Features

I’m an Indigenous Chinese Australian!

Published

1 year agoon

I’m an Indigenous Chinese Australian! (Part 1)

This year marks my 30th year living in Australia. Through writing, volunteering, and social dancing, I’ve made countless friends from all walks of life: Australians, Europeans, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Filipinos, Malaysians, North Americans, Indians, New Zealanders, and even South Africans. I’ve had great teachers, good friends, bad influences too, all from across the globe. Life has been vibrant, interesting, and long. However, I regret that not one of my friends is an Indigenous Australian, and I know very little about Indigenous communities, their culture, and traditions. This regret often leaves me feeling empty, as though something is missing. Over the years, I’ve only met two Indigenous women: one was a friend’s girlfriend whose grandmother was Indigenous, but she was fair-skinned with delicate features, and there was no outward sign of her Indigenous heritage. The second was Professor Marcia Langton AO, a professor at the University of Melbourne. I first saw her in 2008 when I interviewed the famous Australian painter Zhou Xiaoping (see my article “In Search of Dreams in the Indigenous Dreaming World” in Issue 85 of Sameway). I met her again at a Lunar New Year banquet at Zhou’s house the same year. In 2012, at the screening of a film about Zhou Xiaoping (see my article “Ink and Ochre” in Issue 314 of Sameway), I met Professor Langton again, but both times, I missed the chance to speak with her. In recent years, this sense of loss and regret has grown stronger, eventually prompting me to begin a quest to learn more about the First Nations of Australia.

Indigenous Australians, a term that refers collectively to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, are the descendants of the original inhabitants of Australia before European colonization. The term “Indigenous Australians” is a broad one, encompassing many different groups with significant distinctions between them. They may not share close connections or common origins, with each community having its own unique culture, customs, and language. It’s estimated that when Europeans first arrived, there were around 250 Indigenous languages. Now, only about 120 to 145 languages remain, most of which are endangered, with only 13 considered secure. Most modern Indigenous Australians speak English that is influenced by Indigenous vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammatical structures, a form known as Aboriginal English. Estimates of the population at the time of European settlement vary, with some suggesting between 318,000 and 1,000,000 people. They mainly lived in the southeast, which mirrors today’s population distribution. The current Indigenous population is 798,365, with 73% identifying as Christians, 24% having no religion, and 1% adhering to traditional Indigenous beliefs. There is no academic consensus on the relationship between the first inhabitants of the Australian continent and modern Indigenous Australians. However, most scholars agree that the earliest human remains found in Australia date back between 64,000 and 75,000 years, making them descendants of the earliest groups to leave Africa for Asia. Since 1995, the Aboriginal flag—red and black with a yellow sun—and the Torres Strait Islander flag—blue and green with a headdress symbol—have been recognized as official national flags in Australia. (Note 1)

Last week, through a friend’s introduction, I had the opportunity to learn more about Indigenous culture via several Australian television programs. The stories I’ll share here are based on ABC broadcasts (May 2020).

The Aboriginal Chinese Doll

I’m Brenda, an Elder of the Bidjara-Wakka Wakka nations. At 68 years old, I’ve always been curious about Chinese culture. Why? Because my grandmother used to call me “Chinese Doll.” I found the answer when I was four years old. It was the first time I discovered that I had Chinese ancestry. One day, while playing with other kids, I asked my grandmother, “Why do you call me Chinese Doll?” She told us that we were descendants of Chinese people. We continued asking, and she explained that my great-great-grandfather was Chinese. I grew up in Gayndah, a small town about 350 kilometres north of Brisbane, where my mother’s family are the traditional custodians of Wakka Wakka Country. Apart from that conversation with my grandmother, Lucky Law, and the taste of the fried noodles my mother May used to make, I knew very little about my Chinese roots, and even less about my mysterious Chinese great-great-grandfather. I couldn’t learn much from Lucky, as marriages like hers were seldom discussed back then. I only asked that day out of curiosity, but that curiosity has stayed with me, leaving a big gap in my life.

The First Generation of Chinese Shepherds

I’ve worked as a part-time teacher at a public school in Queensland for nearly a decade. A few years ago, I started exploring my family history in my spare time. My family tree reveals that one branch can be traced back to my great-great-grandfather John Law. He arrived in Australia around 1842 as a shepherd from Xiamen. He worked in the Gayndah region, where he apparently met my great-great-grandmother, and they married. It turns out I’m about one-fourteenth Chinese. In the 1840s, around 3,000 Chinese labourers, mainly men and boys, were transported from Xiamen to Australia to work as shepherds, spreading across modern-day Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland. Dr. Maxine Darnell has been tracing the history of these shepherds, who were brought under five-year contracts and worked under harsh conditions as part of the first organized wave of Chinese labour to Australia. They helped meet the labour shortage after convict transportation to Australia ceased in the 1840s, before the influx of Chinese gold seekers in the 1850s and 1860s. As contract labourers, they were bound to their employers, unable to freely leave for the goldfields like many free workers. While little is known about the reasons behind their migration, it coincided with China’s recovery from the Opium War, when the lure of a better life must have been appealing. The story of labourers seeking a better life is a timeless one.

From Hostility to Intermarriage

The interaction between Chinese and Indigenous Australians dates back at least 150 years, though much of this history remains undocumented. Dr. Sandi Robb has been researching the relationships and marriage patterns between Chinese men and Indigenous women in Queensland. According to Dr. Robb, the early relationship between the two communities was fraught with “hostility and fear.” From the Indigenous perspective, the Chinese were unfamiliar people, different in appearance and dress, trespassing on their land without permission, thereby violating Indigenous law. However, over time, Indigenous marriage customs began to break down, and instances of intermarriage with other ethnic groups appeared. By 1890, Indigenous women were often left with no choice but to marry outside their communities due to the loss of traditional marriage partners, often due to violence. Both the Indigenous and Chinese were marginalized and looked down upon by white settlers. John Law was one of the few Chinese shepherds who married an Indigenous woman. Their daughter, Kate Law, married Chinese shepherd James Coy in 1877, and they had 11 children, including my grandmother, Lucky Law.

Indigenous people and Chinese workers formed friendships and connections that bridged their worlds. Both groups faced discrimination, and like today, that prejudice still affects both Indigenous Australians and Chinese. I believe that both groups learned much from each other, including cultural practices and agricultural knowledge related to land and cattle. In Gayndah, there were also orchards and citrus groves. In 2019, the Queensland government recognized the contributions of Chinese shepherds in irrigation and crop production in the Darling Downs region.

The Quest for Chinese Roots

My journey to trace my family history would have been much more difficult without the help of a Chinese friend. In 2018, I met a young Chinese man named Xianyang Tang on Facebook, and we quickly became friends. Over the past two years, with his help, I’ve uncovered many unknown aspects of my family history. Xianyang knew how deeply I wanted to find at least one relative and learn more about my great-great-grandfather’s origins, so he helped connect me with the Luo clan in Xiamen and local Chinese people. However, the search hit a roadblock when we couldn’t confirm which branch of the Luo family my ancestor belonged to, possibly due to the destruction of Luo family records during the Cultural Revolution. Xianyang was moved by my determination to uncover my roots and volunteered to help me. He visited me during my illness and even bought shoes and hats for my children. To me, he’s like family. He believes that my ancestors came from the Luo clan in Xiamen, but the search continues.

