Features

Beyond Bloodlines: The Interwoven Shadows and Lights of Chinese Identity in Australia

Published

4 months agoon

On July 26, 2025, ABC News published an article profiling several Chinese-Australian politicians, aiming to showcase multicultural perspectives and highlight Chinese participation in politics. Yet, upon closer reading, it contained multiple errors and oversimplifications, reflecting how Australian society still perceives “Chinese identity” only at a surface level, without grappling with its true diversity.

Misunderstandings and Overgeneralizations

The article grouped all Asian-background politicians under the label Chinese-Australian, even though some did not have direct roots in China. For example, Sally Sitou’s parents came from Laos, while Gabriel Ng was born in Malaysia. Both were identified as Chinese-Australians simply because of ethnic heritage, ignoring the vast cultural differences among Chinese diasporas. A Malaysian Chinese may speak Hokkien or Cantonese at home, use Malay in daily life, and lack proficiency in Mandarin, while their education system reflects British colonial influence — markedly different from mainland China. Reducing them all to “Chinese” erases linguistic and cultural nuance.

Even within one individual, identity is not fixed but shaped by history and experience. Former MP Meng Heang Tak, for instance, came from a Cambodian-Chinese family persecuted under the Khmer Rouge, shaping an initial distrust of China. Later, his professional dealings led to closer ties with Beijing, shifting his sense of identity. This illustrates that “Chinese identity” is fluid, multi-layered, and dynamic.

When media and politicians lump these figures together as Chinese-Australian, they risk obscuring their complex cultural and generational identities. Such simplifications are often instrumentalized in debates on Chinese influence, reinforcing stereotypes of Chinese as a homogenous and politically mobilized bloc.

A striking example is Julie-Ann Campbell, included in ABC’s list of “six Chinese-Australian MPs.” Yet her Chinese heritage comes only from her mother, with her family settled in Australia for generations. She neither practices Chinese culture nor engages closely with Chinese communities. Labeling her “Chinese-Australian” reveals a bloodline-first logic that sidelines cultural practice and self-identification. By that reasoning, millions of Anglo-Australians with English ancestry should be called “English-Australians” — though most would deny any living connection to England.

Misconceptions About Chinese Culture

While the ABC piece intended to highlight non-white representation, its missteps show how shallow the understanding of “Chinese” remains. Such portrayals may seem “normal” to mainstream readers, but they create alienation among Chinese communities, who feel misrepresented.

Ironically, similar misunderstandings exist within Chinese communities themselves. Admiration often falls on Chinese-background politicians not for cultural affinity but for power and status. Figures like Penny Wong are celebrated less as cultural kin than as symbols of prestige, reflecting a long-standing hierarchical mindset. Historical examples, such as the posthumous glorification of Genghis Khan as a “Chinese leader,” reveal this tendency to adopt powerful outsiders into a collective identity.

Moreover, the ABC’s list included few with direct roots in China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan — the largest source regions of Australia’s Chinese community. Even first-generation immigrants like Sam Lim, born in Malaysia, may feel disconnected from these groups. Such gaps went unacknowledged.

Barriers Facing Chinese Immigrants

Why are first-generation immigrants from China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan so rarely seen in politics? The core barriers lie in structural exclusion and systemic bias. Despite high education and professional skills, many face hurdles:

-

Language: English proficiency affects access to politics and public life.

-

Credential recognition: Overseas qualifications are often dismissed, sidelining professionals.

-

Political suspicion: Chinese-born Australians are subjected to scrutiny and stigma due to tense Australia-China relations, discouraging participation.

Former MP Gladys Liu exemplifies these challenges. Though her election was hailed as a multicultural milestone, she struggled with trust from both mainstream and Chinese constituencies. Her ambiguity on Hong Kong and Xinjiang issues alienated democratic-leaning Chinese while raising suspicion among others. Her eventual electoral loss revealed the inadequacy of “Chinese identity” alone as a political base.

The Real Issue

Australian society continues to conflate ethnicity with representation. Politicians with partial Chinese ancestry but little cultural engagement are easily branded as “Chinese representatives,” while first-generation immigrants who actively preserve language, traditions, and community ties remain invisible. This bloodline-based representation misplaces the essence of multiculturalism, which should emphasize lived cultural participation, not symbolic ancestry.

