Features

I’m an Indigenous Chinese Australian!

Published

12 months agoon

I’m an Indigenous Chinese Australian! (Part 1)

This year marks my 30th year living in Australia. Through writing, volunteering, and social dancing, I’ve made countless friends from all walks of life: Australians, Europeans, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Filipinos, Malaysians, North Americans, Indians, New Zealanders, and even South Africans. I’ve had great teachers, good friends, bad influences too, all from across the globe. Life has been vibrant, interesting, and long. However, I regret that not one of my friends is an Indigenous Australian, and I know very little about Indigenous communities, their culture, and traditions. This regret often leaves me feeling empty, as though something is missing. Over the years, I’ve only met two Indigenous women: one was a friend’s girlfriend whose grandmother was Indigenous, but she was fair-skinned with delicate features, and there was no outward sign of her Indigenous heritage. The second was Professor Marcia Langton AO, a professor at the University of Melbourne. I first saw her in 2008 when I interviewed the famous Australian painter Zhou Xiaoping (see my article “In Search of Dreams in the Indigenous Dreaming World” in Issue 85 of Sameway). I met her again at a Lunar New Year banquet at Zhou’s house the same year. In 2012, at the screening of a film about Zhou Xiaoping (see my article “Ink and Ochre” in Issue 314 of Sameway), I met Professor Langton again, but both times, I missed the chance to speak with her. In recent years, this sense of loss and regret has grown stronger, eventually prompting me to begin a quest to learn more about the First Nations of Australia.

Indigenous Australians, a term that refers collectively to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, are the descendants of the original inhabitants of Australia before European colonization. The term “Indigenous Australians” is a broad one, encompassing many different groups with significant distinctions between them. They may not share close connections or common origins, with each community having its own unique culture, customs, and language. It’s estimated that when Europeans first arrived, there were around 250 Indigenous languages. Now, only about 120 to 145 languages remain, most of which are endangered, with only 13 considered secure. Most modern Indigenous Australians speak English that is influenced by Indigenous vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammatical structures, a form known as Aboriginal English. Estimates of the population at the time of European settlement vary, with some suggesting between 318,000 and 1,000,000 people. They mainly lived in the southeast, which mirrors today’s population distribution. The current Indigenous population is 798,365, with 73% identifying as Christians, 24% having no religion, and 1% adhering to traditional Indigenous beliefs. There is no academic consensus on the relationship between the first inhabitants of the Australian continent and modern Indigenous Australians. However, most scholars agree that the earliest human remains found in Australia date back between 64,000 and 75,000 years, making them descendants of the earliest groups to leave Africa for Asia. Since 1995, the Aboriginal flag—red and black with a yellow sun—and the Torres Strait Islander flag—blue and green with a headdress symbol—have been recognized as official national flags in Australia. (Note 1)

Last week, through a friend’s introduction, I had the opportunity to learn more about Indigenous culture via several Australian television programs. The stories I’ll share here are based on ABC broadcasts (May 2020).

The Aboriginal Chinese Doll

I’m Brenda, an Elder of the Bidjara-Wakka Wakka nations. At 68 years old, I’ve always been curious about Chinese culture. Why? Because my grandmother used to call me “Chinese Doll.” I found the answer when I was four years old. It was the first time I discovered that I had Chinese ancestry. One day, while playing with other kids, I asked my grandmother, “Why do you call me Chinese Doll?” She told us that we were descendants of Chinese people. We continued asking, and she explained that my great-great-grandfather was Chinese. I grew up in Gayndah, a small town about 350 kilometres north of Brisbane, where my mother’s family are the traditional custodians of Wakka Wakka Country. Apart from that conversation with my grandmother, Lucky Law, and the taste of the fried noodles my mother May used to make, I knew very little about my Chinese roots, and even less about my mysterious Chinese great-great-grandfather. I couldn’t learn much from Lucky, as marriages like hers were seldom discussed back then. I only asked that day out of curiosity, but that curiosity has stayed with me, leaving a big gap in my life.

The First Generation of Chinese Shepherds

I’ve worked as a part-time teacher at a public school in Queensland for nearly a decade. A few years ago, I started exploring my family history in my spare time. My family tree reveals that one branch can be traced back to my great-great-grandfather John Law. He arrived in Australia around 1842 as a shepherd from Xiamen. He worked in the Gayndah region, where he apparently met my great-great-grandmother, and they married. It turns out I’m about one-fourteenth Chinese. In the 1840s, around 3,000 Chinese labourers, mainly men and boys, were transported from Xiamen to Australia to work as shepherds, spreading across modern-day Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland. Dr. Maxine Darnell has been tracing the history of these shepherds, who were brought under five-year contracts and worked under harsh conditions as part of the first organized wave of Chinese labour to Australia. They helped meet the labour shortage after convict transportation to Australia ceased in the 1840s, before the influx of Chinese gold seekers in the 1850s and 1860s. As contract labourers, they were bound to their employers, unable to freely leave for the goldfields like many free workers. While little is known about the reasons behind their migration, it coincided with China’s recovery from the Opium War, when the lure of a better life must have been appealing. The story of labourers seeking a better life is a timeless one.

From Hostility to Intermarriage

The interaction between Chinese and Indigenous Australians dates back at least 150 years, though much of this history remains undocumented. Dr. Sandi Robb has been researching the relationships and marriage patterns between Chinese men and Indigenous women in Queensland. According to Dr. Robb, the early relationship between the two communities was fraught with “hostility and fear.” From the Indigenous perspective, the Chinese were unfamiliar people, different in appearance and dress, trespassing on their land without permission, thereby violating Indigenous law. However, over time, Indigenous marriage customs began to break down, and instances of intermarriage with other ethnic groups appeared. By 1890, Indigenous women were often left with no choice but to marry outside their communities due to the loss of traditional marriage partners, often due to violence. Both the Indigenous and Chinese were marginalized and looked down upon by white settlers. John Law was one of the few Chinese shepherds who married an Indigenous woman. Their daughter, Kate Law, married Chinese shepherd James Coy in 1877, and they had 11 children, including my grandmother, Lucky Law.

Indigenous people and Chinese workers formed friendships and connections that bridged their worlds. Both groups faced discrimination, and like today, that prejudice still affects both Indigenous Australians and Chinese. I believe that both groups learned much from each other, including cultural practices and agricultural knowledge related to land and cattle. In Gayndah, there were also orchards and citrus groves. In 2019, the Queensland government recognized the contributions of Chinese shepherds in irrigation and crop production in the Darling Downs region.

The Quest for Chinese Roots

My journey to trace my family history would have been much more difficult without the help of a Chinese friend. In 2018, I met a young Chinese man named Xianyang Tang on Facebook, and we quickly became friends. Over the past two years, with his help, I’ve uncovered many unknown aspects of my family history. Xianyang knew how deeply I wanted to find at least one relative and learn more about my great-great-grandfather’s origins, so he helped connect me with the Luo clan in Xiamen and local Chinese people. However, the search hit a roadblock when we couldn’t confirm which branch of the Luo family my ancestor belonged to, possibly due to the destruction of Luo family records during the Cultural Revolution. Xianyang was moved by my determination to uncover my roots and volunteered to help me. He visited me during my illness and even bought shoes and hats for my children. To me, he’s like family. He believes that my ancestors came from the Luo clan in Xiamen, but the search continues.

