Understand Australia

Rooted in Australia 1 : The richness of a diverse Australia

Published

2 years agoon

Hong Kong people adapt easily to Australia

Growing up in Hong Kong, I knew I was one of the 4 million people living in the city, which was then known as the Pearl of the Orient. At that time, there was no television broadcasting and of course no internet, but a picture of the night view of Victoria Harbour given to me by my primary school classmates told me how beautiful Hong Kong was. I am proud to be born in Hong Kong, and I have never thought about whether Hong Kong is Chinese or British, but I only know that if I am born in Hong Kong, I am rooted in Hong Kong.

When I was a child, I lived in a resettlement area, which I later learnt was a place where the government resettled fishermen who had no place to live, hut dwellers, or people living on land to be relocated. A family of 10 people lived in a flat of less than 300 square feet, with no indoor water supply, toilet or kitchen. Every day, they had to fetch water from the public hoses to wash their clothes and cook at home, while the toilet was located outside the house and each shared by two families. What was even more interesting was that the primary school I attended was built on the rooftop of the building, and the school didn’t even have a ceiling outside the classrooms. Looking at the colourful Hong Kong on the postcards, I still believe that this is the world-famous Pearl of the Orient. It is because in this difficult environment, millions of people came from China in a short span of 30 to 40 years and established their homes on this piece of land.

When I was in secondary school, I was allocated to Queen’s College, where Dr Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, also once attended, and I was very proud of the school. The classrooms in the school were spacious, bigger than my home with 40 students. That is why I like to stay at the school and consider it my home, and that is why I was fond of Queen Victoria, not thinking of myself as a Chinese, a second-class resident of this land. The good thing is that Queen’s College is a very good school, and most of its graduates have made great contributions to the society, and even some of its alumni have made contributions to China, such as Dr Sun Yat-sen who became the Father of the Nation, Liao Zhongkai who was the leader of the revolution, and Tang Shao-yi who was the first Prime Minister of China, and so on. Life at Queen’s College reminded me that people who grew up in the British colonies did not have to be loyal to the Queen, but could also give their lives to build China. (Duan Chongzhi, the President of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, who resigned last week, was also an alumnus of Queen’s College who had matriculated there for two years.)

In those days, students at Queen’s College could have very different political stances because of its philosophy of education, which encouraged independent examinations. They could become the highest-ranking official in the Hong Kong government like Chief Secretary for Administration Rafael Hui, or they could become patriotic nuisances like Antony Ho and Lee Kai Pan, who were reported to the police by the principal and arrested and jailed for advocating the “downfall of the British Hong Kong Government” during the Riot of 1967, or they could become the “orphaned son” like Szeto Wah, who saw himself as an advocate of love for China in the colonial territories. Growing up in such a society and in such an interesting school, I did not feel any sense of betrayal to the Queen when I emigrated to Australia, since Australia was as loyal to the Queen as Hong Kong. I just felt that I had moved from a society that was once part of the British Empire to another white-dominated society. I could speak English anyway, and with a few adjustments to my lifestyle, it would be no different. It was easy for me to accept myself as an Australian.

Discovering Multicultural Australia

When I became an Australian, I realised that Australia is not Aboriginal, nor is it only British, but it is a diverse place for anyone from all over the world to call home. There is no other country on earth today that is as open to all kinds of people as Australia. It doesn’t matter where you come from, as long as your life doesn’t jeopardise the lives of others, you will be respected, accepted and tolerated in Australia.

The history of this acceptance of diversity is not very long, only about 30 to 40 years. As Australia is far away from the developed western countries, not many rich, cultured and educated people would migrate to Australia from the developed world. From the 1970s onwards, Australia began to absorb non-white immigrants, so that they could establish a home in the same way as other people in this land. Most of these people were not rich, so democracy, freedom, the rule of law, and fairness to ensure that these people can have a chance to make a difference have become the common social values of Australians.

After 2000, when China’s economy took off and wealthy Chinese immigrated to Australia, and the Australian community began to absorb wealthy investment migrants, some people believed that the basic values of the Australian community had been impacted, and recognised that the values of the Australian community were gradually becoming a factor to be considered in immigration policies.

However, up to now, most of the people who come to settle in Australia are from different parts of the world, hoping to build their own future by their own efforts. Therefore, it is still a common value of the Australian society that everyone, including newcomers, should be treated fairly. In fact, from the Census results, we can be sure that today’s Australian society is already extremely diverse, but this is a true picture that not only new and old immigrants, but also the mainstream society here, do not quite understand.

For every immigrant who comes to Australia, we will meet different people in our lives, and gradually through these experiences, we have formed a different understanding of this society. What we don’t realise is that the Australian society we experience is largely determined by the way we choose to live our lives. And whether or not we are satisfied with those experiences is also determined by our choices.

The Hong Kong Community

Most of the people I first met in Australia were immigrants from Hong Kong, like me. Although my sister and brother had married Westerners, I was also surrounded by Australians. But because most of my friends were Hong Kong immigrants like me, and the churches I attended and served for years were Cantonese-speaking immigrant churches, I experienced a community that I chose to be predominantly Hong Kong.