For genuine inclusion, Australia must:

-

Support advanced English and civic education for first-generation immigrants to empower their political voices.

-

Provide systemic recognition of foreign qualifications to reduce professional marginalization.

-

Encourage policies that respect bilingualism and cultural continuity, such as multilingual election materials and cultural advisory councils.

True multiculturalism cannot be built by tokenizing second- or third-generation “Chinese faces” for optics. It requires dismantling structural barriers that silence first-generation immigrants, allowing them to engage politically while retaining cultural identity. Only then can Chinese immigrants achieve dignity and real representation in Australian society.

You may like

Australia’s government has always taken pride in its multicultural society, even presenting it as a unique selling point for tourists and a beacon of hope for immigrants. Yet multiculturalism inevitably brings ideological differences, and ignoring these differences only sets the stage for tragedy.

The recent mass shooting at Bondi Beach (Hanukkah) in Sydney, which resulted in multiple deaths, prompted Australians to mourn the victims and condemn the attackers, which is a natural response. However, this tragedy also exposes a major blind spot of the Australian government: years of ignoring the steadily worsening anti-Semitism over the past two years directly contributed to this bloodshed.

Two Years of Ignored Warnings

From 2023 to 2025, anti-Semitism in Australia gradually increased, escalating from protests to arson attacks, all foreshadowing the mass shooting.

The earliest incident occurred on October 9, 2023, outside the Sydney Opera House. Approximately 500 people initially gathered at Town Hall, then marched near the Opera House, with police estimating around 1,000 attendees. The protest sparked public outrage because of the hateful slogans shouted, such as “F*** the Jews” and “Where are the Jews?” Yet, the police and government largely ignored it, underestimating the potential danger.

The hate crimes continued to escalate in 2024. On October 20, 2024, the Lewis’ Continental Kitchen in Bondi’s Curlewis Street was set on fire in the early morning hours, forcing the evacuation of residents above. This kosher family-owned restaurant had been operating for years and served the local Jewish community, who were deeply affected by the attack. In December of the same year, the Adass Israel synagogue in Melbourne was also targeted in an arson attack, causing serious damage and injuries. Although the police arrested the suspects and classified both cases as terrorist acts, the government continued to downplay their severity, with the Prime Minister merely offering verbal statements condemning racial hatred.

Subsequent anti-Jewish incidents in 2025 included two nurses in Bankstown using violent language toward Israeli patients and refusing care in February, as well as a white nationalist march in New South Wales in November, involving around 60 far-right members. The government’s response in each case was limited to verbal condemnation, brushing off the threats. Inevitably, the December Bondi Beach disaster occurred amid heightened anti-Jewish sentiment, resulting in 15 deaths and dozens injured, becoming the deadliest attack on Australia’s Jewish community in history.

The Root of the Tragedy

These successive hate-driven disasters were not random; they were a ticking time bomb fueled by specific factors.

A major cause is the oversimplification of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Certainly, Israel’s military actions in Palestinian territories, causing deaths and injuries, are excessive and worthy of criticism. But here’s the key distinction: Israel is a nation-state; its government is a political entity subject to critique. Jews are a transnational, cross-political community. The majority of Jews worldwide are not Israeli citizens, did not vote for Netanyahu, and hold diverse or even strongly oppositional views regarding Gaza.

Many people — including some politicians, academics, and social activists — reduce the world into a black-and-white dichotomy: “oppressed = absolute justice” and “powerful = original sin.” This logic leads to the dangerous equivalence: “Jews ≈ Israeli government ≈ oppressors.” In some universities and left-wing activist circles, anti-Semitism is repackaged as “anti-colonialism,” with Jewish students pressured to publicly denounce Israel to receive protection. Consequently, many non-Israeli Jews are treated as a monolithic political entity rather than a community, and their fears for personal safety — including the real risk of being attacked — are dismissed as “overreacting” or “distracting.”

Worse still, Albanese’s government, in pursuit of a superficial social harmony, chooses inaction out of political fear. To appease voters, including Muslim communities and progressive anti-war, anti-Israel constituencies, Albanese and his party sacrifice a smaller, high-risk Jewish population, offering only vague statements like “stay calm” or “both sides must respect each other.”