I’ve always felt proud of my identity. I have a large family descended from John Law, and none of us has ever denied our Chinese heritage. My dream is to visit China, especially Xiamen, to see it for myself and imagine the footsteps of my great-great-grandfather. While I know a lot about Indigenous culture, I’m part of two cultures, and I’ve decided to explore that other half.

Since the 19th century, Chinese and Indigenous Australians have walked side by side with untold stories!

Hi, I am a Chinese Aborigine in Australia! (II)

Recently, I had the pleasure of meeting CityMag and Ngarrindjeri (multidisciplinary) artist Damien Shen on the program to talk about his upbringing and what it means to be Aboriginal and Chinese.

Yellah Fellah: The Yellow-Skinned Family Man

Yellah Fellah is a colloquialism, an Australian term for yellow people. I, Damien Shen, am what Australians call Yellah Fellah, the yellow-skinned guy. However, my Aboriginal and Chinese backgrounds are deeply connected, and my Chinese heritage played an important role in my childhood. I am not sure where I would be today without the benefit of my Chinese heritage. My father was born in Hong Kong but was sent to boarding school in Adelaide. My grandparents thought the Communists would soon take over Hong Kong, so my father’s sister was sent elsewhere and then he was sent to Australia. I was born in Adelaide and my grandparents, who lived next door, were important people in my childhood. I think as I got older I appreciated more the Chinese side of things, that they were able to build up such structures, things that happened in my father’s life and so on. My Chinese grandmother felt it was her duty to keep order in the home – breakfast would be brought out at a certain time and dinner was always at 6pm. Grandparents provide a safe structure for children to live in. Although proud of my Chinese heritage, I admit that growing up in Australia with undeniable racism against Asians was challenging. I don’t speak Chinese because when my father came here, there was a lot of racism, so he was like, “No, you’re speaking English.” He wouldn’t encourage us to speak Chinese. At home he spoke Cantonese, and my grandparents spoke Cantonese, Mandarin and Shanghainese, and then they would go around the table and speak English to us. I recall my first job at a Chinese restaurant, where it was harder to fit in because I didn’t know the Chinese language. I was perceived as someone with long hair who didn’t speak Chinese, which was almost a bit of a novelty to the Chinese. I was there, but never really connected with the Chinese.

My mother’s Ngarrindjeri ethnicity, my Aboriginal heritage, was also crucial to my childhood. Growing up, I always knew I was part of an Aboriginal community and had many Aboriginal cousins with whom I spent a lot of time. One of those family members was Uncle Moogy. Moogy, who everybody knows – he’s my mom’s brother, so he’s actually my real uncle, and I grew up with him. There were always a lot of children in his house and we always spent the night there, so it was always very fun and memorable and I’m still very close to him. Although I now appreciate my Aboriginal and Chinese heritage, there are still struggles, especially at a young age. When I was in about 10th grade, I encountered a lot of racism in terms of being Asian or Aboriginal – basically, “they” had two ways of dealing with me. Then I changed schools and things changed immediately because I went to a very multicultural school. Suddenly, I didn’t have that pressure to ‘stand out’. It wasn’t until I was older that I started researching my Aboriginal heritage. As you get older, you start to think more about genealogy, history and things like that. …… It’s so fascinating when you look at what it means to be an Aboriginal person with family ties from a genealogical perspective. Anyone you meet, you call each other by name, but you’re not quite sure how far apart we are – are we really cousins? Then, on the other hand, you see what being Aboriginal means politically, historically, what happened to the Ngarrindjeri people, so part of my work deals with that. I looked back at my own life in two different contexts and felt blessed. I was lucky to be able to experience it through two lenses: dual identity, or dual background – it’s an interesting thing. As I’ve experienced, you don’t always fit into the Aboriginal community environment, especially when I was young, I felt that. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten to know more Asian Aboriginal people, and we all look the same.

Yellah Fellah for OzAsia explores storytelling through an Indigenous Asian lens.

Yellah Fellah for OzAsia, an art exhibition curated by Catherine Croll, is on display at the Adelaide Festival Centre in 2023. This fascinating and inspiring exhibition featured the work of four different artists with Asian and Aboriginal traditions. I am exhibiting my own work alongside Gary Lee, Caroline Oakley and Jason Wing to show our personal interpretations of our backgrounds through the art form, which is essentially a gathering of many artists with Asian and Aboriginal traditions. For me, it’s Chinese and Aboriginal, and I think the artists will be proud of this mix of hybrids. I don’t speak for any other artist. …… Having a Chinese and Aboriginal heritage is something I’ve always been extremely proud of. You don’t see as much Aboriginal Chinese in South Australia as you do in the north of Darwin, there’s more of a mix of Asian Aboriginal cultures, but I’ve felt it’s quite unique here for a while now, so that’s cool. Curator Catherine says Asian-Australian relations began centuries before the European colonization of Australia, when Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory began to build a sea cucumber trading network with Malaysia and then on to China. I created a pewter skull fragment at an anatomy lab in Virginia entitled Life Behind the Pen, which is a history of the theft of human remains – many of the Ngarrindjeri people’s remains were stolen and shipped overseas. Uncle Moogy had a huge influence on a large group of Aboriginal leaders who travelled abroad to find these remains and repatriate them to Australia. My work here embodies that idea, and the photographs that Uncle Moogy and I have deliberately taken in this ethnographic way are like a real classic style of documenting things at a certain point in time, kind of like a drama of that history. The artwork called “Portraits” was a personal favorite of City Magazine, black and white portraits of my grandparents, sisters and uncles. Then I was inspired to organize a painting workshop with an American, and I thought, I don’t mind documenting all the stories around my mom. And then on the other hand, I’m going to document my Chinese grandparents and my sister as part of this series, linking the Chinese and Australian Aboriginal elements.

Chinese Aboriginal Women Writers

Not long ago, I saw some exciting news on SBS Chinese TV: Ms. Alexis Wright, a Chinese Aboriginal woman, won $60,000 and the Stella Prize for non-binary writers this year for her novel Praiseworthy, which beat out 227 entries. 2018 is the year that she writes about Aboriginal chiefs. In 2018, her collective memoir of Aboriginal chiefs, Tracker, also won the Stella Prize, making her the first author to win the award twice. She also won the Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s highest literary prize, for Carpentaria. Described by the New York Times as “the most ambitious and accomplished Australian novel of the century”, the 700-page book has been described as a great book in many ways, telling the story of the John Howard. Howard government’s 2007 military intervention in a Northern Territory community, the story of a small town whose inhabitants have been struck by a haze, and the story of the Aboriginal people who have been forced to live with the government’s military intervention in their community. This is a story of Aboriginal ancestry and ecological disaster. The characters’ reactions to the situation are allegorical, ranging from the comic to the tragic: one man devises a plan to replace Qantas with five million donkeys across Australia, another dreams of being white and powerful, and a third, apparently named Aboriginal Sovereignty, becomes suicidal. The judges were unanimous in stating that readers would be inspired by the aesthetic and technical qualities of Worthy of Praise and struck by Wright’s staccato rhythms of satirical politics, and that the award was rightfully given to Wright.

