Features

AI Competition Splits into Diverging Paths

Published

4 months agoon

The U.S. and U.N. Part Ways on AI Regulation

The United States and the United Nations are diverging in their approach to AI governance. Recently, at the U.N. General Assembly, the U.S. government explicitly rejected proposals to establish a global framework for artificial intelligence governance, highlighting a major disagreement with the international community on AI regulation. Michael Kratsios, the U.S. AI policy chief, emphasized at a U.N. Security Council meeting that the U.S. “completely rejects” any attempts by international organizations to exert “centralized control and global governance” over AI, insisting that the future of AI “lies not in bureaucratic management but in national independence and sovereignty.” Meanwhile, among the 193 U.N. member states—including China—the majority support establishing a framework for international cooperation. This reflects a growing global divide in technology governance, entering a new stage of fragmentation.

Rising Intensity of AI Competition

In recent years, China has rapidly emerged in the AI field, putting pressure on the traditional technological powerhouse, the U.S. China is leveraging its massive data resources to accelerate domestic innovation and promote algorithms abroad. Tech giants like Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei are driving cutting-edge innovations, developing advanced facial recognition systems, language-processing tools, and other technologies. At the recently held World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai, Chinese Premier Li Qiang proposed establishing a global AI cooperation organization to promote multilateral, open-source collaboration—signaling Beijing’s ambition to expand China’s influence in global geopolitics.

Recent data shows China leads the U.S. in AI patent applications by nearly tenfold, and China’s AI research output has surpassed the combined total of the U.S., the 27 EU countries, and the U.K. Facing this reality, the U.S. insists on maintaining its technological advantage through sovereign control, while China calls for strengthened international cooperation. The European Union, meanwhile, is pursuing a “third way” via its AI Act, formally released in July 2024, hailed as “the world’s first comprehensive AI law.” This multipolar governance model reflects a global AI landscape trending toward regionalization and fragmentation rather than unified international standards. Establishing an international AI organization is “one of the most critical issues of our time,” but achieving this goal requires direct negotiation and cooperation between the U.S. and China—a prospect that currently looks bleak.

In the West, concerns are growing that China’s dominance could shape global technology standards and governance, potentially exporting its ideology and weakening the influence of democratic nations in global tech governance. China has actively increased its participation in international standard-setting, particularly in developing countries, promoting AI systems like facial recognition with low cost and high efficiency. The most representative case is TikTok, which faced scrutiny over national security and data privacy while expanding abroad. The Trump administration restricted its use on government devices and demanded its sale to U.S. companies. With 170 million users in the U.S., over half the population, TikTok’s expansion prompted the White House to launch an “Action Plan” to enhance domestic technology and counter China’s influence. “Just as we won the space race, the U.S. and its allies must win this AI race,” the White House stated in the Action Plan.

Diverging Trends in 2025

This divide has become even clearer in 2025. According to Stanford HAI’s 2025 AI Index report, U.S. private AI investment reached $109.1 billion—almost 12 times China’s $9.3 billion—highlighting an innovation model dominated by Western capital markets. The U.S. produced 40 top-tier AI models, leading globally. However, China is rapidly closing the performance gap; a RAND report predicts that Chinese AI models will match U.S. capabilities by 2025. China focuses on “AI+” vertical applications, such as agricultural AI advisors and medical diagnostic systems.

The divergence stems from systemic differences: the West relies on market competition and open innovation, rejecting the U.N.’s global governance framework and emphasizing sovereign control to preserve its technological advantage. China, on the other hand, supports open-source models like DeepSeek through national funds (around ¥60 billion) and local government initiatives, emphasizing low-cost, scalable deployment. Discussions on X suggest that China’s “embodied AI” (robots) could dominate global value creation by 2030. The U.S. pursuit of AGI is disruptive, likened to an atomic bomb, whereas China’s application-driven approach is pragmatic—addressing export bans and achieving 70% domestic chip production. The result is a “dual-track” global AI ecosystem: Western high-end innovation and Chinese industrial empowerment, with China trailing only 6–12 months behind in model development.

