Features

Chinese Aboriginals – A History that may Precede Captain Cook

Published

7 months agoon

Last Friday, a book launch at the University of Melbourne’s AsiaLink Sidney Myer Centre brought out a powerful message. The Aboriginal people who have lived in Australia for more than 60,000 years are not just modern-day ‘living fossils’. Throughout their history, they have had contact with islanders from the South Pacific and explorers from Japan and East Asia in search of a better life, and they have been a part of Aboriginal culture. Mr. Zhou Xiaoping, an artist living amongst the Aboriginal people, compiled “Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese People in Australit” to introduce Aboriginal Chinese to Australians. Mr. Zhou’s research is now on display at the National Museum in Canberra, and through the book, “Our Stories”, some of the voices of Aboriginal Chinese are being presented to the Australian community.

Forgotten Chinese

In recent years, the voices of the Chinese community have started to be heard in Australia’s multicultural society. Concerns have been raised about the welfare of first-generation Chinese elders, as well as the education of their children and their lives. However, there is a group of Chinese who have long been forgotten, not only by the Chinese or the mainstream community, but also by themselves who have had little contact with other Chinese immigrants: they are the Chinese Aboriginal people, whose identity was often forgotten by the society until recently.

It is only in recent years, with the efforts of scholars, artists and community workers, that this hidden part of history has begun to emerge. One such artist is Chinese-Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping. Recently, he and his team have interviewed this group of mixed-race descendants of Chinese and Aboriginal people who are living among the Aboriginal community to tell their own stories through an exhibition and a book, “Our Stories”, to bring the existence of Aboriginal Chinese into the public eye again.

For Chinese immigrants who have settled in Australia in recent years, or who have been living in the mainstream Australian society since the Gold Rush era, it may never have occurred to us that some of the Aboriginal people, who have a history of 60,000 years and are regarded as the “living fossils” of the modern age, have Chinese cultural heritage since the Gold Rush era. Some Aboriginal leaders even believe that the contact between Chinese and Aboriginal people predates the British declaration of Australia as an uninhabited land. If contact between the Chinese and the Aborigines had been established earlier, then the Aborigines would not be the “living fossils” that the British claimed they were.

Who are the Aboriginal Chinese?

For many newcomers, the first impression of Australia is of a white-dominated, English-speaking society with a colonial past. But the cultural roots of this land are much more complex than that. Aboriginal communities have lived here for tens of thousands of years, and these communities are widely dispersed, with more than 250 language groups, each with their own unique language, culture and lifestyle. They have a deep connection to the land. Aboriginal people do not have the concept of private property, nor do they settle along rivers like other ancient peoples. Instead, they lived in groups, roamed the same area, and made their living by picking natural plants or simply growing them. They believed that people did not own the land, but belonged to it, and were “custodians of the land”, representing it and welcoming others to share its produce. This is why Aboriginal people are often invited to lead welcoming ceremonies at major events in Australia today.

Before the Gold Rush, as early as the 1840s, contract laborers from Xiamen, China, arrived in Australia to work as sheepherders to fill the demand for labor. They did not live in the big cities, even Melbourne was not yet developed. These Chinese sheep herders were scattered around the countryside on farms. Later, the gold rush that swept through Australia, and the establishment of New Gold Mountain in Victoria, attracted more Chinese immigrants to settle in places like Ballarat to participate in gold mining.

Initially, Aboriginal attitudes towards Asian immigrants were the same as those towards European colonizers – they were all foreigners, strangers entering a traditional territory. Interaction was limited by language and cultural differences. However, under colonial expansion and the White Australia Policy, both Aboriginal and Chinese were discriminated against and ostracized, and this common situation unexpectedly brought them closer together.

As the Aboriginal system of closed marriages was destroyed, some Chinese began to intermarry with Aboriginal people to form families, resulting in the birth of Aboriginal descendants of Chinese descent. Their stories are testimonies of how they have crossed cultural boundaries and traumatized by history.

Journey to the Roots: From Confusion to Recognition

In Our Stories, a book curated by Zhou Xiaoping, a number of Aboriginal Chinese descendants are interviewed. In Our Stories, Zhou interviewed a number of Aboriginal Chinese descendants who have pieced together their roots through the memories of their grandparents, family legends and historical archives. Some grew up wondering why they looked different from other Aboriginal people, until one day they asked, “Why do I look different? This began the journey of finding their roots.