In this community, we often meet professionals from the same background as us, all immigrants who finally chose to leave Hong Kong because of the 1989 pro-democracy movement, and naturally we believe that most Hong Kong people came here for this reason. In fact, this is not the case.

After I started the Sameway magazine, I found that many of the Cantonese-speaking community had come to live in Australia many years ago. They may be from Guangdong, but most of them have lived in Hong Kong, and many of them have lived in Chinatown, so there is not much of a connection between their arrival here and 1997. In the past few years, there have been more new immigrants from Hong Kong, and they are different from the original Cantonese-speaking immigrants. They do not want to see themselves as Chinese, they are dissatisfied with the Chinese government, and they are willing to integrate into the Australian society, but they do not know and are unwilling to accept the Australian way of doing things, and they are even more unwilling to regard Hong Kong immigrants who do not agree with their political beliefs as Hong Kong people.

In fact, Hong Kong immigrants have a very definite meaning, that is, immigrants from Hong Kong to Australia, and it has nothing to do with their acceptance of Hong Kong society, their attitude towards the Communist Party that is ruling China today, nor do they necessarily want to preserve Hong Kong culture, let alone supporting Hong Kong’s resistance. It is obviously we should refer to our identity of where we come from, but not to the various political concepts are added to differentiate us. I think this kind of thinking is not in line with Australia’s social values.

The Chinese community

The Chinese community in Australia is very diverse. They come from different generations and have different backgrounds. Among the Chinese, there are those who came to Australia in the 1980s as publicly-funded students, the so-called “50,000” migrants, investment migrants who came after China’s economic take-off, those who stayed behind and struggled to make a living, and successful retired cadres, entrepreneurs and academics who followed their children to Australia.

These Chinese immigrants from different backgrounds make up Australia’s diverse Chinese community today.

Chinese communities in South East Asia

Even more diverse are the Chinese immigrants from different countries in South East Asia. They may come from Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and so on. They share the same food habits, Confucianism, festivals and customs, or the same Chinese culture, or the same language.

The longer I live in Australia, the more diverse I realise it is. For me, it has enriched my life. In the last few years, I have been attending Western churches, and I have discovered a richer side of them, which I will tell you more about in this column.

Mr Raymond Chow

You may like

Features

A New Chapter for the Liberal Party: Challenges and Opportunities Under Sussan Ley’s Leadership

Published

3 months agoon

July 2, 2025

In the Australian federal election on May 3, 2025, the Liberal Party suffered a crushing defeat, marking its worst election loss in 70 years. This party, which had long dominated Australian politics, was defeated at the polls, leaving party morale at an all-time low and the future direction uncertain.

Amid this low point, Sussan Ley was elected as the new party leader, becoming the first woman to lead the Liberal Party in its history. Her appointment not only symbolizes a breakthrough in terms of generation and gender but is also seen as an opportunity to rebuild the party’s image and political positioning. Whether she can regain voter trust and lead the Liberal Party to a fresh start has become a focal point of public attention.

Last Wednesday, she delivered her first major speech since taking office at the National Press Club. From her words, demeanor, and policies, it is becoming clear that she aims to shape the Liberal Party into a more open, more willing to listen, and more representative of diverse voices.

From grassroots to politics

Sussan Ley was born in 1961 and spent her childhood in Nigeria, the Middle East, and the UK before immigrating to Australia with her parents during her teenage years. Her professional background is diverse, having worked as a pilot, air traffic controller, farm cook, and tax officer. These experiences have given her a deep understanding of grassroots life and policy operations. As a result, she is not as distant as traditional political elites but is closer to ordinary people. She is not a typical politician but has entered the political arena through her own efforts and learning.

In the early stages of her career, she worked while pursuing further education, obtaining qualifications in accounting and taxation. She then joined the Australian Taxation Office, gradually gaining an understanding of policy and public sector operations. These early experiences have enabled her to better understand the realities of ordinary Australians’ lives compared to most politicians who come from party systems, and to establish a practical and people-friendly image.

She also pursued a master’s degree at Charles Sturt University and briefly worked in academia and the field of agricultural policy. This diverse background enables her to excel in parliamentary discussions on rural and regional policies and to build long-term trust with her constituents.

After being elected to the House of Representatives in 2001, she held key positions in the health, education, and environment sectors and served as deputy party leader in 2022. Following her election as party leader after the 2025 federal election, her ascension signifies that the Liberal Party is contemplating how to redefine its values to align with the times. Ley did not rise to power through party factional maneuvering but rather through stable public support and a cross-factional image that earned her the trust of party members, making her a choice to stabilize morale in times of crisis.

It is worth noting that in 2016, she sparked controversy by purchasing a property during a business trip and claiming reimbursement of travelling expenses. Although she did not break the law, she resigned from ministerial position in 2017. The incident shook her reputation for integrity and became a challenge in her political career. However, she retained her parliamentary seat and returned to the policy core, gradually rebuilding her political influence and laying the groundwork for her eventual leadership role.

A leadership style and philosophy distinct from Dutton’s

Although Sussan Ley has only been in office for a very short time, the leadership style she has displayed so far is markedly different from that of her predecessor, Peter Dutton. During his tenure, Dutton was known for his hardline conservative stance, advocating for cracking down on immigration, reducing the size of the federal civil service, and proposing controversial policies such as expanding nuclear energy investment and significantly downsizing the public sector. He also faced criticism for his frequent public gaffes and inconsistent policy positions, further damaging the Liberal Party’s image.