Different Visions, Different Paths

Although competition between the U.S. and China in AI is intensifying, their development paths are increasingly distinct. The U.S. is investing hundreds of billions of dollars, consuming thousands of megawatts of energy, and racing to surpass China in the next AI evolutionary leap. Some view this leap as powerful enough to rival an atomic bomb in its impact on the global order. Since the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT nearly three years ago, Silicon Valley has poured vast resources into pursuing the “holy grail” of AI—Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) capable of rivaling or exceeding human thought.

China, by contrast, is running a different race. Amid growing concerns about an AI bubble, China has said little about AGI and is instead pushing its tech industry to “focus firmly on applied fields”—developing practical, low-cost tools that boost productivity and are easy to commercialize, countering Silicon Valley’s pursuit of superintelligent AI.

Currently, U.S. tech companies are developing pragmatic AI applications. For instance, Google connects its Pixel smartphones to the internet for real-time translation; U.S. consulting firms use AI agents to create presentations and summarize interviews; other companies improve drug development and food delivery. Unlike the largely laissez-faire approach in the U.S., China is actively supporting its vision. In January, China established a National AI Fund totaling ¥60.06 billion, focusing on startups, followed by local government and state-owned bank initiatives, along with city-level AI development plans under the “AI+” program.

While Chinese companies are releasing their best models openly, U.S. companies prefer to keep “shiny new products” proprietary. Meta, Google, and OpenAI compete heavily to secure talent, data centers, and energy. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) even recommended a “Manhattan Project”-style initiative to fund AGI development and ensure U.S. leadership. However, given uncertain returns on large-scale investment, the U.S. path may not be wiser. Ultimately, like the internet’s bubble and years of development, AI competition could take decades to determine winners.

This divergence affects not only technology but also the global economy, military balance, and societal change. AI is expected to contribute $15.7 trillion to global GDP by 2030. Western innovation drives high-value industries like cloud services and pharmaceuticals, but 95% of companies see no ROI, raising bubble concerns. China’s application model accelerates manufacturing transformation, reduces software costs, and affects U.S. software market valuation by $1 trillion. Supply chain fragmentation increases global costs by 2–3%, forcing developing countries to choose sides: U.S. security vs. China’s affordability.

The IMF warns that AI may widen the wealth gap, affecting 40% of jobs globally, benefiting Western white-collar workers while low- and medium-skill labor faces unemployment risks. The path leads to a multipolar economy, with China exporting AI systems to developing countries, weakening Western influence.

In military terms, AI divergence changes the global landscape. The U.S., through the AUKUS alliance, maintains air superiority and nuclear stability, but China’s hypersonic missiles and AI drone swarms threaten the Taiwan Strait. RAND simulations suggest U.S. missile stockpiles could be depleted in 72 hours, while Chinese AI electronic warfare disrupts radar systems. Chinese military AI investments escalate U.S.-China competition, and the U.S. Action Plan treats AI as a space-race-like challenge.

Global conflict is transforming. AI lowers attack costs, as seen in cyber and drone warfare in Ukraine. NATO faces Russia-China alliances; AI weaponization heightens South China Sea tensions, yet interdependence prevents full-scale war. GIS reports predict AI will reshape geopolitics by 2030, and the West must win the AI race to maintain advantage.

Societal change is also impacted. The West emphasizes transparency and ethics (e.g., EU AI Act), while China strengthens surveillance and efficiency. AI replaces routine work, with Western high-wage jobs benefiting from augmentative AI; China’s application model accelerates social control (e.g., police AI dispatch). Ethical divergence arises as the West worries about China exporting ideology, while China promotes digital collectivism. Paths lead to social polarization, a widening digital divide in developing countries, and fragmented AI ethics standards. Discussions on X suggest the AI “cold war” is forming new blocs, requiring policy buffers for employment transitions.

The Oligopoly Era Arrives

The AI industry’s competitive landscape is fundamentally changing. In the AI chatbot market, ChatGPT still holds a 60.6% share, Google Gemini 13.4%, Microsoft Copilot 14.1%, and other competitors under 7%. This concentration allows resource-rich tech giants to continually expand their lead. The global AI market is expected to grow from $391.7 billion in 2025 to $1.81 trillion by 2030, with a 35.9% CAGR—surpassing the cloud computing boom of the 2010s. Microsoft, IBM, AWS, Google, and NVIDIA collectively hold 42–48% of the market.

