The Delta variant of the coronavirus is estimated to be 40 per cent more transmissible than the Alpha variant that caused the last wave of infections in the UK, Britain’s Health Secretary says.

The Delta variant, also known as the Indian variant, is now the dominant strain in the UK, according to Public Health England figures.

It was the Alpha variant, previously known as the Kent variant, that forced the UK into lockdown in January.

The Delta variant is the same strain detected in Melbourne, but it has not been linked to the rest of Victoria’s outbreak.

Concerns are mounting over whether the emergence of the Delta variant threatens the UK government’s provisional June 21 deadline for lifting virus restrictions.

/Secretary of State for Health of the United Kingdom,Matt Hancock

Mr Hancock acknowledged that the Delta variant “does make the calculation more difficult for June 21”.

“We’ll look at the data for another week and then make a judgement,” he told the BBC on Sunday, stressing that the government was “absolutely open” to delaying the lifting of restrictions.

The secretary nevertheless stressed that those who have had two doses of vaccine should be protected against illness from the Delta variant.

Public Health England said last month that research showed double vaccination was similarly effective against both the Kent and Delta variants.

“The best scientific advice I have at this stage is that, after one jab, it’s not quite as effective against the new Delta variant, but after both jabs, it is,” Mr Hancock told the BBC.

So far hospitalisations are “broadly flat”, with very few hospitalised after receiving both vaccine doses, he added.

The UK has so far given more than 27 million people two doses — more than 50 percent of adults — while more than 40 million have had one dose.

Pregnant women and people in their 30s are being offered the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines where possible because of concerns about the risk of rare blood clots.

Why some variants more contagious than others?

The virus that causes COVID-19 is evolving, with new and more infectious variants taking hold.

But what makes this outbreak different from others is the spread of a “highly infectious” variant that was first detected in India in October last year.

There are currently four coronavirus variants of global concern that have been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO), each first detected in India, Brazil, South Africa and the UK.

Authorities in Vietnam have also identified a “dangerous” new hybrid variant that is a mix of the types first detected in the UK and India.

But how do these variants occur and what makes some more contagious than others?

What are variants?

The SARS-CoV-2 virus genome is made up of almost 30,000 nucleotides — molecules that contain instructions for the amino acids that make up its proteins.

When the virus infects a cell, it generates thousands of copies of itself and sometimes makes errors in the process.

Most of these mistakes — or mutations — are harmless and don’t lead to huge changes in how the virus infects and spreads through the population.

But sometimes these genetic changes can help the virus stay one step ahead, leading to variants that are more contagious and easily spread.

Why are they more contagious?

Mutations can lead to changes in any part of the virus, but tweaks in its spike proteins are the changes researchers are most concerned about.

These spike proteins help the virus latch onto and invade the cells of its host.

Variants with significant mutations in their spike proteins are listed as “variants of concern” by WHO, as they are associated with increased transmissibility and severity, and could have an impact on immunity.

The B.1.617 variant that was first detected in India has two defining mutations in its spike protein: E484Q and L452R.

These mutations help the virus infect cells more easily and dodge the immune system’s antibody response.

The B.1.617.1 sub-lineage of the Indian variant — also known as Kappa — that is circulating in Victoria has an additional mutation in its spike protein called Q1071H.

The more infectious B.1.617.2 sub-lineage that is surging in the UK — also known as Delta — contains more mutations in its spike protein, but lacks the E484Q mutation found in Kappa.

Instead, it has T478K, another mutation that has been associated with high infection rates, particularly in Mexico and the United States.

Delta is up to 50 per cent more transmissible than the B.1.1.7 variant — also called Alpha — first identified in the UK in December last year, Professor MacIntyre said.

While spike mutations have gained the spotlight, other mutations may also give SARS-CoV-2 variants an advantage.

Other errors in the genetic sequence can help the virus make more copies of itself inside human cells.

While it’s difficult to predict how many new SARS-CoV-2 variants we can expect to see in future, one thing’s for sure: the virus, like all pathogens, will continue to evolve.

