Features

One Year Countdown: Support for Both Major Parties Declines – Where Is the 2026 Victorian Election Heading?

Published

2 months agoon

Victoria will hold its state election on 28 November 2026. Although the election is still about a year away, political dynamics are already shifting, and public discussion has heated up following the appointment of Jess Wilson as the new leader of the Victorian Liberal Party, adding new variables to what had been a relatively stable political landscape.

Meanwhile, the Labor Party still holds a majority of seats, but polls indicate that its support is not unshakable. Recent surveys show that Labor’s primary vote has declined slightly, currently hovering around 28% to 30%. By comparison, the Coalition’s primary support is about 36%, showing some catching-up momentum. More notably, support for independent candidates and minor parties is rising, with roughly 22% of voters indicating a willingness to cast their vote outside the two major parties. This reflects a declining trust in the major parties and a growing voter preference for new faces or non-traditional options.

However, the shifts in major party support are not without reason. For Victorians—especially within the rapidly growing multicultural communities—it may be time to reassess whether the two major parties have responded adequately to social change and the needs of new migrants over the past decade, in order to judge which political force best represents their interests and future.

Labor Party: In the Shadow of Andrews — Both an Asset and a Burden

In the past 35 years, the Victorian premiership has been held by Labor for 25 years, solidifying its dominant position in state politics. Former Premier Daniel Andrews served for 8 years and 9 months, and his achievements and controversies continue to strongly influence subsequent Labor governments.

During Andrews’ tenure, Victoria’s economy grew impressively, Melbourne expanded rapidly, and infrastructure projects were undertaken across the state. The most notable include the Suburban Rail Loop, West Gate Tunnel, Metro Tunnel, and large-scale level crossing removal projects. Most of these projects relied heavily on debt financing, increasing the fiscal burden, but also created tens of thousands of jobs and reinforced Victoria’s position as Australia’s most dynamic economy. Observers generally agree that Andrews’ period saw Victoria’s economy, infrastructure, and education sectors ranking among the nation’s best.

However, these “ambitious projects” have faced numerous problems during implementation. Construction proceeded recklessly despite insufficient funds and unconfirmed costs. Among them, the Suburban Rail Loop has been criticized as a massive waste of taxpayers’ money: from an initially estimated total cost of around AUD 50 billion, the construction costs for the first two stages have already soared to over AUD 216 billion, with the final expense still unknown.

At the same time, post-pandemic economic pressures, rising interest rates, rapidly expanding debt, budget deficits, along with multiple project delays and cost overruns, have carried over into the tenure of current Premier Jacinta Allan. Victoria’s economic growth has slowed in recent years, and housing prices have stagnated, lagging behind stronger recoveries in other states. This has left many citizens frustrated, and Labor’s polling has weakened as a result.

The recently opened Metro Tunnel has become the most symbolic achievement of the Victorian Labor government in recent years and could help refocus voters’ attention on Labor’s governance. Yet, facing the upcoming re-election challenge, Allan still faces significant hurdles: a severe fiscal situation, persistently high cost of living, rising crime rates, deep social and economic impacts post-pandemic, and general dissatisfaction from the business community.

With the state’s debt projected to climb to AUD 194 billion by 2029, Allan has indicated that infrastructure and housing policy will remain the core of her campaign strategy, meaning debt is likely to continue increasing.

On law-and-order issues, in response to rising youth crime rates, the Allan government recently introduced a new bill allowing 14-year-old violent offenders to be sentenced as adults, partially closing the Coalition’s space to attack Labor on crime policy.

Liberal Party: New Leader Needs More Prominent Policies

In recent years, the Coalition’s support among young voters and multicultural communities has steadily declined. The Liberal Party has long struggled with internal conflicts, leadership struggles, and sidelining of moderates. The appointment of a young female leader is widely seen as an attempt to revamp the party’s image and re-engage voters under 50.

Jess Wilson quickly unveiled an initial campaign blueprint after taking office, focusing on abolishing five major taxes to “ease the cost-of-living burden and restore state finances.” Her policy focus is centered on four main areas: state debt management, law-and-order, healthcare, and housing affordability. She also plans to introduce legislation to make coercive control a criminal offense under family violence law.