“I don’t know how to explain who I am because I don’t know myself,” said one respondent. It was only through oral family narratives and self-study that he slowly came to understand his cultural and historical origins.

Broome, a small town of 14,000 people in the far north of Western Australia, has been a center of multiculturalism since the 19th century. Chinatown, in the heart of the city, is a symbol of this multiculturalism. Its history dates back to the end of the 19th century, when Broome quickly became the center of the pearl industry due to the abundance of shells, attracting migrants from China and Japan to work in the pearl mining industry. In today’s cemetery in Broome, there are more than 900 graves of settlers from Japan. Not only Chinese and Japanese, Broome was also a place where Malays, Pacific Islanders, Filipinos and others came to settle. Broome was not affected by the “White Australia Policy” of the time, as its bead mining industry relied heavily on the skills of Asian divers.

These Asian immigrants lived mainly in what came to be known as ‘Chinatown’, alongside the local Aboriginal Yawuru community. The architecture of Chinatown at the time was unique, blending Asian architectural features with the local climate, resulting in sturdy corrugated iron buildings with reddish-green beams and columns, a fusion of East and West.

One respondent said, “Broome is a place where people know that we can live together from different countries”. These words are a testament to the reality of the history of the Broome.

Chinese immigrants and ‘custodians of the land’

Aboriginal Australians do not see themselves as ‘landowners’, but as custodians of the land. Their culture is so closely tied to the land that even today, when most of them live in modern cities, they continue to carry on their traditions in different ways.

In various public settings, “Welcome to Country” or “Acknowledgement of Country” have become commonplace. These ceremonies remind us that this land belongs first and foremost to the Aboriginal people, and that this recognition is not only a ritual, but also a form of revision and respect for history.

However, on this year’s ANZAC Day, when former Opposition Leader Dutton openly objected to the ‘welcoming ceremony’, it once again triggered a discussion on historical memory and respect. What is the minimum respect for the past? Who is qualified to define “Australian”?

Since the end of the White Australia Policy in 1973, Australia has re-admitted migrants from different countries, but there are still many Australians who have yet to embrace multiculturalism. There has been a rapid growth in Chinese migrants from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia. In practice, however, many migrant families face the tensions of cultural identity: first-generation immigrants struggling to establish themselves in a foreign land, with language and cultural barriers, but still wanting to pass on their culture to the next generation. Their children, on the other hand, have grown up in a Western educational system and are often caught between two values: being seen as outsiders and being expected to be a ‘model minority’. How can outsiders be accepted and integrated by the indigenous people?

Against this backdrop, the stories of the indigenous Chinese provide a different perspective. Their experience is even more complex: they are both Chinese and Aboriginal, but often not fully accepted by either. They are not only the absentees of history, but also the victims of institutionalized forgetfulness. In Our Story, however, they speak of the complexity, or rather the diversity, of their identities, but also of the protection of their land, and perhaps this is one of the things that immigrants need to learn. Perhaps this is the point that immigrants need to learn.

Earlier than Captain Cook

The keynote speaker at the book launch of Our Story was Melbourne University anthropologist and geographer Professor Marcia Langton. Langton, 74, is not only a distinguished scholar, but also a renowned author and Aboriginal rights advocate, a Queenslander of Yiman and Bidjara Aboriginal descent, who traveled around Australia as a schoolboy, worked hard to become a scholar, and has been a longtime campaigner for Aboriginal rights. Langton said that Australians have always thought that Aboriginal culture is old and outdated and cannot keep up with modern society, but they have never thought that Aboriginal people have had contact with other ethnic groups in the past tens of thousands of years before the white people came to Australia.

Langton believes that a deeper study of Aboriginal culture can reveal Australia’s most multicultural traditions, and that Aboriginal culture is the starting point of a multicultural Australia.

