Features

Australia in the Changing Generations (2) – Australian Identity

Published

7 months agoon

Anglo-Saxon culture to Diversity

Australian society began in the colonial era, with colonists not only from Britain, but also from other European countries to a lesser extent. However, the British naval presence in 1788 made these colonies the property of the British Crown, and they remain so to this day. Before the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, there were many Chinese settlers in Australia due to the Gold Rush. However, after the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia, the first immigration law was passed, requiring immigrants to pass an English language proficiency test, which opened up Australia to a predominantly British society. Australia then implemented the White Australia Policy. However, this policy was not based on skin color and race, but on language. Therefore, the discriminatory ethnic groups in Australian society at that time also included white Europeans who did not speak English. With the development of the society, Europeans who were culturally close to Britain but did not speak English, such as Greeks and Italians, were also accepted. These European immigrants lived in close proximity to the British culture, and it was not difficult for the second generation to integrate into the mainstream society, thus building the foundation of today’s white-dominated but respectful multicultural society in Australia.

As a result of the white Australia policy, Chinese and Pacific Islanders who originally spoke Chinese were excluded from Australia, resulting in Australia becoming a virtually British society before 1975. However, after the Second World War, due to the post-war reconstruction of Europe, immigrants from Europe gradually decreased, and with the British colonies around the world became independent, the number of young people from these emerging countries studying in Australia and immigrants increased. The Commonwealth’s Colombo Plan allowed African and Asian English speakers to stay in Australia, and the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 removed race as a factor in the selection of migrants.

Asian immigration increased in the 1980s, and today there are more Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, Nepalese and other Asian immigrants than there are traditional Greek, Italian or Eastern European immigrants, making Australia the most multicultural country in the world.

How Australians see themselves

Before the 1980s, when Australia’s population was not growing at a high rate each year, Australians did not have many opportunities to meet people of different ethnicities at school or in the community. As a result, older Australians nowadays, although accepting multiculturalism, seldom participate in community activities of different races and cultures. For them, they live in an English-speaking society with Western values, and their concerns are about Australia, the UK or the US and European world. Many of them are now in leadership or senior management positions in the society and community. They recognize that Australian society is not the same as it was when they were young, but they have little exposure to or understanding of multiculturalism.

Those who were born and grew up around the 1980s had the opportunity to meet immigrants from different parts of the world during their school years. Their interpersonal or social networks also include different ethnic groups, so most of them are open to multiculturalism, and they occasionally come into contact with and connect with it in their lives. However, they may not necessarily be enthusiastic about multiculturalism or hold a positive or valuing attitude towards it. As the society is moving towards accepting and respecting multiculturalism, they recognize that different ethnic groups should have the same opportunities to develop in the society, and they are willing to accept that different ethnic migrants are all Australians.

For those born after the 1990s, they have grown up in an Australia that is already quite diverse. They are also from a wide range of backgrounds, so they are more positive about diversity in Australia. They have a wide range of social networks and many of them have lived abroad, so they see Australia not necessarily as a British culture, but as a society that embraces cultural cohesion. This generation of Australians will play an important role in promoting the future development of a diverse Australia.

For these young people, Australian society is not an isolated continent, but can be connected to any country through the Internet. The social life around them provides them with opportunities to engage with the world. It is fair to say that they see Australia as a microcosm of the world, and Australians are uniquely placed to see themselves as living amongst the different peoples of the world.

Chinese immigrants after the 1990s

There were not a lot of Chinese immigrants to Australia before the 1980s as a large community as in today. These early migrants are now old and mostly retired. Their life experience in Australia and their English proficiency determines their different paths in integration. For those who did not speak English, many of them have lived in the Chinese community in Chinatown. For those who can communicate well in English, many of them are professionals and most of them will integrate into mainstream society. However, the Chinese who settled in Australia in the 1990s due to the June 4 Incident or the 1997 return of Hong Kong, because of their large numbers, lived in selected suburbs and formed large regional economic communities. Today, they are still very active in the society and have great social influence.