I’ve always felt proud of my identity. I have a large family descended from John Law, and none of us has ever denied our Chinese heritage. My dream is to visit China, especially Xiamen, to see it for myself and imagine the footsteps of my great-great-grandfather. While I know a lot about Indigenous culture, I’m part of two cultures, and I’ve decided to explore that other half.

Since the 19th century, Chinese and Indigenous Australians have walked side by side with untold stories!

Hi, I am a Chinese Aborigine in Australia! (II)

Recently, I had the pleasure of meeting CityMag and Ngarrindjeri (multidisciplinary) artist Damien Shen on the program to talk about his upbringing and what it means to be Aboriginal and Chinese.

Yellah Fellah: The Yellow-Skinned Family Man

Yellah Fellah is a colloquialism, an Australian term for yellow people. I, Damien Shen, am what Australians call Yellah Fellah, the yellow-skinned guy. However, my Aboriginal and Chinese backgrounds are deeply connected, and my Chinese heritage played an important role in my childhood. I am not sure where I would be today without the benefit of my Chinese heritage. My father was born in Hong Kong but was sent to boarding school in Adelaide. My grandparents thought the Communists would soon take over Hong Kong, so my father’s sister was sent elsewhere and then he was sent to Australia. I was born in Adelaide and my grandparents, who lived next door, were important people in my childhood. I think as I got older I appreciated more the Chinese side of things, that they were able to build up such structures, things that happened in my father’s life and so on. My Chinese grandmother felt it was her duty to keep order in the home – breakfast would be brought out at a certain time and dinner was always at 6pm. Grandparents provide a safe structure for children to live in. Although proud of my Chinese heritage, I admit that growing up in Australia with undeniable racism against Asians was challenging. I don’t speak Chinese because when my father came here, there was a lot of racism, so he was like, “No, you’re speaking English.” He wouldn’t encourage us to speak Chinese. At home he spoke Cantonese, and my grandparents spoke Cantonese, Mandarin and Shanghainese, and then they would go around the table and speak English to us. I recall my first job at a Chinese restaurant, where it was harder to fit in because I didn’t know the Chinese language. I was perceived as someone with long hair who didn’t speak Chinese, which was almost a bit of a novelty to the Chinese. I was there, but never really connected with the Chinese.

My mother’s Ngarrindjeri ethnicity, my Aboriginal heritage, was also crucial to my childhood. Growing up, I always knew I was part of an Aboriginal community and had many Aboriginal cousins with whom I spent a lot of time. One of those family members was Uncle Moogy. Moogy, who everybody knows – he’s my mom’s brother, so he’s actually my real uncle, and I grew up with him. There were always a lot of children in his house and we always spent the night there, so it was always very fun and memorable and I’m still very close to him. Although I now appreciate my Aboriginal and Chinese heritage, there are still struggles, especially at a young age. When I was in about 10th grade, I encountered a lot of racism in terms of being Asian or Aboriginal – basically, “they” had two ways of dealing with me. Then I changed schools and things changed immediately because I went to a very multicultural school. Suddenly, I didn’t have that pressure to ‘stand out’. It wasn’t until I was older that I started researching my Aboriginal heritage. As you get older, you start to think more about genealogy, history and things like that. …… It’s so fascinating when you look at what it means to be an Aboriginal person with family ties from a genealogical perspective. Anyone you meet, you call each other by name, but you’re not quite sure how far apart we are – are we really cousins? Then, on the other hand, you see what being Aboriginal means politically, historically, what happened to the Ngarrindjeri people, so part of my work deals with that. I looked back at my own life in two different contexts and felt blessed. I was lucky to be able to experience it through two lenses: dual identity, or dual background – it’s an interesting thing. As I’ve experienced, you don’t always fit into the Aboriginal community environment, especially when I was young, I felt that. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten to know more Asian Aboriginal people, and we all look the same.

Yellah Fellah for OzAsia explores storytelling through an Indigenous Asian lens.

Yellah Fellah for OzAsia, an art exhibition curated by Catherine Croll, is on display at the Adelaide Festival Centre in 2023. This fascinating and inspiring exhibition featured the work of four different artists with Asian and Aboriginal traditions. I am exhibiting my own work alongside Gary Lee, Caroline Oakley and Jason Wing to show our personal interpretations of our backgrounds through the art form, which is essentially a gathering of many artists with Asian and Aboriginal traditions. For me, it’s Chinese and Aboriginal, and I think the artists will be proud of this mix of hybrids. I don’t speak for any other artist. …… Having a Chinese and Aboriginal heritage is something I’ve always been extremely proud of. You don’t see as much Aboriginal Chinese in South Australia as you do in the north of Darwin, there’s more of a mix of Asian Aboriginal cultures, but I’ve felt it’s quite unique here for a while now, so that’s cool. Curator Catherine says Asian-Australian relations began centuries before the European colonization of Australia, when Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory began to build a sea cucumber trading network with Malaysia and then on to China. I created a pewter skull fragment at an anatomy lab in Virginia entitled Life Behind the Pen, which is a history of the theft of human remains – many of the Ngarrindjeri people’s remains were stolen and shipped overseas. Uncle Moogy had a huge influence on a large group of Aboriginal leaders who travelled abroad to find these remains and repatriate them to Australia. My work here embodies that idea, and the photographs that Uncle Moogy and I have deliberately taken in this ethnographic way are like a real classic style of documenting things at a certain point in time, kind of like a drama of that history. The artwork called “Portraits” was a personal favorite of City Magazine, black and white portraits of my grandparents, sisters and uncles. Then I was inspired to organize a painting workshop with an American, and I thought, I don’t mind documenting all the stories around my mom. And then on the other hand, I’m going to document my Chinese grandparents and my sister as part of this series, linking the Chinese and Australian Aboriginal elements.

Chinese Aboriginal Women Writers

Not long ago, I saw some exciting news on SBS Chinese TV: Ms. Alexis Wright, a Chinese Aboriginal woman, won $60,000 and the Stella Prize for non-binary writers this year for her novel Praiseworthy, which beat out 227 entries. 2018 is the year that she writes about Aboriginal chiefs. In 2018, her collective memoir of Aboriginal chiefs, Tracker, also won the Stella Prize, making her the first author to win the award twice. She also won the Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s highest literary prize, for Carpentaria. Described by the New York Times as “the most ambitious and accomplished Australian novel of the century”, the 700-page book has been described as a great book in many ways, telling the story of the John Howard. Howard government’s 2007 military intervention in a Northern Territory community, the story of a small town whose inhabitants have been struck by a haze, and the story of the Aboriginal people who have been forced to live with the government’s military intervention in their community. This is a story of Aboriginal ancestry and ecological disaster. The characters’ reactions to the situation are allegorical, ranging from the comic to the tragic: one man devises a plan to replace Qantas with five million donkeys across Australia, another dreams of being white and powerful, and a third, apparently named Aboriginal Sovereignty, becomes suicidal. The judges were unanimous in stating that readers would be inspired by the aesthetic and technical qualities of Worthy of Praise and struck by Wright’s staccato rhythms of satirical politics, and that the award was rightfully given to Wright.

Challenge Yourself

Wright made a commitment long ago to challenge herself in whatever she writes, and her ambition has grown over the years. She began writing this novel about ten years ago, much of it during her tenure as Boisbouvier Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Melbourne. The process required Wright to pause and restart many times as she tried to evoke the slow pulse of central and northern Australia, to capture the scale of the period and the immense difficulties of the time, to challenge the reader’s indifference and to try to replace it with a deeper understanding. In an interview with the Australian Associated Press AAP, Wright pointed out that there is no harm in exercising the brain through the reading of good books. People are happy to go to the gym for a good physical workout, and there is no harm in a good workout for the mind.

