Features

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (HKASPDMC)’s refusal to hand over information The Court of Final Appeal (CFA) overturned the trial judgment

Published

10 months agoon

“A “woman” cannot be interpreted as someone who “reasonably believes” that she is a woman, and a deer cannot become a horse because someone “reasonably believes” that it is a horse” – Tonyee Chow Hang-tung, arguing in the appeal to the Court of Final Appeal.

“Some people may say that the king’s lack of clothes is obvious to everyone, so what difference does it make whether or not it is said? … If we want to see changes in the outside world, we cannot remain unaware of them.”

“We must continue to burst the lies of power.” ‘No matter how many bubbles of lies, they are still fragile.’ ”It is not impossible to win, even if we have to pay a price.” — Written speech by Tonyee Chow Hang-tung

Introduction: Dissolved Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (HKASPDMC) Accused of Two Offenses

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, or the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (HKASPDMC) for short, is a former pan-democratic political organization in Hong Kong. It was founded on May 21, 1989, in the midst of the global Chinese mass rally in support of the 1989 pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong. From 1990 to 2019, the HKASPDMC has been organizing the June Fourth Rally and the Victoria Park Candlelight Vigil for 30 consecutive years to commemorate the June Fourth Incident and to express its insistence on the protection of China. For the first 22 years of its existence, the HKASPDMC was chaired by Mr. Szeto Wah, who was regarded as a lifelong patriot.

On August 25, 2021, the National Security Bureau of the police wrote to the Standing Committee and the person-in-charge of the HKASPDMC, stating that based on the police investigation, the Commissioner of Police had reasonable grounds to believe that the HKASPDMC was an “agent of a foreign country”, and requesting the HKASPDMC to submit the information and the relevant supporting documents to the Police Headquarters in writing, in person and in accordance with the requirements of the 5th Schedule of the 43rd Schedule of the Hong Kong National Security Law, within 14 days (September 7th).

On September 7, four members of the Standing Committee of the HKASPDMC submitted a letter to the Police Headquarters in Wan Chai, explaining their refusal to submit information on the membership and finances of the HKASPDMC as requested by the Police’s National Security Bureau. In its reply to the Police, the HKASPDMC said that the HKASPDMC was not a “foreign agent” and the Police had no right to request the HKASPDMC to provide the information. The HKASPDMC also considered that the Police had committed a legal error in requesting the HKASPDMC to provide the information, and was dissatisfied that the Police had not provided any justification for the refusal in the letter, which was considered to be a violation of the principle of natural justice.

On September 8, the Vice-Chairman of the HKASPDMC, Ms. Tonyee Chow Hang-tung, and members of the Standing Committee, Mr. Leung Kam-wai, Mr. Tang Ngok-kwan and Mr. Chan To-wai, were arrested by the Police National Security Bureau (NSB) at different locations in the morning and detained for investigation. Four of them were detained for investigation. Later, together with Tsui Hon-kwong, five people were charged.

On September 25, 2021, the EGM passed a resolution to dissolve the organization.

Subsequently, Leung Kam Wai and Chan To Wai, who had already been imprisoned for more than the maximum sentence for the alleged offense, pleaded guilty and were sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and released immediately. Tonyee Chow Hang Tung, Tang Ngok Kwan and Tsui Hon Kwong pleaded not guilty and were convicted on March 11, 2023 and sentenced to four and a half months’ imprisonment. Their appeals to the High Court were dismissed and they finally appealed to the Court of Final Appeal.

At present, the HKASPDMC, Lee Cheuk-yan, Albert Ho and Tonyee Chow Hang-tung are still being prosecuted for one count of “inciting subversion of state power”. The case has been referred to the High Court, and the trial date is tentatively set for May 6 this year, but the court said it may be postponed due to the judge’s lack of time to hear the case.

