they are most comfortable with.

In today’s information society, this is even more important. Because of the Internet, every multicultural Australian in Australia has the potential to be influenced by information from other countries through the Internet. This information can be distributed in an organised and systematic way with the intention of influencing these communities, or it can be created inadvertently by people but spread due to the misperceptions and limitations of the distributors and their biased attitudes towards things. In any case, if the Australian community is to deal with such a large number of messages and platforms that are so easily created and uncontrollable, the community can only build a more credible, trustworthy and quality information platform on the one hand, so that the right messages are valued by the community on the other. Of course, how to disseminate and enable everyone to enhance the ability to distinguish the authenticity of information also becomes important. Information Literacy and Media Literacy are becoming an important part of the basic life skills of modern people.

Therefore, it is necessary for society to provide more resources in this area. Otherwise, the general public will easily become unable to distinguish between right and wrong, and it will be difficult to reach a consensus when society makes a decision, and there will be no basis for discussion when important decisions are made. In that case, society will have to pay a heavy price in the long run for making wrong decisions.

You may like

This year, the world has continued to pass through turmoil.

Israel has temporarily stopped its attacks on Gaza. I hope that this region, after nearly 80 years of conflict, can finally move toward peace. I remember when I was young, I believed that this land was given by God to the Israelites, and therefore they had the right to kill all others in order to protect the land that belonged to them. I can only admit my ignorance. Yet this did not cause me to lose my faith; rather, it taught me to seek and understand the One I believe in amid questioning and doubt.

December is the time when we remember the birth of Jesus Christ—a season when people would bless one another. Sameway sends blessings to every reader, whether you are in Australia or gone overseas. May you experience peace that comes from God, and not only enjoy a relaxing holiday with your family, but also share quality time together. Our colleagues will also take a short break, and we will resume publication in early January next year, journeying with our readers once again.

While our office will be relocating, the daily news commentary we launched on our website this year will continue throughout this period though. Our transformation of Sameway into a multi-platform Chinese media outlet will also continue next year. It is your support that convinces us that Sameway is not just a publication—it is a calling for a group of Christians to walk with the Chinese community. It is also the blessing God wants to bring to the community through us. We hope that in the coming year, Sameway will continue to stand firm as a Chinese publication committed to speaking truth.

Today, anyone making a request to U.S. President Trump must first praise his greatness and contributions—no different from the Cultural Revolution-style rhetoric we despise. Western politicians call this “political reality.” Russia, as an aggressor, shamelessly claims to “grant” conditions for peace to Ukraine, and other Western leaders must endure and compromise. Australians continue to face economic and living pressures, and immigrants are still scapegoated as the root of these problems, leaving people anxious. Sadly, last week Hong Kong suffered a once-in-a-century fire disaster, causing 151 deaths and the destruction of countless properties—a heartbreaking tragedy. Even more tragic is witnessing the indifference of Hong Kong officials responsible for the incident, and the fact that Hong Kong has now been fully absorbed into the Chinese model of governance—an authoritarian system dominated entirely by “national security” or the will of its leaders, where no one may question the truth of events or demand government accountability.

Yet, in the midst of such helplessness, I still believe that the God who rules over history is the same God who loves humanity—who gave His only Son Jesus to the world to redeem humankind.

Wishing all our readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! See you next year.

Mr. Raymond Chow, Publisher

A massive fire has revealed to the world the hardships Hong Kong society is currently facing. Seven 31-storey buildings—with roughly 1,700 units—were destroyed in a 43-hour blaze, leaving nearly two thousand families homeless. The 156 people who died, including many elderly residents and the domestic workers who cared for them, left their families devastated: most victims simply had no chance to escape because the flames spread rapidly and the fire alarm never sounded. The shocking footage—resembling iconic scenes from a disaster film—circulated online within a single day, prompting many to ask: Is this the suffering now endured by the place once known as the “Pearl of the Orient”?