In contrast to Dutton’s authoritarian style and tendency to exclude internal party discussions, Sussan Ley has adopted a markedly different leadership approach. Since taking office, she has emphasized collective participation and party consensus, striving to return the Liberal Party to its traditional “team decision-making” approach. For example, on the highly controversial energy and climate policy, Ley led the establishment of a task force, inviting several shadow cabinet members and backbench MPs from different factions to participate, coordinating the Liberal and National Parties’ positions on “net-zero emissions.” The task force, led by opposition energy spokesperson Dan Tehan, included members such as the shadow treasurer and the head of resources and environmental affairs, reporting directly to Ley and National Party leader David Littleproud, and jointly developing a new direction that balances stable, affordable energy supply with carbon reduction responsibilities. Such a collaborative mechanism not only helps mend internal rifts within the coalition but also demonstrates her willingness to return policy discussions to institutional procedures and collective participation, rather than a one-person dictatorial style.

Sussan Ley and Dutton also hold markedly different positions on the “land acknowledgment” ritual. Dutton has criticized the ritual for being abused and avoided it multiple times during the election campaign; in contrast, Ley proactively performed the acknowledgment in her first major speech after taking office, emphasizing that it holds significant meaning at appropriate times and should not be reduced to a mere formality or completely excluded, demonstrating a more pragmatic and respectful attitude toward multiculturalism.

Sussan Ley has also demonstrated a more open and inclusive leadership style since taking office. In her speech, she emphasized that the Liberal Party must respect and reflect the diversity and vitality of modern Australian society. “This society is composed of people from all over the world, including families raising children in the suburbs, young people striving to develop their careers, renting while pursuing homeownership, and elderly individuals with rich experience who care about the nation’s future.” She also mentioned that professionals, small businesses, volunteers, entrepreneurs, and the working class should all be valued and recognized. Her attitude shows that she values and is willing to listen to the ideas of different groups, respecting the contributions of every Australian.

Sussan Ley has also actively engaged in dialogue with various sectors of society, particularly focusing on reconnecting with young voters who were lost in the previous election. She was interviewed by The Daily Aus on June 15. *The Daily Aus* is one of Australia’s most influential online media outlets, targeting young readers with over 620,000 Instagram followers, and Dutton had previously refused to be interviewed by the media outlet. During the interview, Ley discussed student loan policies (HECS), how young mothers balance family and work, and climate change—issues of concern to young voters. She acknowledged that these are important and urgent challenges, not only critical for young people but also closely tied to the broader Australian society. She emphasized that all political parties should take young people’s voices seriously.

Additionally, she pointed out that for Australians today, the cost of living and rental pressures are the most pressing livelihood issues. Through these concrete actions, Sussan Ley is attempting to convey to the public that the Liberal Party is striving to be more in tune with the general public and to make up for past mistakes in failing to truly understand and represent young people and grassroots voters during elections.

Key policy issues: women, children, and defense

Sussan Ley also clearly articulated the policy issues she prioritizes in this public speech.

Her policy proposals are closely tied to the current international landscape. In the face of escalating conflicts and geopolitical instability, she emphasized that Australia must confront reality and address security challenges head-on. She criticized the Labor government for being insufficiently proactive in defense preparedness, urging Australia to increase its defense budget to 3% of GDP, accelerate the development of military capabilities such as drones, missiles, and space technology, and address the shortage of personnel in the Australian Defense Force. At the same time, she also addressed Australia’s stance toward China, stating that bilateral respect and good relations should be maintained, but that provocative actions such as Chinese military ships patrolling around Australia must be met with a firm response. She emphasized that Australia must confront the competitive and threatening world it now faces and deepen cooperation with its allies.

As a female leader, she also turned her attention to long-neglected social issues. She emphasized that domestic violence and gender-based violence are a national disgrace. Drawing on her personal experiences, she spoke out on behalf of women, expressing understanding for the fear, control, and self-blame they feel, and promising to incorporate this empathy into future decision-making. She also called for the government to allocate more resources and encourage male groups to participate in reforms, arguing that men’s health policies are also part of women’s safety.

Additionally, she has highlighted the challenges children face in the digital age, criticizing tech giants for profiting from addictive designs. She has urged the government to stand with parents to prevent harm from internet addiction, misinformation, and AI abuse. She has specifically pointed out the growing harm deepfakes pose to women.

Internal Reform Challenges

However, Sussan Ley’s reform efforts will face challenges. The Liberal Party remains deeply influenced by the conservative values of the “Robert Menzies era,” with many senior party members holding conservative views on gender equality, climate change, and immigration policies, creating a significant gap with modern voters. The party’s culture has long favored maintaining the existing power structure and traditional values, lacking proactive willingness for institutional reform and ignoring the current trend where voters prioritize social justice, the environment, and inclusivity. This misjudgment has made the Liberal Party’s policies appear outdated, leading to a significant loss of votes from young people and minority groups.