The more the virus spreads, the more it has a chance to mutate into more contagious variants

In other words, the more people the virus infects, the greater chance it has of acquiring a mutation that gives it an advantage.

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years ago

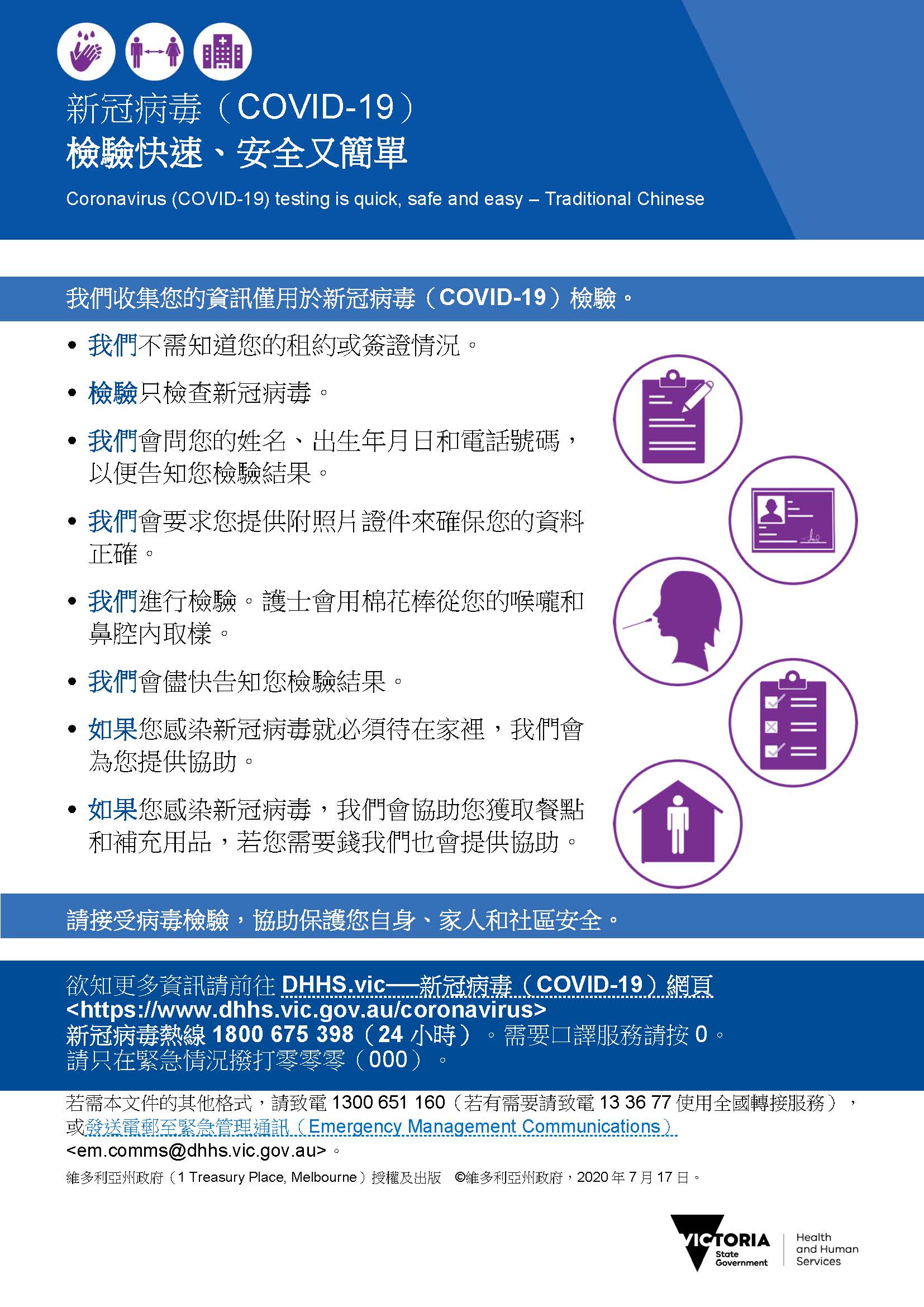

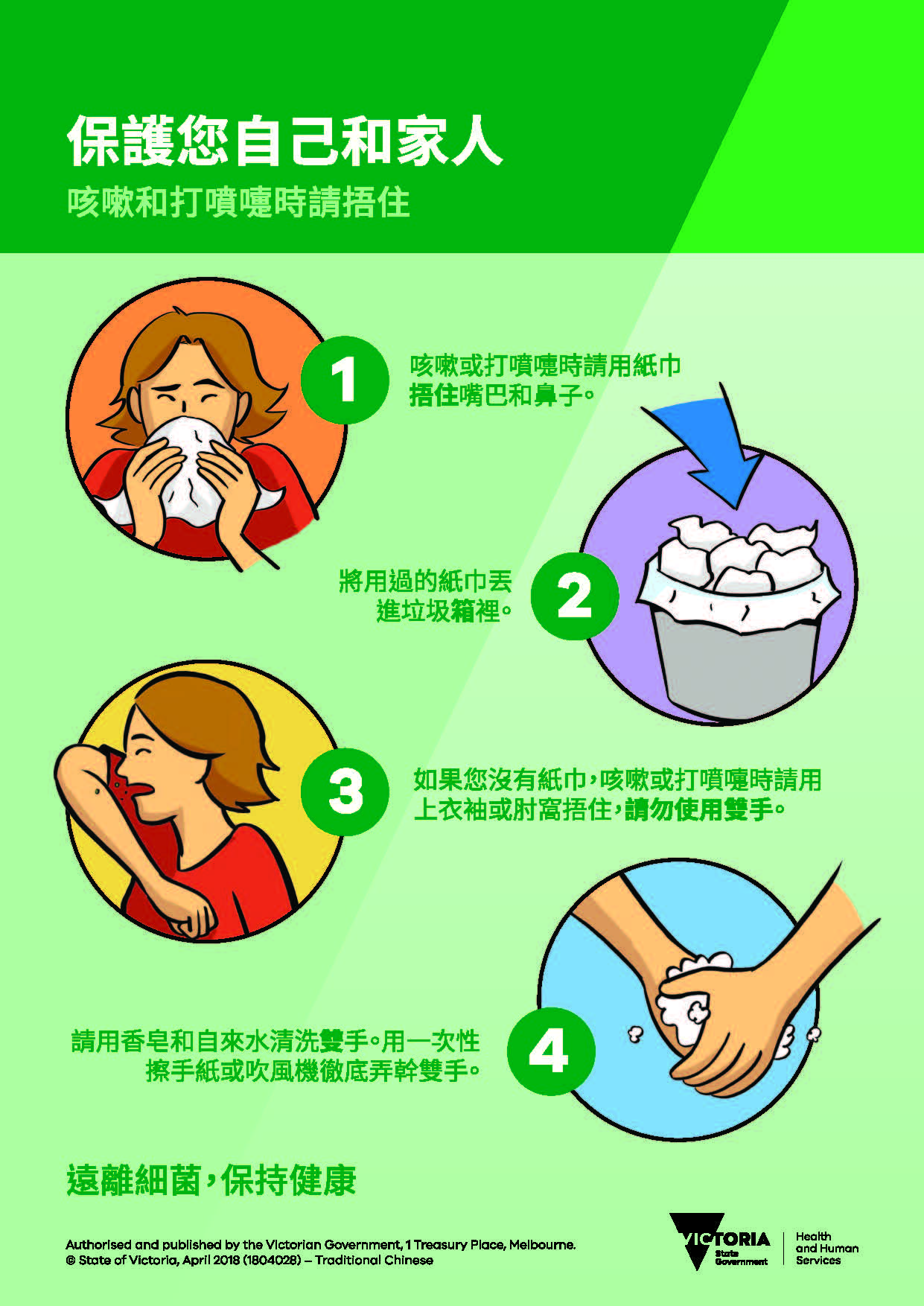

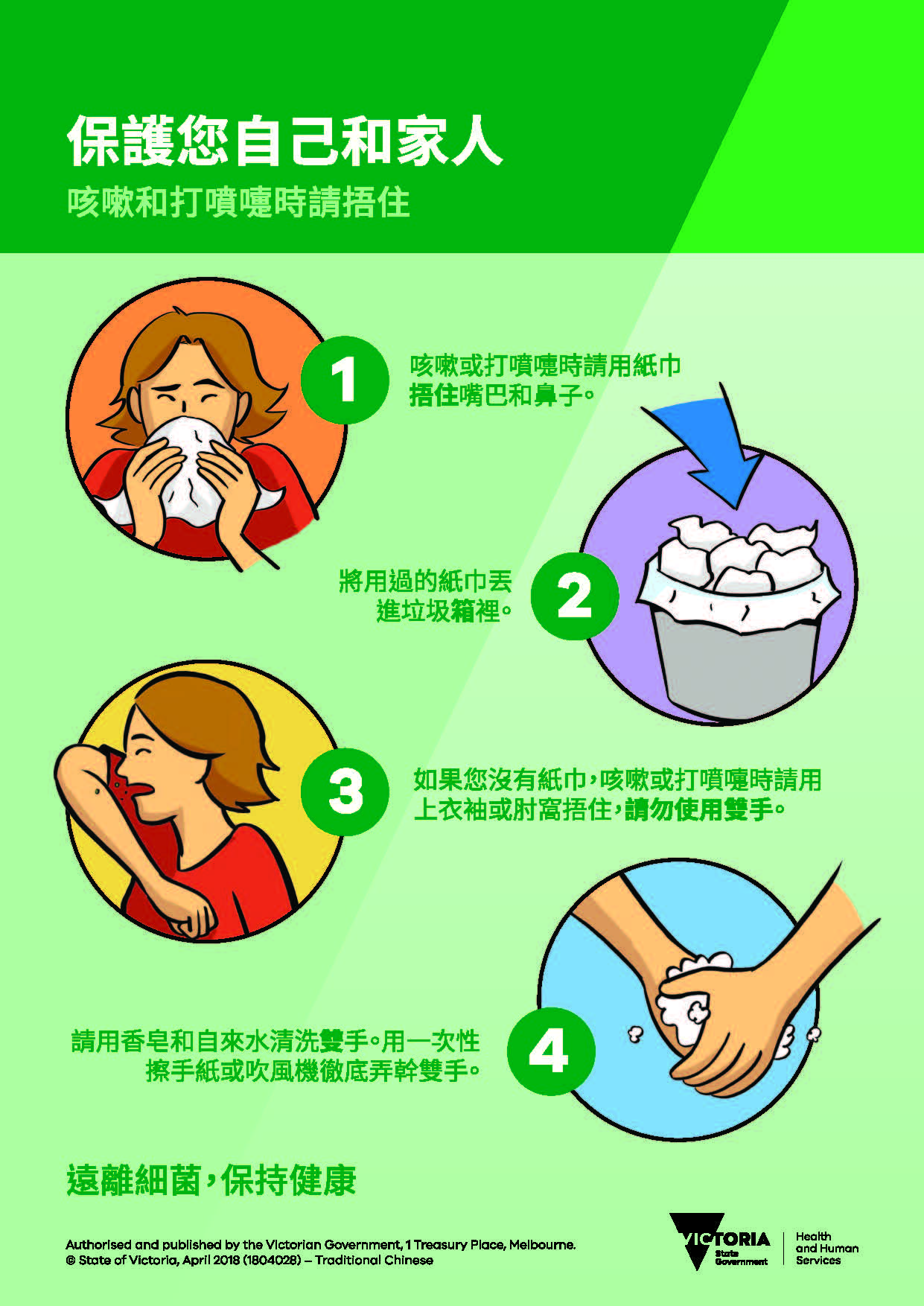