However, structurally, the path ahead is clearly difficult: Labor currently holds a majority in the lower house, and for the Coalition to flip the government, it would need to win at least 16 additional seats. Labor has won the past two elections by a wide margin, reinforcing the ruling party’s confidence and highlighting that for the Coalition to regain voter trust, simply criticizing Labor or claiming the Liberals can “save finances” is insufficient; they need impactful and actionable policy proposals.

The key question remains: Can Wilson, with limited political experience, deliver in the next year, and how will the public respond to her performance?

Parties’ Policies and Attitudes Toward Multicultural Communities

According to the 2021 census, 31.5% of Victoria’s population was born overseas. Many recent immigrants over the past 20–30 years do not traditionally support major parties and often lack firmly established Western-style political positions. Yet, because they now represent an increasingly crucial portion of the electorate, any party that successfully appeals to immigrant voters has a chance to secure key votes.

Immigrant concerns are often not ideological but practical: Are parties willing to listen? Are relations between Australia and their home country favorable? Does the government help immigrants integrate locally?

The Chinese community is particularly attentive to Australia–China relations. Since Andrews’ government, Labor has taken an active approach, including multiple official visits to China. The federal Albanese government’s warming of diplomatic ties, and Allan’s recent facilitation of a Chinese railway delegation exchange, continue this trajectory. For some Chinese voters, this represents stable and friendly policy direction.

Labor has also introduced a series of multicultural initiatives, such as AUD 29 million in additional funding for local news and community broadcasting to support multicultural media development, and the creation of a Multicultural and Multifaith Law Reform Consultative Committee to allow multicultural communities more direct input into Victoria’s legislative process.

Last year, the federal Labor government published the Multicultural Framework Assessment, the first attempt by an Australian government to explore the development of a multicultural society. Federal funding has been pledged to implement recommendations, further advancing the framework.

In September this year, the Victorian Labor government released the Victoria Multicultural Development Blueprint, proposing the establishment of a new statutory body, Multicultural Victoria, and funding for Chinese cultural museums and facilities to directly respond to community needs.

However, promises are easier than delivery. For example, in 2014, Andrews promised land to Chinese and Indian communities for aged care facilities, winning significant immigrant support. In 2018, he promised additional aged care homes for the Chinese community. Yet ten years later, while four parcels of land have been purchased, none have been handed over for construction. This has fueled skepticism that Labor may use immigrant communities for votes without fully delivering.

The Liberal Party historically emphasizes small government and fair systems, but its leadership has limited engagement with immigrant communities and lacks awareness of the challenges newcomers face, resulting in minimal policy investment in multicultural issues. Past leaders, such as Peter Dutton, linked economic and housing pressures to immigration, calling for large cuts, and senior senator Jane Hume publicly labeled Chinese Australians as “spies,” further weakening support.

Although the party has recently attempted to modernize its image and policy platform for youth, women, immigrants, and environmental issues, no concrete policies benefiting immigrant communities have been implemented. Wilson’s proposed policy focus remains on finance, law-and-order, housing, and healthcare, without prioritizing immigrant groups.

Public Perception of Party Handling of Immigration

Australian immigration policy has long been closely watched. Public perception often frames the Liberals as restrictive and Labor as pro-immigration, though the reality is more nuanced. During the pandemic, net overseas migration (NOM) briefly fell below zero, then rebounded rapidly. Some conservatives blamed Labor, though experts note this was largely pandemic-driven rather than policy-driven.

NOM is not directly controlled by government, being determined by natural population flows of arrivals and departures. What is controllable is the permanent and temporary visa system, including skilled migration, family reunification, international students, working holiday makers, and temporary skilled visas.

While the Liberals verbally oppose “high immigration,” over the past 25 years they promoted temporary migration through international students, 457 visas, post-study work rights, and working holiday agreements. Labor, in contrast, has tightened regulations during governance, including capping international student enrollment, increasing labor and education oversight, raising language requirements, and curbing visa abuse. This highlights the gap between rhetoric and policy: Labor speaks pro-immigration but acts cautiously, while Liberals criticize immigration but relax temporary visa rules.