A Rare Small Victory

The HKASPDMC’s refusal to hand over information was unanimously ruled in favor of its appeal by the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (CFA) on June 6, with the convictions of Tonyee Chow Hang-tung, then vice-chairman of the HKASPDMC, and two former members of the Standing Committee of the HKASPDMC, namely, Tang Yuek-kwan and Tsui Hon-kwong, being quashed. The three were originally convicted and jailed for refusing to submit information about the organization to the police and were charged with violating the implementation details of the Hong Kong National Security Law. This is the first time that a case involving the Hong Kong National Security Law has been won at the Court of Final Appeal and the convictions quashed, a rare victory for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp.

The first case involving the implementation details of the Hong Kong National Security Law.

The HKASPDMC, famous for hosting the annual June 4 Candlelight Vigil in remembrance of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident, was disbanded in 2021 under the shadow of China’s enactment and full implementation of the Hong Kong National Security Law. Prior to its dissolution, the Hong Kong police’s National Security Bureau demanded that the organization provide information on its operations and finances, such as its members and donors, and accused it of being a “foreign agent” and of receiving HK$20,000 from an unnamed organization on suspicion of having ties to an overseas pro-democracy group. However, the HKASPDMC refused to cooperate, arguing that the authorities had arbitrarily labeled pro-democracy organizations as foreign agents and had no right to request information from them.

In March 2023, the Hong Kong Court of Appeal in West Kowloon stated that based on the background of the Alliance, the activities it organized and its relationship with people in Hong Kong and overseas over the past years, the Police had reasonable grounds to believe that the Alliance was a foreign agent. The judge found all the defendants guilty of the charge, as he considered that the activists were obliged to comply with the notification requirement to provide information, but did not intend to do so. But now, two years later, five judges of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal have unanimously held that the prosecution’s actions had “denied the defendants a fair trial” and ruled against the Department of Justice, which prosecuted on behalf of the Government.

In their judgment, the five Hong Kong CFA judges, headed by Chief Justice Andrew Cheung, said that the prosecution’s removal from evidence of the only material that would have established that the Alliance was a foreign agent was counterproductive to the prosecution’s case and “deprived the appellants of their right to a fair trial, resulting in their conviction involving an unfair trial”. Specifically, the Department of Justice had to prove that the HKASPDMC was in fact an “agent of a foreign state”, and the invocation of “public interest immunity” to substantially cover up the NSA’s investigation report denied the defendant access to the prosecution’s case, deprived him of his right to a fair trial, and rendered the Department of Justice’s conviction unsafe without any evidence to substantiate its case.

The Court also pointed out that the trial magistrate, Mr. Justice Lo Tak Chuen, had emphasized that in order to “effectively” safeguard national security, it was sufficient for the police to have reasonable grounds to believe that the HKASPDMC was an agent, and that the High Court Judge, Ms. Justice Lai Yuen Kei, had further ruled on appeal that the Defendant was unable to challenge the validity of the police notification letter, and that the ruling of the High Court Judge was wrong in both cases. The Court of Final Appeal pointed out that the courts could not ignore the protection of rights in the discharge of their duty to safeguard national security. This is the first time that a national security defendant has been acquitted in a final judgment. In the past, the Court of Final Appeal has lost national security cases, including the bail case of Jimmy Lai, the bail case of the defendant in the “Guardians of the Sheep Village” case, and the case of Lui Sai-yu’s commutation of sentence. Before leaving the court, Chow smiled and raised the “V” sign. Outside the court, Tang said “justice lies in the hearts of the people”, while Tsui replied that “unjust incarceration is untenable”.

From an oasis of rule of law to a “police state

During a hearing at the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal in January this year, Tonyee Chow Hang-tung defended herself in court, saying that the case highlighted what a police state is, and that a police state is the result of the courts’ connivance of such abuse of power. This connivance must stop immediately. China’s state security apparatus, which has always operated largely in the shadows, has been expanded in recent years by the Communist Party as a defender against threats to Communist rule, public order and national unity. With the introduction of the Hong Kong National Security Law a few years ago, China’s police state was rightfully extended to Hong Kong, where the Chinese security agencies will not be subject to the supervision of local laws and courts.