World leaders offered their condolences to Hongkongers. Chinese President Xi Jinping expressed sorrow for the victims and extended sympathy to their families and survivors. Pope Leo XIV and King Charles III conveyed their condolences; Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese expressed care and support for Hong Kong people. Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing immediately donated HKD $80 million for disaster relief and distributed emergency aid, earning widespread approval. Citizens brought clothes, food, and supplies to the disaster site to help affected residents, showing a spirit of mutual aid in times of hardship.

During the fire, many waited anxiously near the site, hoping their loved ones would emerge safely. For those who reunited with family, there was relief—an ember of hope amid catastrophe. But others were forced to accept, in an instant, that their loved ones had been burned to death, reduced to ashes, having suffered unbearable agony in their final moments. Their grief, anger, and pain naturally lead to a single question: Who will be held accountable for this?

Yet the response from senior Hong Kong officials has been deeply disappointing.

A Government That “Cannot Be Wrong”

The Hong Kong government’s first reaction was astonishing: it blamed the fire on the use of bamboo scaffolding and immediately pushed for legislation to ban bamboo scaffolds. Without proper investigation, the government casually pinned the problem on bamboo, leaving the public with the impression that officials were merely searching for a “not us” excuse—an attitude cold and indifferent to human life.

Yet the footage showed the opposite. The falling bamboo poles were not on fire; instead, flames raced along the sheets of netting wrapped around the buildings. The blame placed on bamboo looked like a crude attempt to deflect responsibility.

When it was later suggested that non-compliant, flammable netting was the real reason the fire spread so quickly, the relevant bureau chief hastily declared that the materials had “been verified as compliant,” prompting widespread disbelief. Those who questioned the government were then accused of “inciting hatred” or being “troublemakers”—a clear reflection of the post-2019 logic in Hong Kong: the government is always right, and anyone who questions it is subversive.

While the entire city was gripped by shock and grief, authorities chose repression over empathy, acting as if heavy-handed tactics could simply bury public anger. This showed a profound misunderstanding of Hong Kong’s unique social fabric and international context. With the world watching, expecting Hongkongers to react like citizens long conditioned under an authoritarian regime in the mainland revealed a startling lack of political awareness.

As a result, Hongkongers across the globe—supported by international media—laid bare the deeper societal, structural, and governance failures behind the fire.

A Government Accountable to the People

Democratic governments may be inefficient or inconsistent, but those that ignore their people for too long ultimately get voted out. Thus they at least claim accountability. In disasters, the most essential response is empathy and acknowledgment of public concerns—not suppression or demands for silence.

The Hong Kong fire has drawn global attention, causing many to suddenly re-examine the skyscrapers built worldwide over recent decades. No matter the country, these massive structures can become sources of catastrophe. I still remember watching Paul Newman’s 1974 classic The Towering Inferno, a film built around fears of high-rise disasters: a 138-storey skyscraper becomes an inferno during its opening ceremony because of cost-cutting and substandard safety systems. The film’s message was clear—human arrogance and greed can turn innovation into tragedy.

Hong Kong’s dense population means high-rise living is long normalized; Australian cities like Melbourne and Sydney have similarly embraced this lifestyle. But have we truly learned how to live safely in such environments? The fire at Hong Fuk Court—and similar tragedies like London’s 2017 Grenfell Tower fire—are harsh lessons for modern societies on managing high-density urban living.

The Hong Kong fire demonstrates clearly that the city—including its government—has not yet learned to manage such buildings safely. When officials treat victims’ questions as threats to national security, it shows an unwillingness to confront reality.

China’s rapid urbanization means cities across the mainland now resemble Hong Kong, sharing similar latent risks. Ensuring these skyscrapers are safe homes is also a pressing concern for the central government. I do not believe Beijing will ignore the lessons of this Hong Kong disaster or use “national security” as an excuse to bury the underlying problems; that would not benefit China either.

Recent developments suggest the central government may pursue accountability among Hong Kong officials. Perhaps, amid all the suffering, this is one small glimmer of hope for Hongkongers.

