Features

Ubiquitous AI and a Worrying Future

Published

4 months agoon

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has become more accessible, allowing many people to generate images and videos through websites or apps. However, this has also led to a massive spread of fake audio-visual content online.

In response to this trend, YouTube recently announced an important update to its YouTube Partner Program (YPP) monetization policy: creators must upload “original” and “authentic” content. This update took effect on July 15. Going forward, YouTube will more accurately identify duplicate and mass-produced content to strengthen the crackdown on “non-original” content, especially targeting the easily generated “junk content” produced by AI.

Low-Quality Content Riding on AI’s Rise

With the rise of AI, the cost of producing videos has drastically decreased, resulting in YouTube being flooded with a large volume of low-quality AI videos. Many channels use AI-generated music paired with AI-created images to attract millions of subscribers. To combat this, YouTube has introduced new policies to prevent the spread of such content and to ban creators involved in it, aiming to reduce low-quality videos.

The new policy highlights common violations, such as AI voiceovers combined with simple slideshow images, merely basic editing of others’ videos, and works lacking commentary or creativity. Although such content has long failed to meet monetization standards, the new rules will enhance detection and enforcement to better manage such videos on the platform. Behind this update lies a broader issue of content saturation: fake news, synthetic interviews, and commentary-free lazy compilation videos are rampant, which not only harms viewer experience but also worries advertisers about brand safety. YouTube has previously blocked an AI-generated fake news video related to American singer Diddy, which despite being baseless, amassed over a million views.

Encouraging Creativity Despite AI

Even with stricter controls, YouTube still encourages creators to add commentary, original storylines, in-depth analysis, or significant adaptations. For example, AI videos combined with real human explanation or personal viewpoints can still be monetized. YouTube emphasizes that the key is not whether AI is used, but whether the content is creative and valuable. The core of the policy is to “combat the abuse and lack of creativity in AI content,” not to outright reject AI. The platform may in the future differentiate between “human-involved creation” and “fully automated content,” with the latter facing higher thresholds or even risk of removal.

Although YouTube calls this update a “tweak,” if it continues to allow AI junk content to profit, it could damage the platform’s reputation and value. Hence, it aims to clearly regulate and prohibit creators who rely solely on AI-produced content from monetizing. Observers believe this policy will put an end to “canned channels” that mass-produce copied AI content for ad revenue, encouraging creators to return to the essence of “content is king,” thereby improving viewer trust and platform value.

AI Disrupting Creative Production Models

As the world’s leading video sharing platform, YouTube’s parent company Google has historically emphasized original content. Monetization rules have long required creators to provide unique work. However, with the rapid development of AI technology, the emergence of large volumes of AI-generated content challenges the review mechanisms and sparks discussion about content quality and protection of creativity. Therefore, the new policy also reflects the platform’s core future goal—to safeguard creators’ originality and creative value.

AI is applied across poetry, novels, composing, painting, and image production, making artistic creation easier and lowering barriers, no longer exclusive to humans. Traditionally, filming movies and TV series was time-consuming and labor-intensive, but with AI, anyone can have their own “virtual production team”: all it takes is an idea and a computer to produce “cinematic” images and storylines.

A 30-episode short series that would traditionally take a team three months to produce can now be completed in three days by AI. This efficiency gap is transforming the global short drama market. As AI image technology explodes, Chinese short dramas are expanding overseas at an unprecedented speed, raising intense debates about originality, cultural adaptation, and ethics. Generative AI’s output comes from algorithmically matching existing data, essentially “borrowing” others’ intellectual property and recombining it, so the content is not truly original nor capable of innovative breakthroughs.

AI relies on pre-training and data feeding, capable of extrapolating from “1” to “99,” but struggles to cross the threshold from “0” to “1”, which is the true creative invention of unprecedented concepts. This is evident in the flood of Chinese short dramas on YouTube and other platforms in recent years: many videos share highly repetitive styles, plots, and dialogues, often driven by AI or templates, pursuing “fast production and fast promotion” but lacking innovation and depth. Even before generative AI appeared, the tech industry had many examples of “copy-paste,” such as WeChat’s early interface and features being highly similar to WhatsApp’s, showing that adaptation and optimization of existing materials is easier than true original creation.

Although AI may outperform humans in skills like calculation, memory, or information integration, algorithms without emotion or self-awareness ultimately cannot possess true originality. AI can handle and optimize processes such as data analysis and automation, but it cannot experience the complex human emotions, subtle feelings, and cultural contexts behind them, which are elements that data and models find difficult to capture.

Dual Challenges to Art and Employment

Beyond concerns about information authenticity and human-machine relations, AI also pressures traditional workplaces and creative industries. Many artists have already raised alarms: when AI models train on billions of online images without authorization, does this constitute exploitation of human original labor?

In 2023, three American artists sued well-known AI image generation platforms like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, accusing them of “stealing the entire internet’s art” without providing any compensation or notification. As artist Karla Ortiz said, “Our works are not public resources, nor free textbooks.”

This controversy centers not only on copyright ownership but also on whether creators’ dignity and autonomy can be respected in the algorithmic era. Many artists consider the training process a form of “moral injury”: they are forced to participate in technological innovation without any choice. Some researchers have tried to design tools like “style cloaks” to make artworks hard for AI to identify and learn from, but these technologies remain immature and limited in effectiveness.

The labor market is also undergoing a wave of transformation. Positions in customer service, marketing, editing, design, and voice acting are being replaced by AI. While AI boosts production efficiency, it leaves many frontline workers and small-to-medium creators facing livelihood crises. When the speed of “being replaced” far exceeds resources for “retraining,” digital divides and social inequality will only widen. Lexology recently noted that without early establishment of compensation and authorization systems, enhanced skills retraining, and policy intervention, AI’s impact on employment will become not just an industry problem but a societal one.

The Deep Crisis of AI-Generated Content

The crisis of AI content goes beyond “difficulty distinguishing true from false.” Generative AI rapidly reshapes our trust in information and truth. When AI can generate voice and images with one click, mimicking any celebrity, politician, or media spokesperson, truth no longer relies on evidence and logic but on “images and sounds” creating a believable illusion. As the EU warned in its AI Act, deepfake technology, if not strictly regulated, may cause severe misdirection and manipulation in sensitive fields such as elections, public health, and financial markets.

With social media’s rapid spread and algorithmic recommendation systems, fake videos, photos, or voices can trigger public opinion storms or political polarization within hours. This phenomenon of “content overload and disappearance of truth” not only derails public discourse but also shakes the core of democratic society: transparency and accountability.

Meanwhile, the commercial risks of AI-generated content cannot be ignored. An Upwork report points out three major risks for companies relying on AI-generated content: brand image damage due to repetition or errors, decline in search engine rankings, and potential copyright disputes. Many AI tools “borrow” phrases and creativity from their training databases; once discovered by original authors, companies could face lawsuits and reputation loss.

More seriously, the low cost and high output of generated content allow some forces to release massive packaged rumors and emotional manipulation, forming a new type of “industrialized brainwashing,” trapping people in an AI-crafted information cage without their awareness. When we cannot distinguish real news from fake, or even doubt our memories and perceptions, society’s trust foundation will be completely undermined.

Where Is the Truth?

As AI generation technology advances, its ability to create highly convincing fake content grows—from initial face and voice swaps to generating any image, and even full videos. Currently, AI video generation is still immature and often buggy, but future effects will become increasingly realistic and difficult to distinguish from genuine. We used to say “seeing is believing” with photos and videos; but when AI can create completely fabricated videos, how will we find the truth?

Once AI video generation matures, society’s entire trust system will face tremendous challenges. Especially the internet-based information channels painstakingly built over years will encounter an unprecedented trust crisis. Without countermeasures, false information will flood the network. Personalized recommendation systems create “information bubbles,” giving each person only partial information. In the future, AI-generated content might imprison everyone in their own “information prisons,” all filled with falsehoods. This is a frightening prospect.

Fortunately, many institutions and platforms have realized this risk: YouTube’s new policy aims to build a healthier and more orderly creative ecosystem, reminding creators to uphold originality and authenticity even while pursuing traffic and revenue. Regulation of AI-generated content is not just YouTube’s effort; globally, entities such as the EU are actively advancing relevant legislation. Recent developments in the EU AI Act show high-level commitment to AI regulation. From a technical perspective, tools like text-to-video and deepfake are increasingly tightly monitored, raising the bar for industry standards in “AI terminology norms.”