The open and unregulated nature of the security agencies’ operations represents a significant change for Hong Kong, which has long labeled itself an oasis of law and order. Hong Kong’s national security law introduced vaguely defined offenses, such as secession and collusion, that could well have been used to stifle protests. This was also the case when, on the first full day of the law, the Hong Kong police arrested protesters as a demonstration of the new powers given to the police under the law.

Although the Court of Final Appeal overturned the original verdict, Tonyee Chow Hang-tung , Tang Yuek Kwan and Tsui Hon-kwong were sentenced to 4.5 months in prison for “failing to comply with the notification requirement for the provision of information”, and all three of them have already served their sentences. In fact, for this kind of situation where the sentence is very short and the case is still under appeal, it is entirely possible to apply for bail. However, I do not know whether it is because the application of the Hong Kong National Security Law has increased the political sensitivity of the case that bail was not granted in this case. And it seems that there is no follow-up protection for the three people who have already served their sentences, so one cannot help but ask – is justice belatedly done, or is it still justice?

The June 4 Candlelight Vigil in Victoria Park was an annual event in Hong Kong to commemorate the victims of the June 4 Incident, organized by the HKASPDMC every year from 1990 to 2019, and held at the hard-surface soccer pitch in Victoria Park. The event was once the world’s largest June 4 commemoration, with tens to hundreds of thousands of participants each year. Hong Kong used to be the only place in Chinese territory where the victims of the June 4 Tiananmen Square incident in 1989 could be publicly commemorated, but in recent years the commemoration has gone underground. Since the central government imposed national security laws on Hong Kong in 2020, almost all forms of dissent have become criminalized in the city. As of early March this year, Hong Kong authorities have arrested 320 people on charges of endangering national security, of whom 161 have been convicted.

The Future of National Security Law in Hong Kong’s Judicial Practice

As a high standard common law jurisdiction, Hong Kong should strike a reasonable balance between safeguarding national security and protecting human rights. Specifically, it should not only implement the Hong Kong National Security Law, but also respect and protect the requirements of the Basic Law and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Under common law principles, the law should be understood as a whole. Therefore, when the court interprets the elements of Schedule 5 to the legislation, it should not only consider the textual formulation of the Schedule, but should also consider the elements of Schedule 7 to the legislation where necessary and relevant. For example, in applying to the Court for an order to furnish information or produce material, the judge has to be satisfied that there are “reasonable grounds” for suspecting that a person is in possession of the information or material and that the information or material is likely to be relevant to the investigation.

Of course, the Court of Final Appeal’s ruling does not undermine the police’s investigative powers in national security cases. Even if it cannot be proved for the time being that a person or an organization belongs to “a foreign agent, a Taiwanese agent, or an agent or manager thereof”, the police can still apply to the court on the basis of “reasonable belief”, and after sufficient evidence has been provided, the court will issue an order for the provision of information or the production of materials in accordance with the law. This arrangement is in line with the propriety of the legal procedures and demonstrates the respect and protection of human rights.

Commenting on the final judgment of the case, Mr. Sun Qingnuo, Deputy Director of the Office of National Security of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, when asked whether there were loopholes in the Hong Kong National Security Law that needed to be amended, said that the Hong Kong National Security Law could be improved continuously, including through the National People’s Congress (NPC)’s interpretation of the Basic Law. On the other hand, Professor Albert Chan of the Faculty of Law of the University of Hong Kong is of the view that the case of the HKASPDMC only involves the interpretation by the Court of Final Appeal of individual provisions of the implementation details, and does not involve the interpretation of the Basic Law by NPC. Mr. Ronny Tong, a member of the Executive Council, also analyzed that an interpretation of the Basic Law by the NPC is unlikely at this stage. The SAR Government has already indicated that it will study the judgment and the relevant legal principles, and examine how to further improve the relevant legal system and enforcement mechanism, so as to more effectively prevent, stop and punish acts endangering national security, and to continue to strengthen law enforcement power.

In recent years, the Hong Kong Government has repeatedly emphasized on different occasions that safeguarding national security is a top priority for Hong Kong. The protection of national security is not a work in progress, but a work in progress. Meanwhile, the international community has never ceased to worry that the Hong Kong National Security Law will further undermine civil liberties and fundamental freedoms, and a number of international organizations have been committed to calling for the repeal of this law and for the cessation of interpreting co-operation with United Nations agencies as a threat to national security. It is conceivable that after the first final victory for the defendants of the Hong Kong National Security Law, these two forces will further tussle with each other – whether Hong Kong’s long-proud judicial independence will be reduced to a tool of the Hong Kong National Security Law, or whether this case will rekindle Hong Kong people’s hopes for the re-establishment of a civil society is still very much an unknown. This is still a big unknown.

Article/Editorial Department Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

You may like

Raymond Chow

My New Challenge

Over the past few decades, I’ve written numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics. However, last October, I decided to write a book entirely different from anything I had done before, titled Solitary but Not Isolated. I chose to publish it through crowdfunding. Readers interested in supporting this book can visit the following webpage to learn more and help make it a reality.

I attended a rooftop school in Hong Kong for primary education (a unique feature of Hong Kong in the 1960s: temporary classrooms built on top of apartment blocks in resettlement areas to accommodate children who had moved into the district). Resources were extremely limited. In sixth grade, the school principal gave me and seven other students the opportunity to post our writings on the bulletin board every two weeks for the whole school to read. This was my first experience of writing for a public audience.

In secondary school at Queen’s College, the school published the annual magazine The Yellow Dragon, the earliest and longest-running secondary school annual in Hong Kong. My writings were never published there, though my photos occasionally appeared in reports of school activities. At university, I volunteered as editor for a scholarly publication by the Science Society called Exploration, but after two or three years it was discontinued as no one wished to continue it.

During university, I studied mathematics, which required little essay writing—mostly problem-solving. After entering the field of education, I wrote numerous articles on Hong Kong education that were published in newspaper columns. Later, through curriculum development and teacher training in Hong Kong, I had the rare opportunity to write and publish mathematics textbooks spanning from Grade 1 to Form 7—something unprecedented in Hong Kong.

After moving to Australia, I served as editor of the Christian publication Living Monthly, and eventually founded Sameway magazine, which continues today. From the first issue, I wrote the opening column Words of Sameway, and over 21 years, I have written a total of 745 pieces—a record of my life.

Yet writing Solitary but Not Isolated is something I never anticipated doing since I first learned about autism decades ago. Publishing this book is closely connected to my work with Sameway. I can only say this is a new challenge given by God, a chance to take Sameway to a new stage.

Those Who Love Solitude

Solitary but Not Isolated tells the story of a person with autism. Based on her experiences, the Happy Hands Organization has developed a bilingual training program to help autistic individuals transition from school to the workplace. Launched this year, the program aims to support others in similar circumstances.

Most people with autism do not actively seek social interactions. When they do engage with strangers, they may appear difficult to connect with or communicate with, often leading to social neglect or isolation. For parents and family, this creates a lifelong burden. Even those who complete secondary or tertiary education, despite having professional knowledge, often cannot fully utilize their abilities at work because of incomplete social understanding and lack of basic communication skills. Consequently, they are frequently relegated to jobs that do not match their abilities or are assigned work requiring minimal interaction.

Western society’s understanding of autism began with the lifestyle demands of modern life, emphasizing early social engagement and learning in school. Families, having fewer children, often pay close attention to each child’s development and have higher expectations. Over the decades, understanding of autism has evolved—from viewing it as a mental illness to recognizing it as a deviation from typical personality development. Yet how society should assist their growth remains uncertain.

Decades ago, Western focus was on “treating” autism. Research into genetic, environmental, or physical causes has made limited progress. Interventions to change solitary behaviors are also limited—for example, providing speech therapy in childhood or occupational therapy for daily living skills offers only partial support. While societal acceptance and support for autistic individuals have greatly increased, parents feel that more is needed when their children enter adult life and the workforce.