Chinese Great-Grandfather & Native Great-Grandmother

“I come from one of the greatest storytelling worlds,” Wright said at the Stella Prize ceremony, “We are a culture of storytelling. Some of the most important, richest and longest-running epical law stories belong to the indigenous cultures of this land.” Wright, 73, is of Chinese descent. His great-grandfather came from Kaiping, Guangdong Province, to make a living in the Gulf of Carpentaria, a remote region in northern Australia, following the gold rush of the 19th century, and later married his Waanyi Aboriginal great-grandmother. Wright was invited to Shanghai for Australian Writers’ Week in 2018 and revealed in a media interview, “My great-grandfather was Chinese, but I don’t know him or the exact location of his hometown. I think it was somewhere in Kaiping, Guangdong. In the 19th century in Kaiping, a lot of Chinese people left their hometowns and went to the United States, Canada and other places to look for gold. Great-grandfather brought a lot of knowledge about China to the Gulf of Carpentaria, and he taught community members about irrigation and farming and growing vegetables.” She made a trip to Guangdong in 2017 to search for her roots, but unfortunately was unable to find any trace of her great-grandfather, after all, it was too long ago. Her books are available in Chinese translation, including the Franklin Award-winning Carpentaria and the full-length novel The Swan Book.

Bridging the Gaps in Australian History

During an unusual trip to the Northern Territory in 1988, renowned Australian painter Zhou Xiaoping was rescued by three Aboriginal teenagers when he was lost on a vast sandbar, which initiated his intense interest in Aboriginal culture and profoundly influenced his subsequent works, making Aboriginal people the only protagonists of his paintings. Through understanding, respect, and sincerity, he broke the barrier and formed decades of friendship with the Aborigines, making friends with Jimmy Chi, a Chinese Aboriginal musician, and Peter Yu, a professor. (See my articles “Seeking Dreams in the Aboriginal Dream World”, “Ink and Ochre”, and “Exploring Aboriginal History of Chinese Descent” in the 85th, 314th, and 665th issues of The Wayfarer) In 2022 Mr. Zhou initiated a project, Exploring Forgotten History, which is a project to explore the history of Aborigines in China, and to explore the history of the Chinese Aborigines in the world of Aborigines in the world of Chinese culture and culture. In 2022, Mr. Zhou initiated a project entitled “Exploring Forgotten Histories” to study Aboriginal people of Chinese ancestry, the significance of which is to fill in the gaps in Australian history. In the study of Chinese history, there is a large amount of information on the Chinese gold rush, but the relationship between the Chinese and the Aboriginal people is seldom covered. Why is it that in the early gold rushes in Bendigo and Ballarat, Victoria, there were not many intermarriages between the Chinese and Aboriginal people, and why are there not many Aboriginal descendants left behind? This is an important part of our history that we are gradually forgetting. Mr. Zhou’s research and the emergence of Aunty Brenda Kanofski, Damien Shen, Alexis Wright, Jimmy Chi, Peter Yu and other Aboriginal people of Chinese ancestry are like a jigsaw puzzle, putting together a picture of the past that has rarely been talked about or forgotten, showing the rich and complex interactions between the descendants of two of the oldest civilizations in the world, the Bendigo and the Ballarat. It shows the rich and complex interactions between the descendants of two of the world’s oldest civilizations. Will all this contribute to the integration of Australia’s diverse peoples and the harmony of its cultures? We look forward to it!

Knowing, Understanding and Respecting Aboriginal Culture

As we enter the month of May, the message of “Reconciliation” has appeared frequently in the media. What is reconciliation? Why Reconciliation? How to reconcile?

According to the Oxford Dictionary, “Reconciliation” means to end a disagreement or conflict with someone and start a good relationship again. But in Australia the concept of reconciliation is not so simple. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians have always tried to reconcile their differences, and Reconciliation is of great importance and significance to the nation. National Sorry Day is celebrated on 26 May each year, followed by National Reconciliation Week from 27 May to 3 June. The start and end dates of the week are historically significant, and are designed to promote the reconciliation of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The week begins and ends with historically significant dates to promote reconciliation between Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal Australians. This year, the theme for National Reconciliation Week 2024 is ‘Now More Than Ever’, and now more than ever, we have the opportunity to think about how we can use this knowledge and these connections to create a better Australia. Let’s learn and reflect on our shared history, culture and achievements with the Aboriginal community through the presentations of SBS Chinese Aboriginal reporter Mr. Ryan Liddle and CEO of Reconciliation Australia (National Reconciliation Association Chief Executive Officer) Aboriginal Ms. Karen Mundine.

History of Reconciliation Week

Reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians can be traced back to the arrival of the Englishman James Cook in 1770; it is also thought to have begun with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and was formalized with the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Finding that too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were incarcerated and often detained, the commission submitted a report with more than 300 recommendations to address the crisis. While many of the recommendations have yet to be adopted, the last recommendation in the report, No. 339, stands out: initiate a formal reconciliation process. The Aboriginal Reconciliation Commission Bill was passed by Parliament with the support of both the government and opposition parties, and in 2001 the Commission was replaced by a new organization, Reconciliation Australia, which is still in operation today. Before the handover, two key events marked new beginnings, signalling a promising new era. Karen Mundine said: “We’ve seen governors, territory leaders, federal governors and prime ministers from all states come together to make a commitment to the spirit of reconciliation, and what we really need to do is to build positive relationships, to make sure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are seen as Australians, the first Australians, and that we are the oldest continuous culture in the world, and that we celebrate this uniqueness and we are proud of it. We celebrate this uniqueness and are proud of it. Ryan Liddle said: “On this day, this week, Reconciliation Australia was born, this was our starting point, nearly a quarter of a million Australians marched on the Sydney Harbour Bridge in support of reconciliation on a freezing cold and windy morning, and it was a truly transformative moment, a moment of unprecedented support from a wide range of communities to usher in a millennium of new opportunities to join together in a common journey to improve race relations. Since then we have had many successes, launching thousands of Reconciliation Action Plans, raising awareness of Aboriginal issues amongst the general public and generally improving the overall image and status of Aboriginal people in Australia.”

The most significant moment was the government’s action on February 13, 2008, when then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said in Parliament, “We apologize for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have caused deep grief, pain and loss to our fellow Australians. Prime Minister Rudd apologized to the nation, and as the world watched, there were cries of relief, tears of joy and sadness, and many Australians took to the streets holding up signs that read: I’m Proud to say Sorry! This day is known as National Sorry Day in Australian history. The next big push for reconciliation came about a decade later, in late May 2017, when a citizen-led Aboriginal National Constitutional Conference, including Aboriginal leaders, academics, social activists and others from across the country, worked hard to reach a rare consensus to constitutionally authorize the creation of an Aboriginal voice in Parliament, a treaty, and the establishment of a Truth Commission. For Aboriginal people, this sovereignty is a spiritual concept that has never been ceded or extinguished, and exists alongside the authority of all levels of government.20 In October 2023, a referendum to affirm the Aboriginal and Tortugas Channel Islander National Congress failed, and Australians voted down the establishment of an Aboriginal and Tortugas Channel Islander National Congressional Voice.

