Features

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Published

4 months agoon

Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan embarked on her first visit to China since taking office, from September 14 to 19, lasting five days. Her itinerary included Beijing, Shanghai, as well as Victoria’s sister cities Nanjing, Chengdu, and Deyang. Accompanied by Labor MPs, she met with Chinese officials and business leaders. The focus was on boosting trade, promoting education exchanges, expanding the tourism market, and attracting more Chinese students and investment, with the aim of raising Victoria’s profile in China.

Is Victoria’s Relationship with China Over?

China has long been Victoria’s largest trading partner and the main source of international visitors. Allan’s office framed this trip as “the beginning of a new golden era” and emphasized that the purpose was to rebuild friendship with China.

Looking back, former premier Daniel Andrews had strongly promoted cooperation with China and even signed the “Belt and Road” agreement in 2018. However, the federal government later exercised its power under the Foreign Arrangements Scheme Act for the first time, canceling two agreements Victoria signed with China, citing inconsistency with Australia’s foreign policy or harm to foreign relations. This move provoked strong dissatisfaction from Beijing, with China’s Foreign Ministry harshly criticizing Australia for having “no sincerity in improving China–Australia relations.”

Subsequently, relations between China and Australia deteriorated further due to multiple controversies. Australia criticized Beijing’s actions regarding Hong Kong protests and human rights issues in Xinjiang, and supported the World Health Organization’s independent investigation into the COVID-19 outbreak. Meanwhile, Australian intelligence agencies exposed China’s attempts to influence local politics through political donations, sparking national security concerns. These events further strained bilateral ties.

Even so, Victoria tried to maintain exchanges with China, establishing sister-city relationships with several Chinese cities and consolidating ties through education and business cooperation, attempting to preserve collaboration within an otherwise tense climate.

But compared with Andrews’ “pro-China” image, Allan faces a more delicate situation. After stepping down two years ago, Andrews turned to private business, becoming a consultant with close links to Chinese enterprises. More recently, he even appeared at a military parade in Tiananmen Square and was photographed with President Xi Jinping and other Chinese leaders, sparking controversy. As the current premier, Allan has said, “”Victoria is an old friend of China and these connections are so valuable for our state,” but she must strike a far more cautious balance between cooperation with China and domestic political sentiment.

Judging by the arrangements of this visit, China’s reception of Allan was clearly not on par with that of Andrews in the past. She only met with Minister of Education Huai Jinpeng, and her first policy speech was held merely at a hotel. This treatment was far less prestigious than Andrews’ high-level invitation to witness the Tiananmen parade just a week earlier. Observers speculate that Beijing attaches limited importance to the current Victorian government, possibly because the “Belt and Road” agreements were overturned by the federal government, or due to the broader backdrop of strained China–Australia relations.

The Contradictions of Education Diplomacy

One major highlight of this trip was to deepen education cooperation. In its newly released Victoria’s China Strategy: For a New Golden Era, the Victorian government pointed out that in 2024 the international education industry contributed as much as AUD 15.9 billion to the state’s economy, remaining Victoria’s largest service export for more than two decades. Among this, Chinese students numbered 64,000, making China the largest source country. The document listed “continue to strengthen our reputation as a preferred destination for Chinese visitors, students, researchers, and investors” as a strategic priority, emphasizing the need to further consolidate Victoria’s image as a global destination for Chinese tourists, students, researchers, and investors.

When meeting Chinese Education Minister Huai Jinpeng in Beijing, Allan repeatedly stressed Victoria’s welcoming attitude toward Chinese students, hoping to expand bilateral exchanges through stronger educational cooperation and demonstrating the importance she attaches to “education diplomacy.”

However, this proactive approach sharply contrasts with federal policy. In August 2025, the Australian federal government announced a new student quota system, capping the total number of international students nationwide at 295,000 in 2026. Although this figure was 25,000 higher than the current year, industry insiders believe that due to persistent restrictions in the immigration system, actual numbers are unlikely to reach the cap. This runs counter to Victoria’s slogan of “saying yes to international students,” revealing a clear policy gap between the state and federal levels.