Multiculturalism is more than superficial

Australia has been a multicultural nation since the 1970s. From the implementation of multiculturalism policies since the 1970s, to the release of the Multiculturalism Framework Review report in late July 2024, it has been emphasized that multiculturalism is at the heart of the nation’s social structure, and that the freedom of language, religion and cultural practices of different ethnic groups must be guaranteed in law. However, this kind of pluralism sometimes remains on the surface. Every year during the Lunar New Year, dragon and lion dances and Chinese art are used to decorate public institutions. This kind of ritual becomes a symbol of political correctness, but it does not help to truly understand and respect cultural differences. The structural problems of poverty, lack of education and health resources for Aboriginals, and the discrimination and misunderstanding of the Chinese community in the mainstream media are still deeply rooted in the non-European white community, resulting in the phenomenon of so-called ‘depoliticized multiculturalism’.

Such multiculturalism maintains a consumerist cultural identity, but does not truly deconstruct the white-centered social structure. The existence of Aboriginal Chinese is a challenge to this institutionalized forgetfulness. Excluded from the mainstream Chinese narrative and not included in Aboriginal or colonial history, they are ghosts of history. If we do not face up to this past, contemporary multiculturalism will only remain superficial and will not be able to promote real social integration.

Therefore, true cultural integration does not only require minority groups to give up their ego to cater to the mainstream, but also allows each identity to be seen, understood and respected. Just as Zhou Xiaoping has brought Aboriginal culture to Chinese communities in China and Australia through his art, he has also brought Chinese culture into the Aboriginal world. His action is not just an art exhibition, but a starting point for cross-cultural dialogues.

Listening to one more story and recognizing one more piece of history is the first step to dismantle prejudices and gaps.

For many Chinese, their knowledge of Aboriginal people is still limited, even in the form of travel guides or media stereotypes. But when we begin to understand that those who are Chinese, but not like us, are also a mix of Aboriginal people, and how they live with people of different nationalities in their communities, we realize that multiculturalism in Australia is not a product of policy, but a reality that has existed for a long time in the depths of history.

As one of the interviewees in Our Stories says, “My ancestors came here a hundred years ago, and although we’ve been unspoken of for a long time, we’ve never forgotten who we are”. Such voices remind us that identity is not a single lineage or language, but a weave of histories, memories and experiences.

These are the stories that will help us understand what it means to be ‘Australian’ again, and that will open up more possibilities for imagining Australia’s future.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

You may like

This year, the world has continued to pass through turmoil.

Israel has temporarily stopped its attacks on Gaza. I hope that this region, after nearly 80 years of conflict, can finally move toward peace. I remember when I was young, I believed that this land was given by God to the Israelites, and therefore they had the right to kill all others in order to protect the land that belonged to them. I can only admit my ignorance. Yet this did not cause me to lose my faith; rather, it taught me to seek and understand the One I believe in amid questioning and doubt.

December is the time when we remember the birth of Jesus Christ—a season when people would bless one another. Sameway sends blessings to every reader, whether you are in Australia or gone overseas. May you experience peace that comes from God, and not only enjoy a relaxing holiday with your family, but also share quality time together. Our colleagues will also take a short break, and we will resume publication in early January next year, journeying with our readers once again.

While our office will be relocating, the daily news commentary we launched on our website this year will continue throughout this period though. Our transformation of Sameway into a multi-platform Chinese media outlet will also continue next year. It is your support that convinces us that Sameway is not just a publication—it is a calling for a group of Christians to walk with the Chinese community. It is also the blessing God wants to bring to the community through us. We hope that in the coming year, Sameway will continue to stand firm as a Chinese publication committed to speaking truth.

Today, anyone making a request to U.S. President Trump must first praise his greatness and contributions—no different from the Cultural Revolution-style rhetoric we despise. Western politicians call this “political reality.” Russia, as an aggressor, shamelessly claims to “grant” conditions for peace to Ukraine, and other Western leaders must endure and compromise. Australians continue to face economic and living pressures, and immigrants are still scapegoated as the root of these problems, leaving people anxious. Sadly, last week Hong Kong suffered a once-in-a-century fire disaster, causing 151 deaths and the destruction of countless properties—a heartbreaking tragedy. Even more tragic is witnessing the indifference of Hong Kong officials responsible for the incident, and the fact that Hong Kong has now been fully absorbed into the Chinese model of governance—an authoritarian system dominated entirely by “national security” or the will of its leaders, where no one may question the truth of events or demand government accountability.