On 26 November 2025, a massive fire broke out at Wang Fuk Court in Tai Po, Hong Kong, during exterior wall renovation. Flames raced along the scaffolding and netting, igniting seven residential blocks at once. The blaze spread from one building to the entire estate in minutes. As of 2 December, the disaster had left 156 people dead and more than 30 missing, making it one of the deadliest residential fires in decades worldwide.

Caught between grief and fury, the public cannot help but ask:

Was this an accident, or a tragedy created by systemic failure?

A Disaster Rooted in Sheer Complacency

First-hand footage circulating online shows how quickly the fire spread. The primary cause was the use of non–fire-retardant scaffolding netting and foam panels. Under the Buildings Department and Labour Department’s guidelines, netting must be flame-retardant and self-extinguish within three seconds of ignition. But the netting seen on-site shot up in flames immediately.

Investigations revealed an even more infuriating detail:

Some contractors did purchase compliant fire-retardant netting — but installed it only at the base of each building, replacing the rest with ordinary, non-compliant netting to save roughly HKD 20,000 (about 105,800 TWD). Additionally, foam boards were used to seal some unit windows, funneling flames directly into homes. These materials had long been prohibited, yet were still used simply because they were cheap.

What’s worse, this danger was no secret.

For years, watchdog groups warned the government about flammable netting. Since 2023, Civic Sight chairman Michael Poon had sent over 80 emails to authorities about unsafe scaffolding in various housing estates. In May 2025, he specifically named Wang Fuk Court as using suspiciously non-compliant netting — but letters to the Fire Services Department never received a formal reply.

Residents also lodged complaints to multiple departments, only to be told that officials had “checked the certificates” or that fire risks were “low,” with no further action taken.

Engineers note that government inspections focus mainly on whether the structure of the scaffolding is secure, not whether the materials are fire resistant — effectively outsourcing public safety to the industry’s “self-discipline.” With lax oversight, contractors adopted a “no one checks anyway” mindset that turned regulations into empty words.

Inside the fire zone, fire safety systems also failed. Automatic alarms, sprinklers, hydrants, and fire bells in the eight buildings were all found to be nonfunctional, depriving residents of early escape warnings. Some exits were clogged with debris. It took three and a half hours from the first report for the incident to be upgraded to a five-alarm fire — a delay that worsened casualties.

From flammable materials, to inadequate government oversight, to malfunctioning fire systems, every layer of failure stacked together.

Let’s be clear: This was a man-made disaster.

Who Bears Responsibility?

If this was a man-made tragedy, where exactly did the system fail?

Police have arrested 15 people on suspicion of manslaughter, including executives from the main contractor, consulting engineers, and subcontractors involved in scaffolding and façade work.

The incident has also sparked another controversy:

Were there political–business entanglements?

DAB Tai Po South district councilor Wong Pik-kiu served as an adviser to the Wang Fuk Court owners’ corporation from early 2024 to 2025. During her tenure, the corporation approved the renovation project. She allegedly lobbied owners door-to-door to support the works and pushed for multiple controversial decisions, including simultaneous works on multiple blocks — increasing both risk and cost.

A district councilor serving as an OC adviser is a highly sensitive overlap. Councillors are expected to act as neutral third parties safeguarding public interest, whereas OC advisers handle tenders, project monitoring, and major financial decisions. The dual role naturally raises questions of conflict of interest.

Whether the OC, councilor, and contractors engaged in collusion, dereliction of duty, or even corruption remains under investigation by the ICAC and police.

But the tragedy exposes deep structural issues in Hong Kong’s building management system, which is a clear warning sign for the OC mechanism.

The Wider Problem: Aging Buildings and Weak Oversight

Old-building maintenance is a territory-wide problem. Wang Fuk Court is not an isolated case.

In 2021, Hong Kong had 27,000 buildings over 30 years old. By 2046, the number will rise to 40,000. With aging buildings, major repairs, fire system upgrades, escape-route improvements, and structural checks are becoming increasingly urgent.