Immigration policy and visa quotas are federal responsibilities; state governments mainly assist with settlement. Victoria’s new immigrant population has risen steadily, closely trailing New South Wales, showing that the state Labor government continues investing in making Victoria attractive for new arrivals.

Rise of a Third Force

With Victoria’s political landscape fragmenting, independents and minor parties are increasingly significant. In Australia, the lower house primarily proposes and passes budgets, while the upper house reviews, amends, and checks legislation. Independent candidates, especially in the upper house, play a key role in representing voter interests and monitoring major party policies to prevent excessive concentration of power.

Moreover, reforms to the upper house voting system may reshape the overall electoral map. Previously, the Group Voting Ticket (GVT) system allowed voters to select a party, with preferences distributed by the party rather than voters. This sometimes enabled low-polling candidates to win unexpectedly, reducing voter control over results.

If GVTs are abolished, voters will assign preferences directly, making vote distribution more transparent and giving independent candidates’ influence a more direct reflection of voter intent, changing strategies and impact in the upper house.

You may like

Raymond Chow

My New Challenge

Over the past few decades, I’ve written numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics. However, last October, I decided to write a book entirely different from anything I had done before, titled Solitary but Not Isolated. I chose to publish it through crowdfunding. Readers interested in supporting this book can visit the following webpage to learn more and help make it a reality.

I attended a rooftop school in Hong Kong for primary education (a unique feature of Hong Kong in the 1960s: temporary classrooms built on top of apartment blocks in resettlement areas to accommodate children who had moved into the district). Resources were extremely limited. In sixth grade, the school principal gave me and seven other students the opportunity to post our writings on the bulletin board every two weeks for the whole school to read. This was my first experience of writing for a public audience.

In secondary school at Queen’s College, the school published the annual magazine The Yellow Dragon, the earliest and longest-running secondary school annual in Hong Kong. My writings were never published there, though my photos occasionally appeared in reports of school activities. At university, I volunteered as editor for a scholarly publication by the Science Society called Exploration, but after two or three years it was discontinued as no one wished to continue it.

During university, I studied mathematics, which required little essay writing—mostly problem-solving. After entering the field of education, I wrote numerous articles on Hong Kong education that were published in newspaper columns. Later, through curriculum development and teacher training in Hong Kong, I had the rare opportunity to write and publish mathematics textbooks spanning from Grade 1 to Form 7—something unprecedented in Hong Kong.

After moving to Australia, I served as editor of the Christian publication Living Monthly, and eventually founded Sameway magazine, which continues today. From the first issue, I wrote the opening column Words of Sameway, and over 21 years, I have written a total of 745 pieces—a record of my life.

Yet writing Solitary but Not Isolated is something I never anticipated doing since I first learned about autism decades ago. Publishing this book is closely connected to my work with Sameway. I can only say this is a new challenge given by God, a chance to take Sameway to a new stage.

Those Who Love Solitude

Solitary but Not Isolated tells the story of a person with autism. Based on her experiences, the Happy Hands Organization has developed a bilingual training program to help autistic individuals transition from school to the workplace. Launched this year, the program aims to support others in similar circumstances.

Most people with autism do not actively seek social interactions. When they do engage with strangers, they may appear difficult to connect with or communicate with, often leading to social neglect or isolation. For parents and family, this creates a lifelong burden. Even those who complete secondary or tertiary education, despite having professional knowledge, often cannot fully utilize their abilities at work because of incomplete social understanding and lack of basic communication skills. Consequently, they are frequently relegated to jobs that do not match their abilities or are assigned work requiring minimal interaction.

Western society’s understanding of autism began with the lifestyle demands of modern life, emphasizing early social engagement and learning in school. Families, having fewer children, often pay close attention to each child’s development and have higher expectations. Over the decades, understanding of autism has evolved—from viewing it as a mental illness to recognizing it as a deviation from typical personality development. Yet how society should assist their growth remains uncertain.