Notably, the AI industry is seeing a divergence in technological approaches. Google’s vertically integrated AI ecosystem—from TPU chips to application services—challenges NVIDIA’s dominance in AI chips. Microsoft recently announced it would use both Anthropic and OpenAI technologies in Office 365, ending its exclusive reliance on OpenAI—a “don’t put all eggs in one basket” strategy that reduces technical risk and improves user experience. This multi-vendor approach is emerging as a trend among major tech firms.

In response, OpenAI seeks independence, planning to mass-produce its own AI chips with Broadcom by 2026, reducing reliance on Microsoft Azure. OpenAI also launched a job platform challenging LinkedIn. Anthropic, through its Microsoft partnership, gains access to 430 million Office 365 users. Its Claude Sonnet 4 model already surpasses GPT-5 in some tasks, providing a differentiated advantage in enterprise markets.

In 2025, AI investment reached $364 billion, dominated by U.S. giants, though China is catching up. U.S. moves: Microsoft invests $80 billion in AI infrastructure and ends exclusive OpenAI reliance, adopting multi-vendor strategies (e.g., Anthropic); Google TPU integration challenges NVIDIA, raising market value 800%; OpenAI pursues independence and self-produced chips by 2026. Export controls maintain U.S. advantage, but Chinese open-source alternatives undercut profits.

China plans $98 billion in AI investments, including Huawei’s Ascend chip mass production, Baidu and Alibaba AI cloud deployment, and DeepSeek open-source models potentially disrupting Western profits. These efforts aim to circumvent U.S. localization bans, export low-cost hardware, and enhance domestic party-controlled applications.

Looking back, history repeats itself. The current AI competition resembles the cloud computing battles of the past—an oligopoly is forming. Few giants, with strong capital and computing power, will define the market, and the “winner-takes-all” principle will likely reappear. True winners often emerge over two to three generations; for example, Google is the third generation of search, Facebook the third of social networks. Who will ultimately dominate in brand building, independence, and market share remains uncertain.

Future Outlook

The diverging paths of the AI race suggest long-term uncertainty: Western innovation vs. Chinese applications. Globally, risks must be balanced. In 2025, a bubble may burst, but as with the internet, winners may only emerge after decades. Cooperation may be key; otherwise, fragmentation could exacerbate geopolitical tensions.

You may like

Raymond Chow

My New Challenge

Over the past few decades, I’ve written numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics. However, last October, I decided to write a book entirely different from anything I had done before, titled Solitary but Not Isolated. I chose to publish it through crowdfunding. Readers interested in supporting this book can visit the following webpage to learn more and help make it a reality.

I attended a rooftop school in Hong Kong for primary education (a unique feature of Hong Kong in the 1960s: temporary classrooms built on top of apartment blocks in resettlement areas to accommodate children who had moved into the district). Resources were extremely limited. In sixth grade, the school principal gave me and seven other students the opportunity to post our writings on the bulletin board every two weeks for the whole school to read. This was my first experience of writing for a public audience.

In secondary school at Queen’s College, the school published the annual magazine The Yellow Dragon, the earliest and longest-running secondary school annual in Hong Kong. My writings were never published there, though my photos occasionally appeared in reports of school activities. At university, I volunteered as editor for a scholarly publication by the Science Society called Exploration, but after two or three years it was discontinued as no one wished to continue it.

During university, I studied mathematics, which required little essay writing—mostly problem-solving. After entering the field of education, I wrote numerous articles on Hong Kong education that were published in newspaper columns. Later, through curriculum development and teacher training in Hong Kong, I had the rare opportunity to write and publish mathematics textbooks spanning from Grade 1 to Form 7—something unprecedented in Hong Kong.

After moving to Australia, I served as editor of the Christian publication Living Monthly, and eventually founded Sameway magazine, which continues today. From the first issue, I wrote the opening column Words of Sameway, and over 21 years, I have written a total of 745 pieces—a record of my life.

Yet writing Solitary but Not Isolated is something I never anticipated doing since I first learned about autism decades ago. Publishing this book is closely connected to my work with Sameway. I can only say this is a new challenge given by God, a chance to take Sameway to a new stage.