Respect for Aboriginal Etiquette

Why is it important to show respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ceremonies? Because an understanding of these ceremonies can affect our behaviour and our relationships with Aboriginal people. Exploring the richness of Aboriginal traditions, getting Aboriginal etiquette right and learning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customs are fundamental to respecting Australia’s heritage and the land we all live on. Mr. Thomas Mayo, advocate and writer for the Kaurareg, Kalkalgal & Erubamle peoples, introduced the five steps to get Aboriginal etiquette right, to reconcile and to become one.

Ⅰ. Introduce yourself appropriately

Julie Nimmo says, “When I introduce myself to other Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, it is important to say what people and family I belong to. When we talk about family, we talk about our ancestors from the past, but when we meet people from another country, we often introduce ourselves as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander or Aboriginal Australians”. Thomas Mayo said, “I would introduce myself as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander because of family ties. Torres Strait Islanders are more closely related to Pacific Melanesians, and Aboriginal Australians are from the Australian continent, and we have different cultures and languages.

- Never abbreviate

Properly refer to Aboriginal people by referring to Australia’s first inhabitants through terms such as ‘Aboriginal’, ‘native’, ‘Torres Strait Islander’ and ‘land’, with the first letter of each title capitalized as a sign of respect. Never abbreviate the terms Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander and avoid using acronyms or other pejorative terms that were used in colonial times, as this can really offend Aboriginal people. Do not use acronyms such as “ATSI”, which is an abbreviation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and has historically been used as a pejorative insult to Aboriginal Australians, who are very particular about what they call themselves and can be deeply hurt by hearing offensive terminology.

III. Welcome Ceremony

Before the event begins, people participate in a traditional Welcome to Country ceremony or an Acknowledgement of Country ceremony. The two ceremonies are different. The former is a very important sacred ceremony, conducted by an Elder of the place where you are, welcoming the participants to commemorate the past, and may take the form of speeches, dances, or fireworks. The latter ceremony, which can be conducted by anyone, is an important welcome offered at important meetings. No matter where we come from, we still belong to the land, and recognizing and thanking our guardians and elders shows that we know and respect the land. In the old traditions, an Elder was a respected member of the community who had reached a certain age and had the cultural and intellectual wisdom to teach the people moral behaviour. Elders were usually referred to as “Aunty” and “Uncle” (aunt and uncle) as a sign of respect, and non-indigenous people had to first seek permission to use these titles.

- Don’t judge a person by his or her appearance

Never question or assume a person’s Aboriginal identity based on physical appearance. Many Aboriginal people are survivors of the Stolen Generation. Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their homes between the 1910s and 1970s. Thomas Mayo said, “It is offensive to ask Aboriginal people about the percentage of their Aboriginal ancestry because the colonizers were trying to assimilate us in this country by reproducing us so that we eventually disappeared. 2008 Prime Minister Rudd apologized to the nation: ”On behalf of my government, I am sorry! On behalf of my government, I am sorry! People were criticized for the colour of their skin, this was called the assimilation policy, where a percentage of Aboriginal blood was measured so that the government could define a person as no longer Aboriginal, but now white. In fact, as long as these people have any Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander blood in them, we will consider them Aboriginal, or Torres Strait Islander, because it’s about connection to the Nation’s land, and it’s just as much about what heritage we still have”.

- Don’t be an advocate

Let’s show respect by knowing and understanding Aboriginal culture and never speaking on behalf of Aboriginal people. In order for us to move forward in a very positive and respectful relationship with each other, it is important to listen deeply, but we can also ask questions, as long as they are respectful and come from a place of genuine interest in learning. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a deep knowledge of the land, and by passing on their stories, protocols, ceremonies, and caring for their land – the land, the sea, the waterways, and the sky – through oral traditions, we can learn a great deal about caring for the environment.

I hope that through SBS’s detailed and heart-warming tips, Chinese Australians will recognize, understand and respect Aboriginal cultures, and think about how to contribute to the realization of reconciliation and the integration of Australia’s diverse cultures and ethnicities. After all, Chinese culture is a melting pot of thousands of years of history!

You may like

Features

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Published

4 days agoon

September 29, 2025

Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan embarked on her first visit to China since taking office, from September 14 to 19, lasting five days. Her itinerary included Beijing, Shanghai, as well as Victoria’s sister cities Nanjing, Chengdu, and Deyang. Accompanied by Labor MPs, she met with Chinese officials and business leaders. The focus was on boosting trade, promoting education exchanges, expanding the tourism market, and attracting more Chinese students and investment, with the aim of raising Victoria’s profile in China.

Is Victoria’s Relationship with China Over?

China has long been Victoria’s largest trading partner and the main source of international visitors. Allan’s office framed this trip as “the beginning of a new golden era” and emphasized that the purpose was to rebuild friendship with China.

Looking back, former premier Daniel Andrews had strongly promoted cooperation with China and even signed the “Belt and Road” agreement in 2018. However, the federal government later exercised its power under the Foreign Arrangements Scheme Act for the first time, canceling two agreements Victoria signed with China, citing inconsistency with Australia’s foreign policy or harm to foreign relations. This move provoked strong dissatisfaction from Beijing, with China’s Foreign Ministry harshly criticizing Australia for having “no sincerity in improving China–Australia relations.”

Subsequently, relations between China and Australia deteriorated further due to multiple controversies. Australia criticized Beijing’s actions regarding Hong Kong protests and human rights issues in Xinjiang, and supported the World Health Organization’s independent investigation into the COVID-19 outbreak. Meanwhile, Australian intelligence agencies exposed China’s attempts to influence local politics through political donations, sparking national security concerns. These events further strained bilateral ties.

Even so, Victoria tried to maintain exchanges with China, establishing sister-city relationships with several Chinese cities and consolidating ties through education and business cooperation, attempting to preserve collaboration within an otherwise tense climate.

But compared with Andrews’ “pro-China” image, Allan faces a more delicate situation. After stepping down two years ago, Andrews turned to private business, becoming a consultant with close links to Chinese enterprises. More recently, he even appeared at a military parade in Tiananmen Square and was photographed with President Xi Jinping and other Chinese leaders, sparking controversy. As the current premier, Allan has said, “”Victoria is an old friend of China and these connections are so valuable for our state,” but she must strike a far more cautious balance between cooperation with China and domestic political sentiment.

Judging by the arrangements of this visit, China’s reception of Allan was clearly not on par with that of Andrews in the past. She only met with Minister of Education Huai Jinpeng, and her first policy speech was held merely at a hotel. This treatment was far less prestigious than Andrews’ high-level invitation to witness the Tiananmen parade just a week earlier. Observers speculate that Beijing attaches limited importance to the current Victorian government, possibly because the “Belt and Road” agreements were overturned by the federal government, or due to the broader backdrop of strained China–Australia relations.

The Contradictions of Education Diplomacy

One major highlight of this trip was to deepen education cooperation. In its newly released Victoria’s China Strategy: For a New Golden Era, the Victorian government pointed out that in 2024 the international education industry contributed as much as AUD 15.9 billion to the state’s economy, remaining Victoria’s largest service export for more than two decades. Among this, Chinese students numbered 64,000, making China the largest source country. The document listed “continue to strengthen our reputation as a preferred destination for Chinese visitors, students, researchers, and investors” as a strategic priority, emphasizing the need to further consolidate Victoria’s image as a global destination for Chinese tourists, students, researchers, and investors.