Yet, in the midst of such helplessness, I still believe that the God who rules over history is the same God who loves humanity—who gave His only Son Jesus to the world to redeem humankind.

Wishing all our readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! See you next year.

Mr. Raymond Chow, Publisher

A massive fire has revealed to the world the hardships Hong Kong society is currently facing. Seven 31-storey buildings—with roughly 1,700 units—were destroyed in a 43-hour blaze, leaving nearly two thousand families homeless. The 156 people who died, including many elderly residents and the domestic workers who cared for them, left their families devastated: most victims simply had no chance to escape because the flames spread rapidly and the fire alarm never sounded. The shocking footage—resembling iconic scenes from a disaster film—circulated online within a single day, prompting many to ask: Is this the suffering now endured by the place once known as the “Pearl of the Orient”?

World leaders offered their condolences to Hongkongers. Chinese President Xi Jinping expressed sorrow for the victims and extended sympathy to their families and survivors. Pope Leo XIV and King Charles III conveyed their condolences; Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese expressed care and support for Hong Kong people. Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing immediately donated HKD $80 million for disaster relief and distributed emergency aid, earning widespread approval. Citizens brought clothes, food, and supplies to the disaster site to help affected residents, showing a spirit of mutual aid in times of hardship.

During the fire, many waited anxiously near the site, hoping their loved ones would emerge safely. For those who reunited with family, there was relief—an ember of hope amid catastrophe. But others were forced to accept, in an instant, that their loved ones had been burned to death, reduced to ashes, having suffered unbearable agony in their final moments. Their grief, anger, and pain naturally lead to a single question: Who will be held accountable for this?

Yet the response from senior Hong Kong officials has been deeply disappointing.

A Government That “Cannot Be Wrong”

The Hong Kong government’s first reaction was astonishing: it blamed the fire on the use of bamboo scaffolding and immediately pushed for legislation to ban bamboo scaffolds. Without proper investigation, the government casually pinned the problem on bamboo, leaving the public with the impression that officials were merely searching for a “not us” excuse—an attitude cold and indifferent to human life.

Yet the footage showed the opposite. The falling bamboo poles were not on fire; instead, flames raced along the sheets of netting wrapped around the buildings. The blame placed on bamboo looked like a crude attempt to deflect responsibility.

When it was later suggested that non-compliant, flammable netting was the real reason the fire spread so quickly, the relevant bureau chief hastily declared that the materials had “been verified as compliant,” prompting widespread disbelief. Those who questioned the government were then accused of “inciting hatred” or being “troublemakers”—a clear reflection of the post-2019 logic in Hong Kong: the government is always right, and anyone who questions it is subversive.

While the entire city was gripped by shock and grief, authorities chose repression over empathy, acting as if heavy-handed tactics could simply bury public anger. This showed a profound misunderstanding of Hong Kong’s unique social fabric and international context. With the world watching, expecting Hongkongers to react like citizens long conditioned under an authoritarian regime in the mainland revealed a startling lack of political awareness.

As a result, Hongkongers across the globe—supported by international media—laid bare the deeper societal, structural, and governance failures behind the fire.

A Government Accountable to the People

Democratic governments may be inefficient or inconsistent, but those that ignore their people for too long ultimately get voted out. Thus they at least claim accountability. In disasters, the most essential response is empathy and acknowledgment of public concerns—not suppression or demands for silence.

The Hong Kong fire has drawn global attention, causing many to suddenly re-examine the skyscrapers built worldwide over recent decades. No matter the country, these massive structures can become sources of catastrophe. I still remember watching Paul Newman’s 1974 classic The Towering Inferno, a film built around fears of high-rise disasters: a 138-storey skyscraper becomes an inferno during its opening ceremony because of cost-cutting and substandard safety systems. The film’s message was clear—human arrogance and greed can turn innovation into tragedy.

Hong Kong’s dense population means high-rise living is long normalized; Australian cities like Melbourne and Sydney have similarly embraced this lifestyle. But have we truly learned how to live safely in such environments? The fire at Hong Fuk Court—and similar tragedies like London’s 2017 Grenfell Tower fire—are harsh lessons for modern societies on managing high-density urban living.