In short, those inclined toward solitude still face a gap in having equal opportunities to thrive socially and professionally.

Understanding Society and the World

Many autistic individuals focus intensely on specific interests, with little experience in social relationships or current events. As adults, this often leads others to perceive them as unaware of society, or even “odd.” In workplaces, where collaboration is essential, they may face exclusion. Many end up in solitary work with minimal social interaction.

Among Chinese communities, first- or second-generation immigrants with autism often face compounded challenges due to limited knowledge of society. Parents, unfamiliar with Australian systems, cannot fully guide their children, and these high-ability individuals rarely integrate with society, limiting opportunities to demonstrate their potential.

In 2024, ABC launched The Assembly, a TV interview program where host Leigh Sales trained 15 autistic individuals to conduct interviews and produce the show. Participants significantly increased their understanding of society and the world, and their communication and social skills improved greatly.

Last year, Sameway had the opportunity to train a bilingual autistic new immigrant, successfully helping her become a magazine editor. Meanwhile, the Happy Hands Organization developed a workplace adaptation program for bilingual, high-functioning autistic individuals. Through four to six months of training, this program offers these often-overlooked individuals a chance to adapt and develop in Australia.

Thus, Sameway is not only an information platform supporting immigrant communities but also provides a development space and opportunities for those with special needs. Readers interested can contact our magazine or the Happy Hands Organization for details.

The Loneliness of Immigrants

Many immigrants arrive in Australia as adults. They often lack opportunities to understand society deeply and, due to work and life commitments, rarely have the time to engage fully with their new environment or develop close relationships with Australians. Consequently, most live within Chinese communities with similar backgrounds. Passive personalities or limited social skills often lead to intense feelings of loneliness.

Leaving their original home and social networks creates a sense of marginalization similar to that experienced by some autistic individuals. Many immigrants are willing to understand and engage with their new society but face personal limitations and a lack of proactive governmental support, leaving them unable to integrate fully into Australian life.

Chinese immigrants, in particular, may rely heavily on long-term Chinese social media and information platforms, further isolating them from the broader society. This social isolation significantly affects their participation and engagement in Australian life.

The goal of Sameway is to assist immigrants in integrating into Australia, fostering participation and engagement in society. We hope that with continued support, we can go further and achieve more.

During the Christmas and New Year period, “Sameway” relocated though only to a spot less than 100 meters across from their original office. It was a tiring task, but we have finally settled in, allowing us to take a longer break during the holiday.

However, the world still undergoes significant changes. The President of Venezuela has been forcibly taken to New York for trial, while the new leader of Venezuela is willing to govern in line with U.S. interests. The longstanding alliance between Europe and the U.S. has become history in light of the U.S. attempt to purchase Greenland. The “Board of Peace” established by Trump requests that nations place the keeping of global peace in his personal hands, but attendees at the invitation include authoritarian dictators who have initiated wars multiple times. The generation that has grown up advocating for global integration, respect for human rights, and peaceful coexistence is now at a lost and confused. Will the world revert to a chaotic state governed by the law of the jungle, where strong countries dominate weaker ones, or can humanity choose to move forward in civilization by learning mistakes from history? We truly have no sure answer.

However, it is a time where the rise of Trump and the increasing power of global far-right political forces, coupled with the internet and social media replacing traditional media as the main source of information for many people. This has led to a society overwhelmed with information and challenges in distinguishing truth from falsehood, which is equally as frightening as an era where information is blocked, preventing access to necessary knowledge.

In Australia, as a multicultural country, immigrants face significant difficulties in obtaining lifestyle information through mainstream media. I believe that to build Australia as a harmonious and cohesive society, the government must invest substantial resources to assist immigrant communities to establish high-quality and credible multicultural media, and to accelerate the integration of first-generation immigrants into society, allowing them to become a driving force in social development.