Challenge Yourself

Wright made a commitment long ago to challenge herself in whatever she writes, and her ambition has grown over the years. She began writing this novel about ten years ago, much of it during her tenure as Boisbouvier Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Melbourne. The process required Wright to pause and restart many times as she tried to evoke the slow pulse of central and northern Australia, to capture the scale of the period and the immense difficulties of the time, to challenge the reader’s indifference and to try to replace it with a deeper understanding. In an interview with the Australian Associated Press AAP, Wright pointed out that there is no harm in exercising the brain through the reading of good books. People are happy to go to the gym for a good physical workout, and there is no harm in a good workout for the mind.

Chinese Great-Grandfather & Native Great-Grandmother

“I come from one of the greatest storytelling worlds,” Wright said at the Stella Prize ceremony, “We are a culture of storytelling. Some of the most important, richest and longest-running epical law stories belong to the indigenous cultures of this land.” Wright, 73, is of Chinese descent. His great-grandfather came from Kaiping, Guangdong Province, to make a living in the Gulf of Carpentaria, a remote region in northern Australia, following the gold rush of the 19th century, and later married his Waanyi Aboriginal great-grandmother. Wright was invited to Shanghai for Australian Writers’ Week in 2018 and revealed in a media interview, “My great-grandfather was Chinese, but I don’t know him or the exact location of his hometown. I think it was somewhere in Kaiping, Guangdong. In the 19th century in Kaiping, a lot of Chinese people left their hometowns and went to the United States, Canada and other places to look for gold. Great-grandfather brought a lot of knowledge about China to the Gulf of Carpentaria, and he taught community members about irrigation and farming and growing vegetables.” She made a trip to Guangdong in 2017 to search for her roots, but unfortunately was unable to find any trace of her great-grandfather, after all, it was too long ago. Her books are available in Chinese translation, including the Franklin Award-winning Carpentaria and the full-length novel The Swan Book.

Bridging the Gaps in Australian History

During an unusual trip to the Northern Territory in 1988, renowned Australian painter Zhou Xiaoping was rescued by three Aboriginal teenagers when he was lost on a vast sandbar, which initiated his intense interest in Aboriginal culture and profoundly influenced his subsequent works, making Aboriginal people the only protagonists of his paintings. Through understanding, respect, and sincerity, he broke the barrier and formed decades of friendship with the Aborigines, making friends with Jimmy Chi, a Chinese Aboriginal musician, and Peter Yu, a professor. (See my articles “Seeking Dreams in the Aboriginal Dream World”, “Ink and Ochre”, and “Exploring Aboriginal History of Chinese Descent” in the 85th, 314th, and 665th issues of The Wayfarer) In 2022 Mr. Zhou initiated a project, Exploring Forgotten History, which is a project to explore the history of Aborigines in China, and to explore the history of the Chinese Aborigines in the world of Aborigines in the world of Chinese culture and culture. In 2022, Mr. Zhou initiated a project entitled “Exploring Forgotten Histories” to study Aboriginal people of Chinese ancestry, the significance of which is to fill in the gaps in Australian history. In the study of Chinese history, there is a large amount of information on the Chinese gold rush, but the relationship between the Chinese and the Aboriginal people is seldom covered. Why is it that in the early gold rushes in Bendigo and Ballarat, Victoria, there were not many intermarriages between the Chinese and Aboriginal people, and why are there not many Aboriginal descendants left behind? This is an important part of our history that we are gradually forgetting. Mr. Zhou’s research and the emergence of Aunty Brenda Kanofski, Damien Shen, Alexis Wright, Jimmy Chi, Peter Yu and other Aboriginal people of Chinese ancestry are like a jigsaw puzzle, putting together a picture of the past that has rarely been talked about or forgotten, showing the rich and complex interactions between the descendants of two of the oldest civilizations in the world, the Bendigo and the Ballarat. It shows the rich and complex interactions between the descendants of two of the world’s oldest civilizations. Will all this contribute to the integration of Australia’s diverse peoples and the harmony of its cultures? We look forward to it!

Knowing, Understanding and Respecting Aboriginal Culture

As we enter the month of May, the message of “Reconciliation” has appeared frequently in the media. What is reconciliation? Why Reconciliation? How to reconcile?

According to the Oxford Dictionary, “Reconciliation” means to end a disagreement or conflict with someone and start a good relationship again. But in Australia the concept of reconciliation is not so simple. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians have always tried to reconcile their differences, and Reconciliation is of great importance and significance to the nation. National Sorry Day is celebrated on 26 May each year, followed by National Reconciliation Week from 27 May to 3 June. The start and end dates of the week are historically significant, and are designed to promote the reconciliation of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The week begins and ends with historically significant dates to promote reconciliation between Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal Australians. This year, the theme for National Reconciliation Week 2024 is ‘Now More Than Ever’, and now more than ever, we have the opportunity to think about how we can use this knowledge and these connections to create a better Australia. Let’s learn and reflect on our shared history, culture and achievements with the Aboriginal community through the presentations of SBS Chinese Aboriginal reporter Mr. Ryan Liddle and CEO of Reconciliation Australia (National Reconciliation Association Chief Executive Officer) Aboriginal Ms. Karen Mundine.

History of Reconciliation Week

Reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians can be traced back to the arrival of the Englishman James Cook in 1770; it is also thought to have begun with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and was formalized with the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Finding that too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were incarcerated and often detained, the commission submitted a report with more than 300 recommendations to address the crisis. While many of the recommendations have yet to be adopted, the last recommendation in the report, No. 339, stands out: initiate a formal reconciliation process. The Aboriginal Reconciliation Commission Bill was passed by Parliament with the support of both the government and opposition parties, and in 2001 the Commission was replaced by a new organization, Reconciliation Australia, which is still in operation today. Before the handover, two key events marked new beginnings, signalling a promising new era. Karen Mundine said: “We’ve seen governors, territory leaders, federal governors and prime ministers from all states come together to make a commitment to the spirit of reconciliation, and what we really need to do is to build positive relationships, to make sure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are seen as Australians, the first Australians, and that we are the oldest continuous culture in the world, and that we celebrate this uniqueness and we are proud of it. We celebrate this uniqueness and are proud of it. Ryan Liddle said: “On this day, this week, Reconciliation Australia was born, this was our starting point, nearly a quarter of a million Australians marched on the Sydney Harbour Bridge in support of reconciliation on a freezing cold and windy morning, and it was a truly transformative moment, a moment of unprecedented support from a wide range of communities to usher in a millennium of new opportunities to join together in a common journey to improve race relations. Since then we have had many successes, launching thousands of Reconciliation Action Plans, raising awareness of Aboriginal issues amongst the general public and generally improving the overall image and status of Aboriginal people in Australia.”