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago

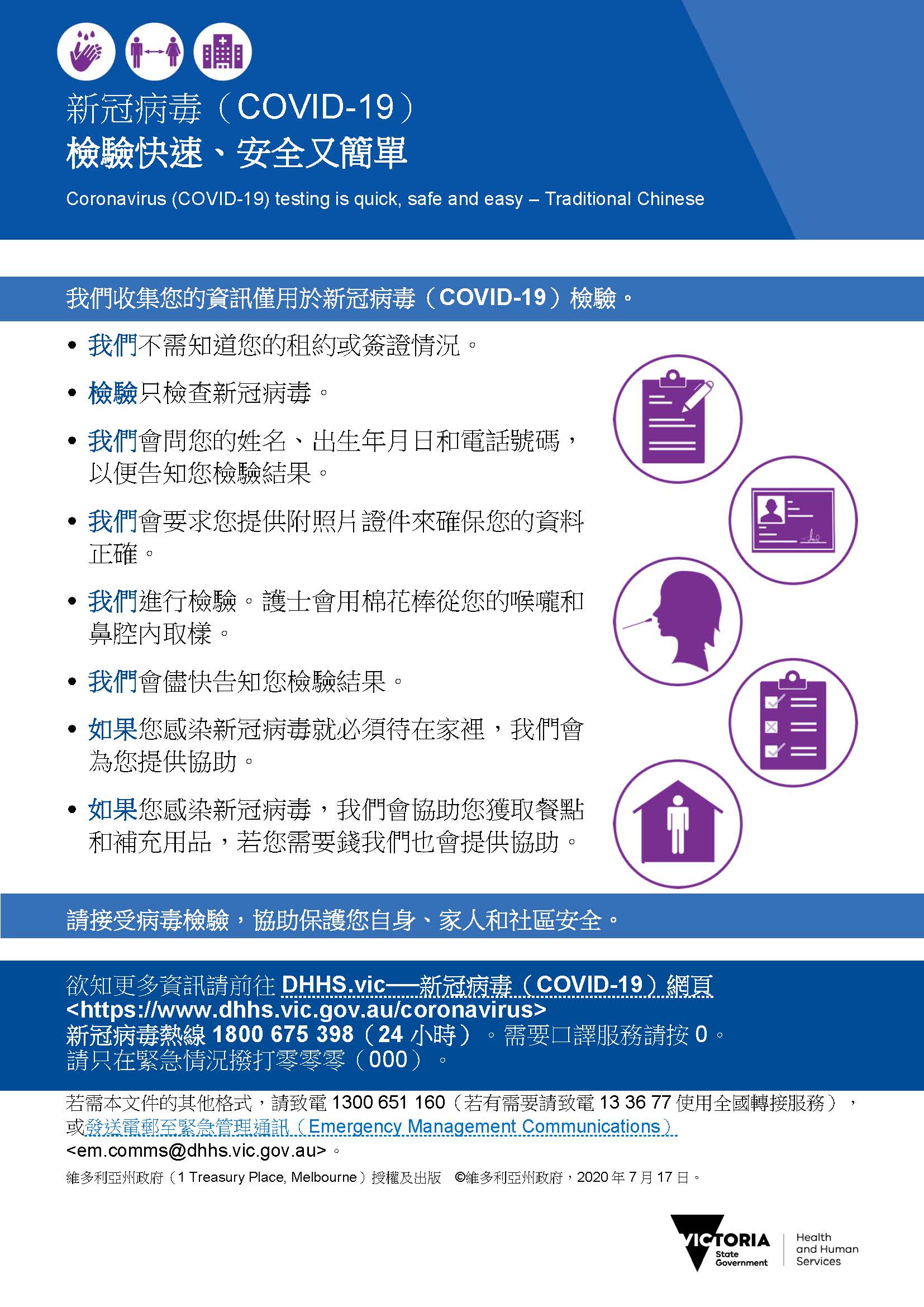

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago