Features

Sydney Church Attacks: A Warning

Published

2 years agoon

Article/Blessing CALD Editorial;Photo/Internet

19 mins audio

Following a terrified knife attack at a shopping center in Bondi Junction, Sydney, another knife attack at a church in West Sydney has shaken Australia. The incident has been characterized as a “terrorist act” and NSW Police Commissioner Karen Webb has confirmed that the teenager who was arrested after the knife attack at the church made comments during the incident suggesting that the attack was religiously motivated. This incident makes us reflect on how the government can better advocate for a more diverse, inclusive and safe society in the aftermath of this religious conflict. This is a difficult issue that Australia, as an immigrant society, will never be able to get around.

What made a teenager wield a knife?

On the evening of April 15, Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel was leading a service at Christ The Good Shepherd Church in Wakeley, west of Sydney, and streaming the service live online. Suddenly, a 16-year-old boy lunged at him with a knife, stabbing the bishop and injuring three other men. The four injured, aged between 20 and 60, are all in no danger of dying and are receiving medical treatment. Local police arrived quickly after the incident and arrested the teenager.

Bishop Mar Mari Emanuel is a prominent religious leader in the area. The conservative Assyrian leader is known for his outspoken views against the Covid pandemic , homosexuality, and non-Christian religions, including Judaism and Islam. And this is considered by many to be the main reason why he was targeted – because of his critical and outspoken views on Islam. Many of his sermons criticized the Quran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and attracted as many as 240,000 fans. The boy in question is said to have made comments in Arabic referring to insults against ‘my prophet’ before stabbing the bishop.

Investigators from the Sydney Joint Terrorism Unit (JTU) began questioning the teenager at the hospital last week and accused him of committing an act of terrorism. Terrorism is defined in federal law as an act or threat intended to “advance political, ideological or religious causes” and to “coerce or intimidate the government or public of Australia or a foreign country”. Terrorism is a generic term referring to allegations of terrorism, while a ‘terrorist act’ is a specific unlawful act that ’causes serious bodily harm to an individual or serious damage to property, causes death or endangers the life of an individual, poses a serious threat to public health and safety, or seriously interferes with, disrupts or disrupts an electronic information, telecommunications or financial system’, an offense punishable by up to life imprisonment. The teenager was refused bail and traveled to court from his hospital bed. The teenager, who allegedly used a knife that cut off one of his fingers, also underwent surgery. The Joint Terrorism Unit (JTU) is made up of members of NSW Police, the Australian Federal Police, the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO) and the NSW Criminal Investigation Commission (CIC).

The 16-year-old was expelled from a school in West Sydney six months ago after being diagnosed with anger management issues, being very withdrawn and spending long periods of time in his bedroom playing on his computer. His parents were appalled by his behavior and have not returned to their West Sydney home since the attack because they fear for their safety. Based on known information, it appears the teenager was acting alone at the time of the attack. Meanwhile, the head of the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO), Mike Burgess, added that Australia’s national terrorism threat level would remain at “likely”.

Crowds gather to cause riots

As the incident was being broadcast live on the internet, a demonstration broke out outside the church immediately after the incident, with people gathering to denounce the suspect. Some people shouted “bring him out” and “eye for an eye”, and police were forced to stay in the church with the suspect and at one point tear gas was used to disperse the crowd. More than 100 police officers were mobilized to deal with the riot that night. Many officers were injured, police cars were vandalized, and a large number of police officers and medical staff were forced to take refuge inside the church. Investigators are looking for up to 50 people who took part in the violence; three people have already appeared in court on charges of participating in the riot. Many of those involved in the riots were not members of the church community, and some simply came to participate in the riots, “which is shameful and disgusting. Prime Minister Albanese also issued a statement condemning the mass disorder, saying “it is unacceptable to obstruct and harm police officers in the performance of their duties.

The current online environment, particularly in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, has exacerbated tensions between the groups. West Sydney is a melting pot of different cultures from the Middle East, and the often complex relationships between groups can easily create a fertile environment for angry individuals who want to take action, target, or even be motivated to attack someone. After the attack, religious groups condemned the attack and called for calm.

Assyrian History

The incident took place in the Assyrian community. The Assyrians are a people of Near Eastern Mesopotamia, said to have originated from the city of Ashur, who took control of the Middle East in 824 BC, and in 671 BC, the Assyrian armies conquered Egypt and became the hegemonic powers of the world at that time, succeeding the Babylonian Empire. However, after the Persian, Greek and Roman empires had fallen into disrepute, the Assyrians lived only in the present-day regions of Syria and Iraq. However, started in 100 AD, the Assyrians converted to Christianity, so that Syria was a predominantly Christian country, while the Assyrian Christians lived in a country surrounded by Muslims for a long time. For more than 1,000 years, the Christians in Syria have lived under long term oppression, and many of them have migrated to different countries around the world. There are now 700,000 Assyrians in Syria and close to 600,000 Assyrians living in the United States. Stockholm, Sweden, and Fairfield, Sydney, have the largest Assyrian diaspora in terms of urban population.

The Assyrians were a dispossessed people for over a thousand years, and were subjected to various forms of oppression under various rulers, including the Western Christianity in Europe, which rejected them, and did not recognize them in the Reformed or Eastern Orthodox Churches, which were considered to be biased in their beliefs. However, they can be said to have preserved the original Christian culture of the Middle East.