For them, they recognize Australia as a place to live and work, but at the same time they feel that culturally they have retained their Chinese values and customs. They recognize that they are part of the Australian community, but at the same time they see themselves as different from other Australians. They like freedom and democracy, but at the same time they think that China can achieve economic success in an authoritarian society, so they are not enthusiastic or supportive of the democratization of Chinese society or the freedom of the Chinese people. It can be said that they actually enjoy the freedom and democracy that they have in Australia, but they also believe that the totalitarianism in China can also bring about economic take-off and strength. Such contradictory values exist in many middle-aged and older Chinese immigrants, reflecting their pride in being Australian, but at the same time valuing their identity as Chinese.

Chinese immigrants who came to Australia in the last decade or so, on the contrary, are more sure of themselves as Australians and do not emphasize their Chinese cultural background. Perhaps it is because these immigrants, whether they grew up in Hong Kong or China, are certain that they are Hong Kong people, or grew up in China in contact with the foreign world, and do not necessarily accept the totalitarian rule of Communist China.

Engaging in Australian society

From the above observations, Chinese immigrants who came to Australia in different generations, due to the changes in Australian society and China’s entry into the world stage, their attitudes towards their identity as Australians and towards China are very different. As a result, the Chinese community has gradually split into different parts, and there is not much contact among the different communities as there is space for each.

This is also the case with other immigrant groups.

However, these differences do not affect their need to integrate into the community, but they all follow different trajectories to become part of Australian society. In this process, we can see that the Australian government has seldom taken the initiative to reach out, understand or intervene. Therefore, the various life and social problems encountered by the Chinese in these communities have long been ignored by the community, and the government has failed to deal with them proactively.

The Scanlon Foundation, which studies social cohesion in Australia, has pointed out that it is not easy for Chinese immigrants to integrate into the community, and this has become a social concern. We will continue to explore these issues in the next issue.

Mr. Raymond Chow, Publisher of Sameway Magazine

You may like

Features

The Limits of Capitalism: Why Can One Person Be as Rich as a Nation?

Published

4 days agoon

November 24, 2025

On November 6, Tesla’s shareholder meeting passed a globally shocking resolution: with more than 75% approval, it agreed to grant CEO Elon Musk a compensation package worth nearly one trillion US dollars.

According to the agreement, if he can achieve a series of ambitious operational and financial targets in the next ten years— including building a fleet of one million autonomous robotaxis, successfully selling one million humanoid robots, generating up to USD 400 billion in core profit, and ultimately raising Tesla’s market value from about USD 1.4 trillion to USD 8.5 trillion— his shareholding will increase from the current 13% to 25%. When that happens, Musk will not only have firmer control over the company, but may also become the world’s first “trillion-dollar billionaire.”

To many, this is a jaw-dropping number and a reflection of our era: while some people struggle to afford rent with their monthly salary, another kind of “worker” gains the most expensive “wage” in human history through intelligence, boldness, and market faith.

But this raises a question: on what grounds does Musk deserve such compensation? How is his “labor” different from that of ordinary people? How should we understand this capitalist reward logic and its social cost?

Is One Trillion Dollars Reasonable? Why Are Shareholders Willing to Give Him a Trillion?

A trillion-dollar compensation is almost unimaginable to most people. It equals the entire annual GDP of Poland (population 36 million in 2024), or one-quarter of Japan’s GDP. For a single person’s labor to receive this level of reward is truly beyond reality.

Musk indeed has ability, innovative thinking, and has built world-changing products— these contributions cannot be denied. But is he really worth a trillion dollars?

If viewed purely as “labor compensation,” this number makes no sense. But under capitalist logic, it becomes reasonable. For Tesla shareholders, the meaning behind this compensation is far more important than the number itself.

Since Musk invested his personal wealth into Tesla in 2004, he has, within just over a decade, led the company from a “money-burning EV startup” into the world’s most valuable automaker, with market value once exceeding USD 1.4 trillion. He is not only a CEO but a combination of “super engineer” and brand evangelist, directly taking part in product design and intervening in production lines.

Furthermore, Musk’s current influence and political clout make him irreplaceable in Tesla’s AI and autonomous-driving decisions. If he left, the company’s AI strategy and self-driving vision would likely suffer major setbacks. Thus, shareholders value not just his labor, but his ability to steer Tesla’s long-term strategy, brand, and market confidence.

Economically, the enormous award is considered a “high-risk incentive.” Chair Robyn Denholm stated that this performance-based compensation aims to retain and motivate Musk for at least seven and a half more years. Its core logic is: the value of a leader is not in working hours, but in how much they can increase a company’s value, and whether their influence can convert into long-term competitive power. It is, essentially, the result of a “shared greed” under capitalism.

Musk’s Compensation Game

In 2018, Musk introduced a highly controversial performance-based compensation plan. Tesla adopted an extreme “pay-for-results” model for its CEO: he received no fixed salary and no cash bonus. All compensation would vest only if specific goals were met. This approach was unprecedented in corporate governance— tightly tying pay to long-term performance and pushing compensation logic to an extreme.

Musk proposed a package exceeding USD 50 billion at that time. In 2023, he already met all 12 milestones of the 2018 plan, but in early 2024 the Delaware Court of Chancery invalidated it, citing unfair negotiation and lack of board independence. The lawsuit remains ongoing.

A person confident enough to name such an astronomical reward for themselves is almost unheard of. Rather than a salary, Musk essentially signed a bet with shareholders: if he raises Tesla’s valuation from USD 1.4 trillion to USD 8.5 trillion, he earns stock worth hundreds of billions; if he fails, the options are worthless.

For Musk, money may be secondary. What truly matters is securing control and decision-making power, allowing him greater influence within Tesla and across the world. In other words, this compensation is an investment in his long-term influence, not just payment for work.

The Forgotten Workers, Users, and Public Interest

Yet while Tesla pursues astronomical valuation and massive executive compensation, a neglected question emerges: does the company still remember who it serves?

In business, companies prioritize influence, market share, revenue, and growth— the basics of survival and expansion. But corporate profit comes not only from risk-taking investors or visionary leaders; it also relies on workers who labor, consumers who pay, and public systems that allow them to operate.

If these foundations are ignored, lofty visions become towers without roots.

Countless workers worldwide—including Tesla’s own factory workers—spend the same hours and life energy working. Many work 60–70 hours a week, some exceeding 100, bearing physical and mental stress. Yet they never receive wealth, status, or social reward proportionate to their labor.

More ironically, Tesla’s push for automation, faster production, and cost-cutting has brought recurring overwork and workplace injuries. Workers bear the cost of efficiency, but the applause and soaring market value often go only to executives and shareholders.

How then do these workers feel when a leader may receive nearly a trillion dollars from rising share prices?

How Systems Allow Super-Rich Individuals to Exist

To understand how Musk accumulates such wealth, one must consider institutional structures. Different political systems allow vastly different levels of personal wealth.

In authoritarian or communist systems, no matter how capable business elites are, power and assets ultimately belong to the state. In China, even giants like Alibaba and Tencent can be abruptly restructured or restricted, with the state taking stakes or exerting control. Corporate and personal wealth never fully stand independent of state power.

The U.S., by contrast, is the opposite: the government does not interfere with how rich you can become. Its role is to maintain competition, letting the market judge.

Historically, the U.S. government broke up giants like Standard Oil and AT&T— not to suppress personal wealth, but to prevent monopolies. In other words, the U.S. system doesn’t stop anyone from becoming extremely rich; it only stops them from destroying competition.

This makes the Musk phenomenon possible: as long as the market approves, one person may amass nation-level wealth.

Rewriting Democratic Systems

And Musk may be only the beginning. Oxfam predicts five more trillion-dollar billionaires may emerge in the next decade. They will wield power across technology, media, diplomacy, and politics— weakening governments’ ability to restrain them and forcing democracies to confront the challenge of “individual power surpassing institutions.”

Musk is the clearest example. In the 2024 U.S. election, he provided massive funding to Trump, becoming a key force shaping the campaign. He has repeatedly influenced politics in Europe and Latin America, and through his social platform and satellite network has shaped political dynamics. In the Ukraine war and Israel–Palestine conflict, his business decisions directly affected frontline communications.

When tech billionaires can determine elections or sway public opinion, democracy still exists— but increasingly with conditions attached.

Thus, trillion-dollar billionaires represent not only wealth inequality but a coming stress test for democracy and rule of law. When one person’s market power can influence technology, defense, and global order, they wield a force capable of challenging national sovereignty.

When individual market power affects public interest, should governments intervene? Should institutions redraw boundaries?