The fallacy lies in equating “Palestinians and Muslims have a right to be angry, so everyone deserves respect” with “these attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified by political reasons.” True freedom means no excuse can rationalize racial insults or attacks on others, regardless of cultural background. Yet government rhetoric has consistently stayed in the abstract: “I oppose all forms of hatred,” “we understand the pain and anger of communities,” or “we support peace, respect, and dialogue,” instead of clearly stating: “These attacks are anti-Semitic and cannot be justified.” This leaves extremists free to exploit political arguments, while innocent people remain unprotected and harmed.

Ultimately, the tragedy was not caused by the government “supporting anti-Semitism,” but by political tolerance of latent hatred, systemic inertia, cultural blind spots, and the romanticization of Palestinian/Muslim anger, until the disaster exploded.

It is unfortunate that, to this day, the Prime Minister and the government have not assumed responsibility — simultaneously acknowledging Palestinian suffering while failing to enforce zero tolerance against violence and intimidation toward Jews. Politically, Albanese never directly dismantled the fallacy, instead allowing the misleading narrative: “Jews are being attacked because Israel did wrong.” This logic, if accepted, would absurdly suggest: “Russia’s invasion justifies attacks on Russian-Australians” or “China’s abuses justify threats against overseas Chinese.”

What Anti-Semitism Means

Some may think anti-Semitism only affects Jews, not other minorities. But this “mind your own business” notion is completely wrong — anti-Semitism is not just hostility toward one group; it is a society’s signal that hatred is being tolerated.

Once hatred is tolerated, it becomes a testing ground. Allowing attacks on Jews signals that people can be targeted because of their identity, faith, or heritage, stripped of basic dignity. The boundary is already broken.

The next target will never be only Jews. Today Jews may be labeled as “problematic,” “too sensitive,” or “asking for trouble”; tomorrow the same language could apply to Muslims; the day after, Asians, Africans, Indigenous people, or LGBTQ+ individuals. Hatred never needs a new reason — it just needs a precedent society permits.

As the saying goes, hatred is like a contagious disease. When exceptions are allowed, when people calculate “which minorities deserve sympathy and which can be sacrificed,” society is learning to ignore the humanity of others — a skill that will inevitably be applied to more innocent people.

Where Is Hope?

Given the despair and fear of the past two years of anti-Semitic attacks, is hope possible? Certainly. But it does not exist in political slogans or empty statements; it is embodied by those who refuse to normalize hatred.

The most immediate example is Ahmed Al-Ahmed, an Arab-Syrian Muslim who, during the Bondi Beach shooting, risked his life to stop the gunman and protect innocent Jews. Although he was shot multiple times and severely injured, he successfully disarmed the attacker and prevented more deaths. Global media praised his courage as a life-saving act. His actions shattered a persistent lie: this is not a “Jews vs. Muslims” issue, but a matter of human stance against violence and hatred.

After the Bondi Beach attack, many Sydneysiders and Melburnians held interfaith vigils and memorials. Jews, Muslims, Christians, and representatives from other communities joined, lighting candles and offering prayers. Leaders such as Bilal Rauf of the Australian National Imams Council publicly expressed mourning and support, embracing Jewish community leaders — a symbolic act of cross-cultural solidarity. Thousands more held similar ceremonies elsewhere, using silence, candles, and flowers to resist fear and hatred.

Interfaith support has appeared in other incidents as well. After the arson attack on a Melbourne synagogue last year, leaders from Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and Baha’i backgrounds came together to hold vigils and prayers, urging respect and compassion for all groups. Such collective actions reassure victims and send a strong message to society: hate will not be tolerated, and every act of solidarity is a concrete countermeasure against anti-Semitism.

Even acts less reported by mainstream media matter. Online videos showed a heavily injured pregnant woman, Jessica (Jess), shielding a 3-year-old Jewish girl with her own body, protecting her until rescuers arrived. The child’s parents later said she saved their daughter’s life, showing the importance of civilian intervention.

During the chaos, Bondi and North Bondi volunteer lifeguards rushed to aid victims before police or paramedics arrived, running through gunfire, using surfboards as stretchers, and escorting around 250 evacuees to safety. One pregnant woman even went into labor during the rescue, but volunteers ensured her safety. Their actions stabilized numerous victims and saved lives.

Looking at history, both Jews and Palestinians have endured prolonged persecution and injustice: Jews faced massacres, discrimination, and expulsion worldwide, while Palestinians suffered displacement, loss of homeland, and ongoing armed conflict. Although all sides in the Middle East conflict have made mistakes, the pain of both groups reminds us that when politics, power, and hatred dominate society, ordinary people become victims of violence and injustice.

Yet this shared suffering also offers an opportunity: if both sides can engage in dialogue based on mutual understanding and respect, without letting hatred cloud their judgment, it may be possible to overcome historical wounds and seek coexistence and reconciliation. It is in this space of rationality and empathy that society can truly learn to respect every group’s rights, without being controlled by anger and prejudice.

Ultimately, anti-Semitism is not a problem affecting only one group, but a test of society itself: who deserves protection? When the safety of any minority is relativized, everyone stands at greater risk. Yet it is precisely for this reason that empathy and courage are so crucial. Only when society draws clear and consistent boundaries — acknowledging the suffering of all groups and maintaining zero tolerance for hate and violence — does hope cease to be a slogan and become a reality that protects every individual.

Features

Examining Freedom of Speech in Hong Kong Through the Jimmy Lai Case

Published

2 days agoon

December 23, 2025

Jimmy Lai, the founder of Apple Daily, endured 156 days of trial under the National Security Law and was preliminarily convicted on December 15, 2025, on multiple charges, including collusion with foreign forces, publishing seditious material, and other conspiracy-related offenses.

The formal sentencing hearing will not take place until January 12, 2026, to determine the length of his imprisonment. Nevertheless, this verdict sends an undeniable signal and warning to Hong Kong residents: freedom of speech in Hong Kong is running out of time.

Freedom of Speech Is Not What It Used to Be

Since Hong Kong’s handover, the SAR government has retained much of the administrative culture and governance practices from the British colonial period. Before the enactment of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong was relatively broad. Media outlets could openly criticize officials, question policies, and publish investigative reports without immediate legal repercussions. Newspapers like Apple Daily thrived on sharp political commentary and incisive editorials; civil society and protest activities also operated within a certain degree of freedom.

Of course, freedom of speech was never absolute. Citizens still had to avoid baseless defamation or personal attacks. Overall, Hong Kong possessed a culture of debate, satire, and investigative reporting. Cartoonists could mock leaders, columnists could challenge policy decisions, and social media offered a relatively open platform for political discussion and engagement. Civil society could organize forums and large-scale peaceful marches, such as the 2003 anti-Article 23 protest that attracted 500,000 participants. The judiciary at the time was relatively independent, so criticizing officials or exposing corruption through the press did not automatically constitute a crime.

However, with the case of Jimmy Lai, the closure of Apple Daily in 2021, and the full implementation of the National Security Law, freedom of speech in Hong Kong has steadily declined. Media professionals, activists, and even ordinary citizens have begun to self-censor, and public discourse has visibly contracted. Hong Kong, once willing to expose wrongdoing, criticize the government, and conduct in-depth investigations, now bears little resemblance to its former self.

The Core Issues of Injustice in the Case

Under the forceful implementation of the National Security Law by the central government, the official narrative around Jimmy Lai has been uniform: “Lai sought foreign sanctions and cooperated with anti-China forces abroad,” “foreign powers glorified Lai’s actions in the name of human rights and freedom,” or “freedom of speech cannot override national security.” There is no room for debate. Nobody wants the police knocking on their door, so people naturally turn a blind eye.

But a closer analysis of the case reveals that these statements mask the deeper injustice of the crackdown on freedom of speech in Hong Kong.

First, the so-called “collusion with foreign forces” is extremely broad and vague. What exactly counts as collusion? Does speaking with foreign media qualify? The law does not clearly define the elements of “collusion,” the threshold of intent, or the degree of actual harm, allowing law enforcement and prosecution to rely heavily on after-the-fact interpretation. Ordinary public actions—such as giving interviews to foreign media, contacting overseas politicians or organizations, or calling international attention to Hong Kong’s situation—can now be reclassified as criminal acts. The core principle of the rule of law is predictability; citizens should clearly know what is legal and what is illegal. When legal boundaries are vague, people cannot adjust their behavior in advance to comply with the law, and lawful speech can be criminalized at any time, violating the fundamental judicial principle of nullum crimen sine lege (“no crime without law”).