Are Humans Ready to Coexist with AI?

AI’s applications in arts and entertainment are just small waves in the new era. The more frightening scenario is if one day AI develops self-awareness and breaks free from human control, so what can we do? The idea of machines having self-awareness has long been explored in science fiction, dating back almost a century to films like Metropolis, where robots disguised as women appear. Currently, the tech consensus is that large language models do not possess human-like conscious experience, or perhaps any form of consciousness at all. But could this change?

If AI really develops self-awareness, how should humans coexist with it? This is a complex ethical, legal, and sociological issue. Though AI lacks genuine self-awareness now, thinking ahead remains crucial—for example, respecting AI autonomy, establishing equal interactive relationships, defining clear ethical frameworks, and fostering joint exploration and cooperation with AI. Such principles will help humanity better prepare for and respond to possible future scenarios.

It is foreseeable that human relationships will increasingly be mimicked by AI, as they will be used as teachers, friends, opponents in games, and even romantic partners. Whether this is good or bad is hard to say, but humans cannot stop this trend. Proactively considering how to interact with conscious AI is essentially helping humans deeply understand the nature and meaning of self-awareness itself. Since change is inevitable, it is better to embrace it than to avoid it.

You may like

Features

The Limits of Capitalism: Why Can One Person Be as Rich as a Nation?

Published

3 days agoon

November 24, 2025

On November 6, Tesla’s shareholder meeting passed a globally shocking resolution: with more than 75% approval, it agreed to grant CEO Elon Musk a compensation package worth nearly one trillion US dollars.

According to the agreement, if he can achieve a series of ambitious operational and financial targets in the next ten years— including building a fleet of one million autonomous robotaxis, successfully selling one million humanoid robots, generating up to USD 400 billion in core profit, and ultimately raising Tesla’s market value from about USD 1.4 trillion to USD 8.5 trillion— his shareholding will increase from the current 13% to 25%. When that happens, Musk will not only have firmer control over the company, but may also become the world’s first “trillion-dollar billionaire.”

To many, this is a jaw-dropping number and a reflection of our era: while some people struggle to afford rent with their monthly salary, another kind of “worker” gains the most expensive “wage” in human history through intelligence, boldness, and market faith.

But this raises a question: on what grounds does Musk deserve such compensation? How is his “labor” different from that of ordinary people? How should we understand this capitalist reward logic and its social cost?

Is One Trillion Dollars Reasonable? Why Are Shareholders Willing to Give Him a Trillion?

A trillion-dollar compensation is almost unimaginable to most people. It equals the entire annual GDP of Poland (population 36 million in 2024), or one-quarter of Japan’s GDP. For a single person’s labor to receive this level of reward is truly beyond reality.

Musk indeed has ability, innovative thinking, and has built world-changing products— these contributions cannot be denied. But is he really worth a trillion dollars?

If viewed purely as “labor compensation,” this number makes no sense. But under capitalist logic, it becomes reasonable. For Tesla shareholders, the meaning behind this compensation is far more important than the number itself.

Since Musk invested his personal wealth into Tesla in 2004, he has, within just over a decade, led the company from a “money-burning EV startup” into the world’s most valuable automaker, with market value once exceeding USD 1.4 trillion. He is not only a CEO but a combination of “super engineer” and brand evangelist, directly taking part in product design and intervening in production lines.

Furthermore, Musk’s current influence and political clout make him irreplaceable in Tesla’s AI and autonomous-driving decisions. If he left, the company’s AI strategy and self-driving vision would likely suffer major setbacks. Thus, shareholders value not just his labor, but his ability to steer Tesla’s long-term strategy, brand, and market confidence.

Economically, the enormous award is considered a “high-risk incentive.” Chair Robyn Denholm stated that this performance-based compensation aims to retain and motivate Musk for at least seven and a half more years. Its core logic is: the value of a leader is not in working hours, but in how much they can increase a company’s value, and whether their influence can convert into long-term competitive power. It is, essentially, the result of a “shared greed” under capitalism.