The most significant moment was the government’s action on February 13, 2008, when then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said in Parliament, “We apologize for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have caused deep grief, pain and loss to our fellow Australians. Prime Minister Rudd apologized to the nation, and as the world watched, there were cries of relief, tears of joy and sadness, and many Australians took to the streets holding up signs that read: I’m Proud to say Sorry! This day is known as National Sorry Day in Australian history. The next big push for reconciliation came about a decade later, in late May 2017, when a citizen-led Aboriginal National Constitutional Conference, including Aboriginal leaders, academics, social activists and others from across the country, worked hard to reach a rare consensus to constitutionally authorize the creation of an Aboriginal voice in Parliament, a treaty, and the establishment of a Truth Commission. For Aboriginal people, this sovereignty is a spiritual concept that has never been ceded or extinguished, and exists alongside the authority of all levels of government.20 In October 2023, a referendum to affirm the Aboriginal and Tortugas Channel Islander National Congress failed, and Australians voted down the establishment of an Aboriginal and Tortugas Channel Islander National Congressional Voice.

Respect for Aboriginal Etiquette

Why is it important to show respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ceremonies? Because an understanding of these ceremonies can affect our behaviour and our relationships with Aboriginal people. Exploring the richness of Aboriginal traditions, getting Aboriginal etiquette right and learning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customs are fundamental to respecting Australia’s heritage and the land we all live on. Mr. Thomas Mayo, advocate and writer for the Kaurareg, Kalkalgal & Erubamle peoples, introduced the five steps to get Aboriginal etiquette right, to reconcile and to become one.

Ⅰ. Introduce yourself appropriately

Julie Nimmo says, “When I introduce myself to other Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, it is important to say what people and family I belong to. When we talk about family, we talk about our ancestors from the past, but when we meet people from another country, we often introduce ourselves as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander or Aboriginal Australians”. Thomas Mayo said, “I would introduce myself as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander because of family ties. Torres Strait Islanders are more closely related to Pacific Melanesians, and Aboriginal Australians are from the Australian continent, and we have different cultures and languages.

- Never abbreviate

Properly refer to Aboriginal people by referring to Australia’s first inhabitants through terms such as ‘Aboriginal’, ‘native’, ‘Torres Strait Islander’ and ‘land’, with the first letter of each title capitalized as a sign of respect. Never abbreviate the terms Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander and avoid using acronyms or other pejorative terms that were used in colonial times, as this can really offend Aboriginal people. Do not use acronyms such as “ATSI”, which is an abbreviation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and has historically been used as a pejorative insult to Aboriginal Australians, who are very particular about what they call themselves and can be deeply hurt by hearing offensive terminology.

III. Welcome Ceremony

Before the event begins, people participate in a traditional Welcome to Country ceremony or an Acknowledgement of Country ceremony. The two ceremonies are different. The former is a very important sacred ceremony, conducted by an Elder of the place where you are, welcoming the participants to commemorate the past, and may take the form of speeches, dances, or fireworks. The latter ceremony, which can be conducted by anyone, is an important welcome offered at important meetings. No matter where we come from, we still belong to the land, and recognizing and thanking our guardians and elders shows that we know and respect the land. In the old traditions, an Elder was a respected member of the community who had reached a certain age and had the cultural and intellectual wisdom to teach the people moral behaviour. Elders were usually referred to as “Aunty” and “Uncle” (aunt and uncle) as a sign of respect, and non-indigenous people had to first seek permission to use these titles.

- Don’t judge a person by his or her appearance

Never question or assume a person’s Aboriginal identity based on physical appearance. Many Aboriginal people are survivors of the Stolen Generation. Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their homes between the 1910s and 1970s. Thomas Mayo said, “It is offensive to ask Aboriginal people about the percentage of their Aboriginal ancestry because the colonizers were trying to assimilate us in this country by reproducing us so that we eventually disappeared. 2008 Prime Minister Rudd apologized to the nation: ”On behalf of my government, I am sorry! On behalf of my government, I am sorry! People were criticized for the colour of their skin, this was called the assimilation policy, where a percentage of Aboriginal blood was measured so that the government could define a person as no longer Aboriginal, but now white. In fact, as long as these people have any Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander blood in them, we will consider them Aboriginal, or Torres Strait Islander, because it’s about connection to the Nation’s land, and it’s just as much about what heritage we still have”.

- Don’t be an advocate

Let’s show respect by knowing and understanding Aboriginal culture and never speaking on behalf of Aboriginal people. In order for us to move forward in a very positive and respectful relationship with each other, it is important to listen deeply, but we can also ask questions, as long as they are respectful and come from a place of genuine interest in learning. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a deep knowledge of the land, and by passing on their stories, protocols, ceremonies, and caring for their land – the land, the sea, the waterways, and the sky – through oral traditions, we can learn a great deal about caring for the environment.

I hope that through SBS’s detailed and heart-warming tips, Chinese Australians will recognize, understand and respect Aboriginal cultures, and think about how to contribute to the realization of reconciliation and the integration of Australia’s diverse cultures and ethnicities. After all, Chinese culture is a melting pot of thousands of years of history!

You may like

Features

Chasing Speed, Chasing Risk: The Safety Myth Behind Modified E-Bike Policies

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 30, 2025

As Australia and the international community race to keep up with the green transition, a wide range of electric transport options—from electric cars to buses—have been rolled out. Among them, e-bikes have become the most widely adopted: accessible to all ages, spanning high-end to budget models, and used both publicly and privately. For many, they represent the ideal compromise between environmental responsibility and everyday convenience.

However, following a series of fires linked to modified e-bikes, the Victorian government announced that from 21 December 2025, any modified or non-compliant e-bike will be banned from trains and ticketed station areas. Factory-standard e-bikes may still be carried on trains, but they must not be charged, powered on, or ridden.

This raises a crucial question: is this new rule genuinely about protecting public safety, or is it merely a symbolic response designed to give the appearance of action?

Why Modify E-Bikes at All?

The original design philosophy behind e-bikes is fundamentally sound. They were intended as lightweight, environmentally friendly, and low-cost transport options. Compared with traditional bicycles, e-bikes require less physical effort and are particularly suitable for short urban commutes, climbing hills, or carrying loads. More importantly, they can serve as partial substitutes for cars, reducing carbon emissions and traffic congestion, while being especially accessible to the elderly, students, office workers, and people with limited mobility.

E-bikes are also meant to assist rather than fully replace pedalling, allowing riders to avoid exhaustion on long distances or steep terrain while still retaining the benefits of physical activity. In essence, their purpose is balance: safety, sustainability, and convenience working together.

Yet, as the saying goes, intentions do not always align with outcomes. Under distorted market incentives and real-world usage pressures, e-bikes have gradually drifted away from their original purpose. Modifications driven by user convenience—and impatience—have emerged as a natural consequence.

In pursuit of riding “faster and farther,” some users replace 250W motors with 500W units or install higher-capacity batteries, bypassing factory limits on power and range. Cost considerations also push those who cannot afford factory-built models to retrofit old or cheap bicycles with electric kits. Within DIY and tech-enthusiast communities, modifying e-bikes has even become a form of personal expression—an informal competition to outperform factory specifications.

But shortcuts always come at a price. The desire for speed, range, and aesthetic appeal inevitably brings increased safety risks.