The Liberal Party’s recent election defeats have been particularly severe in some areas, especially in suburban regions that were once long-standing strongholds for the party but are now experiencing voter defections. This indicates a growing disconnect between the party and local grassroots communities. If Leah wants to reverse this trend, she must rebuild substantive relationships with local communities. Sussan Ley has indicated that she will reallocate resources to regional branches to enhance their autonomy and training capabilities, but this will require significant long-term investment.

Moreover, an increasing number of Australian voters, particularly those from multicultural communities and immigrant backgrounds, no longer identify with the “white middle-class” as the mainstream culture. Instead, they expect policies that reflect their diverse identities and experiences. In this context, the Liberal Party’s long-standing political image is gradually losing its influence. The core values of “hard work, family, and entrepreneurial spirit” that were once emphasized must be reinterpreted in today’s diverse immigrant society; otherwise, they will become hollow rhetoric disconnected from the lives of most voters. If Sussan Ley is to successfully lead the Liberal Party through this transformative period, she must actively integrate diverse ethnicities, genders, faiths, and social experiences into mainstream values to create a more inclusive political image.

In recent federal elections, the Liberal Party has clearly lost the support of the majority of multicultural immigrants. To regain their support, the party cannot simply focus on policies to manage immigration numbers but must instead develop concrete plans to assist immigrants in effectively participating in and contributing to multicultural Australia within a short timeframe. In this regard, both the Liberal Party and the Labor Party have yet to propose any concrete solutions. The previous government proposed the Multicultural Framework Review, but no concrete implementation plans have been put forward. If Sussan Ley’s Liberal Party can take the lead in proposing specific policy implementations within this framework, it may have the opportunity to rebuild the Liberal Party’s recognition within the immigrant community.

However, Sussan Ley also faces pressure from hawkish factions within her party, who emphasize “free markets,” “spending cuts,” and “national defense and security first.” This makes any open stance toward immigration risk being viewed as compromise or even betrayal within the party. Ley needs time and strategy to persuade these conservative voices to understand that if the party does not adjust its mindset, it will be left behind by the times.

Additionally, the Liberal Party has long faced criticism over Indigenous affairs, particularly for its conservative stance during the “Indigenous Voice” referendum, which has left the party lacking an effective platform for dialogue with Indigenous communities. While Sussan Ley has not publicly supported this reform, she has stated that the party should establish more substantive partnerships with communities. How she handles this issue in the future will also serve as a key indicator of her leadership’s inclusivity.

Opportunity in Crisis

Sussan Ley adopts a calm and rational communication style, avoiding inflammatory language and shunning media sensationalism. She advocates that the Liberal Party must become more inclusive, truly reflecting the voices of Australia’s diverse modern society. She emphasizes teamwork, thoughtful policy-making, and gradual reform.

In the current context of a diversifying electorate and shifting values, the Liberal Party will struggle to rebuild social trust if it cannot fully shed its past ideological and cultural baggage. As the first female party leader, Sussan Ley’s emergence undoubtedly symbolizes a new beginning for the Liberal Party, but to truly turn the tide, institutional outcomes and policy actions are needed. Whether she can transform her personal experiences into organizational reform momentum will determine the trajectory of her political career and the future of the Liberal Party.

She must actively promote cultural transformation within the party, combining incentive mechanisms with policy support to create space for diverse political participants to thrive. Additionally, addressing global climate issues, digital economic transformation, social inequality, and Indigenous justice requires the Liberal Party to propose more forward-thinking and inclusive policy solutions.

This challenge is not only a test of Sussan Lee’s personal leadership but also a rigorous test of whether the Liberal Party can transform itself into a modern political party.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

Features

Monocultural, Multicultural, and Intercultural Society

Published

4 months agoon

May 23, 2025

Liberal Party fails to recognize multiculturalism

The Liberal Party suffered a massive defeat in the federal election, with Leader Dutton losing the Dickson seat he held for 24 years. The Liberal Party elected Sussan Ley as leader and Ted O’Brien as deputy. Ted O’Brien, who has lived in Taiwan for many years to learn Chinese and managed his family’s business in China, is one of the few Liberal leaders who is familiar with Chinese culture. After his election, Ted said that the Liberal Party needed to renew itself and propose policies that would meet the needs of modern Australia, including rethinking its policies on youth, women, migrants and the environment, or else the Liberal Party would be unable to build a relationship with the Australian electorate and its survival would be in doubt.

The Labor Party, which aims to reform the society, regards migrants, especially those from poor countries, as a disadvantaged group. Therefore, the Labor Party’s policies occasionally help migrants to adapt, and most of the leaders of the Labor Party have a more open attitude towards supporting migrants. The Liberal Party has always emphasized on small government and fairness of the system, and its leadership has little experience with immigrant communities, and basically has little understanding of the difficulties migrants encounter in adapting and integrating into the society, and therefore is not enthusiastic in supporting migrants in its policies.

Over the past two decades, Australia has absorbed more than 200,000 immigrants every year. These new migrants have found that the Labor Party has more policies that benefit migrants, and this has been reflected in the fact that migrants have been more supportive of the Labor Party’s governing in the past elections. In this year’s federal election, the Liberal Party’s Dutton blamed migrants for Australia’s economic pressures and housing shortages, and demanded a drastic reduction in the number of migrants, and senior Senator Jane Hume called Chinese Australians “spies”, which made many migrants detest the Liberal Party. If the Liberal Party still fails to recognize and respond to the reality that Australia has become a multicultural society, we can foresee that the Liberal Party is likely to disappear from the Australian political scene.