The Hong Kong fire demonstrates clearly that the city—including its government—has not yet learned to manage such buildings safely. When officials treat victims’ questions as threats to national security, it shows an unwillingness to confront reality.

China’s rapid urbanization means cities across the mainland now resemble Hong Kong, sharing similar latent risks. Ensuring these skyscrapers are safe homes is also a pressing concern for the central government. I do not believe Beijing will ignore the lessons of this Hong Kong disaster or use “national security” as an excuse to bury the underlying problems; that would not benefit China either.

Recent developments suggest the central government may pursue accountability among Hong Kong officials. Perhaps, amid all the suffering, this is one small glimmer of hope for Hongkongers.

On 26 November 2025, a massive fire broke out at Wang Fuk Court in Tai Po, Hong Kong, during exterior wall renovation. Flames raced along the scaffolding and netting, igniting seven residential blocks at once. The blaze spread from one building to the entire estate in minutes. As of 2 December, the disaster had left 156 people dead and more than 30 missing, making it one of the deadliest residential fires in decades worldwide.

Caught between grief and fury, the public cannot help but ask:

Was this an accident, or a tragedy created by systemic failure?

A Disaster Rooted in Sheer Complacency

First-hand footage circulating online shows how quickly the fire spread. The primary cause was the use of non–fire-retardant scaffolding netting and foam panels. Under the Buildings Department and Labour Department’s guidelines, netting must be flame-retardant and self-extinguish within three seconds of ignition. But the netting seen on-site shot up in flames immediately.

Investigations revealed an even more infuriating detail:

Some contractors did purchase compliant fire-retardant netting — but installed it only at the base of each building, replacing the rest with ordinary, non-compliant netting to save roughly HKD 20,000 (about 105,800 TWD). Additionally, foam boards were used to seal some unit windows, funneling flames directly into homes. These materials had long been prohibited, yet were still used simply because they were cheap.

What’s worse, this danger was no secret.

For years, watchdog groups warned the government about flammable netting. Since 2023, Civic Sight chairman Michael Poon had sent over 80 emails to authorities about unsafe scaffolding in various housing estates. In May 2025, he specifically named Wang Fuk Court as using suspiciously non-compliant netting — but letters to the Fire Services Department never received a formal reply.

Residents also lodged complaints to multiple departments, only to be told that officials had “checked the certificates” or that fire risks were “low,” with no further action taken.

Engineers note that government inspections focus mainly on whether the structure of the scaffolding is secure, not whether the materials are fire resistant — effectively outsourcing public safety to the industry’s “self-discipline.” With lax oversight, contractors adopted a “no one checks anyway” mindset that turned regulations into empty words.

Inside the fire zone, fire safety systems also failed. Automatic alarms, sprinklers, hydrants, and fire bells in the eight buildings were all found to be nonfunctional, depriving residents of early escape warnings. Some exits were clogged with debris. It took three and a half hours from the first report for the incident to be upgraded to a five-alarm fire — a delay that worsened casualties.

From flammable materials, to inadequate government oversight, to malfunctioning fire systems, every layer of failure stacked together.

Let’s be clear: This was a man-made disaster.

Who Bears Responsibility?

If this was a man-made tragedy, where exactly did the system fail?

Police have arrested 15 people on suspicion of manslaughter, including executives from the main contractor, consulting engineers, and subcontractors involved in scaffolding and façade work.

The incident has also sparked another controversy:

Were there political–business entanglements?

DAB Tai Po South district councilor Wong Pik-kiu served as an adviser to the Wang Fuk Court owners’ corporation from early 2024 to 2025. During her tenure, the corporation approved the renovation project. She allegedly lobbied owners door-to-door to support the works and pushed for multiple controversial decisions, including simultaneous works on multiple blocks — increasing both risk and cost.

A district councilor serving as an OC adviser is a highly sensitive overlap. Councillors are expected to act as neutral third parties safeguarding public interest, whereas OC advisers handle tenders, project monitoring, and major financial decisions. The dual role naturally raises questions of conflict of interest.

Whether the OC, councilor, and contractors engaged in collusion, dereliction of duty, or even corruption remains under investigation by the ICAC and police.