The Risks of Modification—and Real-World Consequences

At its core, most e-bike modifications are carried out by hobbyists or individuals with limited technical expertise, making safety and quality highly inconsistent.

The most prominent risk lies in lithium batteries. While widely used, modified e-bikes often rely on uncertified batteries, unknown sources, or even second-hand cells. This frequently leads to mismatches between battery capacity, discharge rates, and motor demand, causing overheating. Modifications may also damage or bypass the battery’s BMS (Battery Management System), triggering thermal runaway and resulting in explosions or severe fires.

Structural limitations present another major hazard. E-bike frames and components were never designed for high power, high speed, or heavy battery loads. After modification, common issues include undersized wiring, poorly soldered connections, mismatched fuses, and incompatible chargers that introduce voltage or current errors. Frames, wheels, and braking systems originally built for human-powered cycling are suddenly forced to endure higher torque, greater speeds, and heavier loads—often without any upgrades. Modified bikes can exceed factory speed limits while retaining stock tyres, suspension, and brakes, revealing a dangerous pattern: riders overestimate their control skills while underestimating the physical limits of the vehicle.

These risks are not theoretical. On 2 September 2025, a serious house fire in Melton West was traced to a modified e-bike lithium battery that exploded while charging, reportedly upgraded to improve performance but at the cost of increased overheating risk. Earlier that year, in April and August, similar fires caused by modified e-bikes occurred at Blacktown and Liverpool train stations in New South Wales. These incidents were later cited by authorities as justification for banning modified e-bikes from trains.

A Case of Policy Misplaced Priorities

Does the introduction of new regulations mean the government is addressing the real problem? Not quite.

The government’s approach targets the most visible and easiest-to-police aspect: banning modified e-bikes from train systems, rather than confronting the underlying causes. While this may reduce fire exposure in public transport settings and allow officials to demonstrate swift action, fires do not occur because e-bikes enter trains. They occur in homes, garages, and on the street during charging.

The real danger lies not in modification itself, but in the long-standing absence of meaningful regulation over the aftermarket. High-power motors and battery kits can be easily purchased online with little to no mandatory safety testing or compliance labelling. Sellers face minimal accountability, while users bear the full risk.

Equally overlooked is the cultural shift surrounding e-bike usage. “Faster, farther, and easier” has become the primary goal for many young users seeking convenience without obtaining motorcycle licences. As a result, e-bikes are increasingly expected to perform like motorbikes, especially under pressures from urban commute times, delivery-platform economics, and social-media glorification of speed and modifications. Speed has evolved from a functional need into a status symbol. In such an environment, restricting usage locations or relying on post-incident penalties does little to reverse accumulating risk.

Lithium batteries—arguably the most critical link in the risk chain—remain poorly regulated at the import level. Without a unified certification system, users must judge compatibility on their own, and responsibility becomes impossible to trace once an accident occurs. Legal boundaries around DIY modification remain vague, reinforcing the perception that “it’s fine as long as no one catches you.” Enforcement becomes reactive, inconsistent, and scene-based rather than risk-based.

Cross-border online shopping further exacerbates the issue. Large volumes of low-cost, uncertified batteries and modification kits—often sourced from Chinese e-commerce platforms—enter Australia with inflated specifications and questionable quality. Many reuse reclaimed cells or mislabel capacity, yet evade strict inspection through small-batch or postal imports. Government oversight has lagged far behind market reality, allowing high-risk products to circulate freely. When regulation fails at the source, restricting user behaviour after accidents merely shifts responsibility onto the public.

By contrast, Canadian provinces take a fundamentally different approach. They focus on technical standards and market entry rather than usage location. Clear limits on motor power and assisted speed are enforced, while batteries and chargers must meet CSA or UL safety certifications. Vehicles exceeding these limits are reclassified as electric motorcycles, requiring registration, insurance, and compliance. Responsibility is clearly distributed among manufacturers, importers, and modifiers.

Canada addresses why fires occur. Australia focuses on where they occur.

Treating Both Symptoms and Causes

If the Australian government truly intends to reduce safety risks associated with modified e-bikes, banning them from trains is little more than a cosmetic fix. While it may reduce public exposure in the short term, it fails to address the underlying danger.

Effective policy must tackle the issue simultaneously at the source, regulatory, and educational levels.

A mandatory, unified safety certification system should be established for all e-bikes, batteries, and chargers, covering battery capacity, discharge rates, BMS integrity, and charger compatibility. Import and sales channels must be traceable, preventing high-risk products from entering the market. Modification rules must be clearly defined—what is legal, what is not—and accountability must extend to manufacturers, importers, sellers, and modifiers alike. Safe, certified upgrade pathways should exist so users are not forced into risky DIY solutions.

Education is equally critical. Through media, social platforms, public transport systems, and retail channels, users should be informed about the real dangers of battery overheating, short circuits, and structural limits, alongside their legal responsibilities. Promoting verified upgrade options and safety guidance can reduce accidents while fostering voluntary compliance.

Rather than suppressing the demand for speed, governments should regulate it. Certified upgrade standards could specify motor power, battery capacity, frame load limits, braking, and suspension requirements, allowing performance enhancements within safe boundaries. This would channel the existing “speed culture” into a controlled framework instead of letting it spiral into unregulated risk.

A longer-term solution would involve a modification registration and inspection system. Modified e-bikes that pass safety checks could receive official certification, enabling lawful use and clearer enforcement. This approach rewards compliance rather than punishing all users indiscriminately.

Finally, the issue of uncertified imported batteries must be addressed at the border. Mandatory testing, strict certification requirements, active market surveillance, and penalties for non-compliant importers and platforms are essential. A traceable responsibility chain would ensure that when accidents occur, accountability does not end with the user.

At present, Australia’s policy remains fundamentally misaligned—managing where incidents happen instead of why they happen. Without systemic reform spanning technical standards, market oversight, and user behaviour, risks will continue to migrate from trains to homes and other public spaces.

Only through comprehensive, source-based regulation can e-bikes fulfil their promise as safe, affordable, and sustainable urban transport—rather than remaining shadowed by preventable accidents.

After all, when we pursue environmental convenience while tolerating market loopholes and safety hazards, can such e-bikes truly be called transport tools that serve us?

Australia’s government has always taken pride in its multicultural society, even presenting it as a unique selling point for tourists and a beacon of hope for immigrants. Yet multiculturalism inevitably brings ideological differences, and ignoring these differences only sets the stage for tragedy.

The recent mass shooting at Bondi Beach (Hanukkah) in Sydney, which resulted in multiple deaths, prompted Australians to mourn the victims and condemn the attackers, which is a natural response. However, this tragedy also exposes a major blind spot of the Australian government: years of ignoring the steadily worsening anti-Semitism over the past two years directly contributed to this bloodshed.

Two Years of Ignored Warnings

From 2023 to 2025, anti-Semitism in Australia gradually increased, escalating from protests to arson attacks, all foreshadowing the mass shooting.

The earliest incident occurred on October 9, 2023, outside the Sydney Opera House. Approximately 500 people initially gathered at Town Hall, then marched near the Opera House, with police estimating around 1,000 attendees. The protest sparked public outrage because of the hateful slogans shouted, such as “F*** the Jews” and “Where are the Jews?” Yet, the police and government largely ignored it, underestimating the potential danger.