Those Who Love Solitude

Solitary but Not Isolated tells the story of a person with autism. Based on her experiences, the Happy Hands Organization has developed a bilingual training program to help autistic individuals transition from school to the workplace. Launched this year, the program aims to support others in similar circumstances.

Most people with autism do not actively seek social interactions. When they do engage with strangers, they may appear difficult to connect with or communicate with, often leading to social neglect or isolation. For parents and family, this creates a lifelong burden. Even those who complete secondary or tertiary education, despite having professional knowledge, often cannot fully utilize their abilities at work because of incomplete social understanding and lack of basic communication skills. Consequently, they are frequently relegated to jobs that do not match their abilities or are assigned work requiring minimal interaction.

Western society’s understanding of autism began with the lifestyle demands of modern life, emphasizing early social engagement and learning in school. Families, having fewer children, often pay close attention to each child’s development and have higher expectations. Over the decades, understanding of autism has evolved—from viewing it as a mental illness to recognizing it as a deviation from typical personality development. Yet how society should assist their growth remains uncertain.

Decades ago, Western focus was on “treating” autism. Research into genetic, environmental, or physical causes has made limited progress. Interventions to change solitary behaviors are also limited—for example, providing speech therapy in childhood or occupational therapy for daily living skills offers only partial support. While societal acceptance and support for autistic individuals have greatly increased, parents feel that more is needed when their children enter adult life and the workforce.

In short, those inclined toward solitude still face a gap in having equal opportunities to thrive socially and professionally.

Understanding Society and the World

Many autistic individuals focus intensely on specific interests, with little experience in social relationships or current events. As adults, this often leads others to perceive them as unaware of society, or even “odd.” In workplaces, where collaboration is essential, they may face exclusion. Many end up in solitary work with minimal social interaction.

Among Chinese communities, first- or second-generation immigrants with autism often face compounded challenges due to limited knowledge of society. Parents, unfamiliar with Australian systems, cannot fully guide their children, and these high-ability individuals rarely integrate with society, limiting opportunities to demonstrate their potential.

In 2024, ABC launched The Assembly, a TV interview program where host Leigh Sales trained 15 autistic individuals to conduct interviews and produce the show. Participants significantly increased their understanding of society and the world, and their communication and social skills improved greatly.

Last year, Sameway had the opportunity to train a bilingual autistic new immigrant, successfully helping her become a magazine editor. Meanwhile, the Happy Hands Organization developed a workplace adaptation program for bilingual, high-functioning autistic individuals. Through four to six months of training, this program offers these often-overlooked individuals a chance to adapt and develop in Australia.

Thus, Sameway is not only an information platform supporting immigrant communities but also provides a development space and opportunities for those with special needs. Readers interested can contact our magazine or the Happy Hands Organization for details.

The Loneliness of Immigrants

Many immigrants arrive in Australia as adults. They often lack opportunities to understand society deeply and, due to work and life commitments, rarely have the time to engage fully with their new environment or develop close relationships with Australians. Consequently, most live within Chinese communities with similar backgrounds. Passive personalities or limited social skills often lead to intense feelings of loneliness.

Leaving their original home and social networks creates a sense of marginalization similar to that experienced by some autistic individuals. Many immigrants are willing to understand and engage with their new society but face personal limitations and a lack of proactive governmental support, leaving them unable to integrate fully into Australian life.

Chinese immigrants, in particular, may rely heavily on long-term Chinese social media and information platforms, further isolating them from the broader society. This social isolation significantly affects their participation and engagement in Australian life.

The goal of Sameway is to assist immigrants in integrating into Australia, fostering participation and engagement in society. We hope that with continued support, we can go further and achieve more.

During the Christmas and New Year period, “Sameway” relocated though only to a spot less than 100 meters across from their original office. It was a tiring task, but we have finally settled in, allowing us to take a longer break during the holiday.

However, the world still undergoes significant changes. The President of Venezuela has been forcibly taken to New York for trial, while the new leader of Venezuela is willing to govern in line with U.S. interests. The longstanding alliance between Europe and the U.S. has become history in light of the U.S. attempt to purchase Greenland. The “Board of Peace” established by Trump requests that nations place the keeping of global peace in his personal hands, but attendees at the invitation include authoritarian dictators who have initiated wars multiple times. The generation that has grown up advocating for global integration, respect for human rights, and peaceful coexistence is now at a lost and confused. Will the world revert to a chaotic state governed by the law of the jungle, where strong countries dominate weaker ones, or can humanity choose to move forward in civilization by learning mistakes from history? We truly have no sure answer.