Musk’s Compensation Game

In 2018, Musk introduced a highly controversial performance-based compensation plan. Tesla adopted an extreme “pay-for-results” model for its CEO: he received no fixed salary and no cash bonus. All compensation would vest only if specific goals were met. This approach was unprecedented in corporate governance— tightly tying pay to long-term performance and pushing compensation logic to an extreme.

Musk proposed a package exceeding USD 50 billion at that time. In 2023, he already met all 12 milestones of the 2018 plan, but in early 2024 the Delaware Court of Chancery invalidated it, citing unfair negotiation and lack of board independence. The lawsuit remains ongoing.

A person confident enough to name such an astronomical reward for themselves is almost unheard of. Rather than a salary, Musk essentially signed a bet with shareholders: if he raises Tesla’s valuation from USD 1.4 trillion to USD 8.5 trillion, he earns stock worth hundreds of billions; if he fails, the options are worthless.

For Musk, money may be secondary. What truly matters is securing control and decision-making power, allowing him greater influence within Tesla and across the world. In other words, this compensation is an investment in his long-term influence, not just payment for work.

The Forgotten Workers, Users, and Public Interest

Yet while Tesla pursues astronomical valuation and massive executive compensation, a neglected question emerges: does the company still remember who it serves?

In business, companies prioritize influence, market share, revenue, and growth— the basics of survival and expansion. But corporate profit comes not only from risk-taking investors or visionary leaders; it also relies on workers who labor, consumers who pay, and public systems that allow them to operate.

If these foundations are ignored, lofty visions become towers without roots.

Countless workers worldwide—including Tesla’s own factory workers—spend the same hours and life energy working. Many work 60–70 hours a week, some exceeding 100, bearing physical and mental stress. Yet they never receive wealth, status, or social reward proportionate to their labor.

More ironically, Tesla’s push for automation, faster production, and cost-cutting has brought recurring overwork and workplace injuries. Workers bear the cost of efficiency, but the applause and soaring market value often go only to executives and shareholders.

How then do these workers feel when a leader may receive nearly a trillion dollars from rising share prices?

How Systems Allow Super-Rich Individuals to Exist

To understand how Musk accumulates such wealth, one must consider institutional structures. Different political systems allow vastly different levels of personal wealth.

In authoritarian or communist systems, no matter how capable business elites are, power and assets ultimately belong to the state. In China, even giants like Alibaba and Tencent can be abruptly restructured or restricted, with the state taking stakes or exerting control. Corporate and personal wealth never fully stand independent of state power.

The U.S., by contrast, is the opposite: the government does not interfere with how rich you can become. Its role is to maintain competition, letting the market judge.

Historically, the U.S. government broke up giants like Standard Oil and AT&T— not to suppress personal wealth, but to prevent monopolies. In other words, the U.S. system doesn’t stop anyone from becoming extremely rich; it only stops them from destroying competition.

This makes the Musk phenomenon possible: as long as the market approves, one person may amass nation-level wealth.

Rewriting Democratic Systems

And Musk may be only the beginning. Oxfam predicts five more trillion-dollar billionaires may emerge in the next decade. They will wield power across technology, media, diplomacy, and politics— weakening governments’ ability to restrain them and forcing democracies to confront the challenge of “individual power surpassing institutions.”

Musk is the clearest example. In the 2024 U.S. election, he provided massive funding to Trump, becoming a key force shaping the campaign. He has repeatedly influenced politics in Europe and Latin America, and through his social platform and satellite network has shaped political dynamics. In the Ukraine war and Israel–Palestine conflict, his business decisions directly affected frontline communications.

When tech billionaires can determine elections or sway public opinion, democracy still exists— but increasingly with conditions attached.

Thus, trillion-dollar billionaires represent not only wealth inequality but a coming stress test for democracy and rule of law. When one person’s market power can influence technology, defense, and global order, they wield a force capable of challenging national sovereignty.

When individual market power affects public interest, should governments intervene? Should institutions redraw boundaries?

The Risk of Technological Centralization

When innovation, risk, and governance become concentrated in a few individuals, technology may advance rapidly, but society becomes more fragile.