Thus the Assyrians are in fact an almost exclusively Christian minority group, originally from parts of modern-day Iraq, Syria, Iran and Turkey, and as a religious and ethnic minority group distinct from the Arab and Muslim majorities in the region, they face brutal persecution to this day. This incident adds a new dimension to the trauma of their long years of oppression, and this collective memory of trauma reinforces the close-knit identity of the community’s residents.

Bishop Mar Mari Emanuel, who was stabbed, also recently posted an audio message on social media saying that he is recovering quickly and has forgiven his attackers, and urging the congregation to remain calm and respect the law. In a recent meeting with religious leaders, NSW Governor Michael Cummins also called for calm and solidarity – compassion, understanding, cohesion, unity, and most importantly, peace, whether attending local churches and mosques, these people are there to be part of their communities, to find comfort and strength there. This is no place for violence.

It’s the cracks that allow the light to shine through

Unlike the belief held by many Australians that Australia is a Christian nation, this is not true.

Australia has been a secular state since the founding of the Commonwealth, and the 1901 Constitution prohibits the federal government from interfering with any freedom of religion. However, Christians have been the majority in the country since European immigrants settled here, with more than 90% of the population professing Christianity at the time, and only a small minority having no religious affiliation. While the number of non-religious Australians has increased over the past three decades, communities outside of the Christian religion have flourished in Australia, with Sikhism, Hinduism and Buddhism among the fastest-growing religions in the country, and these religions have flourished for their ability to provide connection, community and a sense of spirituality, particularly in serving new immigrant communities.

The 2021 Australian Population Survey showed that less than 50% of the population declared themselves to be Christians, and less than 20% of new immigrants are Christians. It can be said that newcomers do not have the same cultural identity as the original Australians as did immigrants during the Second World War. Therefore, it is a challenge for Australia to build a stronger sense of identity between new immigrants and the Australian nation.

Australia has always been committed to religious freedom, and extremism has no place. The Sydney church attack was an extremely disturbing incident, and for Australia to be a peace-loving nation, the community should be united, not divided. But is it really so easy to heal the rift between communities caused by the attack itself and the subsequent festering mass unrest?

In response to the growing threat of right-wing extremism in Australia, the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO) updated its definition of extremist groups in early 2021 – categorizing them as being driven by “ideology” or “religious belief”. The Sydney church attack was also categorized as a terrorist act because of its religious motivation. A new version of the Defense Strategic Review, launched last year, emphasized the need for Australia to move away from the old model of defense to a new approach of National Defence – a Whole-of-Government Approach or a Whole-of-Nation Approach. A Whole-of-Government Approach or a Whole-of-Nation Approach was adopted to cope with the competition of the big powers. In Australia, a secular and pluralistic country, a Whole-of-Nation Approach involves the unity of religious communities.

Australia is a multiracial country practicing multiculturalism, but recent international events and various localized wars have made people in Australia’s Middle Eastern communities particularly sensitive. In this climate, is Australia safer or more torn apart? How far can religious freedom go in this country? Perhaps continued secularization is the most viable path, freeing people from the establishment to truly see the individual, whether Christian, Islamic, Buddhist, etc., as a person who comes together in Australia with a shared vision of a happy life where there is no place for violence.

Reflections for the Chinese

The Chinese are often seen as irreligious, so many people think that the events in Sydney had little to do with them. However, ideologically speaking, the Chinese consider themselves to be “Chinese”, and today China (the People’s Republic of China) considers all Chinese in the world to be Chinese, a belief that dominates many Chinese.

Few Chinese from Southeast Asia identify themselves with their country of origin, and therefore most of them define their cultural roots as Chinese culture, and do not actively identify themselves with the Australian mainstream culture. Nowadays, the Chinese government is actively building up the relationship with the Chinese community in Australia, and more Chinese from China still consider themselves as Chinese, so it is easy to build up the idea that Chinese-Australians are also Chinese in each Chinese community. During the period of friendly relations between Australia and China, this idea was promoted and developed as a positive factor in promoting economic and cultural cooperation between the two countries.

However, in the past decade, China has become increasingly powerful and has challenged the legitimacy of the Western powers in dominating world politics. As a result, there has been a growing mistrust of and opposition to China in Australian society, and the community’s recognition of and trust in the Chinese has come under pressure. In recent years, Hong Kong people who came to Australia due to political pressure or persecution are even more dissatisfied with being regarded as “Chinese”, and some Hong Kong immigrants refuse to recognize themselves as Chinese. This has led to differences and divisions in the Chinese community, and I believe this is something that the Australian government needs to address.

The majority of Chinese Australians today are not refugees, but free immigrants who came to Australia by their own choice. They should be a group of people who recognize the values and culture of Australia, but it will take some time before they can fully integrate into the Australian society. As they come from societies with different governing cultures, they also show different responses to the values held by the Australian society. There are Hong Kong immigrants who embrace democracy and the rule of law as their core values, Taiwanese immigrants who do not consider themselves to be Chinese at all, and those who grew up with Chinese patriotic education (brainwashing?) and enjoy democratic rights and freedoms, but have not yet fully integrated into Australian society. There are also new immigrants from China who grew up (brainwashed?) with Chinese patriotic education and enjoy the rights of democracy and freedom while embracing the totalitarian rule of China. In fact, if these situations are not handled properly, the community conflicts caused by different religions and cultures in Sydney may also occur among the Chinese. I believe that this is something that the Australian government cannot afford to ignore.