Lack of multicultural experience among societal and political leaders

Before the abolition of the White Australia Policy in the 1970s, Australia was a white society, and even the Aboriginal people, who were the owners of the land, were denied and ignored. The Chinese used to make up more than 15% of Australia’s population during the Gold Rush era, but under the White Australia Policy, less than 1% of Chinese Australians remained in the 1970s. In terms of today’s universal values, the Australian government had implemented a “non-violent” policy of genocide. In fact, the Stolen Generation’s policy of handing over Aboriginal babies to white people for upbringing and education was similar. The Racial Discrimination Act of the 1970s officially ended this phase of Australia’s history, but it did not mean that Australia immediately entered a multicultural society.

Australians born before the 1990s grew up with very little contact with people of other ethnicities in their communities and lives, so racial discrimination was rampant at that time. Nowadays, most of the Australian leaders in their 40s and 50s were born in the 1980s or before. Although they accept the diversity of the Australian society today, they have never had much personal experiences with multicultural communities or migrants, and therefore seldom consider things from the perspective of a multicultural society in their policy implementation or management. For example, many managers of mainstream organizations or enterprises deeply understand that they need to enter the multicultural community in order to continue their current market or organizational goals, but they do not know how to intertct with hese communities. In Australian society, the Australian Football League (AFL) have demonstrated a determination and experience to become multicultural, as many of the AFL’s past leaders have come from multicultural backgrounds.

Similar scenarios are reflected in politics and social management, that is, when the government implements a policy, it often fails to get a response from the whole society. For example, the NDIS, which was legislated in 2013, still has less than 9% of participants from multicultural backgrounds, which is less than 40% of the original expectation. Obviously, a policy that aims to benefit people with disabilities across the country has failed to reach out to ethnic minority communities, and has resulted in many cases of abuse and misuse. It is totally unacceptable but little complaints has been made by neither mainstream Australians nor ethnic communities. Other example is services to help families troubled by gambling, which have not been used by many migrants for a long time. For many years, the organizations concerned thought that the problem was that migrants were reluctant to use their counseling services, but the truth is that these services are provided according to the Western individualistic medical model, rather than seeing gambling as a social problem that brings difficulties to the family members, let alone dealing with the problem by promoting it to the multicultural community. During the Covid pandemic, the Victorian government’s publicity of anti-epidemic measures neglected the role of multicultural media, which initially led to a situation where the infection and death rates of overseas-born people were twice as high as those of local-born people in the.early days.

Diversity in Australian Society

The Australian Bureau of Statistics recently announced that the proportion of overseas-born Australians in the population has increased to 31.5%, in response to the large number of migrants to Australia over the last 20 years. Until the early 1990s, the proportion of foreign-born people was not as high as this, and most of these people came from the United Kingdom, which was close to their cultural background, so the Australian society was not pluralistic, and it could be said that Australia was a monocultural British society at that time. At the time of the founding of the Liberal Party, Robert Menzies was confronted with such a monocultural society. Nowadays, Australia is the most multicultural society in the world. Obviously, the design and implementation of policies must take this factor into consideration.

The Labor Party’s support for multiculturalism basically allows immigrants to continue to retain their native customs, festivals and celebrations, and to tolerate each other in order to maintain respect and peace among communities. Such a society does not mean that there is communication or integration between communities. In fact, a society with no communication or integration will easily be segregated nto competing and opposing groups. It is not easy to maintain harmony and cohesion in such a society.

Last year, the Labor Party released the Multicultural Framework Review report, which was the Australian government’s first attempt to explore what kind of multicultural society Australia could become. The Commonwealth Government has so far indicated that it is also willing to provide funding support to take forward the report’s recommendations to further the realization of the framework. The report’s emphasis on the creation of a multicultural society in Australia, beginning with the recognition that Australian society started from Aboriginals, rather than solely a colonial society created by the British, is a progressive perspective in which migrants of different cultures are welcomed and accepted as part of the Australian society and culture. This means that Australia should not be a society divided by different cultural communities, but rather a modern Australia that integrates and embraces cultures from different places.

Integration into Intercultural

In order to build an integrated and inclusive society, the government has a responsibility to help migrants from all sides of the world, especially those from authoritarian societies, to experience Australian values that are different from their own, including freedom, equality, the rule of law, and human rights. Of course, migrants from non-English speaking backgrounds need to learn English and try to engage with the wider community, rather than being isolated in a culturally homogeneous migrant community.

For young migrants, this is not too difficult. Through the work environment, through life contacts, through community involvement, we see that the new generation is integrating without great difficulty. But for first generation immigrants, it is the government’s responsibility to create opportunities for them to gain exposure and experience in integration. This does not mean that the government is giving resources to migrants as a form of welfare, but rather as an investment by the community in migrants to integrate them into Australian society in the short term, so that they can contribute to Australian society as soon as possible. Such a policy would bring positive returns to the community, and would enable the migration program to maximize the social contribution of the elite settling in Australia.