Decades ago, Western focus was on “treating” autism. Research into genetic, environmental, or physical causes has made limited progress. Interventions to change solitary behaviors are also limited—for example, providing speech therapy in childhood or occupational therapy for daily living skills offers only partial support. While societal acceptance and support for autistic individuals have greatly increased, parents feel that more is needed when their children enter adult life and the workforce.

In short, those inclined toward solitude still face a gap in having equal opportunities to thrive socially and professionally.

Understanding Society and the World

Many autistic individuals focus intensely on specific interests, with little experience in social relationships or current events. As adults, this often leads others to perceive them as unaware of society, or even “odd.” In workplaces, where collaboration is essential, they may face exclusion. Many end up in solitary work with minimal social interaction.

Among Chinese communities, first- or second-generation immigrants with autism often face compounded challenges due to limited knowledge of society. Parents, unfamiliar with Australian systems, cannot fully guide their children, and these high-ability individuals rarely integrate with society, limiting opportunities to demonstrate their potential.

In 2024, ABC launched The Assembly, a TV interview program where host Leigh Sales trained 15 autistic individuals to conduct interviews and produce the show. Participants significantly increased their understanding of society and the world, and their communication and social skills improved greatly.

Last year, Sameway had the opportunity to train a bilingual autistic new immigrant, successfully helping her become a magazine editor. Meanwhile, the Happy Hands Organization developed a workplace adaptation program for bilingual, high-functioning autistic individuals. Through four to six months of training, this program offers these often-overlooked individuals a chance to adapt and develop in Australia.

Thus, Sameway is not only an information platform supporting immigrant communities but also provides a development space and opportunities for those with special needs. Readers interested can contact our magazine or the Happy Hands Organization for details.

The Loneliness of Immigrants

Many immigrants arrive in Australia as adults. They often lack opportunities to understand society deeply and, due to work and life commitments, rarely have the time to engage fully with their new environment or develop close relationships with Australians. Consequently, most live within Chinese communities with similar backgrounds. Passive personalities or limited social skills often lead to intense feelings of loneliness.

Leaving their original home and social networks creates a sense of marginalization similar to that experienced by some autistic individuals. Many immigrants are willing to understand and engage with their new society but face personal limitations and a lack of proactive governmental support, leaving them unable to integrate fully into Australian life.

Chinese immigrants, in particular, may rely heavily on long-term Chinese social media and information platforms, further isolating them from the broader society. This social isolation significantly affects their participation and engagement in Australian life.

The goal of Sameway is to assist immigrants in integrating into Australia, fostering participation and engagement in society. We hope that with continued support, we can go further and achieve more.

During the Christmas and New Year period, “Sameway” relocated though only to a spot less than 100 meters across from their original office. It was a tiring task, but we have finally settled in, allowing us to take a longer break during the holiday.

However, the world still undergoes significant changes. The President of Venezuela has been forcibly taken to New York for trial, while the new leader of Venezuela is willing to govern in line with U.S. interests. The longstanding alliance between Europe and the U.S. has become history in light of the U.S. attempt to purchase Greenland. The “Board of Peace” established by Trump requests that nations place the keeping of global peace in his personal hands, but attendees at the invitation include authoritarian dictators who have initiated wars multiple times. The generation that has grown up advocating for global integration, respect for human rights, and peaceful coexistence is now at a lost and confused. Will the world revert to a chaotic state governed by the law of the jungle, where strong countries dominate weaker ones, or can humanity choose to move forward in civilization by learning mistakes from history? We truly have no sure answer.

However, it is a time where the rise of Trump and the increasing power of global far-right political forces, coupled with the internet and social media replacing traditional media as the main source of information for many people. This has led to a society overwhelmed with information and challenges in distinguishing truth from falsehood, which is equally as frightening as an era where information is blocked, preventing access to necessary knowledge.