Article/Editorial Department (Sameway Magazine)

Photo/Internet

You may like

Features

Chasing Speed, Chasing Risk: The Safety Myth Behind Modified E-Bike Policies

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 30, 2025

As Australia and the international community race to keep up with the green transition, a wide range of electric transport options—from electric cars to buses—have been rolled out. Among them, e-bikes have become the most widely adopted: accessible to all ages, spanning high-end to budget models, and used both publicly and privately. For many, they represent the ideal compromise between environmental responsibility and everyday convenience.

However, following a series of fires linked to modified e-bikes, the Victorian government announced that from 21 December 2025, any modified or non-compliant e-bike will be banned from trains and ticketed station areas. Factory-standard e-bikes may still be carried on trains, but they must not be charged, powered on, or ridden.

This raises a crucial question: is this new rule genuinely about protecting public safety, or is it merely a symbolic response designed to give the appearance of action?

Why Modify E-Bikes at All?

The original design philosophy behind e-bikes is fundamentally sound. They were intended as lightweight, environmentally friendly, and low-cost transport options. Compared with traditional bicycles, e-bikes require less physical effort and are particularly suitable for short urban commutes, climbing hills, or carrying loads. More importantly, they can serve as partial substitutes for cars, reducing carbon emissions and traffic congestion, while being especially accessible to the elderly, students, office workers, and people with limited mobility.

E-bikes are also meant to assist rather than fully replace pedalling, allowing riders to avoid exhaustion on long distances or steep terrain while still retaining the benefits of physical activity. In essence, their purpose is balance: safety, sustainability, and convenience working together.

Yet, as the saying goes, intentions do not always align with outcomes. Under distorted market incentives and real-world usage pressures, e-bikes have gradually drifted away from their original purpose. Modifications driven by user convenience—and impatience—have emerged as a natural consequence.

In pursuit of riding “faster and farther,” some users replace 250W motors with 500W units or install higher-capacity batteries, bypassing factory limits on power and range. Cost considerations also push those who cannot afford factory-built models to retrofit old or cheap bicycles with electric kits. Within DIY and tech-enthusiast communities, modifying e-bikes has even become a form of personal expression—an informal competition to outperform factory specifications.

But shortcuts always come at a price. The desire for speed, range, and aesthetic appeal inevitably brings increased safety risks.

The Risks of Modification—and Real-World Consequences

At its core, most e-bike modifications are carried out by hobbyists or individuals with limited technical expertise, making safety and quality highly inconsistent.

The most prominent risk lies in lithium batteries. While widely used, modified e-bikes often rely on uncertified batteries, unknown sources, or even second-hand cells. This frequently leads to mismatches between battery capacity, discharge rates, and motor demand, causing overheating. Modifications may also damage or bypass the battery’s BMS (Battery Management System), triggering thermal runaway and resulting in explosions or severe fires.

Structural limitations present another major hazard. E-bike frames and components were never designed for high power, high speed, or heavy battery loads. After modification, common issues include undersized wiring, poorly soldered connections, mismatched fuses, and incompatible chargers that introduce voltage or current errors. Frames, wheels, and braking systems originally built for human-powered cycling are suddenly forced to endure higher torque, greater speeds, and heavier loads—often without any upgrades. Modified bikes can exceed factory speed limits while retaining stock tyres, suspension, and brakes, revealing a dangerous pattern: riders overestimate their control skills while underestimating the physical limits of the vehicle.

These risks are not theoretical. On 2 September 2025, a serious house fire in Melton West was traced to a modified e-bike lithium battery that exploded while charging, reportedly upgraded to improve performance but at the cost of increased overheating risk. Earlier that year, in April and August, similar fires caused by modified e-bikes occurred at Blacktown and Liverpool train stations in New South Wales. These incidents were later cited by authorities as justification for banning modified e-bikes from trains.

A Case of Policy Misplaced Priorities

Does the introduction of new regulations mean the government is addressing the real problem? Not quite.

The government’s approach targets the most visible and easiest-to-police aspect: banning modified e-bikes from train systems, rather than confronting the underlying causes. While this may reduce fire exposure in public transport settings and allow officials to demonstrate swift action, fires do not occur because e-bikes enter trains. They occur in homes, garages, and on the street during charging.

The real danger lies not in modification itself, but in the long-standing absence of meaningful regulation over the aftermarket. High-power motors and battery kits can be easily purchased online with little to no mandatory safety testing or compliance labelling. Sellers face minimal accountability, while users bear the full risk.

Equally overlooked is the cultural shift surrounding e-bike usage. “Faster, farther, and easier” has become the primary goal for many young users seeking convenience without obtaining motorcycle licences. As a result, e-bikes are increasingly expected to perform like motorbikes, especially under pressures from urban commute times, delivery-platform economics, and social-media glorification of speed and modifications. Speed has evolved from a functional need into a status symbol. In such an environment, restricting usage locations or relying on post-incident penalties does little to reverse accumulating risk.

Lithium batteries—arguably the most critical link in the risk chain—remain poorly regulated at the import level. Without a unified certification system, users must judge compatibility on their own, and responsibility becomes impossible to trace once an accident occurs. Legal boundaries around DIY modification remain vague, reinforcing the perception that “it’s fine as long as no one catches you.” Enforcement becomes reactive, inconsistent, and scene-based rather than risk-based.

Cross-border online shopping further exacerbates the issue. Large volumes of low-cost, uncertified batteries and modification kits—often sourced from Chinese e-commerce platforms—enter Australia with inflated specifications and questionable quality. Many reuse reclaimed cells or mislabel capacity, yet evade strict inspection through small-batch or postal imports. Government oversight has lagged far behind market reality, allowing high-risk products to circulate freely. When regulation fails at the source, restricting user behaviour after accidents merely shifts responsibility onto the public.

By contrast, Canadian provinces take a fundamentally different approach. They focus on technical standards and market entry rather than usage location. Clear limits on motor power and assisted speed are enforced, while batteries and chargers must meet CSA or UL safety certifications. Vehicles exceeding these limits are reclassified as electric motorcycles, requiring registration, insurance, and compliance. Responsibility is clearly distributed among manufacturers, importers, and modifiers.

Canada addresses why fires occur. Australia focuses on where they occur.

Treating Both Symptoms and Causes

If the Australian government truly intends to reduce safety risks associated with modified e-bikes, banning them from trains is little more than a cosmetic fix. While it may reduce public exposure in the short term, it fails to address the underlying danger.

Effective policy must tackle the issue simultaneously at the source, regulatory, and educational levels.

A mandatory, unified safety certification system should be established for all e-bikes, batteries, and chargers, covering battery capacity, discharge rates, BMS integrity, and charger compatibility. Import and sales channels must be traceable, preventing high-risk products from entering the market. Modification rules must be clearly defined—what is legal, what is not—and accountability must extend to manufacturers, importers, sellers, and modifiers alike. Safe, certified upgrade pathways should exist so users are not forced into risky DIY solutions.

Education is equally critical. Through media, social platforms, public transport systems, and retail channels, users should be informed about the real dangers of battery overheating, short circuits, and structural limits, alongside their legal responsibilities. Promoting verified upgrade options and safety guidance can reduce accidents while fostering voluntary compliance.

Rather than suppressing the demand for speed, governments should regulate it. Certified upgrade standards could specify motor power, battery capacity, frame load limits, braking, and suspension requirements, allowing performance enhancements within safe boundaries. This would channel the existing “speed culture” into a controlled framework instead of letting it spiral into unregulated risk.

A longer-term solution would involve a modification registration and inspection system. Modified e-bikes that pass safety checks could receive official certification, enabling lawful use and clearer enforcement. This approach rewards compliance rather than punishing all users indiscriminately.

Finally, the issue of uncertified imported batteries must be addressed at the border. Mandatory testing, strict certification requirements, active market surveillance, and penalties for non-compliant importers and platforms are essential. A traceable responsibility chain would ensure that when accidents occur, accountability does not end with the user.

At present, Australia’s policy remains fundamentally misaligned—managing where incidents happen instead of why they happen. Without systemic reform spanning technical standards, market oversight, and user behaviour, risks will continue to migrate from trains to homes and other public spaces.

Only through comprehensive, source-based regulation can e-bikes fulfil their promise as safe, affordable, and sustainable urban transport—rather than remaining shadowed by preventable accidents.

After all, when we pursue environmental convenience while tolerating market loopholes and safety hazards, can such e-bikes truly be called transport tools that serve us?

Australia’s government has always taken pride in its multicultural society, even presenting it as a unique selling point for tourists and a beacon of hope for immigrants. Yet multiculturalism inevitably brings ideological differences, and ignoring these differences only sets the stage for tragedy.

The recent mass shooting at Bondi Beach (Hanukkah) in Sydney, which resulted in multiple deaths, prompted Australians to mourn the victims and condemn the attackers, which is a natural response. However, this tragedy also exposes a major blind spot of the Australian government: years of ignoring the steadily worsening anti-Semitism over the past two years directly contributed to this bloodshed.

Two Years of Ignored Warnings

From 2023 to 2025, anti-Semitism in Australia gradually increased, escalating from protests to arson attacks, all foreshadowing the mass shooting.

The earliest incident occurred on October 9, 2023, outside the Sydney Opera House. Approximately 500 people initially gathered at Town Hall, then marched near the Opera House, with police estimating around 1,000 attendees. The protest sparked public outrage because of the hateful slogans shouted, such as “F*** the Jews” and “Where are the Jews?” Yet, the police and government largely ignored it, underestimating the potential danger.

The hate crimes continued to escalate in 2024. On October 20, 2024, the Lewis’ Continental Kitchen in Bondi’s Curlewis Street was set on fire in the early morning hours, forcing the evacuation of residents above. This kosher family-owned restaurant had been operating for years and served the local Jewish community, who were deeply affected by the attack. In December of the same year, the Adass Israel synagogue in Melbourne was also targeted in an arson attack, causing serious damage and injuries. Although the police arrested the suspects and classified both cases as terrorist acts, the government continued to downplay their severity, with the Prime Minister merely offering verbal statements condemning racial hatred.