Another group that has been neglected for a long time is those who were born and raised in the mainstream society. The government should also provide opportunities for them to develop through exposure to multiculturalism. For example, many traditional churches in Australia have been unable to absorb multicultural Christians and have eventually shrunk or even closed down. This is the result of not being able to keep up with the societal changes.

The unwritten expectation of Australian society has always been that newcomers will become mainstream Australians. I believe this is impossible. The challenge for Australia today is for all Australians, immigrants and native Australians (including Aboriginal Australians), to transform and integrate into modern Australians.

Mr. Raymond Chow

Features

Chinese Aboriginals – A History that may Precede Captain Cook

Published

4 months agoon

May 23, 2025

Last Friday, a book launch at the University of Melbourne’s AsiaLink Sidney Myer Centre brought out a powerful message. The Aboriginal people who have lived in Australia for more than 60,000 years are not just modern-day ‘living fossils’. Throughout their history, they have had contact with islanders from the South Pacific and explorers from Japan and East Asia in search of a better life, and they have been a part of Aboriginal culture. Mr. Zhou Xiaoping, an artist living amongst the Aboriginal people, compiled “Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese People in Australit” to introduce Aboriginal Chinese to Australians. Mr. Zhou’s research is now on display at the National Museum in Canberra, and through the book, “Our Stories”, some of the voices of Aboriginal Chinese are being presented to the Australian community.

Forgotten Chinese

In recent years, the voices of the Chinese community have started to be heard in Australia’s multicultural society. Concerns have been raised about the welfare of first-generation Chinese elders, as well as the education of their children and their lives. However, there is a group of Chinese who have long been forgotten, not only by the Chinese or the mainstream community, but also by themselves who have had little contact with other Chinese immigrants: they are the Chinese Aboriginal people, whose identity was often forgotten by the society until recently.

It is only in recent years, with the efforts of scholars, artists and community workers, that this hidden part of history has begun to emerge. One such artist is Chinese-Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping. Recently, he and his team have interviewed this group of mixed-race descendants of Chinese and Aboriginal people who are living among the Aboriginal community to tell their own stories through an exhibition and a book, “Our Stories”, to bring the existence of Aboriginal Chinese into the public eye again.

For Chinese immigrants who have settled in Australia in recent years, or who have been living in the mainstream Australian society since the Gold Rush era, it may never have occurred to us that some of the Aboriginal people, who have a history of 60,000 years and are regarded as the “living fossils” of the modern age, have Chinese cultural heritage since the Gold Rush era. Some Aboriginal leaders even believe that the contact between Chinese and Aboriginal people predates the British declaration of Australia as an uninhabited land. If contact between the Chinese and the Aborigines had been established earlier, then the Aborigines would not be the “living fossils” that the British claimed they were.

Who are the Aboriginal Chinese?

For many newcomers, the first impression of Australia is of a white-dominated, English-speaking society with a colonial past. But the cultural roots of this land are much more complex than that. Aboriginal communities have lived here for tens of thousands of years, and these communities are widely dispersed, with more than 250 language groups, each with their own unique language, culture and lifestyle. They have a deep connection to the land. Aboriginal people do not have the concept of private property, nor do they settle along rivers like other ancient peoples. Instead, they lived in groups, roamed the same area, and made their living by picking natural plants or simply growing them. They believed that people did not own the land, but belonged to it, and were “custodians of the land”, representing it and welcoming others to share its produce. This is why Aboriginal people are often invited to lead welcoming ceremonies at major events in Australia today.

Before the Gold Rush, as early as the 1840s, contract laborers from Xiamen, China, arrived in Australia to work as sheepherders to fill the demand for labor. They did not live in the big cities, even Melbourne was not yet developed. These Chinese sheep herders were scattered around the countryside on farms. Later, the gold rush that swept through Australia, and the establishment of New Gold Mountain in Victoria, attracted more Chinese immigrants to settle in places like Ballarat to participate in gold mining.

Initially, Aboriginal attitudes towards Asian immigrants were the same as those towards European colonizers – they were all foreigners, strangers entering a traditional territory. Interaction was limited by language and cultural differences. However, under colonial expansion and the White Australia Policy, both Aboriginal and Chinese were discriminated against and ostracized, and this common situation unexpectedly brought them closer together.

As the Aboriginal system of closed marriages was destroyed, some Chinese began to intermarry with Aboriginal people to form families, resulting in the birth of Aboriginal descendants of Chinese descent. Their stories are testimonies of how they have crossed cultural boundaries and traumatized by history.

Journey to the Roots: From Confusion to Recognition

In Our Stories, a book curated by Zhou Xiaoping, a number of Aboriginal Chinese descendants are interviewed. In Our Stories, Zhou interviewed a number of Aboriginal Chinese descendants who have pieced together their roots through the memories of their grandparents, family legends and historical archives. Some grew up wondering why they looked different from other Aboriginal people, until one day they asked, “Why do I look different? This began the journey of finding their roots.

“I don’t know how to explain who I am because I don’t know myself,” said one respondent. It was only through oral family narratives and self-study that he slowly came to understand his cultural and historical origins.

Broome, a small town of 14,000 people in the far north of Western Australia, has been a center of multiculturalism since the 19th century. Chinatown, in the heart of the city, is a symbol of this multiculturalism. Its history dates back to the end of the 19th century, when Broome quickly became the center of the pearl industry due to the abundance of shells, attracting migrants from China and Japan to work in the pearl mining industry. In today’s cemetery in Broome, there are more than 900 graves of settlers from Japan. Not only Chinese and Japanese, Broome was also a place where Malays, Pacific Islanders, Filipinos and others came to settle. Broome was not affected by the “White Australia Policy” of the time, as its bead mining industry relied heavily on the skills of Asian divers.

These Asian immigrants lived mainly in what came to be known as ‘Chinatown’, alongside the local Aboriginal Yawuru community. The architecture of Chinatown at the time was unique, blending Asian architectural features with the local climate, resulting in sturdy corrugated iron buildings with reddish-green beams and columns, a fusion of East and West.

One respondent said, “Broome is a place where people know that we can live together from different countries”. These words are a testament to the reality of the history of the Broome.

Chinese immigrants and ‘custodians of the land’

Aboriginal Australians do not see themselves as ‘landowners’, but as custodians of the land. Their culture is so closely tied to the land that even today, when most of them live in modern cities, they continue to carry on their traditions in different ways.

In various public settings, “Welcome to Country” or “Acknowledgement of Country” have become commonplace. These ceremonies remind us that this land belongs first and foremost to the Aboriginal people, and that this recognition is not only a ritual, but also a form of revision and respect for history.

However, on this year’s ANZAC Day, when former Opposition Leader Dutton openly objected to the ‘welcoming ceremony’, it once again triggered a discussion on historical memory and respect. What is the minimum respect for the past? Who is qualified to define “Australian”?

Since the end of the White Australia Policy in 1973, Australia has re-admitted migrants from different countries, but there are still many Australians who have yet to embrace multiculturalism. There has been a rapid growth in Chinese migrants from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia. In practice, however, many migrant families face the tensions of cultural identity: first-generation immigrants struggling to establish themselves in a foreign land, with language and cultural barriers, but still wanting to pass on their culture to the next generation. Their children, on the other hand, have grown up in a Western educational system and are often caught between two values: being seen as outsiders and being expected to be a ‘model minority’. How can outsiders be accepted and integrated by the indigenous people?

Against this backdrop, the stories of the indigenous Chinese provide a different perspective. Their experience is even more complex: they are both Chinese and Aboriginal, but often not fully accepted by either. They are not only the absentees of history, but also the victims of institutionalized forgetfulness. In Our Story, however, they speak of the complexity, or rather the diversity, of their identities, but also of the protection of their land, and perhaps this is one of the things that immigrants need to learn. Perhaps this is the point that immigrants need to learn.

Earlier than Captain Cook

The keynote speaker at the book launch of Our Story was Melbourne University anthropologist and geographer Professor Marcia Langton. Langton, 74, is not only a distinguished scholar, but also a renowned author and Aboriginal rights advocate, a Queenslander of Yiman and Bidjara Aboriginal descent, who traveled around Australia as a schoolboy, worked hard to become a scholar, and has been a longtime campaigner for Aboriginal rights. Langton said that Australians have always thought that Aboriginal culture is old and outdated and cannot keep up with modern society, but they have never thought that Aboriginal people have had contact with other ethnic groups in the past tens of thousands of years before the white people came to Australia.

Langton believes that a deeper study of Aboriginal culture can reveal Australia’s most multicultural traditions, and that Aboriginal culture is the starting point of a multicultural Australia.

Multiculturalism is more than superficial

Australia has been a multicultural nation since the 1970s. From the implementation of multiculturalism policies since the 1970s, to the release of the Multiculturalism Framework Review report in late July 2024, it has been emphasized that multiculturalism is at the heart of the nation’s social structure, and that the freedom of language, religion and cultural practices of different ethnic groups must be guaranteed in law. However, this kind of pluralism sometimes remains on the surface. Every year during the Lunar New Year, dragon and lion dances and Chinese art are used to decorate public institutions. This kind of ritual becomes a symbol of political correctness, but it does not help to truly understand and respect cultural differences. The structural problems of poverty, lack of education and health resources for Aboriginals, and the discrimination and misunderstanding of the Chinese community in the mainstream media are still deeply rooted in the non-European white community, resulting in the phenomenon of so-called ‘depoliticized multiculturalism’.

Such multiculturalism maintains a consumerist cultural identity, but does not truly deconstruct the white-centered social structure. The existence of Aboriginal Chinese is a challenge to this institutionalized forgetfulness. Excluded from the mainstream Chinese narrative and not included in Aboriginal or colonial history, they are ghosts of history. If we do not face up to this past, contemporary multiculturalism will only remain superficial and will not be able to promote real social integration.

Therefore, true cultural integration does not only require minority groups to give up their ego to cater to the mainstream, but also allows each identity to be seen, understood and respected. Just as Zhou Xiaoping has brought Aboriginal culture to Chinese communities in China and Australia through his art, he has also brought Chinese culture into the Aboriginal world. His action is not just an art exhibition, but a starting point for cross-cultural dialogues.

Listening to one more story and recognizing one more piece of history is the first step to dismantle prejudices and gaps.