The hate crimes continued to escalate in 2024. On October 20, 2024, the Lewis’ Continental Kitchen in Bondi’s Curlewis Street was set on fire in the early morning hours, forcing the evacuation of residents above. This kosher family-owned restaurant had been operating for years and served the local Jewish community, who were deeply affected by the attack. In December of the same year, the Adass Israel synagogue in Melbourne was also targeted in an arson attack, causing serious damage and injuries. Although the police arrested the suspects and classified both cases as terrorist acts, the government continued to downplay their severity, with the Prime Minister merely offering verbal statements condemning racial hatred.

Subsequent anti-Jewish incidents in 2025 included two nurses in Bankstown using violent language toward Israeli patients and refusing care in February, as well as a white nationalist march in New South Wales in November, involving around 60 far-right members. The government’s response in each case was limited to verbal condemnation, brushing off the threats. Inevitably, the December Bondi Beach disaster occurred amid heightened anti-Jewish sentiment, resulting in 15 deaths and dozens injured, becoming the deadliest attack on Australia’s Jewish community in history.

The Root of the Tragedy

These successive hate-driven disasters were not random; they were a ticking time bomb fueled by specific factors.

A major cause is the oversimplification of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Certainly, Israel’s military actions in Palestinian territories, causing deaths and injuries, are excessive and worthy of criticism. But here’s the key distinction: Israel is a nation-state; its government is a political entity subject to critique. Jews are a transnational, cross-political community. The majority of Jews worldwide are not Israeli citizens, did not vote for Netanyahu, and hold diverse or even strongly oppositional views regarding Gaza.

Many people — including some politicians, academics, and social activists — reduce the world into a black-and-white dichotomy: “oppressed = absolute justice” and “powerful = original sin.” This logic leads to the dangerous equivalence: “Jews ≈ Israeli government ≈ oppressors.” In some universities and left-wing activist circles, anti-Semitism is repackaged as “anti-colonialism,” with Jewish students pressured to publicly denounce Israel to receive protection. Consequently, many non-Israeli Jews are treated as a monolithic political entity rather than a community, and their fears for personal safety — including the real risk of being attacked — are dismissed as “overreacting” or “distracting.”

Worse still, Albanese’s government, in pursuit of a superficial social harmony, chooses inaction out of political fear. To appease voters, including Muslim communities and progressive anti-war, anti-Israel constituencies, Albanese and his party sacrifice a smaller, high-risk Jewish population, offering only vague statements like “stay calm” or “both sides must respect each other.”

The fallacy lies in equating “Palestinians and Muslims have a right to be angry, so everyone deserves respect” with “these attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified by political reasons.” True freedom means no excuse can rationalize racial insults or attacks on others, regardless of cultural background. Yet government rhetoric has consistently stayed in the abstract: “I oppose all forms of hatred,” “we understand the pain and anger of communities,” or “we support peace, respect, and dialogue,” instead of clearly stating: “These attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified.” This leaves extremists free to exploit political arguments, while innocent people remain unprotected and harmed.

Ultimately, the tragedy was not caused by the government “supporting anti-Semitism,” but by political tolerance of latent hatred, systemic inertia, cultural blind spots, and the romanticization of Palestinian/Muslim anger, until the disaster exploded.

It is unfortunate that, to this day, the Prime Minister and the government have not assumed responsibility — simultaneously acknowledging Palestinian suffering while failing to enforce zero tolerance against violence and intimidation toward Jews. Politically, Albanese never directly dismantled the fallacy, instead allowing the misleading narrative: “Jews are being attacked because Israel did wrong.” This logic, if accepted, would absurdly suggest: “Russia’s invasion justifies attacks on Russian-Australians” or “China’s abuses justify threats against overseas Chinese.”

What Anti-Semitism Means

Some may think anti-Semitism only affects Jews, not other minorities. But this “mind your own business” notion is completely wrong — anti-Semitism is not just hostility toward one group; it is a society’s signal that hatred is being tolerated.

Once hatred is tolerated, it becomes a testing ground. Allowing attacks on Jews signals that people can be targeted because of their identity, faith, or heritage, stripped of basic dignity. The boundary is already broken.

The next target will never be only Jews. Today Jews may be labeled as “problematic,” “too sensitive,” or “asking for trouble”; tomorrow the same language could apply to Muslims; the day after, Asians, Africans, Indigenous people, or LGBTQ+ individuals. Hatred never needs a new reason — it just needs a precedent society permits.

As the saying goes, hatred is like a contagious disease. When exceptions are allowed, when people calculate “which minorities deserve sympathy and which can be sacrificed,” society is learning to ignore the humanity of others — a skill that will inevitably be applied to more innocent people.

Where Is Hope?

Given the despair and fear of the past two years of anti-Semitic attacks, is hope possible? Certainly. But it does not exist in political slogans or empty statements; it is embodied by those who refuse to normalize hatred.

The most immediate example is Ahmed Al-Ahmed, an Arab-Syrian Muslim who, during the Bondi Beach shooting, risked his life to stop the gunman and protect innocent Jews. Although he was shot multiple times and severely injured, he successfully disarmed the attacker and prevented more deaths. Global media praised his courage as a life-saving act. His actions shattered a persistent lie: this is not a “Jews vs. Muslims” issue, but a matter of human stance against violence and hatred.

After the Bondi Beach attack, many Sydneysiders and Melburnians held interfaith vigils and memorials. Jews, Muslims, Christians, and representatives from other communities joined, lighting candles and offering prayers. Leaders such as Bilal Rauf of the Australian National Imams Council publicly expressed mourning and support, embracing Jewish community leaders — a symbolic act of cross-cultural solidarity. Thousands more held similar ceremonies elsewhere, using silence, candles, and flowers to resist fear and hatred.

Interfaith support has appeared in other incidents as well. After the arson attack on a Melbourne synagogue last year, leaders from Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and Baha’i backgrounds came together to hold vigils and prayers, urging respect and compassion for all groups. Such collective actions reassure victims and send a strong message to society: hate will not be tolerated, and every act of solidarity is a concrete countermeasure against anti-Semitism.

Even acts less reported by mainstream media matter. Online videos showed a heavily injured pregnant woman, Jessica (Jess), shielding a 3-year-old Jewish girl with her own body, protecting her until rescuers arrived. The child’s parents later said she saved their daughter’s life, showing the importance of civilian intervention.

During the chaos, Bondi and North Bondi volunteer lifeguards rushed to aid victims before police or paramedics arrived, running through gunfire, using surfboards as stretchers, and escorting around 250 evacuees to safety. One pregnant woman even went into labor during the rescue, but volunteers ensured her safety. Their actions stabilized numerous victims and saved lives.

Looking at history, both Jews and Palestinians have endured prolonged persecution and injustice: Jews faced massacres, discrimination, and expulsion worldwide, while Palestinians suffered displacement, loss of homeland, and ongoing armed conflict. Although all sides in the Middle East conflict have made mistakes, the pain of both groups reminds us that when politics, power, and hatred dominate society, ordinary people become victims of violence and injustice.