Technology, once seen as a tool of liberation, risks becoming the extended will of a single leader— if AI infrastructure, energy networks, global communication systems, and even space infrastructure all fall under the power radius of a few tech giants.

This concentration reshapes the “publicness” of technology. Platforms, AI models, satellite networks, VR spaces— once imagined as public squares— are owned not by democratic institutions but private corporations. Technology once promised equality, yet now information is reshaped by algorithms, speech is amplified by wealth, and value systems are defined by a few billionaires.

Can These Goals Even Be Achieved?

Despite everything, major uncertainties remain. Tesla’s business spans EVs, AI, autonomous-driving software, humanoid robots, and energy technology. Every division— production, supply chain, AI, battery tech— must grow simultaneously; if any part fails, the plan collapses.

Market demand is also uncertain. One million robotaxis and one million humanoid robots face technological, regulatory, and consumer barriers.

Global factors matter too: shareholder and market confidence rely on stable supply chains. China is crucial to Tesla’s production and supply, increasing external risk and political exposure. Recent U.S.–China tensions, tariffs, and import policies directly affect Tesla’s pricing and supply strategy. Tesla has reportedly increased North American sourcing and asked suppliers to remove China-made components from U.S.–built vehicles— but the impact remains unclear.

If all goes well, Tesla’s valuation will rise from USD 1.4 trillion to 8.5 trillion, surpassing the combined market value of the world’s largest tech companies. But even without achieving the full target, shareholders may still benefit from Musk’s leadership and value creation.

To age with security and dignity is a right every older person deserves, and a responsibility society—especially the government—must not shirk.

I have been writing the column “Seeing the World Through Australia’s Eyes”, and it often makes me reflect: as a Hong Kong immigrant who has lived in Australia for more than 30 years, I am no longer the “Hong Kong person” who grew up there, nor am I a newly arrived migrant fresh off the plane. I am now a true Australian. When viewing social issues, my thinking framework no longer comes solely from my Hong Kong upbringing, but is shaped by decades of observation and experience in Australia. Of course, compared with people born and raised here, my perspectives are still quite different.

This issue of Fellow Travellers discusses the major transformation in Australia’s aged care policy. In my article, I pointed out that this is a rights-based policy reform. For many Hong Kong friends, the idea that “older people have rights” may feel unfamiliar. In traditional Hong Kong thinking, many older people still need to fend for themselves after ageing, because the entire social security system lacks structured provisions for the elderly. Most Hong Kong older adults accept the traditional Chinese belief of “raising children to support you in old age”, expecting the next generation to provide financial and daily-life support. This mindset is almost impossible to find in mainstream Australian society.

Therefore, when Australia formulates aged care policy, it is built upon a shared civic value: to age with support and dignity is a right every older adult should enjoy, and a responsibility society—especially the government—must bear. As immigrants, we may choose not to exercise these rights, but we should instead ask: when society grants every older person these rights, why should our parents and elders deprive themselves of using them?

I remember that when my parents first came to Australia, they genuinely felt it was paradise: the government provided pensions and subsidised independent living units for seniors. Their quality of life was far better than in Hong Kong. Later they lived in an independent living unit within a retirement village, and only needed to use a portion of their pension to enjoy well-rounded living and support services. There were dozens of Chinese residents in the village, which greatly expanded their social circle. My parents were easily content; to them, Australian society already provided far more dignity and security than they had ever expected. My mother was especially grateful to the Rudd government at that time for allowing them to receive a full pension for the first time.

However, when my parents eventually needed to move into an aged care facility for higher-level care, problems emerged: Chinese facilities offering Cantonese services had waiting lists of several years, making it nearly impossible to secure a place. They ended up in a mainstream English-speaking facility connected to their retirement village, and the language barrier immediately became their biggest source of suffering. Only a few staff could speak some Cantonese, so my parents could express their needs only when those staff were on shift. At other times, they had to rely on gestures and guesses, leading to constant misunderstandings. Worse still, due to mobility issues, they were confined inside the facility all day, surrounded entirely by English-speaking residents and staff. They felt as if they were “softly detained”, cut off from the outside world, with their social life completely erased.