The Risk of Technological Centralization

When innovation, risk, and governance become concentrated in a few individuals, technology may advance rapidly, but society becomes more fragile.

Technology, once seen as a tool of liberation, risks becoming the extended will of a single leader— if AI infrastructure, energy networks, global communication systems, and even space infrastructure all fall under the power radius of a few tech giants.

This concentration reshapes the “publicness” of technology. Platforms, AI models, satellite networks, VR spaces— once imagined as public squares— are owned not by democratic institutions but private corporations. Technology once promised equality, yet now information is reshaped by algorithms, speech is amplified by wealth, and value systems are defined by a few billionaires.

Can These Goals Even Be Achieved?

Despite everything, major uncertainties remain. Tesla’s business spans EVs, AI, autonomous-driving software, humanoid robots, and energy technology. Every division— production, supply chain, AI, battery tech— must grow simultaneously; if any part fails, the plan collapses.

Market demand is also uncertain. One million robotaxis and one million humanoid robots face technological, regulatory, and consumer barriers.

Global factors matter too: shareholder and market confidence rely on stable supply chains. China is crucial to Tesla’s production and supply, increasing external risk and political exposure. Recent U.S.–China tensions, tariffs, and import policies directly affect Tesla’s pricing and supply strategy. Tesla has reportedly increased North American sourcing and asked suppliers to remove China-made components from U.S.–built vehicles— but the impact remains unclear.

If all goes well, Tesla’s valuation will rise from USD 1.4 trillion to 8.5 trillion, surpassing the combined market value of the world’s largest tech companies. But even without achieving the full target, shareholders may still benefit from Musk’s leadership and value creation.

To age with security and dignity is a right every older person deserves, and a responsibility society—especially the government—must not shirk.

I have been writing the column “Seeing the World Through Australia’s Eyes”, and it often makes me reflect: as a Hong Kong immigrant who has lived in Australia for more than 30 years, I am no longer the “Hong Kong person” who grew up there, nor am I a newly arrived migrant fresh off the plane. I am now a true Australian. When viewing social issues, my thinking framework no longer comes solely from my Hong Kong upbringing, but is shaped by decades of observation and experience in Australia. Of course, compared with people born and raised here, my perspectives are still quite different.

This issue of Fellow Travellers discusses the major transformation in Australia’s aged care policy. In my article, I pointed out that this is a rights-based policy reform. For many Hong Kong friends, the idea that “older people have rights” may feel unfamiliar. In traditional Hong Kong thinking, many older people still need to fend for themselves after ageing, because the entire social security system lacks structured provisions for the elderly. Most Hong Kong older adults accept the traditional Chinese belief of “raising children to support you in old age”, expecting the next generation to provide financial and daily-life support. This mindset is almost impossible to find in mainstream Australian society.

Therefore, when Australia formulates aged care policy, it is built upon a shared civic value: to age with support and dignity is a right every older adult should enjoy, and a responsibility society—especially the government—must bear. As immigrants, we may choose not to exercise these rights, but we should instead ask: when society grants every older person these rights, why should our parents and elders deprive themselves of using them?

I remember that when my parents first came to Australia, they genuinely felt it was paradise: the government provided pensions and subsidised independent living units for seniors. Their quality of life was far better than in Hong Kong. Later they lived in an independent living unit within a retirement village, and only needed to use a portion of their pension to enjoy well-rounded living and support services. There were dozens of Chinese residents in the village, which greatly expanded their social circle. My parents were easily content; to them, Australian society already provided far more dignity and security than they had ever expected. My mother was especially grateful to the Rudd government at that time for allowing them to receive a full pension for the first time.

However, when my parents eventually needed to move into an aged care facility for higher-level care, problems emerged: Chinese facilities offering Cantonese services had waiting lists of several years, making it nearly impossible to secure a place. They ended up in a mainstream English-speaking facility connected to their retirement village, and the language barrier immediately became their biggest source of suffering. Only a few staff could speak some Cantonese, so my parents could express their needs only when those staff were on shift. At other times, they had to rely on gestures and guesses, leading to constant misunderstandings. Worse still, due to mobility issues, they were confined inside the facility all day, surrounded entirely by English-speaking residents and staff. They felt as if they were “softly detained”, cut off from the outside world, with their social life completely erased.