In the past year, we have strengthened the current affairs information provided on our website. In the coming year, we will focus on enhancing our information services for the Chinese community through our broadcasts and magazine publications. I hope you can support us in achieving the goal of promoting the development of the Chinese immigrant community.

Starting this year, in line with the REJOICE’s initiative for bilingual new immigrants with autism, I will be writing a brand-new column to explore this topic with the community as they navigate With the NDIS program. I hope this innovative program by the REJOICE will receive your support for promotion and development within the community.

Additionally, after three years of training aimed at encouraging seniors to use social platforms to expand their community engagement, we will take a further step this year by launching training courses to assist seniors in using artificial intelligence. Our goal is to help Chinese seniors in Australia stay up-to-date and enjoy a higher quality of life brought about by AI.

In the new year, let us work together to build a stronger local Chinese community.

Since January 20, 2025, when Trump assumed the U.S. presidency once again, domestic issues in America have been frequent and complex, but the world cannot deny that his foreign policy has reshaped the global political landscape, ushering in a new era.

Over the past year, Trump has been extremely proactive in foreign affairs—from Greenland to Venezuela—demonstrating relentless ambition to expand U.S. influence abroad, even amid controversy and the risk of destabilizing other nations.

Prelude to 2025

Let’s briefly review Trump’s major foreign policy actions in 2025.

First, his involvement in the Gaza Strip cannot be overlooked. In February 2025, he publicly stated that the U.S. would play a more active, even leading, role in the region, supporting Israel’s security needs, including strengthening border defense and intelligence sharing. He also attempted to broker ceasefire talks in the U.S.’s name, coordinating Egypt, Qatar, and other countries as intermediaries. By October, Trump personally attended a multilateral meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, pushing for a ceasefire agreement and reconstruction framework between Israel and Hamas.

While opinions on his approach were divided, with some critics arguing that direct intervention could heighten regional tensions, Trump nonetheless reaffirmed America’s influence and presence in Middle Eastern affairs.

Early in 2025, the Trump administration reviewed all foreign aid and temporarily halted military assistance to Ukraine, using it as leverage to push forward negotiations. By mid-March, following U.S.–Ukraine consultations, military and security support resumed, including air defense systems, drone technology, and financial assistance. The U.S. also advocated international sanctions against Russia, such as high-tech export restrictions and asset freezes. These actions demonstrated Trump’s support for strategic allies and further solidified U.S. influence in Europe.

While these events may seem unrelated, they set the stage for early 2026’s diplomatic developments.

The Venezuela Raid

Trump’s most notable action in January 2026 was the sudden capture (or abduction) of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife.

In fact, as early as December 1, 2025, Trump had called Maduro, demanding he step down. When Maduro refused, Trump publicly ramped up pressure in mid-to-late December, applying economic and military pressure—including blockades, intercepting suspicious ships, and bolstering military deployments—to isolate the Maduro government. He even hinted that further U.S. action might follow if Maduro continued to resist, signaling a preemptive warning.

The result: U.S. forces launched a large-scale operation codenamed “Absolute Determination”, storming Caracas, capturing Maduro and his wife, and transporting them to New York for trial. The justification cited Maduro and his inner circle’s involvement in drug trafficking and terrorism, including conspiracies to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. At the same time, Maduro’s government had close ties with China and Russia, who provided military and economic support, posing a threat to U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The operation was also seen as a move to block rival powers from gaining leverage in Venezuela. More importantly, given Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, Trump clearly aimed to reassert U.S. dominance in the hemisphere and secure economic benefits. For many Americans, the raid showcased U.S. military might, boosting Trump’s prestige and approval. True to form, Trump paid little attention to criticism, focusing instead on praise, and was visibly self-satisfied.

International reactions were strong. China and Russia immediately condemned the U.S. action, calling it a severe violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and international law. Iran and other nations with tense U.S. relations also criticized the operation as unilateralism under the guise of anti-drug and anti-terrorism efforts, destabilizing the region.