In Australia, as a multicultural country, immigrants face significant difficulties in obtaining lifestyle information through mainstream media. I believe that to build Australia as a harmonious and cohesive society, the government must invest substantial resources to assist immigrant communities to establish high-quality and credible multicultural media, and to accelerate the integration of first-generation immigrants into society, allowing them to become a driving force in social development.

In the past year, we have strengthened the current affairs information provided on our website. In the coming year, we will focus on enhancing our information services for the Chinese community through our broadcasts and magazine publications. I hope you can support us in achieving the goal of promoting the development of the Chinese immigrant community.

Starting this year, in line with the REJOICE’s initiative for bilingual new immigrants with autism, I will be writing a brand-new column to explore this topic with the community as they navigate With the NDIS program. I hope this innovative program by the REJOICE will receive your support for promotion and development within the community.

Additionally, after three years of training aimed at encouraging seniors to use social platforms to expand their community engagement, we will take a further step this year by launching training courses to assist seniors in using artificial intelligence. Our goal is to help Chinese seniors in Australia stay up-to-date and enjoy a higher quality of life brought about by AI.

In the new year, let us work together to build a stronger local Chinese community.

Since January 20, 2025, when Trump assumed the U.S. presidency once again, domestic issues in America have been frequent and complex, but the world cannot deny that his foreign policy has reshaped the global political landscape, ushering in a new era.

Over the past year, Trump has been extremely proactive in foreign affairs—from Greenland to Venezuela—demonstrating relentless ambition to expand U.S. influence abroad, even amid controversy and the risk of destabilizing other nations.

Prelude to 2025

Let’s briefly review Trump’s major foreign policy actions in 2025.

First, his involvement in the Gaza Strip cannot be overlooked. In February 2025, he publicly stated that the U.S. would play a more active, even leading, role in the region, supporting Israel’s security needs, including strengthening border defense and intelligence sharing. He also attempted to broker ceasefire talks in the U.S.’s name, coordinating Egypt, Qatar, and other countries as intermediaries. By October, Trump personally attended a multilateral meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, pushing for a ceasefire agreement and reconstruction framework between Israel and Hamas.

While opinions on his approach were divided, with some critics arguing that direct intervention could heighten regional tensions, Trump nonetheless reaffirmed America’s influence and presence in Middle Eastern affairs.

Early in 2025, the Trump administration reviewed all foreign aid and temporarily halted military assistance to Ukraine, using it as leverage to push forward negotiations. By mid-March, following U.S.–Ukraine consultations, military and security support resumed, including air defense systems, drone technology, and financial assistance. The U.S. also advocated international sanctions against Russia, such as high-tech export restrictions and asset freezes. These actions demonstrated Trump’s support for strategic allies and further solidified U.S. influence in Europe.

While these events may seem unrelated, they set the stage for early 2026’s diplomatic developments.

The Venezuela Raid

Trump’s most notable action in January 2026 was the sudden capture (or abduction) of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife.

In fact, as early as December 1, 2025, Trump had called Maduro, demanding he step down. When Maduro refused, Trump publicly ramped up pressure in mid-to-late December, applying economic and military pressure—including blockades, intercepting suspicious ships, and bolstering military deployments—to isolate the Maduro government. He even hinted that further U.S. action might follow if Maduro continued to resist, signaling a preemptive warning.

The result: U.S. forces launched a large-scale operation codenamed “Absolute Determination”, storming Caracas, capturing Maduro and his wife, and transporting them to New York for trial. The justification cited Maduro and his inner circle’s involvement in drug trafficking and terrorism, including conspiracies to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. At the same time, Maduro’s government had close ties with China and Russia, who provided military and economic support, posing a threat to U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The operation was also seen as a move to block rival powers from gaining leverage in Venezuela. More importantly, given Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, Trump clearly aimed to reassert U.S. dominance in the hemisphere and secure economic benefits. For many Americans, the raid showcased U.S. military might, boosting Trump’s prestige and approval. True to form, Trump paid little attention to criticism, focusing instead on praise, and was visibly self-satisfied.