Under this contradictory framework, Victoria’s efforts to deepen cooperation with China through education remain constrained by federal policy, making it difficult for the state to achieve significant breakthroughs on its own. With the failed Belt and Road experience still fresh, it is understandable why Beijing did not devote much attention to the current premier. Against this backdrop, Allan could only meet with China’s education minister, raising doubts about how much real progress could be made.

Underwhelming Economic and Trade Outcomes

Just as politics offered little warmth, business results also proved lackluster. Many expected one of Allan’s key goals would be to seek Chinese funding for the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL) project, which faces a massive AUD 34 billion funding shortfall. This expectation was heightened by the fact that the rail line runs through electorates represented by several members of the delegation.

Yet, only a handful of business meetings were reported, with few major corporations participating. The visible results amounted to just two announcements: a solar energy cooperation project at the beginning of the trip, and at the end, the purchase of four tunnel boring machines (TBMs) from Chinese manufacturers for the SRL project.

The former was limited in scale and faced local criticism—during construction the project would create only about 60 temporary jobs, and after completion just six permanent positions, with minimal local employment benefits and potential environmental impacts.

The latter, although Allan made a point of visiting tunnel works in Deyang, Sichuan, and staged photo opportunities to emphasize Victoria’s cooperation with China, was essentially “spending money on imports.” While buying Chinese TBMs secured equipment for the SRL, it raised questions: why not develop or support such technology domestically, creating local jobs and industries, instead of sending huge sums abroad?

In other words, these arrangements mostly involved one-way capital outflow, without bringing in real foreign investment or capital inflows. The outcomes fell short of expectations for “attracting Chinese investment,” leaving only purchases and symbolic cooperation. With political recognition lacking and economic results unimpressive, what substantive benefits did this trip actually deliver for Victoria’s economy?

Economic Diplomacy or Electioneering?

For Allan, the trip was something of a dilemma. As premier, she could not avoid going to China during her term. But at the same time, she surely knew it would be hard to achieve real breakthroughs. The result was like a salesman being ignored despite enthusiasm, or a poor relative knocking on doors only to be turned away. Why, then, did Allan still lead a high-profile delegation to China?

Funded by taxpayers at an estimated cost of several hundred thousand dollars, the delegation did not include a single minister—only MPs from electorates with large Chinese or multicultural populations. They included Parliamentary Secretary and Box Hill MP Paul Hamer, and four Labor backbenchers: Meng Heang Tak (Clarinda), Mathew Hilakari (Point Cook), Matt Fregon (Ashwood), and John Mullahy (Glen Waverley).

According to the 2021 census, Victoria has around 500,000 residents of Chinese descent, a significant share of the state’s 7 million population. In these key electorates, Chinese voters number in the tens of thousands, enough to influence electoral outcomes. While these accompanying MPs may have little policy influence, they are politically important. This raises questions over whether Allan’s visit was more about connecting with the Chinese community ahead of the November 2026 state election, consolidating a large and crucial voter bloc. Rather than an economic diplomacy mission, it may have been a campaign-style political tour.

The trip delivered limited results, with symbolism outweighing substance. Allan brought back no new investment and no major corporate commitments, while her accompanying MPs became the focus. What can these powerless backbenchers actually bring to Victoria? Do they signal attention to multicultural communities and bolster diplomatic credentials? Or was this merely a “taxpayer-funded election show,” with taxpayer money spent on photo ops in China to build momentum for the next election? Anyone with a bit of political sense can see through it.