Subsequent anti-Jewish incidents in 2025 included two nurses in Bankstown using violent language toward Israeli patients and refusing care in February, as well as a white nationalist march in New South Wales in November, involving around 60 far-right members. The government’s response in each case was limited to verbal condemnation, brushing off the threats. Inevitably, the December Bondi Beach disaster occurred amid heightened anti-Jewish sentiment, resulting in 15 deaths and dozens injured, becoming the deadliest attack on Australia’s Jewish community in history.

The Root of the Tragedy

These successive hate-driven disasters were not random; they were a ticking time bomb fueled by specific factors.

A major cause is the oversimplification of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Certainly, Israel’s military actions in Palestinian territories, causing deaths and injuries, are excessive and worthy of criticism. But here’s the key distinction: Israel is a nation-state; its government is a political entity subject to critique. Jews are a transnational, cross-political community. The majority of Jews worldwide are not Israeli citizens, did not vote for Netanyahu, and hold diverse or even strongly oppositional views regarding Gaza.

Many people — including some politicians, academics, and social activists — reduce the world into a black-and-white dichotomy: “oppressed = absolute justice” and “powerful = original sin.” This logic leads to the dangerous equivalence: “Jews ≈ Israeli government ≈ oppressors.” In some universities and left-wing activist circles, anti-Semitism is repackaged as “anti-colonialism,” with Jewish students pressured to publicly denounce Israel to receive protection. Consequently, many non-Israeli Jews are treated as a monolithic political entity rather than a community, and their fears for personal safety — including the real risk of being attacked — are dismissed as “overreacting” or “distracting.”

Worse still, Albanese’s government, in pursuit of a superficial social harmony, chooses inaction out of political fear. To appease voters, including Muslim communities and progressive anti-war, anti-Israel constituencies, Albanese and his party sacrifice a smaller, high-risk Jewish population, offering only vague statements like “stay calm” or “both sides must respect each other.”

The fallacy lies in equating “Palestinians and Muslims have a right to be angry, so everyone deserves respect” with “these attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified by political reasons.” True freedom means no excuse can rationalize racial insults or attacks on others, regardless of cultural background. Yet government rhetoric has consistently stayed in the abstract: “I oppose all forms of hatred,” “we understand the pain and anger of communities,” or “we support peace, respect, and dialogue,” instead of clearly stating: “These attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified.” This leaves extremists free to exploit political arguments, while innocent people remain unprotected and harmed.

Ultimately, the tragedy was not caused by the government “supporting anti-Semitism,” but by political tolerance of latent hatred, systemic inertia, cultural blind spots, and the romanticization of Palestinian/Muslim anger, until the disaster exploded.

It is unfortunate that, to this day, the Prime Minister and the government have not assumed responsibility — simultaneously acknowledging Palestinian suffering while failing to enforce zero tolerance against violence and intimidation toward Jews. Politically, Albanese never directly dismantled the fallacy, instead allowing the misleading narrative: “Jews are being attacked because Israel did wrong.” This logic, if accepted, would absurdly suggest: “Russia’s invasion justifies attacks on Russian-Australians” or “China’s abuses justify threats against overseas Chinese.”

What Anti-Semitism Means

Some may think anti-Semitism only affects Jews, not other minorities. But this “mind your own business” notion is completely wrong — anti-Semitism is not just hostility toward one group; it is a society’s signal that hatred is being tolerated.

Once hatred is tolerated, it becomes a testing ground. Allowing attacks on Jews signals that people can be targeted because of their identity, faith, or heritage, stripped of basic dignity. The boundary is already broken.

The next target will never be only Jews. Today Jews may be labeled as “problematic,” “too sensitive,” or “asking for trouble”; tomorrow the same language could apply to Muslims; the day after, Asians, Africans, Indigenous people, or LGBTQ+ individuals. Hatred never needs a new reason — it just needs a precedent society permits.

As the saying goes, hatred is like a contagious disease. When exceptions are allowed, when people calculate “which minorities deserve sympathy and which can be sacrificed,” society is learning to ignore the humanity of others — a skill that will inevitably be applied to more innocent people.

Where Is Hope?

Given the despair and fear of the past two years of anti-Semitic attacks, is hope possible? Certainly. But it does not exist in political slogans or empty statements; it is embodied by those who refuse to normalize hatred.

The most immediate example is Ahmed Al-Ahmed, an Arab-Syrian Muslim who, during the Bondi Beach shooting, risked his life to stop the gunman and protect innocent Jews. Although he was shot multiple times and severely injured, he successfully disarmed the attacker and prevented more deaths. Global media praised his courage as a life-saving act. His actions shattered a persistent lie: this is not a “Jews vs. Muslims” issue, but a matter of human stance against violence and hatred.

After the Bondi Beach attack, many Sydneysiders and Melburnians held interfaith vigils and memorials. Jews, Muslims, Christians, and representatives from other communities joined, lighting candles and offering prayers. Leaders such as Bilal Rauf of the Australian National Imams Council publicly expressed mourning and support, embracing Jewish community leaders — a symbolic act of cross-cultural solidarity. Thousands more held similar ceremonies elsewhere, using silence, candles, and flowers to resist fear and hatred.