But most homeowners lack engineering knowledge and rely entirely on their owners’ corporations. OC committee members are volunteers with limited time and expertise. Under pressure from mandatory inspection deadlines, they often make poor decisions with incomplete information.

Meanwhile, OCs hold enormous power — they manage all repair funds and approve all works — yet face minimal oversight. Bid-rigging and collusion are widespread.

Classic tactics involve competitors privately agreeing who should “win” a tender, distorting competition and harming owners.

Although Wang Fuk Court’s repair fund was managed by the OC, the Housing Bureau — overseer of subsidized housing — also cannot escape blame. With massive project costs and questionable workmanship, why did authorities not intervene or conduct deeper audits?

These systemic gaps enable problems to repeat endlessly.

How Australia Handles Major Repairs and Tendering

In contrast to Hong Kong’s volunteer-run OC model, Australia’s strata property system uses professional management + statutory regulation.

Owners corporations hire licensed strata managers, who then appoint independent building consultants to assess required works. Tendering follows a transparent, standardized process that includes checking contractor licences, insurance, and track records.

Owners rarely deal directly with contractors, reducing information asymmetry and the risk of lobbying. Major expenses must be approved by the owners’ meeting, and strata managers must provide written reports and bear legal accountability.

This creates clear divisions of responsibility, heightens transparency, and minimizes corruption, bid-rigging, and low-quality work. Contractors have fewer opportunities to privately lobby homeowners or manipulate the tendering process.

Is the Government Truly Responding to Public Demands?

After the disaster was widely recognized as man-made, public anger exploded.

Residents, experts, scholars, and former officials all condemned the failure of Hong Kong’s regulatory system and demanded accountability.

Residents quickly formed the Tai Po Wang Fuk Court Fire Concern Group, raising four demands on 28 November:

-

Ensure proper rehousing for affected residents

-

Establish an independent commission of inquiry

-

Conduct a comprehensive review of major-repairs regulations

-

Hold departments accountable for oversight failures

Over 5,000 online signatures were collected the next day.

Under intense public pressure, Chief Executive John Lee announced on 3 December the formation of an “independent committee” led by a judge to examine the fire and its rapid spread.

However — and this is crucial — this body is not a statutory Commission of Inquiry.

A COI, established under the Commissions of Inquiry Ordinance, has legal powers to summon witnesses, demand documents, and take sworn testimony, giving it far stronger investigative and accountability capabilities.

By comparison, the “independent committee” lacks compulsory powers and focuses on “review and prevention” rather than defining responsibility or recommending disciplinary action.

This falls far short of public expectations, raising doubts about whether the government genuinely intends to confront the issue.

A Second Fire: The Fire of Distrust

In the aftermath of the Wang Fuk Court inferno, the community displayed remarkable self-organisation: residents gathered supplies, assisted displaced families, compiled lists of elderly neighbours, and coordinated temporary support. These actions were the natural response of civil society stepping in when public governance collapses. And while contractor negligence and construction issues sparked public outrage, an even deeper anger targeted the government’s total failure in oversight and crisis management.

Ironically, as residents were busy helping one another, some volunteers were arrested on suspicion of “incitement.” The fire broke out just days before the 7 December Legislative Council election. In the eyes of the government, any form of spontaneous community mobilisation seemed to be viewed as a “risk” rather than support.

Haunted by the shadow of 2019, the authorities remain terrified of bottom-up community organising. Instead of crisis management, they engage in risk suppression—focusing on dampening social sentiment rather than improving rescue efficiency. Blame is shifted toward “those who raise questions,” instead of the systems that produced the problem in the first place.

These reactions transformed what could have been a moment of community unity into a much deeper crisis of public trust.

Beijing’s Disaster Narrative

In sharp contrast to the Hong Kong government’s understated approach, Beijing intervened swiftly and publicly. President Xi Jinping ordered full rescue efforts and expressed condolences immediately. Yet such speed also suggests that Beijing vividly remembers the 2022 Urumqi fire, which triggered the “White Paper Movement.”