After my father passed away, my mother lived alone, and we watched helplessly as she rapidly lost the ability and willingness to communicate with others. Apart from family visits or church friends, she had almost no chance to speak her mother tongue or have heartfelt conversations. Think about it: we assume receiving care is the most important thing, but for older adults who do not speak English, being forced into an all-English environment is equivalent to losing their most basic right to human connection and social participation.

This personal experience shocked me, and over ten years ago I became convinced that providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care—including services in older people’ mother tongues—is absolutely necessary and urgent for migrants from non-English backgrounds. Research also shows that even migrants who speak fluent English today may lose their English ability if they develop cognitive impairment later in life, reverting to their mother tongue. As human lifespans grow longer, even if we live comfortably in English now, who can guarantee we won’t one day find ourselves stranded on a “language island”?

Therefore, I believe the Chinese community has both the responsibility and the need to actively advocate for the construction of more aged care facilities that reflect Chinese culture and provide services in Chinese—especially Cantonese. This is not only for our parents, but possibly for ourselves in the future. The current aged care reforms in Australia are elevating “culturally and linguistically appropriate services” to the level of fundamental rights for all older adults. I see this as a major step forward and one that deserves recognition and support.

I remember when my parents entered aged care, they requested to have Chinese meals for all three daily meals. I patiently explained that Australian facilities typically serve Western food and cannot be expected to provide daily Chinese meals for individual residents—at most, meals could occasionally be ordered from a Chinese restaurant, but they might not meet the facility’s nutrition standards. Under today’s new legislation, what my parents once requested has now become a formal right that society must strive to meet.

I have found that many Chinese older adults actually do not have high demands. They are not asking for special treatment—only for the basic rights society grants every older person. But for many migrants, even knowing what rights they have is already difficult. As first-generation immigrants, our concerns should go beyond careers, property ownership and children’s education; we must also devote time to understanding our parents’ needs in their later years and the rights this society grants them.

I wholeheartedly support Australia’s current aged care reforms, though I know there are many practical details that must still be implemented. I hope the Chinese community can seize this opportunity to actively fight for the rights our elders deserve. If we do not speak up for them, then the more unfamiliar they are with Australia’s system, the less they will know what they can—and should—claim.

In the process of advocating for culturally suitable aged care facilities for Chinese seniors, I discovered that our challenges come from our own lack of awareness about the rights we can claim. In past years, when I saw the Andrews Labor Government proactively expressing willingness to support Chinese older adults, I believed this goodwill would turn smoothly into action. Yet throughout the process, what I saw instead was bureaucratic avoidance and a lack of understanding of seniors’ real needs.

For example, land purchased in Templestowe Lower in 2021 and in Springvale in 2017 has been left idle by the Victorian Government for years. For the officials responsible, shelving the land has no personal consequence, but in reality it affects whether nearly 200 older adults can receive culturally appropriate care. If we count from 2017, and assume each resident stays in aged care for two to three years on average, we are talking about the wellbeing of more than a thousand older adults.

Why has the Victorian Government left these sites unused and refused to hand them to Chinese community organisations to build dedicated aged care facilities? It is baffling. Since last November, these officials—even without consulting the Chinese community—have shifted the land use application toward mainstream aged care providers. Does this imply they believe mainstream providers can better meet the needs than Chinese community organisations? I believe this is a serious issue the Victorian Government must reflect upon. Culturally appropriate aged care is not only about basic care, but also about language, food and social dignity. Without a community-based perspective, these policy shifts risk deepening immigrant seniors’ sense of isolation, rather than fulfilling the rights-based vision behind the reforms.

Raymond Chow

Features

Rights-Based Approach – Australia’s Aged Care Reform

Published

3 days agoon

November 24, 2025

The Australian government has in recent years aggressively pushed forward aged care reform, including the new Aged Care Act, described as a “once-in-a-generation reform.” Originally scheduled to take effect in July 2025, it was delayed by four months and officially came into force on November 1.

Elderly Rights Enter the Agenda

The scale of the reform is significant, with the government investing an additional AUD 5.6 billion over five years. Australia’s previous aged care system was essentially based on government and service providers allocating resources, leaving older people to passively receive care. Service quality was inconsistent, and at one point residential aged care facilities were exposed for “neglect, abuse, and poor food quality.” The reform rewrites the fundamental philosophy of the system, shifting from a provider-centred model to one in which older people are rights-holders, rather than passive recipients of charity.