But the tragedy exposes deep structural issues in Hong Kong’s building management system, which is a clear warning sign for the OC mechanism.

The Wider Problem: Aging Buildings and Weak Oversight

Old-building maintenance is a territory-wide problem. Wang Fuk Court is not an isolated case.

In 2021, Hong Kong had 27,000 buildings over 30 years old. By 2046, the number will rise to 40,000. With aging buildings, major repairs, fire system upgrades, escape-route improvements, and structural checks are becoming increasingly urgent.

But most homeowners lack engineering knowledge and rely entirely on their owners’ corporations. OC committee members are volunteers with limited time and expertise. Under pressure from mandatory inspection deadlines, they often make poor decisions with incomplete information.

Meanwhile, OCs hold enormous power — they manage all repair funds and approve all works — yet face minimal oversight. Bid-rigging and collusion are widespread.

Classic tactics involve competitors privately agreeing who should “win” a tender, distorting competition and harming owners.

Although Wang Fuk Court’s repair fund was managed by the OC, the Housing Bureau — overseer of subsidized housing — also cannot escape blame. With massive project costs and questionable workmanship, why did authorities not intervene or conduct deeper audits?

These systemic gaps enable problems to repeat endlessly.

How Australia Handles Major Repairs and Tendering

In contrast to Hong Kong’s volunteer-run OC model, Australia’s strata property system uses professional management + statutory regulation.

Owners corporations hire licensed strata managers, who then appoint independent building consultants to assess required works. Tendering follows a transparent, standardized process that includes checking contractor licences, insurance, and track records.

Owners rarely deal directly with contractors, reducing information asymmetry and the risk of lobbying. Major expenses must be approved by the owners’ meeting, and strata managers must provide written reports and bear legal accountability.

This creates clear divisions of responsibility, heightens transparency, and minimizes corruption, bid-rigging, and low-quality work. Contractors have fewer opportunities to privately lobby homeowners or manipulate the tendering process.

Is the Government Truly Responding to Public Demands?

After the disaster was widely recognized as man-made, public anger exploded.

Residents, experts, scholars, and former officials all condemned the failure of Hong Kong’s regulatory system and demanded accountability.

Residents quickly formed the Tai Po Wang Fuk Court Fire Concern Group, raising four demands on 28 November:

-

Ensure proper rehousing for affected residents

-

Establish an independent commission of inquiry

-

Conduct a comprehensive review of major-repairs regulations

-

Hold departments accountable for oversight failures

Over 5,000 online signatures were collected the next day.

Under intense public pressure, Chief Executive John Lee announced on 3 December the formation of an “independent committee” led by a judge to examine the fire and its rapid spread.

However — and this is crucial — this body is not a statutory Commission of Inquiry.

A COI, established under the Commissions of Inquiry Ordinance, has legal powers to summon witnesses, demand documents, and take sworn testimony, giving it far stronger investigative and accountability capabilities.

By comparison, the “independent committee” lacks compulsory powers and focuses on “review and prevention” rather than defining responsibility or recommending disciplinary action.

This falls far short of public expectations, raising doubts about whether the government genuinely intends to confront the issue.

A Second Fire: The Fire of Distrust

In the aftermath of the Wang Fuk Court inferno, the community displayed remarkable self-organisation: residents gathered supplies, assisted displaced families, compiled lists of elderly neighbours, and coordinated temporary support. These actions were the natural response of civil society stepping in when public governance collapses. And while contractor negligence and construction issues sparked public outrage, an even deeper anger targeted the government’s total failure in oversight and crisis management.

Ironically, as residents were busy helping one another, some volunteers were arrested on suspicion of “incitement.” The fire broke out just days before the 7 December Legislative Council election. In the eyes of the government, any form of spontaneous community mobilisation seemed to be viewed as a “risk” rather than support.

Haunted by the shadow of 2019, the authorities remain terrified of bottom-up community organising. Instead of crisis management, they engage in risk suppression—focusing on dampening social sentiment rather than improving rescue efficiency. Blame is shifted toward “those who raise questions,” instead of the systems that produced the problem in the first place.

These reactions transformed what could have been a moment of community unity into a much deeper crisis of public trust.