In Chinese political logic, fires are never just accidents—they can become flashpoints of public anger. With long-standing grievances over housing policy, old-building safety, and the culture of unaccountability, Beijing moved quickly to prevent emotions from spilling over.

Notably, the Office for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong issued a statement during the rescue phase, warning that “anti-China, destabilising forces are waiting to create chaos,” emphasising that political stability overrides everything else.

Under China’s crisis-management style, officials frequently shift public focus from “the causes and responsibility of the disaster” toward “the hardship and heroism of rescue workers.” Following the Wang Fuk Court fire, some local media began flooding the airwaves with stories of brave firefighters and tireless medical staff, all being positive narratives that subtly eclipse the underlying issues of flammable materials, broken systems, and weak oversight.

By swiftly arresting a few contractors and engineers, authorities aim to frame the incident as the fault of several “technical offenders,” preventing accountability from extending to systemic failures or government departments.

This narrative reframes a man-made tragedy into a supposed showcase of “government mobilisation,” diluting public scrutiny and preventing grief and anger from evolving into collective resistance.

A particularly important detail:

In the early stages, several Western media outlets focused heavily on the idea that “bamboo scaffolding is inherently risky,” while barely discussing the scaffolding netting, material quality, or regulatory negligence. This inadvertently echoed the Hong Kong government’s early narrative frame. It also exposed a cultural bias—an assumption that bamboo equals danger—overlooking the rigorous safety standards of Hong Kong’s traditional scaffolding industry. As a result, some international reporting unintentionally helped divert attention away from structural, institutional failures during the crucial first days.

Who Should Be Held Accountable?

The shock of this catastrophe lies not only in the scale of casualties but in the fact that behind what seems like an “accident” are layers of systemic failure—from flammable netting and dead fire-safety systems, to weak regulation, chaotic building management, bid-rigging culture, and the government’s post-disaster reliance on a national-security framework to manage public sentiment.

So, the fundamental question remains:

Who is responsible for this fire?

As of the copy deadline (3 December) and after the seven-day mourning period, Hong Kong has seen zero officials, zero government departments, and zero senior leaders take any responsibility. Whether this was an accident or a man-made disaster is beyond obvious, yet the government—obsessed with saving face—refuses to admit regulatory failure. Instead, it blames bamboo and a handful of contractors, shrinking a deeply interconnected man-made catastrophe into the fault of a few convenient scapegoats.

AFP put it bluntly when a reporter asked Chief Executive John Lee:

“You said you want to lead Hong Kong from stability to prosperity.

But in this ‘prosperous’ society you described, 151 people have died in a single fire.

Why do you still deserve to keep your job?”

From 2019, to the pandemic, to the collapse of the medical system, and now this fire—no one has ever been held accountable for catastrophic policy failures.

What Can We Do?

The disaster is far from over. The real challenges are only beginning: nearly 2,000 households across the eight blocks face long-term displacement, trauma, and the struggle to rebuild their lives.

For Hongkongers and Chinese people living in Australia, what can be done?

Perhaps the answer is simpler—and more important—than we think:

Support those affected. Emotionally, psychologically, and materially. Even from afar, offering solidarity, sharing information, donating to practical assistance, or simply staying engaged with the issue matters.

After a tragedy like this, our role is not only to mourn.

It is to refuse to let the disaster fade away without accountability or reform.

And it is to remind ourselves, gently but urgently:

cherish the people beside us, and hold close those who still walk this uncertain world with us.

Listen Now

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

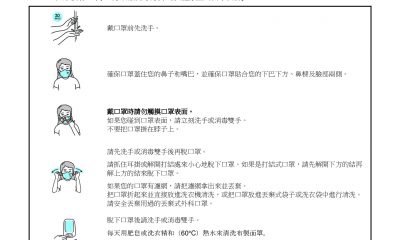

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單