Interfaith support has appeared in other incidents as well. After the arson attack on a Melbourne synagogue last year, leaders from Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and Baha’i backgrounds came together to hold vigils and prayers, urging respect and compassion for all groups. Such collective actions reassure victims and send a strong message to society: hate will not be tolerated, and every act of solidarity is a concrete countermeasure against anti-Semitism.

Even acts less reported by mainstream media matter. Online videos showed a heavily injured pregnant woman, Jessica (Jess), shielding a 3-year-old Jewish girl with her own body, protecting her until rescuers arrived. The child’s parents later said she saved their daughter’s life, showing the importance of civilian intervention.

During the chaos, Bondi and North Bondi volunteer lifeguards rushed to aid victims before police or paramedics arrived, running through gunfire, using surfboards as stretchers, and escorting around 250 evacuees to safety. One pregnant woman even went into labor during the rescue, but volunteers ensured her safety. Their actions stabilized numerous victims and saved lives.

Looking at history, both Jews and Palestinians have endured prolonged persecution and injustice: Jews faced massacres, discrimination, and expulsion worldwide, while Palestinians suffered displacement, loss of homeland, and ongoing armed conflict. Although all sides in the Middle East conflict have made mistakes, the pain of both groups reminds us that when politics, power, and hatred dominate society, ordinary people become victims of violence and injustice.

Yet this shared suffering also offers an opportunity: if both sides can engage in dialogue based on mutual understanding and respect, without letting hatred cloud their judgment, it may be possible to overcome historical wounds and seek coexistence and reconciliation. It is in this space of rationality and empathy that society can truly learn to respect every group’s rights, without being controlled by anger and prejudice.

Ultimately, anti-Semitism is not a problem affecting only one group, but a test of society itself: who deserves protection? When the safety of any minority is relativized, everyone stands at greater risk. Yet it is precisely for this reason that empathy and courage are so crucial. Only when society draws clear and consistent boundaries — acknowledging the suffering of all groups and maintaining zero tolerance for hate and violence — does hope cease to be a slogan and become a reality that protects every individual.

Features

Examining Freedom of Speech in Hong Kong Through the Jimmy Lai Case

Published

4 weeks agoon

December 23, 2025

Jimmy Lai, the founder of Apple Daily, endured 156 days of trial under the National Security Law and was preliminarily convicted on December 15, 2025, on multiple charges, including collusion with foreign forces, publishing seditious material, and other conspiracy-related offenses.

The formal sentencing hearing will not take place until January 12, 2026, to determine the length of his imprisonment. Nevertheless, this verdict sends an undeniable signal and warning to Hong Kong residents: freedom of speech in Hong Kong is running out of time.

Freedom of Speech Is Not What It Used to Be

Since Hong Kong’s handover, the SAR government has retained much of the administrative culture and governance practices from the British colonial period. Before the enactment of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong was relatively broad. Media outlets could openly criticize officials, question policies, and publish investigative reports without immediate legal repercussions. Newspapers like Apple Daily thrived on sharp political commentary and incisive editorials; civil society and protest activities also operated within a certain degree of freedom.

Of course, freedom of speech was never absolute. Citizens still had to avoid baseless defamation or personal attacks. Overall, Hong Kong possessed a culture of debate, satire, and investigative reporting. Cartoonists could mock leaders, columnists could challenge policy decisions, and social media offered a relatively open platform for political discussion and engagement. Civil society could organize forums and large-scale peaceful marches, such as the 2003 anti-Article 23 protest that attracted 500,000 participants. The judiciary at the time was relatively independent, so criticizing officials or exposing corruption through the press did not automatically constitute a crime.

However, with the case of Jimmy Lai, the closure of Apple Daily in 2021, and the full implementation of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong has steadily declined. Media professionals, activists, and even ordinary citizens have begun to self-censor, and public discourse has visibly contracted. Hong Kong, once willing to expose wrongdoing, criticize the government, and conduct in-depth investigations, now bears little resemblance to its former self.

The Core Issues of Injustice in the Case

Under the forceful implementation of the National Security Law by the central government, the official narrative around Jimmy Lai has been uniform: “Lai sought foreign sanctions and cooperated with anti-China forces abroad,” “foreign powers glorified Lai’s actions in the name of human rights and freedom,” or “freedom of speech cannot override national security.” There is no room for debate. Nobody wants the police knocking on their door, so people naturally turn a blind eye.

But a closer analysis of the case reveals that these statements mask the deeper injustice of the crackdown on freedom of speech in Hong Kong.

First, the so-called “collusion with foreign forces” is extremely broad and vague. What exactly counts as collusion? Does speaking with foreign media qualify? The law does not clearly define the elements of “collusion,” the threshold of intent, or the degree of actual harm, allowing law enforcement and prosecution to rely heavily on after-the-fact interpretation. Ordinary public actions—such as giving interviews to foreign media, contacting overseas politicians or organizations, or calling international attention to Hong Kong’s situation—can now be reclassified as criminal acts. The core principle of the rule of law is predictability; citizens should clearly know what is legal and what is illegal. When legal boundaries are vague, people cannot adjust their behavior in advance to comply with the law, and lawful speech can be criminalized at any time, violating the fundamental judicial principle of nullum crimen sine lege (“no crime without law”).