European responses were mixed. Some EU countries long critical of Maduro still expressed reservations about the U.S. bypassing international authorization for direct military action, emphasizing that even dealing with authoritarian regimes should follow international mechanisms. This tension revealed the strain Trump’s style places on traditional allies.

In Latin America, reactions were split: anti-Maduro governments and Venezuelan opposition privately supported the move as a chance to break political deadlock, while others feared overt U.S. military intervention might revive Cold War-era “Monroe Doctrine” fears, worsening regional security.

Currently, former Vice President Rodríguez serves as interim president of Venezuela, cooperating with the U.S. while maintaining loyalty to the domestic ruling class, keeping the country relatively stable. For Trump, the goal of preventing other powers from gaining influence in the Americas and securing economic gains was achieved. Many Americans saw the raid as a demonstration of military strength, reinforcing Trump’s image as a decisive leader.

Trump’s Greenland Gambit

Since 2025, Trump has repeatedly brought Greenland into the spotlight, making it one of the most challenging and controversial topics of his second term.

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is under Danish sovereignty but enjoys local autonomy. Its location between North America and Europe along the Arctic shipping route has made it strategically valuable. Previously overlooked due to extreme cold, climate change and melting ice have expanded Arctic navigation, increasing Greenland’s military and technological importance. The island also contains vast deposits of rare earth and critical minerals, essential for modern technology and defense systems.

Trump’s assertive approach clearly aimed to maximize U.S. influence over Greenland. In 2025, he publicly expressed interest in buying Greenland and urged negotiations to secure it, even hinting at military options. This escalated tensions with Denmark and Europe.

European reactions were unanimous: Greenlandic leaders stated the island is “not for sale”, and massive protests erupted in Greenland and Denmark. The UK prime minister warned Trump that high tariffs or aggression would be a grave mistake, while EU countries—including Denmark, France, Germany, and the UK—supported Danish sovereignty. Even European far-right parties, traditionally aligned with Trump, criticized his Greenland strategy as overt aggression, causing internal rifts.

At the 2026 Davos World Economic Forum, Trump and NATO Secretary-General Rutte reached a “preliminary framework” focusing on Arctic security cooperation rather than territorial control. Trump framed it as safeguarding U.S. military bases and economic interests, while Denmark retained final authority. However, Greenland’s government stressed it was not fully involved in negotiations, highlighting an ongoing tension. Analysts debate whether this is a tactical retreat or pragmatic compromise.

Even with the temporary easing of tensions, U.S.–Europe trust has been strained, showing how far-reaching Trump’s assertive diplomacy has become.

Iran Unrest and U.S. Pressure

From late December 2025, Iran experienced nationwide protests, initially triggered by economic collapse, currency devaluation, and skyrocketing living costs, evolving into broad dissatisfaction with the regime. The government’s harsh crackdown led to casualties and arrests on a scale unseen since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The U.S., which maintains heavy sanctions against Iran citing terrorism sponsorship and nuclear/military threats, seized this moment to intervene. Trump publicly announced deploying a fleet—including aircraft carriers and missile destroyers—to the Persian Gulf to deter further escalation. He emphasized a preference for avoiding force but warned of potential military action if the regime continued violent repression.

Trump also communicated with Iranian protesters via public statements and social media, encouraging demonstrations and denouncing government violence. He canceled all official diplomatic talks until Tehran ceased the crackdown. While some protesters hoped for U.S. support, the absence of direct action led to frustration and feelings of abandonment.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard leaders warned that any U.S. strike would be considered a full-scale war. Protests and anti-U.S. imagery reflected strong resistance. Intelligence reports indicating a temporary halt in state violence led Trump to consider pausing military actions while closely monitoring the situation, balancing threats with cautious observation.

Trump’s strategy combined military presence and public warnings to pressure Tehran, deter large-scale killings, and strengthen U.S. influence in the Middle East. Yet this high-risk approach also raised the possibility of miscalculations, where tensions could escalate unintentionally, making the U.S. a target for criticism and resistance.