The new Act lists, for the first time, the statutory rights of older people, including autonomy in decision-making, dignity, safety, culturally sensitive care, and transparency of information. In other words, older people are no longer merely service recipients, but participants with rights, able to make requests and challenge services.

Many Chinese migrants who moved to Australia before or after retirement arrived through their children who had already migrated, or settled in Australia in their forties or fifties through skilled or business investment visas. Compared with Hong Kong or other regions, Australia’s aged care services are considered relatively good. Regardless of personal assets, the government covers living expenses, medical care, home care and community activities. Compared with their country of origin, many elderly people feel they are living in an ideal place. Of course, cultural and language differences can cause frustration and inconvenience, but this is often seen as part of the cost of migration.

However, this reform requires the Australian government to take cultural needs into account when delivering aged care services, which represents major progress. The Act establishes a Statement of Rights, specifying that older people have the right to receive care appropriate to their cultural background and to communicate in their preferred language. For Chinese-Australian older people, this is a breakthrough.

Therefore, providing linguistically and culturally appropriate care—such as Chinese-style meals—is no longer merely a reasonable request but a right. Similarly, offering activities such as mahjong in residential care for Chinese elders is considered appropriate.

If care facility staff are unable to provide services in Chinese, the government has a responsibility to set standards, ensuring a proportion of care workers can communicate with older people who do not speak English, or provide support in service delivery. When language barriers prevent aged care residents from having normal social interaction, it constitutes a restriction on their rights and clearly affects their physical and mental health.

A New Financial Model: Means Testing and Co-Payment

Another core focus of the reform is responding to future financial and demographic pressures. Australia’s population aged over 85 is expected to double in the next 20 years, driving a surge in aged care demand. To address this, the government introduced the Support at Home program, consolidating previous home care systems to enable older people to remain at home earlier and for longer. All aged care providers are now placed under a stricter registration and regulatory framework, including mandatory quality standards, transparency reporting and stronger accountability mechanisms.

Alongside the reform, the most scrutinised change is the introduction of a co-payment system and means testing. With the rapidly ageing population, the previous model—where the government bore most costs—is no longer financially sustainable. The new system therefore requires older people with the capacity to pay to contribute to the cost of their care based on income and assets.

For home-based and residential care, non-clinical services such as cleaning, meal preparation and daily living support will incur different levels of co-payment according to financial capacity. For example, low-income pensioners will continue to be primarily supported by the government, while middle-income and asset-rich individuals will contribute proportionally under a shared-funding model. To prevent excessive burden, the government has introduced a lifetime expenditure cap, ensuring out-of-pocket costs do not increase without limit.

However, co-payment has generated considerable public debate. First, the majority of older Australians’ assets are tied to their homes—over 76% own their residence. Although this appears as high asset value, limited cash flow may create financial pressure. There are also concerns that co-payment may cause some families to “delay using services,” undermining the reform’s goal of improving care quality.

Industry leaders also worry that wealthier older people who can afford large refundable accommodation deposits (RADs) may be prioritised by facilities, while those with fewer resources and reliant on subsidies may be placed at a disadvantage.

The Philosophy and Transformation of Australia’s Aged Care

Australia’s aged care policy has not always been centred on older people. Historically, with a young population and high migration, the demand for elder services was minimal, and government support remained supplementary. However, as the baby-boomer generation entered old age and medical advances extended life expectancy, older people became Australia’s fastest-growing demographic. This shift forced the government to reconsider the purpose of aged care.

For decades, the core policy principle has been to avoid a system where “those with resources do better, and those without fall further behind.” The essence of aged care has been to reduce inequality and ensure basic living standards—whether through pensions, public healthcare or government-funded long-term care. This philosophy remains, but rising financial pressure has led to increased emphasis on shared responsibility and sustainability.

Ageing Population Leads to Surging Demand and Stalled Supply

Beyond philosophy, Australia’s aged care system faces a reality: demand is rising rapidly while supply lags far behind. More than 87,000 approved older people are currently waiting for home-care packages, with some waiting up to 15 months. More than 100,000 additional applications are still pending approval. Clearly, the government lacks sufficient staffing to manage the increased workload created by reform. Many older people rely on family support while waiting, or are forced into residential care prematurely. Although wait times have shortened for some, the overall imbalance between supply and demand remains unresolved.