Second, the case shows that under the National Security Law, the Chief Executive is allowed to freely select pro-Beijing judges and limit jury participation, clearly deviating from Hong Kong’s common law tradition. This blurs the line between the judiciary and the executive in politically sensitive cases. Even if a judge maintains professional integrity, the perception of independence is equally important. When politically sensitive cases are heard by executive-designated judges, defendants and the public naturally question whether the judiciary is free from political pressure. Once judicial credibility is undermined, rulings themselves are difficult to view as fully impartial, creating structural disadvantages for any defendant.

For instance, the judge stated during the trial that Lai “continued despite knowing the legal risks” and “intended to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party,” even declaring him the mastermind behind the entire conspiracy. The judgment described his use of the newspaper and personal influence as a coordinated propaganda campaign aimed at overthrowing the CCP. When the defense argued that Lai’s activities were within the scope of freedom of expression, the judge responded: “Opposing the government itself is not wrong, but if done in certain improper ways, it is wrong.” The judgment further characterized Lai’s actions as “a threat to Hong Kong and national security,” even claiming that he “sacrificed the interests of China and Hong Kong citizens.” Such politically charged language links speech directly to intent, raising doubts about judicial impartiality.

Additionally, the trial, spanning from 2023 to 2025, lasted 156 days—far beyond the original schedule. Prolonged legal procedures, combined with pre-trial detention or restrictions, caused ongoing psychological, physical, and financial pressure on Lai, particularly severe given his advanced age. His daughter, Claire Lai, stated in multiple media interviews that his health continued to deteriorate in prison, with significant weight loss and physical weakness. His son, Sebastian Lai, publicly appealed to international leaders to monitor his father’s health, fearing he might not have much time left. The prolonged trial itself constitutes an informal punishment, yet the authorities ignore the defendant’s health while asserting that the case is “lawful” and “protecting national security,” framing external criticism as foreign interference. Under this context, dissent is no longer considered part of public discourse but a potential threat, and the defendant’s human rights are irrelevant. Even before sentencing, Lai has suffered tremendous mental and physical trauma, while the prosecution, as an instrument of the state, bears no comparable burden. This asymmetry places the defense at a disadvantage and undermines the practical significance of the presumption of innocence.

Human Rights Betrayed by China

If the central government can crush a media figure simply for expressing opinions, citizens—especially the younger generation—might wish to fight back. But fantasy aside, reality must be acknowledged: Hong Kong will not allow any so-called “rebellion” to occur.

First, with the Sino-British Joint Declaration effectively undermined, the central government is no longer bound to follow the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Analysts have reasonably pointed out that the National Security Law bypasses Hong Kong’s normal legal processes, showing that the city’s once-vaunted rule of law is eroding. Once developments are circumvented in this way, the central government deems it necessary to monitor speech through ad hoc legal measures. From the arrest of activists like Miles Kwan to the prolonged trial of Jimmy Lai, dissatisfaction with policies—whether large or small—is no longer tolerated.

The ICCPR’s Article 19 protects freedom of expression, including political commentary, criticism of the government, press, publications, and international exchanges. Independent media, investigative reporting, and critical journalism are foundational to civil society’s freedom of speech. Article 14 guarantees fair trial rights, encompassing independent and impartial courts, fair bail procedures, public hearings, and the right to full defense. Yet the central government has violated both of these basic provisions. Under the National Security Law, the legal definitions of “seditious acts” and “collusion with foreign forces” are extremely vague, turning normal journalistic and public speech—comments, interviews, and international engagement—into potential criminal acts, producing a severe chilling effect. Such vagueness in law itself constitutes an infringement on freedom of expression.

Similarly, fair trial rights are compromised: judges in national security cases are designated by the Chief Executive, bail thresholds are exceptionally high, trials may occur without a jury, and Beijing retains ultimate interpretation authority. UN human rights experts widely regard political cases subject to executive influence as violating fundamental fair trial standards under international law.

Articles 21 and 22, which protect freedom of assembly and association—including peaceful protests, political organizations, and normal operation of civil groups—have also seen clear regression in Hong Kong. Numerous civil organizations have disbanded, and protests are treated as potential national security risks, with participants possibly facing retrospective criminal liability—a disproportionate and preventive restriction.