The “Board of Peace”

Traditionally, the U.S. has been seen as the global big brother. But with China’s growing influence and global economic support programs, U.S. presidents often feel impatient with Beijing’s increasing UN sway. Trump, ambitious and assertive, sought to take matters further.

At the 2026 Davos Forum, he launched the “Board of Peace”, initially proposed to address Gaza peace but now expanded to serve as a broader global conflict mediation mechanism. The initiative leverages U.S. influence to create an alternative diplomatic platform and invites multiple countries to participate.

However, critics question whether it is more for show than genuine peacekeeping. The EU’s concern lies less with the stated goals and more with the lack of clarity: the legal status, decision-making process, funding, and international law accountability remain unspecified. Unlike multilateral bodies like the UN or OSCE, this U.S.-backed, president-driven mechanism risks becoming a coercive tool rather than a genuine mediator.

The EU fears it could undermine Europe’s long-standing role in Middle East diplomacy, forcing it from rule-maker to follower. China was excluded, reflecting Trump’s view of Beijing as a competitor, not a partner. The Board aims to present participation as a political statement, effectively creating a U.S.-led bloc in global conflict mediation.

For Australia, the Board is a hot potato. Prime Minister Albanese received an invitation but has not confirmed participation. Several NATO and EU countries have declined, while Canada was disinvited over disagreements on China policy. Thirty-plus leaders who accepted include war actors like Putin and Israel’s Netanyahu. How they could effectively promote peace remains questionable, and handling the invitation diplomatically will test Albanese’s political skill.

Trump’s Diplomatic Logic

Across Gaza, Ukraine, Venezuela, Greenland, Iran, and the Board of Peace, Trump’s strategy is consistent: proactive engagement, pressure, disruption of norms, and forcing allies and adversaries to recalculate. He eschews slow multilateral negotiations in favor of military, economic, and media leverage, coupled with highly personalized decision-making, shifting power quickly at the negotiating table.

To Trump, diplomacy is a continuous game of strategy, not merely maintaining order. He pushes situations to the edge, then retreats strategically to gain advantage. While controversial and eroding trust among allies, it successfully recenters U.S. influence.

Crucially, Trump applies pressure not only to adversaries but to allies, forcing them to demonstrate loyalty or strategic value. This increases U.S. bargaining leverage but consumes trust capital, making international relations more transactional and short-term, and setting the stage for future friction.

Costs and Risks of Assertive Diplomacy

Reliance on pressure and uncertainty may yield short-term results but risks long-term instability. Highly personalized, low-institutional approaches erode trust in rules, procedures, and multilateral cooperation. Misjudgments are more likely in opaque, high-stakes situations. Allies and adversaries may misread threats, escalating conflict even without provocation.

Trump is reshaping U.S. diplomacy from guardian of order to rewriter of order, providing tactical flexibility but weakening institutional credibility. Whether the U.S. can balance assertive pressure with sustained trust will determine its long-term global leadership.

Ultimately, Trump’s strategy may open new strategic space for the U.S. or provoke deeper backlash and confrontation. One thing is certain: the international stage in 2026 is no longer the old world, and Trump is the key variable driving this structural transformation.

Listen Now

Pro-Trump Brazilian Influencer Arrested by U.S. ICE

German Chancellor Merz Discusses “Shared Nuclear Umbrella” with European Allies

One Nation’s “Spot the Westerner” Video Condemned

Littleproud retains leadership, Sussan Ley’s position uncertain

Starmer suggests Prince Andrew testify to US Congress

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

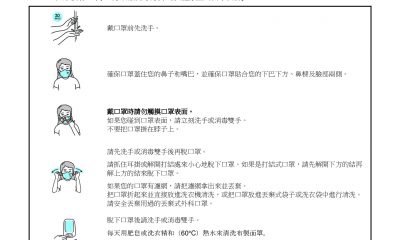

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized6 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單