However, it is a time where the rise of Trump and the increasing power of global far-right political forces, coupled with the internet and social media replacing traditional media as the main source of information for many people. This has led to a society overwhelmed with information and challenges in distinguishing truth from falsehood, which is equally as frightening as an era where information is blocked, preventing access to necessary knowledge.

In Australia, as a multicultural country, immigrants face significant difficulties in obtaining lifestyle information through mainstream media. I believe that to build Australia as a harmonious and cohesive society, the government must invest substantial resources to assist immigrant communities to establish high-quality and credible multicultural media, and to accelerate the integration of first-generation immigrants into society, allowing them to become a driving force in social development.

In the past year, we have strengthened the current affairs information provided on our website. In the coming year, we will focus on enhancing our information services for the Chinese community through our broadcasts and magazine publications. I hope you can support us in achieving the goal of promoting the development of the Chinese immigrant community.

Starting this year, in line with the REJOICE’s initiative for bilingual new immigrants with autism, I will be writing a brand-new column to explore this topic with the community as they navigate With the NDIS program. I hope this innovative program by the REJOICE will receive your support for promotion and development within the community.

Additionally, after three years of training aimed at encouraging seniors to use social platforms to expand their community engagement, we will take a further step this year by launching training courses to assist seniors in using artificial intelligence. Our goal is to help Chinese seniors in Australia stay up-to-date and enjoy a higher quality of life brought about by AI.

In the new year, let us work together to build a stronger local Chinese community.

Since January 20, 2025, when Trump assumed the U.S. presidency once again, domestic issues in America have been frequent and complex, but the world cannot deny that his foreign policy has reshaped the global political landscape, ushering in a new era.

Over the past year, Trump has been extremely proactive in foreign affairs—from Greenland to Venezuela—demonstrating relentless ambition to expand U.S. influence abroad, even amid controversy and the risk of destabilizing other nations.

Prelude to 2025

Let’s briefly review Trump’s major foreign policy actions in 2025.

First, his involvement in the Gaza Strip cannot be overlooked. In February 2025, he publicly stated that the U.S. would play a more active, even leading, role in the region, supporting Israel’s security needs, including strengthening border defense and intelligence sharing. He also attempted to broker ceasefire talks in the U.S.’s name, coordinating Egypt, Qatar, and other countries as intermediaries. By October, Trump personally attended a multilateral meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, pushing for a ceasefire agreement and reconstruction framework between Israel and Hamas.

While opinions on his approach were divided, with some critics arguing that direct intervention could heighten regional tensions, Trump nonetheless reaffirmed America’s influence and presence in Middle Eastern affairs.

Early in 2025, the Trump administration reviewed all foreign aid and temporarily halted military assistance to Ukraine, using it as leverage to push forward negotiations. By mid-March, following U.S.–Ukraine consultations, military and security support resumed, including air defense systems, drone technology, and financial assistance. The U.S. also advocated international sanctions against Russia, such as high-tech export restrictions and asset freezes. These actions demonstrated Trump’s support for strategic allies and further solidified U.S. influence in Europe.

While these events may seem unrelated, they set the stage for early 2026’s diplomatic developments.

The Venezuela Raid

Trump’s most notable action in January 2026 was the sudden capture (or abduction) of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife.

In fact, as early as December 1, 2025, Trump had called Maduro, demanding he step down. When Maduro refused, Trump publicly ramped up pressure in mid-to-late December, applying economic and military pressure—including blockades, intercepting suspicious ships, and bolstering military deployments—to isolate the Maduro government. He even hinted that further U.S. action might follow if Maduro continued to resist, signaling a preemptive warning.

The result: U.S. forces launched a large-scale operation codenamed “Absolute Determination”, storming Caracas, capturing Maduro and his wife, and transporting them to New York for trial. The justification cited Maduro and his inner circle’s involvement in drug trafficking and terrorism, including conspiracies to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. At the same time, Maduro’s government had close ties with China and Russia, who provided military and economic support, posing a threat to U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The operation was also seen as a move to block rival powers from gaining leverage in Venezuela. More importantly, given Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, Trump clearly aimed to reassert U.S. dominance in the hemisphere and secure economic benefits. For many Americans, the raid showcased U.S. military might, boosting Trump’s prestige and approval. True to form, Trump paid little attention to criticism, focusing instead on praise, and was visibly self-satisfied.