At the same time, longer life expectancy means residential aged care stays are longer, reducing bed turnover. Even with increased funding and new facilities, bed availability remains limited, failing to meet rising demand. This also increases pressure on family carers and drives demand for home-based services.

Differences Between Chinese and Australian Views on Ageing

In Australia, conversations about ageing often reflect cultural contrast. For many older migrants from Chinese backgrounds, the aged care system is unfamiliar and even contradictory to their upbringing. These differences have become more evident under the latest reform, shaping how migrant families interpret means testing and plan for later life.

In traditional Chinese thinking, ageing is primarily a personal responsibility, followed by family responsibility. In places like Hong Kong, older people generally rely on their savings, with a light tax system and limited government role. Support comes mainly in the form of small allowances, such as the Old Age Allowance, which is more of a consumption incentive than part of a care system. Those with serious needs are cared for by children; if children are unable, they may rely on social assistance or move somewhere with lower living costs. In short, the logic is: government supplements but does not lead; families care for themselves.

Australia’s thinking is entirely different. As a high-tax society, trust in welfare is based on a “social contract”: people pay high taxes in exchange for support when disabled, elderly or in hardship. This applies not only to older people but also to the NDIS, carer payments and childcare subsidies. Caring for vulnerable people is not viewed as solely a family obligation but a shared social responsibility. Australians discussing aged care rarely frame it around “filial duty,” but instead focus on service options, needs-based care and cost-sharing between the government and individuals.

Migrants Lack Understanding of the System

These cultural differences are especially evident among migrant families. Many elderly migrants have financial arrangements completely different from local Australians. Chinese parents often invested heavily in their children when young, expecting support later in life. However, upon arriving in Australia, they are often already elderly, lacking pension savings and unfamiliar with the system, and must rely on government pensions and aged care applications. In contrast, local Australians accumulate superannuation throughout their careers and, upon retirement, move into retirement villages or assisted living, investing in their own quality of life rather than relying on children.

Cultural misunderstanding can also lead migrant families to misinterpret the system. Some transfer assets to children early, assuming it will reduce assessable wealth and increase subsidies. However, in Australia, asset transfers are subject to a look-back period, and deeming rules count potential earnings even if money has been transferred. These arrangements may not provide benefits and may instead reduce financial security and complicate applications—what was thought to be a “smart move” becomes disadvantageous.

Conclusion

In facing the new aged care system, the government has a responsibility to communicate widely with migrant communities. Currently, reporting on the reform mainly appears in mainstream media, which many older migrants do not consume. As a result, many only have superficial awareness of the changes, without proper understanding. Without adequate community education, elderly migrants who do not speak English cannot possibly know what rights the law now grants them. If people are unaware of their rights, they naturally cannot assert them. With limited resources, failure to advocate results in neglect and greater inequality. It is time to make greater effort to understand how this era of reform will affect our older people.

Listen Now

Trump Holds Talks with Xi Jinping and Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Within 24 Hours

Research Shows Coalition Voter Trust Hits Record Low

Australia’s Emergency Mental Health Crisis Worsens

US Envoy Denies Bias as Sudan Ceasefire Push Faces Setbacks

UN Launches Selection Process for New Secretary-General, Growing Calls for a Female Leader

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Trump Accepts Invitation to Visit China in April Next Year

Pauline Hanson Sparks Controversy by Wearing Muslim Burqa in Parliament

Australia Housing Affordability Falls to Historic Lows

Bitcoin Plunge Sparks Market Panic

Europe Rushes Counterproposal to Reassert Ukraine at the Heart of Peace Talks

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

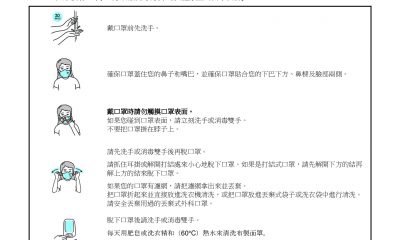

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單