Yet this shared suffering also offers an opportunity: if both sides can engage in dialogue based on mutual understanding and respect, without letting hatred cloud their judgment, it may be possible to overcome historical wounds and seek coexistence and reconciliation. It is in this space of rationality and empathy that society can truly learn to respect every group’s rights, without being controlled by anger and prejudice.

Ultimately, anti-Semitism is not a problem affecting only one group, but a test of society itself: who deserves protection? When the safety of any minority is relativized, everyone stands at greater risk. Yet it is precisely for this reason that empathy and courage are so crucial. Only when society draws clear and consistent boundaries — acknowledging the suffering of all groups and maintaining zero tolerance for hate and violence — does hope cease to be a slogan and become a reality that protects every individual.

Features

Examining Freedom of Speech in Hong Kong Through the Jimmy Lai Case

Published

4 weeks agoon

December 23, 2025

Jimmy Lai, the founder of Apple Daily, endured 156 days of trial under the National Security Law and was preliminarily convicted on December 15, 2025, on multiple charges, including collusion with foreign forces, publishing seditious material, and other conspiracy-related offenses.

The formal sentencing hearing will not take place until January 12, 2026, to determine the length of his imprisonment. Nevertheless, this verdict sends an undeniable signal and warning to Hong Kong residents: freedom of speech in Hong Kong is running out of time.

Freedom of Speech Is Not What It Used to Be

Since Hong Kong’s handover, the SAR government has retained much of the administrative culture and governance practices from the British colonial period. Before the enactment of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong was relatively broad. Media outlets could openly criticize officials, question policies, and publish investigative reports without immediate legal repercussions. Newspapers like Apple Daily thrived on sharp political commentary and incisive editorials; civil society and protest activities also operated within a certain degree of freedom.

Of course, freedom of speech was never absolute. Citizens still had to avoid baseless defamation or personal attacks. Overall, Hong Kong possessed a culture of debate, satire, and investigative reporting. Cartoonists could mock leaders, columnists could challenge policy decisions, and social media offered a relatively open platform for political discussion and engagement. Civil society could organize forums and large-scale peaceful marches, such as the 2003 anti-Article 23 protest that attracted 500,000 participants. The judiciary at the time was relatively independent, so criticizing officials or exposing corruption through the press did not automatically constitute a crime.

However, with the case of Jimmy Lai, the closure of Apple Daily in 2021, and the full implementation of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong has steadily declined. Media professionals, activists, and even ordinary citizens have begun to self-censor, and public discourse has visibly contracted. Hong Kong, once willing to expose wrongdoing, criticize the government, and conduct in-depth investigations, now bears little resemblance to its former self.

The Core Issues of Injustice in the Case

Under the forceful implementation of the National Security Law by the central government, the official narrative around Jimmy Lai has been uniform: “Lai sought foreign sanctions and cooperated with anti-China forces abroad,” “foreign powers glorified Lai’s actions in the name of human rights and freedom,” or “freedom of speech cannot override national security.” There is no room for debate. Nobody wants the police knocking on their door, so people naturally turn a blind eye.

But a closer analysis of the case reveals that these statements mask the deeper injustice of the crackdown on freedom of speech in Hong Kong.

First, the so-called “collusion with foreign forces” is extremely broad and vague. What exactly counts as collusion? Does speaking with foreign media qualify? The law does not clearly define the elements of “collusion,” the threshold of intent, or the degree of actual harm, allowing law enforcement and prosecution to rely heavily on after-the-fact interpretation. Ordinary public actions—such as giving interviews to foreign media, contacting overseas politicians or organizations, or calling international attention to Hong Kong’s situation—can now be reclassified as criminal acts. The core principle of the rule of law is predictability; citizens should clearly know what is legal and what is illegal. When legal boundaries are vague, people cannot adjust their behavior in advance to comply with the law, and lawful speech can be criminalized at any time, violating the fundamental judicial principle of nullum crimen sine lege (“no crime without law”).

Second, the case shows that under the National Security Law, the Chief Executive is allowed to freely select pro-Beijing judges and limit jury participation, clearly deviating from Hong Kong’s common law tradition. This blurs the line between the judiciary and the executive in politically sensitive cases. Even if a judge maintains professional integrity, the perception of independence is equally important. When politically sensitive cases are heard by executive-designated judges, defendants and the public naturally question whether the judiciary is free from political pressure. Once judicial credibility is undermined, rulings themselves are difficult to view as fully impartial, creating structural disadvantages for any defendant.

For instance, the judge stated during the trial that Lai “continued despite knowing the legal risks” and “intended to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party,” even declaring him the mastermind behind the entire conspiracy. The judgment described his use of the newspaper and personal influence as a coordinated propaganda campaign aimed at overthrowing the CCP. When the defense argued that Lai’s activities were within the scope of freedom of expression, the judge responded: “Opposing the government itself is not wrong, but if done in certain improper ways, it is wrong.” The judgment further characterized Lai’s actions as “a threat to Hong Kong and national security,” even claiming that he “sacrificed the interests of China and Hong Kong citizens.” Such politically charged language links speech directly to intent, raising doubts about judicial impartiality.

Additionally, the trial, spanning from 2023 to 2025, lasted 156 days—far beyond the original schedule. Prolonged legal procedures, combined with pre-trial detention or restrictions, caused ongoing psychological, physical, and financial pressure on Lai, particularly severe given his advanced age. His daughter, Claire Lai, stated in multiple media interviews that his health continued to deteriorate in prison, with significant weight loss and physical weakness. His son, Sebastian Lai, publicly appealed to international leaders to monitor his father’s health, fearing he might not have much time left. The prolonged trial itself constitutes an informal punishment, yet the authorities ignore the defendant’s health while asserting that the case is “lawful” and “protecting national security,” framing external criticism as foreign interference. Under this context, dissent is no longer considered part of public discourse but a potential threat, and the defendant’s human rights are irrelevant. Even before sentencing, Lai has suffered tremendous mental and physical trauma, while the prosecution, as an instrument of the state, bears no comparable burden. This asymmetry places the defense at a disadvantage and undermines the practical significance of the presumption of innocence.

Human Rights Betrayed by China

If the central government can crush a media figure simply for expressing opinions, citizens—especially the younger generation—might wish to fight back. But fantasy aside, reality must be acknowledged: Hong Kong will not allow any so-called “rebellion” to occur.

First, with the Sino-British Joint Declaration effectively undermined, the central government is no longer bound to follow the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Analysts have reasonably pointed out that the National Security Law bypasses Hong Kong’s normal legal processes, showing that the city’s once-vaunted rule of law is eroding. Once developments are circumvented in this way, the central government deems it necessary to monitor speech through ad hoc legal measures. From the arrest of activists like Miles Kwan to the prolonged trial of Jimmy Lai, dissatisfaction with policies—whether large or small—is no longer tolerated.