Multicultural Development

Just before the trip, the Victorian government released the Victoria’s Multicultural Review, regarded as the most significant policy reform in decades. Led by George Lekakis AO and an expert advisory group, it drew on 57 community meetings, consultations with over 640 residents, and input from more than 150 organizations and community groups. The goal was to strengthen social cohesion and rebuild trust between the government and multicultural communities. The report was released on September 11 by Allan and Minister for Multicultural Affairs Ingrid Stitt.

Core recommendations include establishing a new statutory agency, Multicultural Victoria, headed by a Multicultural Coordinator General, supported by two deputies (one from a rural area), and advised by a five-member commissioner panel. This structure would replace the largely ceremonial Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC), which for years was limited to public relations without significant policy impact.

Following the review’s release, Allan quickly linked “multiculturalism” with the Chinese community. On September 12, in her hometown Bendigo, she announced nearly AUD 400,000 in funding to upgrade the Golden Dragon Museum into the “National Chinese Museum of Australia.” This symbolic move not only highlighted Bendigo’s historical ties to Chinese immigrants during the gold rush but also aimed to strengthen the cultural status of the Chinese community in Victoria.

Other funded projects included the Mingyue Buddhist Temple in Springvale South, the Avalokiteshvara Yuan Tong Monastery underground car park in Deer Park, the Museum of Chinese Australian History in Melbourne CBD, and infrastructure and lighting upgrades at the Chinese Association of Victoria Inc in Wantirna. These investments enhance cultural facilities and directly address community needs.

Is Multiculturalism a Political Tool or Genuine Goal?

This raises the question: are Allan’s initiatives genuinely aimed at fostering social cohesion, or are they part of political calculation? Victoria has long led the country in multicultural policy, but its political functions are also significant. During Andrews’ era, “multiculturalism” was used to package economic cooperation with China, drawing criticism of “national security risks” and “overdependence.” Allan now continues this approach but faces cool responses from Beijing and skepticism from the opposition and media at home.

Still, Allan’s strategy is not identical to Andrews’. Unlike the 2016 version of the “China Strategy,” her policy no longer emphasizes export figures or the economic benefits of the Belt and Road, but instead focuses more on cultural exchange and community engagement, encouraging Chinese-Australians to actively shape interactions with China. This shift highlights interpersonal and cultural connections rather than purely commercial transactions.

She has repeatedly wrapped her policies in “personal stories”: from Beijing to Nanjing to Shanghai, she promoted not just Victoria’s universities, tourism, and agricultural products, but also the importance of shared history, language, and culture. When meeting Education Minister Huai Jinpeng, she mentioned that her 13-year-old daughter is learning Chinese, to foster relatability.

Thus, Allan’s “multicultural strategy” carries two possible meanings: on one hand, it shows a sincere wish to improve social cohesion and strengthen ties with the Chinese community; on the other hand, it inevitably serves political calculation and election mobilization. As the 2026 state election approaches, Allan’s ability to convince both the Chinese community and the broader electorate that this is more than just political maneuvering but a genuine social vision will be a critical test of her leadership.

Still Unresolved: Practical Needs of Multicultural Communities

Even if Allan today offers small grants or gestures of goodwill toward the Chinese community, they pale in comparison to Andrews’ campaign promises in 2014 and 2018, when he pledged nearly AUD 20 million for the Chinese and Indian communities to purchase land for building aged care facilities. These two groups are now Victoria’s largest multicultural communities, and both place high cultural importance on caring for elders. Whether the elderly receive proper care in later life is a vital issue.

In 2018, the Australian government noted that as people live longer, the number of dementia patients is surging. For non-English-speaking elderly migrants—many of whom either never learned English or lose it due to dementia—the need for care in their native language and cultural context is especially acute. Yet mainstream services remain unwilling to provide such care. Therefore, the government has a responsibility to help minority communities build appropriate aged care facilities. Andrews recognized this situation and made it a campaign pledge.