Beijing’s Disaster Narrative

In sharp contrast to the Hong Kong government’s understated approach, Beijing intervened swiftly and publicly. President Xi Jinping ordered full rescue efforts and expressed condolences immediately. Yet such speed also suggests that Beijing vividly remembers the 2022 Urumqi fire, which triggered the “White Paper Movement.”

In Chinese political logic, fires are never just accidents—they can become flashpoints of public anger. With long-standing grievances over housing policy, old-building safety, and the culture of unaccountability, Beijing moved quickly to prevent emotions from spilling over.

Notably, the Office for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong issued a statement during the rescue phase, warning that “anti-China, destabilising forces are waiting to create chaos,” emphasising that political stability overrides everything else.

Under China’s crisis-management style, officials frequently shift public focus from “the causes and responsibility of the disaster” toward “the hardship and heroism of rescue workers.” Following the Wang Fuk Court fire, some local media began flooding the airwaves with stories of brave firefighters and tireless medical staff, all being positive narratives that subtly eclipse the underlying issues of flammable materials, broken systems, and weak oversight.

By swiftly arresting a few contractors and engineers, authorities aim to frame the incident as the fault of several “technical offenders,” preventing accountability from extending to systemic failures or government departments.

This narrative reframes a man-made tragedy into a supposed showcase of “government mobilisation,” diluting public scrutiny and preventing grief and anger from evolving into collective resistance.

A particularly important detail:

In the early stages, several Western media outlets focused heavily on the idea that “bamboo scaffolding is inherently risky,” while barely discussing the scaffolding netting, material quality, or regulatory negligence. This inadvertently echoed the Hong Kong government’s early narrative frame. It also exposed a cultural bias—an assumption that bamboo equals danger—overlooking the rigorous safety standards of Hong Kong’s traditional scaffolding industry. As a result, some international reporting unintentionally helped divert attention away from structural, institutional failures during the crucial first days.

Who Should Be Held Accountable?

The shock of this catastrophe lies not only in the scale of casualties but in the fact that behind what seems like an “accident” are layers of systemic failure—from flammable netting and dead fire-safety systems, to weak regulation, chaotic building management, bid-rigging culture, and the government’s post-disaster reliance on a national-security framework to manage public sentiment.

So, the fundamental question remains:

Who is responsible for this fire?

As of the copy deadline (3 December) and after the seven-day mourning period, Hong Kong has seen zero officials, zero government departments, and zero senior leaders take any responsibility. Whether this was an accident or a man-made disaster is beyond obvious, yet the government—obsessed with saving face—refuses to admit regulatory failure. Instead, it blames bamboo and a handful of contractors, shrinking a deeply interconnected man-made catastrophe into the fault of a few convenient scapegoats.

AFP put it bluntly when a reporter asked Chief Executive John Lee:

“You said you want to lead Hong Kong from stability to prosperity.

But in this ‘prosperous’ society you described, 151 people have died in a single fire.

Why do you still deserve to keep your job?”

From 2019, to the pandemic, to the collapse of the medical system, and now this fire—no one has ever been held accountable for catastrophic policy failures.

What Can We Do?

The disaster is far from over. The real challenges are only beginning: nearly 2,000 households across the eight blocks face long-term displacement, trauma, and the struggle to rebuild their lives.

For Hongkongers and Chinese people living in Australia, what can be done?

Perhaps the answer is simpler—and more important—than we think:

Support those affected. Emotionally, psychologically, and materially. Even from afar, offering solidarity, sharing information, donating to practical assistance, or simply staying engaged with the issue matters.

After a tragedy like this, our role is not only to mourn.

It is to refuse to let the disaster fade away without accountability or reform.

And it is to remind ourselves, gently but urgently:

cherish the people beside us, and hold close those who still walk this uncertain world with us.

Listen Now

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

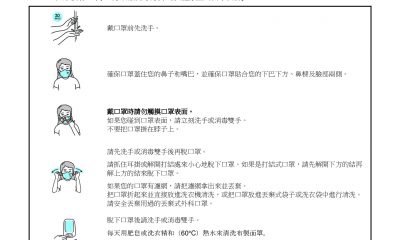

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單