UN human rights experts, special rapporteurs, and treaty monitoring committees have repeatedly pointed out that the National Security Law’s broad definitions and implementation methods do not meet the necessity and proportionality standards required under international human rights law. The core issue is not whether the state has the right to maintain security, but whether national security is being used to completely override human rights. Rights are not gifts from the government; they are protections that cannot be arbitrarily revoked. When “national security” becomes an infinitely expandable and unquestionable rationale, rights once guaranteed under the ICCPR cease to exist legally and become political privileges revocable at any time.

How the Central Government Circumvents the ICCPR

China’s ability to bypass the ICCPR is not accidental; it stems from its historical, selective participation in the UN human rights framework. China signed the ICCPR in 1998 but has never ratified it, meaning it has never formally recognized its legal binding force domestically. Under international law, unratified treaties do not create full legal obligations for the state. Moreover, China’s “dualist” legal system requires that international treaties be transformed into domestic law to be enforceable in courts; without this, they cannot be invoked or applied in judicial proceedings.

This design allows China to diplomatically acknowledge human rights values and participate in UN discussions while retaining complete interpretive and enforcement sovereignty domestically. Even though Article 39 of the Basic Law states that the ICCPR continues to apply in Hong Kong, its practical effect is constrained by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s ultimate interpretive authority and the constitutional priority of national security. Within this structure, the common law culture and human rights protections inherited from Britain are not outright rejected but are institutionally neutralized. When the central government deems certain rights in conflict with national security, international covenants and local constitutional commitments can be reinterpreted, suspended, or effectively set aside, without immediate international legal consequences.

This institutional reality explains why Jimmy Lai gradually lost legal protection. British-established common law in Hong Kong was founded on limiting power, prioritizing individual rights over the state, and judicial checks on the executive. Article 39 of the Basic Law was intended to lock in this system and the ICCPR so that post-handover Hong Kong residents would retain fundamental freedoms. However, China’s consistent refusal to ratify the ICCPR and insistence that international human rights treaties cannot override national sovereignty allows it, through NPC interpretations and the National Security Law, to nullify the covenant’s substantive force.

Jimmy Lai’s case is a concrete manifestation of this systemic shift. Activities that would have been protected—journalistic work, political commentary, international engagement—are no longer treated as protected civil rights but are redefined as security risks subject to state intervention. With Britain’s rights-centered legal culture powerless to check central authority, and the ICCPR legally unenforceable in China, Lai and all Hong Kong citizens have effectively lost the last line of institutional protection. China does not simply “violate” international human rights law; it uses institutional design and hierarchical restructuring of power to transform Hong Kong citizens’ freedoms and legal protections from inalienable rights into political privileges revocable at will.

Crucially, many Hong Kong citizens fail to recognize that the National Security Law’s revocation of freedom of speech is legally possible precisely because China has never formally recognized the ICCPR. Signing in 1998 without ratification, the ICCPR has never been incorporated into Chinese law, meaning it cannot be directly enforced in courts. Many mistakenly believe that Article 39 of the Basic Law guarantees irrevocable protection, ignoring that its practical effect is constrained by NPC interpretations and the constitutional prioritization of national security. Thus, the National Security Law, deemed to safeguard the country’s fundamental interests, reclassifies freedom of expression not as a right protected by international law but as an exception fully limited for security reasons. This is the harsh reality that citizens still hoping for “protection under international law” have yet to fully grasp.

Lessons from the Jimmy Lai Case

Jimmy Lai’s case transcends individual criminal liability or a single judicial ruling; it symbolizes a systemic transformation in Hong Kong. In a city that was once legally bound by the ICCPR, a media founder has been convicted for his journalistic stance, political commentary, and international engagement. This demonstrates that the National Security Law has effectively reshaped the boundaries of speech and the judiciary. The case reflects not merely a ruling against one defendant but a governance logic that redefines normal civic behavior as a national security risk. Under this logic, press freedom, fair trials, and civil society are no longer institutional cornerstones but variables that can be sacrificed. Lai’s trial marks a clear transition from rights protection to political permission.