Second, the case shows that under the National Security Law, the Chief Executive is allowed to freely select pro-Beijing judges and limit jury participation, clearly deviating from Hong Kong’s common law tradition. This blurs the line between the judiciary and the executive in politically sensitive cases. Even if a judge maintains professional integrity, the perception of independence is equally important. When politically sensitive cases are heard by executive-designated judges, defendants and the public naturally question whether the judiciary is free from political pressure. Once judicial credibility is undermined, rulings themselves are difficult to view as fully impartial, creating structural disadvantages for any defendant.

For instance, the judge stated during the trial that Lai “continued despite knowing the legal risks” and “intended to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party,” even declaring him the mastermind behind the entire conspiracy. The judgment described his use of the newspaper and personal influence as a coordinated propaganda campaign aimed at overthrowing the CCP. When the defense argued that Lai’s activities were within the scope of freedom of expression, the judge responded: “Opposing the government itself is not wrong, but if done in certain improper ways, it is wrong.” The judgment further characterized Lai’s actions as “a threat to Hong Kong and national security,” even claiming that he “sacrificed the interests of China and Hong Kong citizens.” Such politically charged language links speech directly to intent, raising doubts about judicial impartiality.

Additionally, the trial, spanning from 2023 to 2025, lasted 156 days—far beyond the original schedule. Prolonged legal procedures, combined with pre-trial detention or restrictions, caused ongoing psychological, physical, and financial pressure on Lai, particularly severe given his advanced age. His daughter, Claire Lai, stated in multiple media interviews that his health continued to deteriorate in prison, with significant weight loss and physical weakness. His son, Sebastian Lai, publicly appealed to international leaders to monitor his father’s health, fearing he might not have much time left. The prolonged trial itself constitutes an informal punishment, yet the authorities ignore the defendant’s health while asserting that the case is “lawful” and “protecting national security,” framing external criticism as foreign interference. Under this context, dissent is no longer considered part of public discourse but a potential threat, and the defendant’s human rights are irrelevant. Even before sentencing, Lai has suffered tremendous mental and physical trauma, while the prosecution, as an instrument of the state, bears no comparable burden. This asymmetry places the defense at a disadvantage and undermines the practical significance of the presumption of innocence.

Human Rights Betrayed by China

If the central government can crush a media figure simply for expressing opinions, citizens—especially the younger generation—might wish to fight back. But fantasy aside, reality must be acknowledged: Hong Kong will not allow any so-called “rebellion” to occur.

First, with the Sino-British Joint Declaration effectively undermined, the central government is no longer bound to follow the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Analysts have reasonably pointed out that the National Security Law bypasses Hong Kong’s normal legal processes, showing that the city’s once-vaunted rule of law is eroding. Once developments are circumvented in this way, the central government deems it necessary to monitor speech through ad hoc legal measures. From the arrest of activists like Miles Kwan to the prolonged trial of Jimmy Lai, dissatisfaction with policies—whether large or small—is no longer tolerated.

The ICCPR’s Article 19 protects freedom of expression, including political commentary, criticism of the government, press, publications, and international exchanges. Independent media, investigative reporting, and critical journalism are foundational to civil society’s freedom of speech. Article 14 guarantees fair trial rights, encompassing independent and impartial courts, fair bail procedures, public hearings, and the right to full defense. Yet the central government has violated both of these basic provisions. Under the National Security Law, the legal definitions of “seditious acts” and “collusion with foreign forces” are extremely vague, turning normal journalistic and public speech—comments, interviews, and international engagement—into potential criminal acts, producing a severe chilling effect. Such vagueness in law itself constitutes an infringement on freedom of expression.

Similarly, fair trial rights are compromised: judges in national security cases are designated by the Chief Executive, bail thresholds are exceptionally high, trials may occur without a jury, and Beijing retains ultimate interpretation authority. UN human rights experts widely regard political cases subject to executive influence as violating fundamental fair trial standards under international law.

Articles 21 and 22, which protect freedom of assembly and association—including peaceful protests, political organizations, and normal operation of civil groups—have also seen clear regression in Hong Kong. Numerous civil organizations have disbanded, and protests are treated as potential national security risks, with participants possibly facing retrospective criminal liability—a disproportionate and preventive restriction.

UN human rights experts, special rapporteurs, and treaty monitoring committees have repeatedly pointed out that the National Security Law’s broad definitions and implementation methods do not meet the necessity and proportionality standards required under international human rights law. The core issue is not whether the state has the right to maintain security, but whether national security is being used to completely override human rights. Rights are not gifts from the government; they are protections that cannot be arbitrarily revoked. When “national security” becomes an infinitely expandable and unquestionable rationale, rights once guaranteed under the ICCPR cease to exist legally and become political privileges revocable at any time.

How the Central Government Circumvents the ICCPR

China’s ability to bypass the ICCPR is not accidental; it stems from its historical, selective participation in the UN human rights framework. China signed the ICCPR in 1998 but has never ratified it, meaning it has never formally recognized its legal binding force domestically. Under international law, unratified treaties do not create full legal obligations for the state. Moreover, China’s “dualist” legal system requires that international treaties be transformed into domestic law to be enforceable in courts; without this, they cannot be invoked or applied in judicial proceedings.