But to this day, the Victorian government has only “purchased” the land and has not handed it over to community groups to build facilities—an 11-year failure that could be seen as the biggest “betrayal” of minority communities in Victorian history. By appealing to immigrant communities that value elder care, Andrews gained their votes to govern Victoria, but apparently never intended to deliver on his promises. It was a shameless act. Yet after Allan took over, she did not address the issue. Worse, last year she changed project rules, stripping Chinese and Indian community organizations of eligibility to apply to build aged care homes.

Clearly, the Allan government’s actions today sharply contradict its rhetoric about promoting multicultural development. This is likely to become a key concern for multicultural community voters in next year’s state election.

You may like

Raymond Chow

My New Challenge

Over the past few decades, I’ve written numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics. However, last October, I decided to write a book entirely different from anything I had done before, titled Solitary but Not Isolated. I chose to publish it through crowdfunding. Readers interested in supporting this book can visit the following webpage to learn more and help make it a reality.

I attended a rooftop school in Hong Kong for primary education (a unique feature of Hong Kong in the 1960s: temporary classrooms built on top of apartment blocks in resettlement areas to accommodate children who had moved into the district). Resources were extremely limited. In sixth grade, the school principal gave me and seven other students the opportunity to post our writings on the bulletin board every two weeks for the whole school to read. This was my first experience of writing for a public audience.

In secondary school at Queen’s College, the school published the annual magazine The Yellow Dragon, the earliest and longest-running secondary school annual in Hong Kong. My writings were never published there, though my photos occasionally appeared in reports of school activities. At university, I volunteered as editor for a scholarly publication by the Science Society called Exploration, but after two or three years it was discontinued as no one wished to continue it.

During university, I studied mathematics, which required little essay writing—mostly problem-solving. After entering the field of education, I wrote numerous articles on Hong Kong education that were published in newspaper columns. Later, through curriculum development and teacher training in Hong Kong, I had the rare opportunity to write and publish mathematics textbooks spanning from Grade 1 to Form 7—something unprecedented in Hong Kong.

After moving to Australia, I served as editor of the Christian publication Living Monthly, and eventually founded Sameway magazine, which continues today. From the first issue, I wrote the opening column Words of Sameway, and over 21 years, I have written a total of 745 pieces—a record of my life.

Yet writing Solitary but Not Isolated is something I never anticipated doing since I first learned about autism decades ago. Publishing this book is closely connected to my work with Sameway. I can only say this is a new challenge given by God, a chance to take Sameway to a new stage.

Those Who Love Solitude

Solitary but Not Isolated tells the story of a person with autism. Based on her experiences, the Happy Hands Organization has developed a bilingual training program to help autistic individuals transition from school to the workplace. Launched this year, the program aims to support others in similar circumstances.

Most people with autism do not actively seek social interactions. When they do engage with strangers, they may appear difficult to connect with or communicate with, often leading to social neglect or isolation. For parents and family, this creates a lifelong burden. Even those who complete secondary or tertiary education, despite having professional knowledge, often cannot fully utilize their abilities at work because of incomplete social understanding and lack of basic communication skills. Consequently, they are frequently relegated to jobs that do not match their abilities or are assigned work requiring minimal interaction.

Western society’s understanding of autism began with the lifestyle demands of modern life, emphasizing early social engagement and learning in school. Families, having fewer children, often pay close attention to each child’s development and have higher expectations. Over the decades, understanding of autism has evolved—from viewing it as a mental illness to recognizing it as a deviation from typical personality development. Yet how society should assist their growth remains uncertain.

Decades ago, Western focus was on “treating” autism. Research into genetic, environmental, or physical causes has made limited progress. Interventions to change solitary behaviors are also limited—for example, providing speech therapy in childhood or occupational therapy for daily living skills offers only partial support. While societal acceptance and support for autistic individuals have greatly increased, parents feel that more is needed when their children enter adult life and the workforce.

In short, those inclined toward solitude still face a gap in having equal opportunities to thrive socially and professionally.