When meeting Chinese Education Minister Huai Jinpeng in Beijing, Allan repeatedly stressed Victoria’s welcoming attitude toward Chinese students, hoping to expand bilateral exchanges through stronger educational cooperation and demonstrating the importance she attaches to “education diplomacy.”

However, this proactive approach sharply contrasts with federal policy. In August 2025, the Australian federal government announced a new student quota system, capping the total number of international students nationwide at 295,000 in 2026. Although this figure was 25,000 higher than the current year, industry insiders believe that due to persistent restrictions in the immigration system, actual numbers are unlikely to reach the cap. This runs counter to Victoria’s slogan of “saying yes to international students,” revealing a clear policy gap between the state and federal levels.

Under this contradictory framework, Victoria’s efforts to deepen cooperation with China through education remain constrained by federal policy, making it difficult for the state to achieve significant breakthroughs on its own. With the failed Belt and Road experience still fresh, it is understandable why Beijing did not devote much attention to the current premier. Against this backdrop, Allan could only meet with China’s education minister, raising doubts about how much real progress could be made.

Underwhelming Economic and Trade Outcomes

Just as politics offered little warmth, business results also proved lackluster. Many expected one of Allan’s key goals would be to seek Chinese funding for the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL) project, which faces a massive AUD 34 billion funding shortfall. This expectation was heightened by the fact that the rail line runs through electorates represented by several members of the delegation.

Yet, only a handful of business meetings were reported, with few major corporations participating. The visible results amounted to just two announcements: a solar energy cooperation project at the beginning of the trip, and at the end, the purchase of four tunnel boring machines (TBMs) from Chinese manufacturers for the SRL project.

The former was limited in scale and faced local criticism—during construction the project would create only about 60 temporary jobs, and after completion just six permanent positions, with minimal local employment benefits and potential environmental impacts.

The latter, although Allan made a point of visiting tunnel works in Deyang, Sichuan, and staged photo opportunities to emphasize Victoria’s cooperation with China, was essentially “spending money on imports.” While buying Chinese TBMs secured equipment for the SRL, it raised questions: why not develop or support such technology domestically, creating local jobs and industries, instead of sending huge sums abroad?

In other words, these arrangements mostly involved one-way capital outflow, without bringing in real foreign investment or capital inflows. The outcomes fell short of expectations for “attracting Chinese investment,” leaving only purchases and symbolic cooperation. With political recognition lacking and economic results unimpressive, what substantive benefits did this trip actually deliver for Victoria’s economy?

Economic Diplomacy or Electioneering?

For Allan, the trip was something of a dilemma. As premier, she could not avoid going to China during her term. But at the same time, she surely knew it would be hard to achieve real breakthroughs. The result was like a salesman being ignored despite enthusiasm, or a poor relative knocking on doors only to be turned away. Why, then, did Allan still lead a high-profile delegation to China?

Funded by taxpayers at an estimated cost of several hundred thousand dollars, the delegation did not include a single minister—only MPs from electorates with large Chinese or multicultural populations. They included Parliamentary Secretary and Box Hill MP Paul Hamer, and four Labor backbenchers: Meng Heang Tak (Clarinda), Mathew Hilakari (Point Cook), Matt Fregon (Ashwood), and John Mullahy (Glen Waverley).

According to the 2021 census, Victoria has around 500,000 residents of Chinese descent, a significant share of the state’s 7 million population. In these key electorates, Chinese voters number in the tens of thousands, enough to influence electoral outcomes. While these accompanying MPs may have little policy influence, they are politically important. This raises questions over whether Allan’s visit was more about connecting with the Chinese community ahead of the November 2026 state election, consolidating a large and crucial voter bloc. Rather than an economic diplomacy mission, it may have been a campaign-style political tour.

The trip delivered limited results, with symbolism outweighing substance. Allan brought back no new investment and no major corporate commitments, while her accompanying MPs became the focus. What can these powerless backbenchers actually bring to Victoria? Do they signal attention to multicultural communities and bolster diplomatic credentials? Or was this merely a “taxpayer-funded election show,” with taxpayer money spent on photo ops in China to build momentum for the next election? Anyone with a bit of political sense can see through it.

Multicultural Development

Just before the trip, the Victorian government released the Victoria’s Multicultural Review, regarded as the most significant policy reform in decades. Led by George Lekakis AO and an expert advisory group, it drew on 57 community meetings, consultations with over 640 residents, and input from more than 150 organizations and community groups. The goal was to strengthen social cohesion and rebuild trust between the government and multicultural communities. The report was released on September 11 by Allan and Minister for Multicultural Affairs Ingrid Stitt.

Core recommendations include establishing a new statutory agency, Multicultural Victoria, headed by a Multicultural Coordinator General, supported by two deputies (one from a rural area), and advised by a five-member commissioner panel. This structure would replace the largely ceremonial Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC), which for years was limited to public relations without significant policy impact.

Following the review’s release, Allan quickly linked “multiculturalism” with the Chinese community. On September 12, in her hometown Bendigo, she announced nearly AUD 400,000 in funding to upgrade the Golden Dragon Museum into the “National Chinese Museum of Australia.” This symbolic move not only highlighted Bendigo’s historical ties to Chinese immigrants during the gold rush but also aimed to strengthen the cultural status of the Chinese community in Victoria.

Other funded projects included the Mingyue Buddhist Temple in Springvale South, the Avalokiteshvara Yuan Tong Monastery underground car park in Deer Park, the Museum of Chinese Australian History in Melbourne CBD, and infrastructure and lighting upgrades at the Chinese Association of Victoria Inc in Wantirna. These investments enhance cultural facilities and directly address community needs.

Is Multiculturalism a Political Tool or Genuine Goal?

This raises the question: are Allan’s initiatives genuinely aimed at fostering social cohesion, or are they part of political calculation? Victoria has long led the country in multicultural policy, but its political functions are also significant. During Andrews’ era, “multiculturalism” was used to package economic cooperation with China, drawing criticism of “national security risks” and “overdependence.” Allan now continues this approach but faces cool responses from Beijing and skepticism from the opposition and media at home.

Still, Allan’s strategy is not identical to Andrews’. Unlike the 2016 version of the “China Strategy,” her policy no longer emphasizes export figures or the economic benefits of the Belt and Road, but instead focuses more on cultural exchange and community engagement, encouraging Chinese-Australians to actively shape interactions with China. This shift highlights interpersonal and cultural connections rather than purely commercial transactions.

She has repeatedly wrapped her policies in “personal stories”: from Beijing to Nanjing to Shanghai, she promoted not just Victoria’s universities, tourism, and agricultural products, but also the importance of shared history, language, and culture. When meeting Education Minister Huai Jinpeng, she mentioned that her 13-year-old daughter is learning Chinese, to foster relatability.

Thus, Allan’s “multicultural strategy” carries two possible meanings: on one hand, it shows a sincere wish to improve social cohesion and strengthen ties with the Chinese community; on the other hand, it inevitably serves political calculation and election mobilization. As the 2026 state election approaches, Allan’s ability to convince both the Chinese community and the broader electorate that this is more than just political maneuvering but a genuine social vision will be a critical test of her leadership.

Still Unresolved: Practical Needs of Multicultural Communities

Even if Allan today offers small grants or gestures of goodwill toward the Chinese community, they pale in comparison to Andrews’ campaign promises in 2014 and 2018, when he pledged nearly AUD 20 million for the Chinese and Indian communities to purchase land for building aged care facilities. These two groups are now Victoria’s largest multicultural communities, and both place high cultural importance on caring for elders. Whether the elderly receive proper care in later life is a vital issue.