After my father passed away, my mother lived alone, and we watched helplessly as she rapidly lost the ability and willingness to communicate with others. Apart from family visits or church friends, she had almost no chance to speak her mother tongue or have heartfelt conversations. Think about it: we assume receiving care is the most important thing, but for older adults who do not speak English, being forced into an all-English environment is equivalent to losing their most basic right to human connection and social participation.

This personal experience shocked me, and over ten years ago I became convinced that providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care—including services in older people’ mother tongues—is absolutely necessary and urgent for migrants from non-English backgrounds. Research also shows that even migrants who speak fluent English today may lose their English ability if they develop cognitive impairment later in life, reverting to their mother tongue. As human lifespans grow longer, even if we live comfortably in English now, who can guarantee we won’t one day find ourselves stranded on a “language island”?

Therefore, I believe the Chinese community has both the responsibility and the need to actively advocate for the construction of more aged care facilities that reflect Chinese culture and provide services in Chinese—especially Cantonese. This is not only for our parents, but possibly for ourselves in the future. The current aged care reforms in Australia are elevating “culturally and linguistically appropriate services” to the level of fundamental rights for all older adults. I see this as a major step forward and one that deserves recognition and support.

I remember when my parents entered aged care, they requested to have Chinese meals for all three daily meals. I patiently explained that Australian facilities typically serve Western food and cannot be expected to provide daily Chinese meals for individual residents—at most, meals could occasionally be ordered from a Chinese restaurant, but they might not meet the facility’s nutrition standards. Under today’s new legislation, what my parents once requested has now become a formal right that society must strive to meet.

I have found that many Chinese older adults actually do not have high demands. They are not asking for special treatment—only for the basic rights society grants every older person. But for many migrants, even knowing what rights they have is already difficult. As first-generation immigrants, our concerns should go beyond careers, property ownership and children’s education; we must also devote time to understanding our parents’ needs in their later years and the rights this society grants them.

I wholeheartedly support Australia’s current aged care reforms, though I know there are many practical details that must still be implemented. I hope the Chinese community can seize this opportunity to actively fight for the rights our elders deserve. If we do not speak up for them, then the more unfamiliar they are with Australia’s system, the less they will know what they can—and should—claim.

In the process of advocating for culturally suitable aged care facilities for Chinese seniors, I discovered that our challenges come from our own lack of awareness about the rights we can claim. In past years, when I saw the Andrews Labor Government proactively expressing willingness to support Chinese older adults, I believed this goodwill would turn smoothly into action. Yet throughout the process, what I saw instead was bureaucratic avoidance and a lack of understanding of seniors’ real needs.

For example, land purchased in Templestowe Lower in 2021 and in Springvale in 2017 has been left idle by the Victorian Government for years. For the officials responsible, shelving the land has no personal consequence, but in reality it affects whether nearly 200 older adults can receive culturally appropriate care. If we count from 2017, and assume each resident stays in aged care for two to three years on average, we are talking about the wellbeing of more than a thousand older adults.

Why has the Victorian Government left these sites unused and refused to hand them to Chinese community organisations to build dedicated aged care facilities? It is baffling. Since last November, these officials—even without consulting the Chinese community—have shifted the land use application toward mainstream aged care providers. Does this imply they believe mainstream providers can better meet the needs than Chinese community organisations? I believe this is a serious issue the Victorian Government must reflect upon. Culturally appropriate aged care is not only about basic care, but also about language, food and social dignity. Without a community-based perspective, these policy shifts risk deepening immigrant seniors’ sense of isolation, rather than fulfilling the rights-based vision behind the reforms.

Raymond Chow

Features

Rights-Based Approach – Australia’s Aged Care Reform

Published

4 days agoon

November 24, 2025

The Australian government has in recent years aggressively pushed forward aged care reform, including the new Aged Care Act, described as a “once-in-a-generation reform.” Originally scheduled to take effect in July 2025, it was delayed by four months and officially came into force on November 1.

Elderly Rights Enter the Agenda

The scale of the reform is significant, with the government investing an additional AUD 5.6 billion over five years. Australia’s previous aged care system was essentially based on government and service providers allocating resources, leaving older people to passively receive care. Service quality was inconsistent, and at one point residential aged care facilities were exposed for “neglect, abuse, and poor food quality.” The reform rewrites the fundamental philosophy of the system, shifting from a provider-centred model to one in which older people are rights-holders, rather than passive recipients of charity.