International reactions were strong. China and Russia immediately condemned the U.S. action, calling it a severe violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and international law. Iran and other nations with tense U.S. relations also criticized the operation as unilateralism under the guise of anti-drug and anti-terrorism efforts, destabilizing the region.

European responses were mixed. Some EU countries long critical of Maduro still expressed reservations about the U.S. bypassing international authorization for direct military action, emphasizing that even dealing with authoritarian regimes should follow international mechanisms. This tension revealed the strain Trump’s style places on traditional allies.

In Latin America, reactions were split: anti-Maduro governments and Venezuelan opposition privately supported the move as a chance to break political deadlock, while others feared overt U.S. military intervention might revive Cold War-era “Monroe Doctrine” fears, worsening regional security.

Currently, former Vice President Rodríguez serves as interim president of Venezuela, cooperating with the U.S. while maintaining loyalty to the domestic ruling class, keeping the country relatively stable. For Trump, the goal of preventing other powers from gaining influence in the Americas and securing economic gains was achieved. Many Americans saw the raid as a demonstration of military strength, reinforcing Trump’s image as a decisive leader.

Trump’s Greenland Gambit

Since 2025, Trump has repeatedly brought Greenland into the spotlight, making it one of the most challenging and controversial topics of his second term.

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is under Danish sovereignty but enjoys local autonomy. Its location between North America and Europe along the Arctic shipping route has made it strategically valuable. Previously overlooked due to extreme cold, climate change and melting ice have expanded Arctic navigation, increasing Greenland’s military and technological importance. The island also contains vast deposits of rare earth and critical minerals, essential for modern technology and defense systems.

Trump’s assertive approach clearly aimed to maximize U.S. influence over Greenland. In 2025, he publicly expressed interest in buying Greenland and urged negotiations to secure it, even hinting at military options. This escalated tensions with Denmark and Europe.

European reactions were unanimous: Greenlandic leaders stated the island is “not for sale”, and massive protests erupted in Greenland and Denmark. The UK prime minister warned Trump that high tariffs or aggression would be a grave mistake, while EU countries—including Denmark, France, Germany, and the UK—supported Danish sovereignty. Even European far-right parties, traditionally aligned with Trump, criticized his Greenland strategy as overt aggression, causing internal rifts.

At the 2026 Davos World Economic Forum, Trump and NATO Secretary-General Rutte reached a “preliminary framework” focusing on Arctic security cooperation rather than territorial control. Trump framed it as safeguarding U.S. military bases and economic interests, while Denmark retained final authority. However, Greenland’s government stressed it was not fully involved in negotiations, highlighting an ongoing tension. Analysts debate whether this is a tactical retreat or pragmatic compromise.

Even with the temporary easing of tensions, U.S.–Europe trust has been strained, showing how far-reaching Trump’s assertive diplomacy has become.

Iran Unrest and U.S. Pressure

From late December 2025, Iran experienced nationwide protests, initially triggered by economic collapse, currency devaluation, and skyrocketing living costs, evolving into broad dissatisfaction with the regime. The government’s harsh crackdown led to casualties and arrests on a scale unseen since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The U.S., which maintains heavy sanctions against Iran citing terrorism sponsorship and nuclear/military threats, seized this moment to intervene. Trump publicly announced deploying a fleet—including aircraft carriers and missile destroyers—to the Persian Gulf to deter further escalation. He emphasized a preference for avoiding force but warned of potential military action if the regime continued violent repression.

Trump also communicated with Iranian protesters via public statements and social media, encouraging demonstrations and denouncing government violence. He canceled all official diplomatic talks until Tehran ceased the crackdown. While some protesters hoped for U.S. support, the absence of direct action led to frustration and feelings of abandonment.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard leaders warned that any U.S. strike would be considered a full-scale war. Protests and anti-U.S. imagery reflected strong resistance. Intelligence reports indicating a temporary halt in state violence led Trump to consider pausing military actions while closely monitoring the situation, balancing threats with cautious observation.