International reactions were strong. China and Russia immediately condemned the U.S. action, calling it a severe violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and international law. Iran and other nations with tense U.S. relations also criticized the operation as unilateralism under the guise of anti-drug and anti-terrorism efforts, destabilizing the region.

European responses were mixed. Some EU countries long critical of Maduro still expressed reservations about the U.S. bypassing international authorization for direct military action, emphasizing that even dealing with authoritarian regimes should follow international mechanisms. This tension revealed the strain Trump’s style places on traditional allies.

In Latin America, reactions were split: anti-Maduro governments and Venezuelan opposition privately supported the move as a chance to break political deadlock, while others feared overt U.S. military intervention might revive Cold War-era “Monroe Doctrine” fears, worsening regional security.

Currently, former Vice President Rodríguez serves as interim president of Venezuela, cooperating with the U.S. while maintaining loyalty to the domestic ruling class, keeping the country relatively stable. For Trump, the goal of preventing other powers from gaining influence in the Americas and securing economic gains was achieved. Many Americans saw the raid as a demonstration of military strength, reinforcing Trump’s image as a decisive leader.

Trump’s Greenland Gambit

Since 2025, Trump has repeatedly brought Greenland into the spotlight, making it one of the most challenging and controversial topics of his second term.

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is under Danish sovereignty but enjoys local autonomy. Its location between North America and Europe along the Arctic shipping route has made it strategically valuable. Previously overlooked due to extreme cold, climate change and melting ice have expanded Arctic navigation, increasing Greenland’s military and technological importance. The island also contains vast deposits of rare earth and critical minerals, essential for modern technology and defense systems.

Trump’s assertive approach clearly aimed to maximize U.S. influence over Greenland. In 2025, he publicly expressed interest in buying Greenland and urged negotiations to secure it, even hinting at military options. This escalated tensions with Denmark and Europe.

European reactions were unanimous: Greenlandic leaders stated the island is “not for sale”, and massive protests erupted in Greenland and Denmark. The UK prime minister warned Trump that high tariffs or aggression would be a grave mistake, while EU countries—including Denmark, France, Germany, and the UK—supported Danish sovereignty. Even European far-right parties, traditionally aligned with Trump, criticized his Greenland strategy as overt aggression, causing internal rifts.

At the 2026 Davos World Economic Forum, Trump and NATO Secretary-General Rutte reached a “preliminary framework” focusing on Arctic security cooperation rather than territorial control. Trump framed it as safeguarding U.S. military bases and economic interests, while Denmark retained final authority. However, Greenland’s government stressed it was not fully involved in negotiations, highlighting an ongoing tension. Analysts debate whether this is a tactical retreat or pragmatic compromise.

Even with the temporary easing of tensions, U.S.–Europe trust has been strained, showing how far-reaching Trump’s assertive diplomacy has become.

Iran Unrest and U.S. Pressure

From late December 2025, Iran experienced nationwide protests, initially triggered by economic collapse, currency devaluation, and skyrocketing living costs, evolving into broad dissatisfaction with the regime. The government’s harsh crackdown led to casualties and arrests on a scale unseen since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The U.S., which maintains heavy sanctions against Iran citing terrorism sponsorship and nuclear/military threats, seized this moment to intervene. Trump publicly announced deploying a fleet—including aircraft carriers and missile destroyers—to the Persian Gulf to deter further escalation. He emphasized a preference for avoiding force but warned of potential military action if the regime continued violent repression.

Trump also communicated with Iranian protesters via public statements and social media, encouraging demonstrations and denouncing government violence. He canceled all official diplomatic talks until Tehran ceased the crackdown. While some protesters hoped for U.S. support, the absence of direct action led to frustration and feelings of abandonment.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard leaders warned that any U.S. strike would be considered a full-scale war. Protests and anti-U.S. imagery reflected strong resistance. Intelligence reports indicating a temporary halt in state violence led Trump to consider pausing military actions while closely monitoring the situation, balancing threats with cautious observation.