Understanding Society and the World

Many autistic individuals focus intensely on specific interests, with little experience in social relationships or current events. As adults, this often leads others to perceive them as unaware of society, or even “odd.” In workplaces, where collaboration is essential, they may face exclusion. Many end up in solitary work with minimal social interaction.

Among Chinese communities, first- or second-generation immigrants with autism often face compounded challenges due to limited knowledge of society. Parents, unfamiliar with Australian systems, cannot fully guide their children, and these high-ability individuals rarely integrate with society, limiting opportunities to demonstrate their potential.

In 2024, ABC launched The Assembly, a TV interview program where host Leigh Sales trained 15 autistic individuals to conduct interviews and produce the show. Participants significantly increased their understanding of society and the world, and their communication and social skills improved greatly.

Last year, Sameway had the opportunity to train a bilingual autistic new immigrant, successfully helping her become a magazine editor. Meanwhile, the Happy Hands Organization developed a workplace adaptation program for bilingual, high-functioning autistic individuals. Through four to six months of training, this program offers these often-overlooked individuals a chance to adapt and develop in Australia.

Thus, Sameway is not only an information platform supporting immigrant communities but also provides a development space and opportunities for those with special needs. Readers interested can contact our magazine or the Happy Hands Organization for details.

The Loneliness of Immigrants

Many immigrants arrive in Australia as adults. They often lack opportunities to understand society deeply and, due to work and life commitments, rarely have the time to engage fully with their new environment or develop close relationships with Australians. Consequently, most live within Chinese communities with similar backgrounds. Passive personalities or limited social skills often lead to intense feelings of loneliness.

Leaving their original home and social networks creates a sense of marginalization similar to that experienced by some autistic individuals. Many immigrants are willing to understand and engage with their new society but face personal limitations and a lack of proactive governmental support, leaving them unable to integrate fully into Australian life.

Chinese immigrants, in particular, may rely heavily on long-term Chinese social media and information platforms, further isolating them from the broader society. This social isolation significantly affects their participation and engagement in Australian life.

The goal of Sameway is to assist immigrants in integrating into Australia, fostering participation and engagement in society. We hope that with continued support, we can go further and achieve more.

During the Christmas and New Year period, “Sameway” relocated though only to a spot less than 100 meters across from their original office. It was a tiring task, but we have finally settled in, allowing us to take a longer break during the holiday.

However, the world still undergoes significant changes. The President of Venezuela has been forcibly taken to New York for trial, while the new leader of Venezuela is willing to govern in line with U.S. interests. The longstanding alliance between Europe and the U.S. has become history in light of the U.S. attempt to purchase Greenland. The “Board of Peace” established by Trump requests that nations place the keeping of global peace in his personal hands, but attendees at the invitation include authoritarian dictators who have initiated wars multiple times. The generation that has grown up advocating for global integration, respect for human rights, and peaceful coexistence is now at a lost and confused. Will the world revert to a chaotic state governed by the law of the jungle, where strong countries dominate weaker ones, or can humanity choose to move forward in civilization by learning mistakes from history? We truly have no sure answer.

However, it is a time where the rise of Trump and the increasing power of global far-right political forces, coupled with the internet and social media replacing traditional media as the main source of information for many people. This has led to a society overwhelmed with information and challenges in distinguishing truth from falsehood, which is equally as frightening as an era where information is blocked, preventing access to necessary knowledge.

In Australia, as a multicultural country, immigrants face significant difficulties in obtaining lifestyle information through mainstream media. I believe that to build Australia as a harmonious and cohesive society, the government must invest substantial resources to assist immigrant communities to establish high-quality and credible multicultural media, and to accelerate the integration of first-generation immigrants into society, allowing them to become a driving force in social development.

In the past year, we have strengthened the current affairs information provided on our website. In the coming year, we will focus on enhancing our information services for the Chinese community through our broadcasts and magazine publications. I hope you can support us in achieving the goal of promoting the development of the Chinese immigrant community.