The ICCPR’s Article 19 protects freedom of expression, including political commentary, criticism of the government, press, publications, and international exchanges. Independent media, investigative reporting, and critical journalism are foundational to civil society’s freedom of speech. Article 14 guarantees fair trial rights, encompassing independent and impartial courts, fair bail procedures, public hearings, and the right to full defense. Yet the central government has violated both of these basic provisions. Under the National Security Law, the legal definitions of “seditious acts” and “collusion with foreign forces” are extremely vague, turning normal journalistic and public speech—comments, interviews, and international engagement—into potential criminal acts, producing a severe chilling effect. Such vagueness in law itself constitutes an infringement on freedom of expression.

Similarly, fair trial rights are compromised: judges in national security cases are designated by the Chief Executive, bail thresholds are exceptionally high, trials may occur without a jury, and Beijing retains ultimate interpretation authority. UN human rights experts widely regard political cases subject to executive influence as violating fundamental fair trial standards under international law.

Articles 21 and 22, which protect freedom of assembly and association—including peaceful protests, political organizations, and normal operation of civil groups—have also seen clear regression in Hong Kong. Numerous civil organizations have disbanded, and protests are treated as potential national security risks, with participants possibly facing retrospective criminal liability—a disproportionate and preventive restriction.

UN human rights experts, special rapporteurs, and treaty monitoring committees have repeatedly pointed out that the National Security Law’s broad definitions and implementation methods do not meet the necessity and proportionality standards required under international human rights law. The core issue is not whether the state has the right to maintain security, but whether national security is being used to completely override human rights. Rights are not gifts from the government; they are protections that cannot be arbitrarily revoked. When “national security” becomes an infinitely expandable and unquestionable rationale, rights once guaranteed under the ICCPR cease to exist legally and become political privileges revocable at any time.

How the Central Government Circumvents the ICCPR

China’s ability to bypass the ICCPR is not accidental; it stems from its historical, selective participation in the UN human rights framework. China signed the ICCPR in 1998 but has never ratified it, meaning it has never formally recognized its legal binding force domestically. Under international law, unratified treaties do not create full legal obligations for the state. Moreover, China’s “dualist” legal system requires that international treaties be transformed into domestic law to be enforceable in courts; without this, they cannot be invoked or applied in judicial proceedings.

This design allows China to diplomatically acknowledge human rights values and participate in UN discussions while retaining complete interpretive and enforcement sovereignty domestically. Even though Article 39 of the Basic Law states that the ICCPR continues to apply in Hong Kong, its practical effect is constrained by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s ultimate interpretive authority and the constitutional priority of national security. Within this structure, the common law culture and human rights protections inherited from Britain are not outright rejected but are institutionally neutralized. When the central government deems certain rights in conflict with national security, international covenants and local constitutional commitments can be reinterpreted, suspended, or effectively set aside, without immediate international legal consequences.

This institutional reality explains why Jimmy Lai gradually lost legal protection. British-established common law in Hong Kong was founded on limiting power, prioritizing individual rights over the state, and judicial checks on the executive. Article 39 of the Basic Law was intended to lock in this system and the ICCPR so that post-handover Hong Kong residents would retain fundamental freedoms. However, China’s consistent refusal to ratify the ICCPR and insistence that international human rights treaties cannot override national sovereignty allows it, through NPC interpretations and the National Security Law, to nullify the covenant’s substantive force.

Jimmy Lai’s case is a concrete manifestation of this systemic shift. Activities that would have been protected—journalistic work, political commentary, international engagement—are no longer treated as protected civil rights but are redefined as security risks subject to state intervention. With Britain’s rights-centered legal culture powerless to check central authority, and the ICCPR legally unenforceable in China, Lai and all Hong Kong citizens have effectively lost the last line of institutional protection. China does not simply “violate” international human rights law; it uses institutional design and hierarchical restructuring of power to transform Hong Kong citizens’ freedoms and legal protections from inalienable rights into political privileges revocable at will.

Crucially, many Hong Kong citizens fail to recognize that the National Security Law’s revocation of freedom of speech is legally possible precisely because China has never formally recognized the ICCPR. Signing in 1998 without ratification, the ICCPR has never been incorporated into Chinese law, meaning it cannot be directly enforced in courts. Many mistakenly believe that Article 39 of the Basic Law guarantees irrevocable protection, ignoring that its practical effect is constrained by NPC interpretations and the constitutional prioritization of national security. Thus, the National Security Law, deemed to safeguard the country’s fundamental interests, reclassifies freedom of expression not as a right protected by international law but as an exception fully limited for security reasons. This is the harsh reality that citizens still hoping for “protection under international law” have yet to fully grasp.

Lessons from the Jimmy Lai Case

Jimmy Lai’s case transcends individual criminal liability or a single judicial ruling; it symbolizes a systemic transformation in Hong Kong. In a city that was once legally bound by the ICCPR, a media founder has been convicted for his journalistic stance, political commentary, and international engagement. This demonstrates that the National Security Law has effectively reshaped the boundaries of speech and the judiciary. The case reflects not merely a ruling against one defendant but a governance logic that redefines normal civic behavior as a national security risk. Under this logic, press freedom, fair trials, and civil society are no longer institutional cornerstones but variables that can be sacrificed. Lai’s trial marks a clear transition from rights protection to political permission.

In this harsh reality, leaving Hong Kong is not shirking responsibility; it is a rational choice for risk management. When institutional resistance has been criminalized, preserving personal freedom, dignity, and future prospects is often more practical than futile confrontation.

For those choosing to stay in Hong Kong, the priority is not nostalgia or sentiment but a clear-eyed recognition that Hong Kong no longer operates under the system promised by the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The city is fully integrated into China’s political and security governance framework. Within this structure, international support, foreign government statements, or UN mechanisms can offer only limited symbolic effect. This is not “foreign betrayal” but a reflection of international political realities. Residents staying must understand the choice they are making and bear the risks and restrictions of a contracting legal and civil environment.

For those considering emigration, illusions must be discarded. Certain institutional protections and freedoms once present in Hong Kong have effectively vanished and will not return simply because of personal desire. Those who ultimately stay must accept living in a society where speech, organization, and political participation are tightly constrained. For undecided individuals, the Jimmy Lai case is an unavoidable benchmark for careful consideration. It clearly defines the boundaries of systemic risk, and making the decision to leave at this stage is not yet too late.

For Hongkongers already abroad, the next challenge is not only to mourn what Hong Kong has lost but to rebuild life, identity, and future on new soil. Only then can leaving be more than retreat, instead becoming genuine rebirth and forward movement.

Listen Now

Scam Kingpin Chen Zhi Arrested in Cambodia and Extradited to China

Severe Wildfires Spread Across Southeastern Australia, Victoria Declares Disaster

Iran Government Nationwide Internet Shutdown, Starlink Blocked

Trump’s Arrest of Maduro Sparks Congressional Opposition

Chasing Speed, Chasing Risk: The Safety Myth Behind Modified E-Bike Policies

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

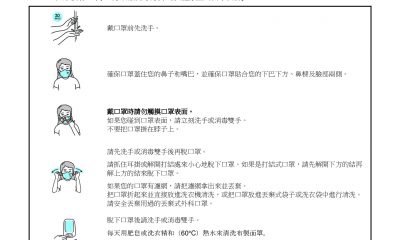

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單