In this harsh reality, leaving Hong Kong is not shirking responsibility; it is a rational choice for risk management. When institutional resistance has been criminalized, preserving personal freedom, dignity, and future prospects is often more practical than futile confrontation.

For those choosing to stay in Hong Kong, the priority is not nostalgia or sentiment but a clear-eyed recognition that Hong Kong no longer operates under the system promised by the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The city is fully integrated into China’s political and security governance framework. Within this structure, international support, foreign government statements, or UN mechanisms can offer only limited symbolic effect. This is not “foreign betrayal” but a reflection of international political realities. Residents staying must understand the choice they are making and bear the risks and restrictions of a contracting legal and civil environment.

For those considering emigration, illusions must be discarded. Certain institutional protections and freedoms once present in Hong Kong have effectively vanished and will not return simply because of personal desire. Those who ultimately stay must accept living in a society where speech, organization, and political participation are tightly constrained. For undecided individuals, the Jimmy Lai case is an unavoidable benchmark for careful consideration. It clearly defines the boundaries of systemic risk, and making the decision to leave at this stage is not yet too late.

For Hongkongers already abroad, the next challenge is not only to mourn what Hong Kong has lost but to rebuild life, identity, and future on new soil. Only then can leaving be more than retreat, instead becoming genuine rebirth and forward movement.

This year, the world has continued to pass through turmoil.

Israel has temporarily stopped its attacks on Gaza. I hope that this region, after nearly 80 years of conflict, can finally move toward peace. I remember when I was young, I believed that this land was given by God to the Israelites, and therefore they had the right to kill all others in order to protect the land that belonged to them. I can only admit my ignorance. Yet this did not cause me to lose my faith; rather, it taught me to seek and understand the One I believe in amid questioning and doubt.

December is the time when we remember the birth of Jesus Christ—a season when people would bless one another. Sameway sends blessings to every reader, whether you are in Australia or gone overseas. May you experience peace that comes from God, and not only enjoy a relaxing holiday with your family, but also share quality time together. Our colleagues will also take a short break, and we will resume publication in early January next year, journeying with our readers once again.

While our office will be relocating, the daily news commentary we launched on our website this year will continue throughout this period though. Our transformation of Sameway into a multi-platform Chinese media outlet will also continue next year. It is your support that convinces us that Sameway is not just a publication—it is a calling for a group of Christians to walk with the Chinese community. It is also the blessing God wants to bring to the community through us. We hope that in the coming year, Sameway will continue to stand firm as a Chinese publication committed to speaking truth.

Today, anyone making a request to U.S. President Trump must first praise his greatness and contributions—no different from the Cultural Revolution-style rhetoric we despise. Western politicians call this “political reality.” Russia, as an aggressor, shamelessly claims to “grant” conditions for peace to Ukraine, and other Western leaders must endure and compromise. Australians continue to face economic and living pressures, and immigrants are still scapegoated as the root of these problems, leaving people anxious. Sadly, last week Hong Kong suffered a once-in-a-century fire disaster, causing 151 deaths and the destruction of countless properties—a heartbreaking tragedy. Even more tragic is witnessing the indifference of Hong Kong officials responsible for the incident, and the fact that Hong Kong has now been fully absorbed into the Chinese model of governance—an authoritarian system dominated entirely by “national security” or the will of its leaders, where no one may question the truth of events or demand government accountability.

Yet, in the midst of such helplessness, I still believe that the God who rules over history is the same God who loves humanity—who gave His only Son Jesus to the world to redeem humankind.

Wishing all our readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! See you next year.

Mr. Raymond Chow, Publisher

Listen Now

Hope Amid Anti-Semitic Attacks in Australia

Examining Freedom of Speech in Hong Kong Through the Jimmy Lai Case

Victorian Farm Accused of Exploiting Migrant Workers

Middle-aged Couple Killed in Bondi Beach Shooting

Trump Says Gaza “International Stabilization Force” Already in Operation

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

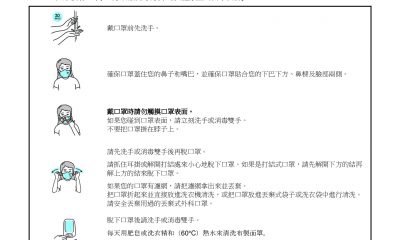

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單