In 2018, the Australian government noted that as people live longer, the number of dementia patients is surging. For non-English-speaking elderly migrants—many of whom either never learned English or lose it due to dementia—the need for care in their native language and cultural context is especially acute. Yet mainstream services remain unwilling to provide such care. Therefore, the government has a responsibility to help minority communities build appropriate aged care facilities. Andrews recognized this situation and made it a campaign pledge.

But to this day, the Victorian government has only “purchased” the land and has not handed it over to community groups to build facilities—an 11-year failure that could be seen as the biggest “betrayal” of minority communities in Victorian history. By appealing to immigrant communities that value elder care, Andrews gained their votes to govern Victoria, but apparently never intended to deliver on his promises. It was a shameless act. Yet after Allan took over, she did not address the issue. Worse, last year she changed project rules, stripping Chinese and Indian community organizations of eligibility to apply to build aged care homes.

Clearly, the Allan government’s actions today sharply contradict its rhetoric about promoting multicultural development. This is likely to become a key concern for multicultural community voters in next year’s state election.

Features

From Everyday Pressure to Identity Anxiety: The Social Fault Lines Behind Anti-Immigration Marches

Published

3 weeks agoon

September 11, 2025On August 31, major Australian cities, including Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Adelaide, Hobart, and Perth, simultaneously saw anti-immigration demonstrations under the banner “The March For Australia.”

The organizers rallied around the slogan “Oppose Mass Immigration”, claiming that immigrants were crowding housing and economic resources. In Melbourne, about 1,000 people participated, while Sydney saw a much larger turnout of 5,000 to 8,000 people. Marchers waved Australian flags, chanted “Australia”, and some shouted exclusionary slogans like “Go back” and “Stop the invasion.”

For newly arrived immigrants—or even residents who have already settled—such scenes were not only confusing but also alienating. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese pointed out in an interview that apart from Indigenous Australians, all Australians are either immigrants or descendants of immigrants. Australia’s history is rooted in Indigenous culture for tens of thousands of years, while large-scale European colonization has profoundly shaped modern Australian society. In other words, many of the demonstrators themselves may be descendants of immigrants—so why do they hold such strong anti-immigrant sentiments?

Anti-Immigration Marches Driven by Far-Right Ideology

The “March For Australia” was partly triggered by the “March for Humanity” pro-Palestinian demonstrations on August 3. On that day, Sydney saw 200,000–300,000 participants, with similar rallies in other cities. The marches were marked by Palestinian flags, some waving Hamas banners, and even portraits of Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei. These scenes stoked anxiety among some citizens about “foreign immigrants,” setting the stage for the anti-immigration march.

The organizers of “March For Australia” identified themselves as “patriots” or “ordinary Australians,” advocating against “mass immigration” and for the protection of national culture and identity. They heavily promoted the event on social media platforms like TikTok, X, and Facebook, emphasizing “only wave the Australian flag, no foreign flags” and using “Defend Australian values” as a slogan.

However, the march quickly drew criticism from the government and public opinion as “spreading hatred and dividing society.” One reason is the organizers’ links to far-right forces. According to the ABC, their website once cited the far-right white nationalist concept of “remigration”—calling for the large-scale deportation of non-European immigrants—and even featured pro-Nazi and Hitler memes. Although later removed, this suggested underlying far-right tendencies.

Controversy deepened with the public involvement of the neo-Nazi group National Socialist Network (NSN), which promotes white supremacy and anti-Semitism and openly idolizes Hitler. While organizers claimed they were only encouraging various groups to participate, NSN rhetoric and online platforms were easily co-opted by neo-Nazis and racists. On the day of the march, some NSN members shouted “Australia is for white people” and stormed Melbourne’s “Camp Sovereignty,” a symbolic Indigenous protest site, trampling flags and extinguishing sacred fires, accompanied by blatant racist slogans. This led mainstream media to label the march as far-right or even fascist.

A glaring contradiction arose: if the march’s core concern was social pressure from too many immigrants, why did some participants target Indigenous Australians and ethnic minorities? What could have been a debate on immigration policy turned into a stage for neo-Nazis exploiting social anxieties to promote white supremacy.

Moreover, the anti-immigration marches, under the guise of “patriotism,” unwittingly made some participants tools of neo-Nazi propaganda. For extremist groups, the immigration issue is just the easiest emotional lever; their true goal is to incite racial hatred and further divide society.

The Complexity of Participants’ Motives

The crowd was not monolithic. Besides hardline nationalists, there were residents genuinely concerned about the cost of living, including long-settled immigrants. In Sydney, when a speaker emphasized that “defending culture and lifestyle is not hatred,” the crowd cheered. But when a self-proclaimed “Australian white” leader called for a “new wave of nationalism,” some immediately voiced disapproval, shouting “This is hate speech!” and many left early. This demonstrates that even under the same “patriotism” slogan, legitimate grievances and extremist ideology coexist—highlighting the deep divisions within Australian society.

Notably, some first-generation immigrants participated in the anti-immigration march. They often distinguished between “low-skilled” or “illegal” migrants, whom they claimed could not integrate into Australian society, versus high-skilled or wealthy immigrants, whom they welcomed. This selective standard reveals hypocrisy: criticizing vulnerable groups from a position of relative advantage is still a form of xenophobia, and essentially, hate.

Perceptions vs. Reality of Immigration in Australia

Concerns over “mass immigration” were amplified during the “March For Australia”. Organizers emphasized worries over housing and economic resources but never clearly defined what “mass immigration” means. Australia has always been a nation of immigrants, and the perception of “too many immigrants” may not align with reality.

Data shows immigration has not continuously surged. According to the 2021 census, there were about 550,000 residents born in China, a 72% increase over a decade—but growth slowed to just 8% in the past five years. The Muslim population rose 70% between 2011 and 2021, but only from 2.2% to 3.2% of the total population. These groups remain a minority nationally, though their concentration in Sydney and Melbourne amplifies social perceptions.

The pandemic also played a role. Border closures temporarily reduced the number of international students and immigrants, but once borders reopened, net overseas migration (NOM) spiked to 340,000, mostly concentrated in Melbourne and Sydney. This compounded housing shortages and rising living costs, fueling social anxiety.

The Lowy Institute’s June 2025 national survey found that 53% of Australians believed immigration levels were “too high,” up 5% from the previous year; 38% saw it as “appropriate,” and only 7% said “too low.” Anxiety about “too many immigrants” is real—but the root issue may lie in chronic shortages of housing and infrastructure.

Population Growth and Pressure on Social Resources

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, net migration reached 446,000 in the year to June 2024, including 207,000 international students mostly on temporary visas. This population inflow strains public healthcare, education, transport, and social services: emergency wait times rise, classrooms are overcrowded, and public transport becomes congested. These pressures fuel public concern and skepticism of government planning.

However, the problem isn’t simply “too many immigrants,” but the gap between population growth and infrastructure planning. During the pandemic, net migration fell below zero, yet housing prices continued to soar, and healthcare and education systems remained under pressure. The post-pandemic rebound pushed net migration above 500,000 in 2023, largely from returning students and temporary workers. The challenge is whether government planning and investment can keep pace with population change.

Following the anti-immigration protests, the federal government announced on September 2 that the 2025–26 permanent migration program would maintain 185,000 spots, focusing on skilled migrants and family reunification. To “manage student numbers more sustainably,” the international student cap will rise to 295,000 in 2026.