Starting this year, in line with the REJOICE’s initiative for bilingual new immigrants with autism, I will be writing a brand-new column to explore this topic with the community as they navigate With the NDIS program. I hope this innovative program by the REJOICE will receive your support for promotion and development within the community.

Additionally, after three years of training aimed at encouraging seniors to use social platforms to expand their community engagement, we will take a further step this year by launching training courses to assist seniors in using artificial intelligence. Our goal is to help Chinese seniors in Australia stay up-to-date and enjoy a higher quality of life brought about by AI.

In the new year, let us work together to build a stronger local Chinese community.

Since January 20, 2025, when Trump assumed the U.S. presidency once again, domestic issues in America have been frequent and complex, but the world cannot deny that his foreign policy has reshaped the global political landscape, ushering in a new era.

Over the past year, Trump has been extremely proactive in foreign affairs—from Greenland to Venezuela—demonstrating relentless ambition to expand U.S. influence abroad, even amid controversy and the risk of destabilizing other nations.

Prelude to 2025

Let’s briefly review Trump’s major foreign policy actions in 2025.

First, his involvement in the Gaza Strip cannot be overlooked. In February 2025, he publicly stated that the U.S. would play a more active, even leading, role in the region, supporting Israel’s security needs, including strengthening border defense and intelligence sharing. He also attempted to broker ceasefire talks in the U.S.’s name, coordinating Egypt, Qatar, and other countries as intermediaries. By October, Trump personally attended a multilateral meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, pushing for a ceasefire agreement and reconstruction framework between Israel and Hamas.

While opinions on his approach were divided, with some critics arguing that direct intervention could heighten regional tensions, Trump nonetheless reaffirmed America’s influence and presence in Middle Eastern affairs.

Early in 2025, the Trump administration reviewed all foreign aid and temporarily halted military assistance to Ukraine, using it as leverage to push forward negotiations. By mid-March, following U.S.–Ukraine consultations, military and security support resumed, including air defense systems, drone technology, and financial assistance. The U.S. also advocated international sanctions against Russia, such as high-tech export restrictions and asset freezes. These actions demonstrated Trump’s support for strategic allies and further solidified U.S. influence in Europe.

While these events may seem unrelated, they set the stage for early 2026’s diplomatic developments.

The Venezuela Raid

Trump’s most notable action in January 2026 was the sudden capture (or abduction) of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife.

In fact, as early as December 1, 2025, Trump had called Maduro, demanding he step down. When Maduro refused, Trump publicly ramped up pressure in mid-to-late December, applying economic and military pressure—including blockades, intercepting suspicious ships, and bolstering military deployments—to isolate the Maduro government. He even hinted that further U.S. action might follow if Maduro continued to resist, signaling a preemptive warning.

The result: U.S. forces launched a large-scale operation codenamed “Absolute Determination”, storming Caracas, capturing Maduro and his wife, and transporting them to New York for trial. The justification cited Maduro and his inner circle’s involvement in drug trafficking and terrorism, including conspiracies to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. At the same time, Maduro’s government had close ties with China and Russia, who provided military and economic support, posing a threat to U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The operation was also seen as a move to block rival powers from gaining leverage in Venezuela. More importantly, given Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, Trump clearly aimed to reassert U.S. dominance in the hemisphere and secure economic benefits. For many Americans, the raid showcased U.S. military might, boosting Trump’s prestige and approval. True to form, Trump paid little attention to criticism, focusing instead on praise, and was visibly self-satisfied.

International reactions were strong. China and Russia immediately condemned the U.S. action, calling it a severe violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and international law. Iran and other nations with tense U.S. relations also criticized the operation as unilateralism under the guise of anti-drug and anti-terrorism efforts, destabilizing the region.