Trump’s strategy combined military presence and public warnings to pressure Tehran, deter large-scale killings, and strengthen U.S. influence in the Middle East. Yet this high-risk approach also raised the possibility of miscalculations, where tensions could escalate unintentionally, making the U.S. a target for criticism and resistance.

The “Board of Peace”

Traditionally, the U.S. has been seen as the global big brother. But with China’s growing influence and global economic support programs, U.S. presidents often feel impatient with Beijing’s increasing UN sway. Trump, ambitious and assertive, sought to take matters further.

At the 2026 Davos Forum, he launched the “Board of Peace”, initially proposed to address Gaza peace but now expanded to serve as a broader global conflict mediation mechanism. The initiative leverages U.S. influence to create an alternative diplomatic platform and invites multiple countries to participate.

However, critics question whether it is more for show than genuine peacekeeping. The EU’s concern lies less with the stated goals and more with the lack of clarity: the legal status, decision-making process, funding, and international law accountability remain unspecified. Unlike multilateral bodies like the UN or OSCE, this U.S.-backed, president-driven mechanism risks becoming a coercive tool rather than a genuine mediator.

The EU fears it could undermine Europe’s long-standing role in Middle East diplomacy, forcing it from rule-maker to follower. China was excluded, reflecting Trump’s view of Beijing as a competitor, not a partner. The Board aims to present participation as a political statement, effectively creating a U.S.-led bloc in global conflict mediation.

For Australia, the Board is a hot potato. Prime Minister Albanese received an invitation but has not confirmed participation. Several NATO and EU countries have declined, while Canada was disinvited over disagreements on China policy. Thirty-plus leaders who accepted include war actors like Putin and Israel’s Netanyahu. How they could effectively promote peace remains questionable, and handling the invitation diplomatically will test Albanese’s political skill.

Trump’s Diplomatic Logic

Across Gaza, Ukraine, Venezuela, Greenland, Iran, and the Board of Peace, Trump’s strategy is consistent: proactive engagement, pressure, disruption of norms, and forcing allies and adversaries to recalculate. He eschews slow multilateral negotiations in favor of military, economic, and media leverage, coupled with highly personalized decision-making, shifting power quickly at the negotiating table.

To Trump, diplomacy is a continuous game of strategy, not merely maintaining order. He pushes situations to the edge, then retreats strategically to gain advantage. While controversial and eroding trust among allies, it successfully recenters U.S. influence.

Crucially, Trump applies pressure not only to adversaries but to allies, forcing them to demonstrate loyalty or strategic value. This increases U.S. bargaining leverage but consumes trust capital, making international relations more transactional and short-term, and setting the stage for future friction.

Costs and Risks of Assertive Diplomacy

Reliance on pressure and uncertainty may yield short-term results but risks long-term instability. Highly personalized, low-institutional approaches erode trust in rules, procedures, and multilateral cooperation. Misjudgments are more likely in opaque, high-stakes situations. Allies and adversaries may misread threats, escalating conflict even without provocation.

Trump is reshaping U.S. diplomacy from guardian of order to rewriter of order, providing tactical flexibility but weakening institutional credibility. Whether the U.S. can balance assertive pressure with sustained trust will determine its long-term global leadership.

Ultimately, Trump’s strategy may open new strategic space for the U.S. or provoke deeper backlash and confrontation. One thing is certain: the international stage in 2026 is no longer the old world, and Trump is the key variable driving this structural transformation.

Listen Now

Pro-Trump Brazilian Influencer Arrested by U.S. ICE

German Chancellor Merz Discusses “Shared Nuclear Umbrella” with European Allies

Australian Government Unveils Blueprint for Autism and Developmental Delay Programs

One Nation’s “Spot the Westerner” Video Condemned

Littleproud retains leadership, Sussan Ley’s position uncertain

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

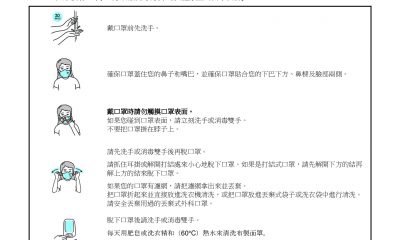

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized6 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單