From July 1, 2024, the government ended the 485 visa extension policy: bachelor’s and master’s graduates can stay a maximum of 2 years, research masters and PhDs up to 3 years. English proficiency requirements and visa fees increased. Previously, many 485 visa holders could extend automatically, even without permanent residency prospects, swelling the temporary resident population. Many worked low-skilled, low-wage jobs, further stressing social resources and labor markets.

The Labor government is gradually addressing these issues to better align immigration levels with resources. If measures succeed, gaps between population growth and social infrastructure could ease.

The Role and Contribution of Immigrants

Three common complaints about immigrants are: they depress wages, take jobs from locals, and drive up housing prices. While simple and catchy, these claims do not hold up to scrutiny.

Immigrants support key sectors in Australia. Healthcare has long faced labor shortages; international medical staff fill gaps. Technology, engineering, and IT sectors rely on overseas graduates for skills and innovation. Immigrant entrepreneurship creates jobs, benefiting locals and other migrants, fueling economic growth. Immigrants often sustain employment markets rather than “steal jobs.”

New migrants do face challenges, including language barriers, cultural adjustment, and job competition. Attributing employment pressure solely to immigrants ignores the difficulties they endure.

Regarding housing, data shows that during the pandemic, when immigration was at a century-low, house prices still soared—indicating that low interest rates, investment demand, land shortages, and rising construction costs were the main drivers. Population growth contributes to demand but is not the primary cause of high prices.

Anti-Immigration Sentiment and Australia’s Challenge

Immigration policy in Australia is both an economic necessity and a sensitive social issue. The anti-immigration marches exposed this tension: peace and violence, legitimate concerns and extremist ideology coexist.

As Federal Minister for Multicultural Affairs Anne Aly noted, far-right and neo-Nazi groups exploit real anxieties about housing and cost of living to spread hatred and xenophobia. Historically, blaming immigrants for housing and infrastructure issues has precedents—without clarification, such tendencies risk repeating.

The government also bears responsibility. Immigrants from diverse backgrounds have long been part of society, and associated issues are not new. Overreliance on specific source countries, inadequate regulation of international students staying on temporary visas, and lack of systemic planning for third-country immigrants are policy gaps. These delays turn structural problems into simplified “immigration issues,” which extremists exploit. Without improving resource allocation and planning, anti-immigration sentiment will deepen societal division.

In the long term, Australia’s true challenge is not simply “too many immigrants,” but balancing population pressure with multicultural integration. The historical White Australia Policy left a deep xenophobic imprint. Today, the government must strengthen housing and infrastructure planning and promote education and multicultural understanding to genuinely achieve the ideal of a diverse, inclusive Australian society.

Features

“Medisafe” Award Sparks Controversy; Debate Lasts Several Months

Published

3 weeks agoon

September 11, 2025Medisafe, developed by Pan Xichun, daughter of international liver cancer expert and honorary professor of surgery at the University of Hong Kong Pan Dongping, has participated in multiple major Hong Kong and international innovation competitions and won awards. However, it was challenged by Hailey Cheng, a second-year student in Computational Mathematics at City University of Hong Kong, who questioned the originality of the project, suggesting that Pan commissioned an AI company to develop Medisafe and entered it into competitions. This sparked months of controversy over “ethics and authorship.” Recently, Pan Dongping and his wife Peng Yongzhi issued a statement expressing willingness to relinquish Medisafe’s awards, though it remains unclear if this will temporarily end the months-long storm.

A Talented Young Student

Last year, Pan Xichun, a first-year student at the prestigious Saint Paul’s Co-educational College (SPCC) in Hong Kong, won numerous local and international awards for her AI project Medisafe. She received the Hong Kong ICT Award: Student Innovation Award, the Jury’s Special Commendation, and returned with honors from the Geneva International Invention Exhibition, earning media recognition as a “prodigy” and “future star of AI in healthcare.”

Medisafe is an AI-driven web application designed to assist hospitals and clinics in processing large volumes of prescriptions and connecting different medical departments, providing cross-hospital AI-assisted services for patients. The system cross-checks medications and patient databases to automatically verify allergies, long-term medications, and clinical conditions. It alerts medical staff if potential prescription or dosage issues are detected. In interviews after winning awards in April, Pan Xichun stated that the idea for Medisafe arose from news about medication errors. She emphasized that no similar system exists on the market that automatically compares prescriptions with patient medical records, claiming Medisafe as a first-of-its-kind concept.

Pan Xichun’s broader talents also highlight her capabilities: at 13, she founded a volunteer organization serving the community and earned recognition for musical talents. Previously, she created a system linking smart insoles to a mobile app to monitor hikers’ conditions and issue alerts, demonstrating creativity. Her outstanding performance from a young age is likely influenced by her family background, as her parents are established social elites.

Traditional Chinese educational philosophy stresses the role of parents and teachers as cultivators: “If a child is raised without proper teaching, it is the parent’s fault; if the teaching is not strict, it is the teacher’s laziness.” Pan Xichun’s early talents suggest her parents invested considerable effort in nurturing her abilities. From this perspective, it is hard to see why Pan Xichun’s parents should face criticism.

From Winning Awards to “Ethics Controversy”

The situation shifted quickly. On June 13, Hailey Cheng, a second-year student in computational mathematics at City University of Hong Kong and an undergraduate researcher in computational biology, posted on Threads questioning whether the project was solely Pan’s work. She also raised concerns about potential patient data leakage to third parties, citing privacy risks. This drew public attention: logging into Medisafe directed users to the AI Health Studio (AIHS) website, indicating clients included Pan Dongping and his brother Pan Dongsong’s Hong Kong Hepatopancreatobiliary and Colorectal Minimally Invasive Surgery Center. Subsequently, Medisafe became inaccessible.

As the controversy grew, AIHS co-founders issued a statement clarifying that in March of the previous year, they had been commissioned by Pan Dongping’s wife, Peng Yongzhi, to produce a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) for Medisafe. They emphasized the product was developed from scratch, with Pan Xichun providing only the initial idea, and that they were never informed it would be submitted to competitions.

Concerns arose over why an American AI company was hired. Peng Yongzhi explained that to prevent the concept from being copied or commercialized by others, she independently contacted the company in March of last year to explore developing a commercially viable product. In the same month, they were commissioned to develop the MVP for business feasibility verification. Competition organizers stress that entries must be original concepts created in Hong Kong, with participants holding intellectual property rights or legal ownership, and requested a full investigation by the Hong Kong Education City and the Standard Assurance Committee. Hong Kong Gifted Education Academy and Education City later confirmed that the platform was an original concept and that all awards would be retained. Nonetheless, controversies continued.

The Elite Mindset: Winning is Everything

In Hong Kong, a highly market-driven education system combined with entrenched social stratification makes competition extraordinarily fierce from the start. Children must not only learn early but also rely on substantial resources. Parental social status determines access to elite education, financial strength secures top-tier teachers, and extensive networks help package résumés. Education has become a precision investment: money, time, and strategy are invested, with expected returns in connections, résumés, platforms, and academic advancement. The Medisafe controversy offers a glimpse into this reality.

On a broader social scale, the Medisafe incident exposes a deep fissure in Hong Kong’s educational system: in a “competition-first” and “résumé-driven” environment, education becomes a theater for packaging success. The controversy is less about a “fallen prodigy” and more about public disillusionment with the “elite replication mechanism”—where awards reflect parents’ resources, connections, and wealth. Whether Pan Xichun is truly a genius or whether her family’s resources propelled her beyond societal expectations is now a topic of public debate.