This design allows China to diplomatically acknowledge human rights values and participate in UN discussions while retaining complete interpretive and enforcement sovereignty domestically. Even though Article 39 of the Basic Law states that the ICCPR continues to apply in Hong Kong, its practical effect is constrained by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s ultimate interpretive authority and the constitutional priority of national security. Within this structure, the common law culture and human rights protections inherited from Britain are not outright rejected but are institutionally neutralized. When the central government deems certain rights in conflict with national security, international covenants and local constitutional commitments can be reinterpreted, suspended, or effectively set aside, without immediate international legal consequences.

This institutional reality explains why Jimmy Lai gradually lost legal protection. British-established common law in Hong Kong was founded on limiting power, prioritizing individual rights over the state, and judicial checks on the executive. Article 39 of the Basic Law was intended to lock in this system and the ICCPR so that post-handover Hong Kong residents would retain fundamental freedoms. However, China’s consistent refusal to ratify the ICCPR and insistence that international human rights treaties cannot override national sovereignty allows it, through NPC interpretations and the National Security Law, to nullify the covenant’s substantive force.

Jimmy Lai’s case is a concrete manifestation of this systemic shift. Activities that would have been protected—journalistic work, political commentary, international engagement—are no longer treated as protected civil rights but are redefined as security risks subject to state intervention. With Britain’s rights-centered legal culture powerless to check central authority, and the ICCPR legally unenforceable in China, Lai and all Hong Kong citizens have effectively lost the last line of institutional protection. China does not simply “violate” international human rights law; it uses institutional design and hierarchical restructuring of power to transform Hong Kong citizens’ freedoms and legal protections from inalienable rights into political privileges revocable at will.

Crucially, many Hong Kong citizens fail to recognize that the National Security Law’s revocation of freedom of speech is legally possible precisely because China has never formally recognized the ICCPR. Signing in 1998 without ratification, the ICCPR has never been incorporated into Chinese law, meaning it cannot be directly enforced in courts. Many mistakenly believe that Article 39 of the Basic Law guarantees irrevocable protection, ignoring that its practical effect is constrained by NPC interpretations and the constitutional prioritization of national security. Thus, the National Security Law, deemed to safeguard the country’s fundamental interests, reclassifies freedom of expression not as a right protected by international law but as an exception fully limited for security reasons. This is the harsh reality that citizens still hoping for “protection under international law” have yet to fully grasp.

Lessons from the Jimmy Lai Case

Jimmy Lai’s case transcends individual criminal liability or a single judicial ruling; it symbolizes a systemic transformation in Hong Kong. In a city that was once legally bound by the ICCPR, a media founder has been convicted for his journalistic stance, political commentary, and international engagement. This demonstrates that the National Security Law has effectively reshaped the boundaries of speech and the judiciary. The case reflects not merely a ruling against one defendant but a governance logic that redefines normal civic behavior as a national security risk. Under this logic, press freedom, fair trials, and civil society are no longer institutional cornerstones but variables that can be sacrificed. Lai’s trial marks a clear transition from rights protection to political permission.

In this harsh reality, leaving Hong Kong is not shirking responsibility; it is a rational choice for risk management. When institutional resistance has been criminalized, preserving personal freedom, dignity, and future prospects is often more practical than futile confrontation.

For those choosing to stay in Hong Kong, the priority is not nostalgia or sentiment but a clear-eyed recognition that Hong Kong no longer operates under the system promised by the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The city is fully integrated into China’s political and security governance framework. Within this structure, international support, foreign government statements, or UN mechanisms can offer only limited symbolic effect. This is not “foreign betrayal” but a reflection of international political realities. Residents staying must understand the choice they are making and bear the risks and restrictions of a contracting legal and civil environment.

For those considering emigration, illusions must be discarded. Certain institutional protections and freedoms once present in Hong Kong have effectively vanished and will not return simply because of personal desire. Those who ultimately stay must accept living in a society where speech, organization, and political participation are tightly constrained. For undecided individuals, the Jimmy Lai case is an unavoidable benchmark for careful consideration. It clearly defines the boundaries of systemic risk, and making the decision to leave at this stage is not yet too late.

For Hongkongers already abroad, the next challenge is not only to mourn what Hong Kong has lost but to rebuild life, identity, and future on new soil. Only then can leaving be more than retreat, instead becoming genuine rebirth and forward movement.

Listen Now

Scam Kingpin Chen Zhi Arrested in Cambodia and Extradited to China

Severe Wildfires Spread Across Southeastern Australia, Victoria Declares Disaster

Iran Government Nationwide Internet Shutdown, Starlink Blocked

Trump’s Arrest of Maduro Sparks Congressional Opposition

Chasing Speed, Chasing Risk: The Safety Myth Behind Modified E-Bike Policies

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

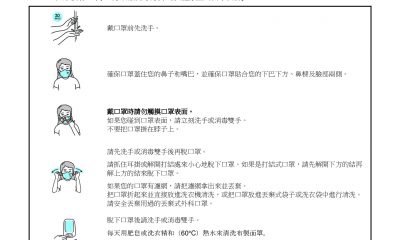

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單