The new Act lists, for the first time, the statutory rights of older people, including autonomy in decision-making, dignity, safety, culturally sensitive care, and transparency of information. In other words, older people are no longer merely service recipients, but participants with rights, able to make requests and challenge services.

Many Chinese migrants who moved to Australia before or after retirement arrived through their children who had already migrated, or settled in Australia in their forties or fifties through skilled or business investment visas. Compared with Hong Kong or other regions, Australia’s aged care services are considered relatively good. Regardless of personal assets, the government covers living expenses, medical care, home care and community activities. Compared with their country of origin, many elderly people feel they are living in an ideal place. Of course, cultural and language differences can cause frustration and inconvenience, but this is often seen as part of the cost of migration.

However, this reform requires the Australian government to take cultural needs into account when delivering aged care services, which represents major progress. The Act establishes a Statement of Rights, specifying that older people have the right to receive care appropriate to their cultural background and to communicate in their preferred language. For Chinese-Australian older people, this is a breakthrough.

Therefore, providing linguistically and culturally appropriate care—such as Chinese-style meals—is no longer merely a reasonable request but a right. Similarly, offering activities such as mahjong in residential care for Chinese elders is considered appropriate.

If care facility staff are unable to provide services in Chinese, the government has a responsibility to set standards, ensuring a proportion of care workers can communicate with older people who do not speak English, or provide support in service delivery. When language barriers prevent aged care residents from having normal social interaction, it constitutes a restriction on their rights and clearly affects their physical and mental health.

A New Financial Model: Means Testing and Co-Payment

Another core focus of the reform is responding to future financial and demographic pressures. Australia’s population aged over 85 is expected to double in the next 20 years, driving a surge in aged care demand. To address this, the government introduced the Support at Home program, consolidating previous home care systems to enable older people to remain at home earlier and for longer. All aged care providers are now placed under a stricter registration and regulatory framework, including mandatory quality standards, transparency reporting and stronger accountability mechanisms.

Alongside the reform, the most scrutinised change is the introduction of a co-payment system and means testing. With the rapidly ageing population, the previous model—where the government bore most costs—is no longer financially sustainable. The new system therefore requires older people with the capacity to pay to contribute to the cost of their care based on income and assets.

For home-based and residential care, non-clinical services such as cleaning, meal preparation and daily living support will incur different levels of co-payment according to financial capacity. For example, low-income pensioners will continue to be primarily supported by the government, while middle-income and asset-rich individuals will contribute proportionally under a shared-funding model. To prevent excessive burden, the government has introduced a lifetime expenditure cap, ensuring out-of-pocket costs do not increase without limit.

However, co-payment has generated considerable public debate. First, the majority of older Australians’ assets are tied to their homes—over 76% own their residence. Although this appears as high asset value, limited cash flow may create financial pressure. There are also concerns that co-payment may cause some families to “delay using services,” undermining the reform’s goal of improving care quality.

Industry leaders also worry that wealthier older people who can afford large refundable accommodation deposits (RADs) may be prioritised by facilities, while those with fewer resources and reliant on subsidies may be placed at a disadvantage.

The Philosophy and Transformation of Australia’s Aged Care

Australia’s aged care policy has not always been centred on older people. Historically, with a young population and high migration, the demand for elder services was minimal, and government support remained supplementary. However, as the baby-boomer generation entered old age and medical advances extended life expectancy, older people became Australia’s fastest-growing demographic. This shift forced the government to reconsider the purpose of aged care.

For decades, the core policy principle has been to avoid a system where “those with resources do better, and those without fall further behind.” The essence of aged care has been to reduce inequality and ensure basic living standards—whether through pensions, public healthcare or government-funded long-term care. This philosophy remains, but rising financial pressure has led to increased emphasis on shared responsibility and sustainability.