Parents Step In

Recently, Pan Dongping and his wife announced they would relinquish all awards associated with Medisafe, citing their daughter’s mental and physical well-being as the priority. They acknowledged shortcomings in handling the situation, apologized for the disruption, and reaffirmed that Medisafe was Pan Xichun’s original concept. They also reserved the right to pursue legal action against false claims and malicious attacks online. Their statement reflects a protective parental stance, though it also reveals an elite mindset perceiving the world as being against their daughter.

In recent years, more than 4,000 Hong Kong students have participated in STEM competitions. Some schools even coach students “to win awards,” outsourcing development or fabricating research. This highlights the disparities in resources among families and raises questions of educational fairness. Education has become a contest of family background, capital, and packaging skills. The question arises: should children’s early growth aim to cultivate independent thinkers, empathetic and responsible individuals, or to produce elite performers following their parents’ scripts?

The Long Road Ahead

The most unfortunate aspect is the impact on Pan Xichun herself. Legally still a minor, she was thrust into a public controversy amplified by online discourse—a situation far beyond what a student should endure.

Online, critics labeled her actions as “academic fraud” or “winning awards through financial resources,” largely based on subjective assumptions without factual basis. STEM competitions are designed to encourage creativity and effort, not to judge minors by strict academic standards. Many online critics likely have no personal involvement in such competitions, but sensationalism elevated their importance beyond reason.

Pan Xichun’s parents hope relinquishing the awards will calm the storm, citing her extreme distress from online bullying. Rumors suggest she may take a year off school. Her recovery from this mental strain will vary and may leave long-term impacts. It is regrettable if public emotional venting hinders the development of an exceptionally talented young person.

However, the parents also criticized Hailey Cheng, asserting she was not a “well-intentioned whistleblower.” In reality, whistleblowers aim to raise public awareness, and their motives need not be “good-willed.” Critiquing social mechanisms often prompts backlash, but this does not invalidate whistleblowing. Cheng consistently updated the situation online since June, reportedly facing online and real-world harassment, including anonymous threats, which is also unacceptable.

After Pan’s parents announced relinquishing the awards, Cheng noted that their decision was not due to competition rules or originality disputes but primarily to protect their daughter’s health, highlighting how formal mechanisms often fail while online discourse pressures change. This reflection raises questions: can evidence, rules, and facts truly drive investigations, or only public pressure and online debate? Elite families may perceive rules and evidence as tools to climb social ladders—until public scrutiny, particularly online, challenges their arrogance.

When competitions intended to promote innovation and discover young talent become contests of academic resources and connections, one must ask: how much space remains for ordinary children to advance? Family legacy requires generational continuity, but when social mechanisms reinforce inequality and disregard basic fairness, whistleblowing deserves attention.

Listen Now

QantasLink Considers Closing Staff Bases in Canberra, Hobart, and Mildura

ACMA Issues Warning to “The Kyle and Jackie O Show”

British Primatologist Jane Goodall Passes Away

NSW Police Urged to Stop Strip-Searching People

Israeli Navy Intercepts “Global Sumud” Aid Flotilla; Greta Thunberg Detained

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

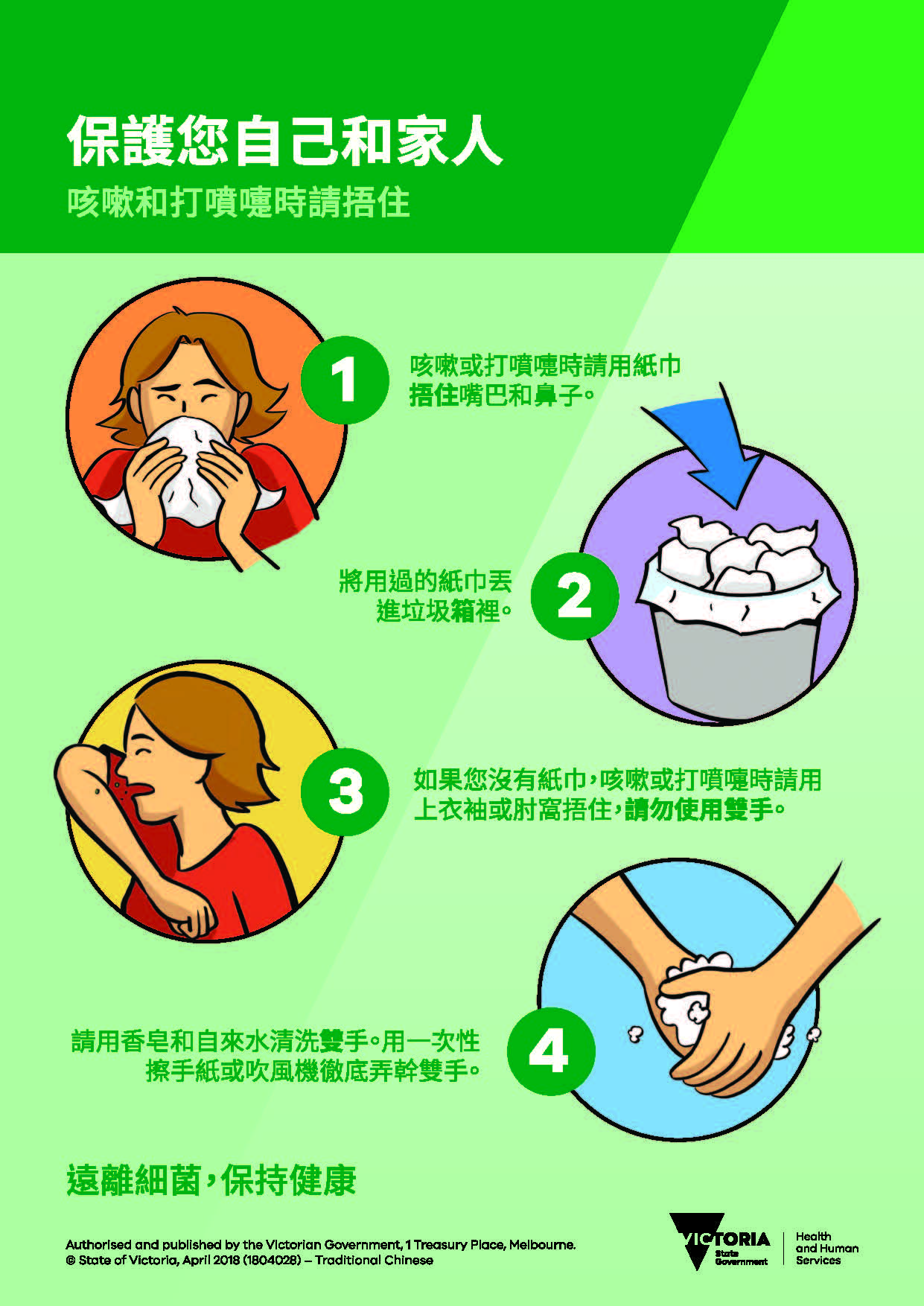

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

U.S. Investment Report Criticizes National Security Law, Hong Kong Government Responds Strongly

China Becomes Top Destination for Australian Tourists, But Chinese Visitor Return Slows

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Albanese Visit to UK Focuses on Domestic Reform, Not Republican Debate

Optus Faces Another “000” Outage, Singtel Bonus Sparks Controversy

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保護您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打噴嚏時請捂住