For many Chinese, their knowledge of Aboriginal people is still limited, even in the form of travel guides or media stereotypes. But when we begin to understand that those who are Chinese, but not like us, are also a mix of Aboriginal people, and how they live with people of different nationalities in their communities, we realize that multiculturalism in Australia is not a product of policy, but a reality that has existed for a long time in the depths of history.

As one of the interviewees in Our Stories says, “My ancestors came here a hundred years ago, and although we’ve been unspoken of for a long time, we’ve never forgotten who we are”. Such voices remind us that identity is not a single lineage or language, but a weave of histories, memories and experiences.

These are the stories that will help us understand what it means to be ‘Australian’ again, and that will open up more possibilities for imagining Australia’s future.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

Listen Now

QantasLink Considers Closing Staff Bases in Canberra, Hobart, and Mildura

ACMA Issues Warning to “The Kyle and Jackie O Show”

British Primatologist Jane Goodall Passes Away

NSW Police Urged to Stop Strip-Searching People

Israeli Navy Intercepts “Global Sumud” Aid Flotilla; Greta Thunberg Detained

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

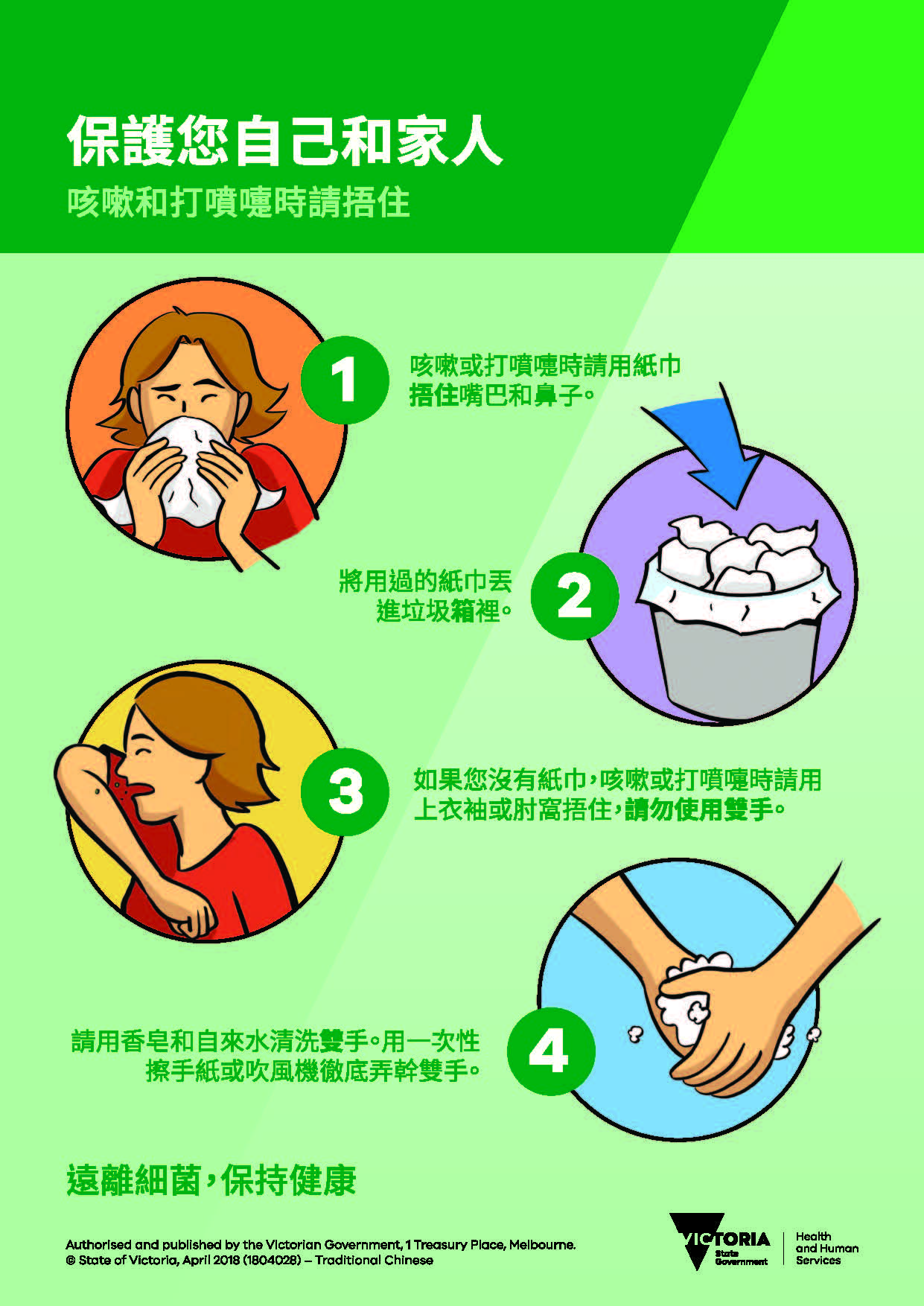

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

U.S. Investment Report Criticizes National Security Law, Hong Kong Government Responds Strongly

China Becomes Top Destination for Australian Tourists, But Chinese Visitor Return Slows

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Albanese Visit to UK Focuses on Domestic Reform, Not Republican Debate

Optus Faces Another “000” Outage, Singtel Bonus Sparks Controversy

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保護您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打噴嚏時請捂住