European responses were mixed. Some EU countries long critical of Maduro still expressed reservations about the U.S. bypassing international authorization for direct military action, emphasizing that even dealing with authoritarian regimes should follow international mechanisms. This tension revealed the strain Trump’s style places on traditional allies.

In Latin America, reactions were split: anti-Maduro governments and Venezuelan opposition privately supported the move as a chance to break political deadlock, while others feared overt U.S. military intervention might revive Cold War-era “Monroe Doctrine” fears, worsening regional security.

Currently, former Vice President Rodríguez serves as interim president of Venezuela, cooperating with the U.S. while maintaining loyalty to the domestic ruling class, keeping the country relatively stable. For Trump, the goal of preventing other powers from gaining influence in the Americas and securing economic gains was achieved. Many Americans saw the raid as a demonstration of military strength, reinforcing Trump’s image as a decisive leader.

Trump’s Greenland Gambit

Since 2025, Trump has repeatedly brought Greenland into the spotlight, making it one of the most challenging and controversial topics of his second term.

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is under Danish sovereignty but enjoys local autonomy. Its location between North America and Europe along the Arctic shipping route has made it strategically valuable. Previously overlooked due to extreme cold, climate change and melting ice have expanded Arctic navigation, increasing Greenland’s military and technological importance. The island also contains vast deposits of rare earth and critical minerals, essential for modern technology and defense systems.

Trump’s assertive approach clearly aimed to maximize U.S. influence over Greenland. In 2025, he publicly expressed interest in buying Greenland and urged negotiations to secure it, even hinting at military options. This escalated tensions with Denmark and Europe.

European reactions were unanimous: Greenlandic leaders stated the island is “not for sale”, and massive protests erupted in Greenland and Denmark. The UK prime minister warned Trump that high tariffs or aggression would be a grave mistake, while EU countries—including Denmark, France, Germany, and the UK—supported Danish sovereignty. Even European far-right parties, traditionally aligned with Trump, criticized his Greenland strategy as overt aggression, causing internal rifts.

At the 2026 Davos World Economic Forum, Trump and NATO Secretary-General Rutte reached a “preliminary framework” focusing on Arctic security cooperation rather than territorial control. Trump framed it as safeguarding U.S. military bases and economic interests, while Denmark retained final authority. However, Greenland’s government stressed it was not fully involved in negotiations, highlighting an ongoing tension. Analysts debate whether this is a tactical retreat or pragmatic compromise.

Even with the temporary easing of tensions, U.S.–Europe trust has been strained, showing how far-reaching Trump’s assertive diplomacy has become.

Iran Unrest and U.S. Pressure

From late December 2025, Iran experienced nationwide protests, initially triggered by economic collapse, currency devaluation, and skyrocketing living costs, evolving into broad dissatisfaction with the regime. The government’s harsh crackdown led to casualties and arrests on a scale unseen since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The U.S., which maintains heavy sanctions against Iran citing terrorism sponsorship and nuclear/military threats, seized this moment to intervene. Trump publicly announced deploying a fleet—including aircraft carriers and missile destroyers—to the Persian Gulf to deter further escalation. He emphasized a preference for avoiding force but warned of potential military action if the regime continued violent repression.

Trump also communicated with Iranian protesters via public statements and social media, encouraging demonstrations and denouncing government violence. He canceled all official diplomatic talks until Tehran ceased the crackdown. While some protesters hoped for U.S. support, the absence of direct action led to frustration and feelings of abandonment.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard leaders warned that any U.S. strike would be considered a full-scale war. Protests and anti-U.S. imagery reflected strong resistance. Intelligence reports indicating a temporary halt in state violence led Trump to consider pausing military actions while closely monitoring the situation, balancing threats with cautious observation.

Trump’s strategy combined military presence and public warnings to pressure Tehran, deter large-scale killings, and strengthen U.S. influence in the Middle East. Yet this high-risk approach also raised the possibility of miscalculations, where tensions could escalate unintentionally, making the U.S. a target for criticism and resistance.