Trump’s strategy combined military presence and public warnings to pressure Tehran, deter large-scale killings, and strengthen U.S. influence in the Middle East. Yet this high-risk approach also raised the possibility of miscalculations, where tensions could escalate unintentionally, making the U.S. a target for criticism and resistance.

The “Board of Peace”

Traditionally, the U.S. has been seen as the global big brother. But with China’s growing influence and global economic support programs, U.S. presidents often feel impatient with Beijing’s increasing UN sway. Trump, ambitious and assertive, sought to take matters further.

At the 2026 Davos Forum, he launched the “Board of Peace”, initially proposed to address Gaza peace but now expanded to serve as a broader global conflict mediation mechanism. The initiative leverages U.S. influence to create an alternative diplomatic platform and invites multiple countries to participate.

However, critics question whether it is more for show than genuine peacekeeping. The EU’s concern lies less with the stated goals and more with the lack of clarity: the legal status, decision-making process, funding, and international law accountability remain unspecified. Unlike multilateral bodies like the UN or OSCE, this U.S.-backed, president-driven mechanism risks becoming a coercive tool rather than a genuine mediator.

The EU fears it could undermine Europe’s long-standing role in Middle East diplomacy, forcing it from rule-maker to follower. China was excluded, reflecting Trump’s view of Beijing as a competitor, not a partner. The Board aims to present participation as a political statement, effectively creating a U.S.-led bloc in global conflict mediation.

For Australia, the Board is a hot potato. Prime Minister Albanese received an invitation but has not confirmed participation. Several NATO and EU countries have declined, while Canada was disinvited over disagreements on China policy. Thirty-plus leaders who accepted include war actors like Putin and Israel’s Netanyahu. How they could effectively promote peace remains questionable, and handling the invitation diplomatically will test Albanese’s political skill.

Trump’s Diplomatic Logic

Across Gaza, Ukraine, Venezuela, Greenland, Iran, and the Board of Peace, Trump’s strategy is consistent: proactive engagement, pressure, disruption of norms, and forcing allies and adversaries to recalculate. He eschews slow multilateral negotiations in favor of military, economic, and media leverage, coupled with highly personalized decision-making, shifting power quickly at the negotiating table.

To Trump, diplomacy is a continuous game of strategy, not merely maintaining order. He pushes situations to the edge, then retreats strategically to gain advantage. While controversial and eroding trust among allies, it successfully recenters U.S. influence.

Crucially, Trump applies pressure not only to adversaries but to allies, forcing them to demonstrate loyalty or strategic value. This increases U.S. bargaining leverage but consumes trust capital, making international relations more transactional and short-term, and setting the stage for future friction.

Costs and Risks of Assertive Diplomacy

Reliance on pressure and uncertainty may yield short-term results but risks long-term instability. Highly personalized, low-institutional approaches erode trust in rules, procedures, and multilateral cooperation. Misjudgments are more likely in opaque, high-stakes situations. Allies and adversaries may misread threats, escalating conflict even without provocation.

Trump is reshaping U.S. diplomacy from guardian of order to rewriter of order, providing tactical flexibility but weakening institutional credibility. Whether the U.S. can balance assertive pressure with sustained trust will determine its long-term global leadership.

Ultimately, Trump’s strategy may open new strategic space for the U.S. or provoke deeper backlash and confrontation. One thing is certain: the international stage in 2026 is no longer the old world, and Trump is the key variable driving this structural transformation.

Listen Now

Pro-Trump Brazilian Influencer Arrested by U.S. ICE

German Chancellor Merz Discusses “Shared Nuclear Umbrella” with European Allies

Australian Government Unveils Blueprint for Autism and Developmental Delay Programs

One Nation’s “Spot the Westerner” Video Condemned

Littleproud retains leadership, Sussan Ley’s position uncertain

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

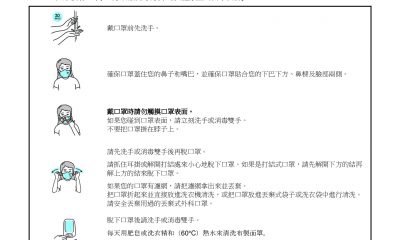

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized6 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單