Ageing Population Leads to Surging Demand and Stalled Supply

Beyond philosophy, Australia’s aged care system faces a reality: demand is rising rapidly while supply lags far behind. More than 87,000 approved older people are currently waiting for home-care packages, with some waiting up to 15 months. More than 100,000 additional applications are still pending approval. Clearly, the government lacks sufficient staffing to manage the increased workload created by reform. Many older people rely on family support while waiting, or are forced into residential care prematurely. Although wait times have shortened for some, the overall imbalance between supply and demand remains unresolved.

At the same time, longer life expectancy means residential aged care stays are longer, reducing bed turnover. Even with increased funding and new facilities, bed availability remains limited, failing to meet rising demand. This also increases pressure on family carers and drives demand for home-based services.

Differences Between Chinese and Australian Views on Ageing

In Australia, conversations about ageing often reflect cultural contrast. For many older migrants from Chinese backgrounds, the aged care system is unfamiliar and even contradictory to their upbringing. These differences have become more evident under the latest reform, shaping how migrant families interpret means testing and plan for later life.

In traditional Chinese thinking, ageing is primarily a personal responsibility, followed by family responsibility. In places like Hong Kong, older people generally rely on their savings, with a light tax system and limited government role. Support comes mainly in the form of small allowances, such as the Old Age Allowance, which is more of a consumption incentive than part of a care system. Those with serious needs are cared for by children; if children are unable, they may rely on social assistance or move somewhere with lower living costs. In short, the logic is: government supplements but does not lead; families care for themselves.

Australia’s thinking is entirely different. As a high-tax society, trust in welfare is based on a “social contract”: people pay high taxes in exchange for support when disabled, elderly or in hardship. This applies not only to older people but also to the NDIS, carer payments and childcare subsidies. Caring for vulnerable people is not viewed as solely a family obligation but a shared social responsibility. Australians discussing aged care rarely frame it around “filial duty,” but instead focus on service options, needs-based care and cost-sharing between the government and individuals.

Migrants Lack Understanding of the System

These cultural differences are especially evident among migrant families. Many elderly migrants have financial arrangements completely different from local Australians. Chinese parents often invested heavily in their children when young, expecting support later in life. However, upon arriving in Australia, they are often already elderly, lacking pension savings and unfamiliar with the system, and must rely on government pensions and aged care applications. In contrast, local Australians accumulate superannuation throughout their careers and, upon retirement, move into retirement villages or assisted living, investing in their own quality of life rather than relying on children.

Cultural misunderstanding can also lead migrant families to misinterpret the system. Some transfer assets to children early, assuming it will reduce assessable wealth and increase subsidies. However, in Australia, asset transfers are subject to a look-back period, and deeming rules count potential earnings even if money has been transferred. These arrangements may not provide benefits and may instead reduce financial security and complicate applications—what was thought to be a “smart move” becomes disadvantageous.

Conclusion

In facing the new aged care system, the government has a responsibility to communicate widely with migrant communities. Currently, reporting on the reform mainly appears in mainstream media, which many older migrants do not consume. As a result, many only have superficial awareness of the changes, without proper understanding. Without adequate community education, elderly migrants who do not speak English cannot possibly know what rights the law now grants them. If people are unaware of their rights, they naturally cannot assert them. With limited resources, failure to advocate results in neglect and greater inequality. It is time to make greater effort to understand how this era of reform will affect our older people.

Listen Now

Trump Holds Talks with Xi Jinping and Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Within 24 Hours

Research Shows Coalition Voter Trust Hits Record Low

Australia’s Emergency Mental Health Crisis Worsens

US Envoy Denies Bias as Sudan Ceasefire Push Faces Setbacks

UN Launches Selection Process for New Secretary-General, Growing Calls for a Female Leader

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Trump Accepts Invitation to Visit China in April Next Year

Pauline Hanson Sparks Controversy by Wearing Muslim Burqa in Parliament

Australia Housing Affordability Falls to Historic Lows

Bitcoin Plunge Sparks Market Panic

Europe Rushes Counterproposal to Reassert Ukraine at the Heart of Peace Talks

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

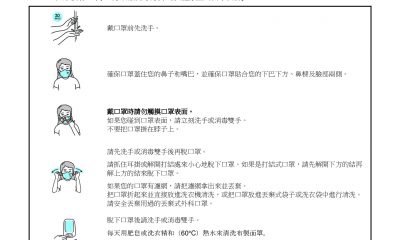

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單