The “Board of Peace”

Traditionally, the U.S. has been seen as the global big brother. But with China’s growing influence and global economic support programs, U.S. presidents often feel impatient with Beijing’s increasing UN sway. Trump, ambitious and assertive, sought to take matters further.

At the 2026 Davos Forum, he launched the “Board of Peace”, initially proposed to address Gaza peace but now expanded to serve as a broader global conflict mediation mechanism. The initiative leverages U.S. influence to create an alternative diplomatic platform and invites multiple countries to participate.

However, critics question whether it is more for show than genuine peacekeeping. The EU’s concern lies less with the stated goals and more with the lack of clarity: the legal status, decision-making process, funding, and international law accountability remain unspecified. Unlike multilateral bodies like the UN or OSCE, this U.S.-backed, president-driven mechanism risks becoming a coercive tool rather than a genuine mediator.

The EU fears it could undermine Europe’s long-standing role in Middle East diplomacy, forcing it from rule-maker to follower. China was excluded, reflecting Trump’s view of Beijing as a competitor, not a partner. The Board aims to present participation as a political statement, effectively creating a U.S.-led bloc in global conflict mediation.

For Australia, the Board is a hot potato. Prime Minister Albanese received an invitation but has not confirmed participation. Several NATO and EU countries have declined, while Canada was disinvited over disagreements on China policy. Thirty-plus leaders who accepted include war actors like Putin and Israel’s Netanyahu. How they could effectively promote peace remains questionable, and handling the invitation diplomatically will test Albanese’s political skill.

Trump’s Diplomatic Logic

Across Gaza, Ukraine, Venezuela, Greenland, Iran, and the Board of Peace, Trump’s strategy is consistent: proactive engagement, pressure, disruption of norms, and forcing allies and adversaries to recalculate. He eschews slow multilateral negotiations in favor of military, economic, and media leverage, coupled with highly personalized decision-making, shifting power quickly at the negotiating table.

To Trump, diplomacy is a continuous game of strategy, not merely maintaining order. He pushes situations to the edge, then retreats strategically to gain advantage. While controversial and eroding trust among allies, it successfully recenters U.S. influence.

Crucially, Trump applies pressure not only to adversaries but to allies, forcing them to demonstrate loyalty or strategic value. This increases U.S. bargaining leverage but consumes trust capital, making international relations more transactional and short-term, and setting the stage for future friction.

Costs and Risks of Assertive Diplomacy

Reliance on pressure and uncertainty may yield short-term results but risks long-term instability. Highly personalized, low-institutional approaches erode trust in rules, procedures, and multilateral cooperation. Misjudgments are more likely in opaque, high-stakes situations. Allies and adversaries may misread threats, escalating conflict even without provocation.

Trump is reshaping U.S. diplomacy from guardian of order to rewriter of order, providing tactical flexibility but weakening institutional credibility. Whether the U.S. can balance assertive pressure with sustained trust will determine its long-term global leadership.

Ultimately, Trump’s strategy may open new strategic space for the U.S. or provoke deeper backlash and confrontation. One thing is certain: the international stage in 2026 is no longer the old world, and Trump is the key variable driving this structural transformation.

Listen Now

Pro-Trump Brazilian Influencer Arrested by U.S. ICE

German Chancellor Merz Discusses “Shared Nuclear Umbrella” with European Allies

One Nation’s “Spot the Westerner” Video Condemned

Littleproud retains leadership, Sussan Ley’s position uncertain

Starmer suggests Prince Andrew testify to US Congress

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

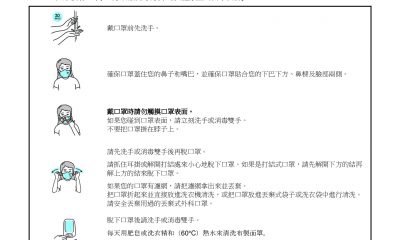

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized6 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單