Features

The Impetus Behind “Thriving Kids”

Published

16 hours agoon

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was designed as a support program for people with disabilities, with autistic individuals being one of its major beneficiary groups. According to statistics, approximately 290,900 Australians are autistic, meaning roughly 1 in every 90 people falls on the autism spectrum. Among children and adolescents under the age of 25, the prevalence of autism is significantly higher than in the adult population.

Since its implementation, many parents have become heavily reliant on the funding and assistance provided by the NDIS. For some families, it represents their only source of meaningful support. In August last year, the government proposed the Thriving Kids program, though details remained vague for an extended period. After a long period of stagnation, a full policy framework was finally released this year. However, the more pressing question is this: to what extent have Australian parents come to treat disability-related programs for children as a central pillar of support—and to what extent has the government itself encouraged this dependency?

The Background of NDIS and Thriving Kids

The NDIS was originally designed to support individuals with long-term, severe, and permanent disabilities. However, during implementation, its scope expanded rapidly. A large number of autistic children and children with developmental delays entered the scheme, causing participation numbers and costs to far exceed initial projections and placing significant financial strain on the government.

In response, and in an effort to return the system to its original focus on significant and permanent needs while addressing fiscal sustainability, the Australian government announced a new support model—Thriving Kids—in August 2025. This program forms part of the broader “Foundational Supports” framework and is designed for children aged eight and under with low to moderate support needs, including developmental delay or autism.

Thriving Kids emphasizes early identification, information linkage, parent guidance, and timely professional intervention, without requiring a formal disability diagnosis or long-term individualized plans. The federal and state governments jointly committed approximately $4 billion to the initiative. The program is scheduled to begin rollout in October 2026, with full implementation by January 2028. Following this, eligibility criteria under the NDIS Act will be progressively revised so that children with low to moderate needs are redirected to Thriving Kids, while children with severe and significant functional impairments remain supported under the NDIS.

Unlike the NDIS’s annual individualized funding packages, Thriving Kids prioritizes community-based early intervention, delivered through schools, early childhood centres, and local health services. The intent is to provide families with earlier, more practical support, reduce reliance on complex diagnostic processes, and ease long-term financial pressure on the NDIS. The program was designed by the Department of Health with an expert advisory group chaired by pediatrician Frank Oberklaid, alongside consultations with disability advocacy groups and family representatives.

It is important to note that Thriving Kids was not directly completed under Bill Shorten’s leadership. While Shorten was a central architect of the NDIS and promoted the concept of “foundational supports,” he announced his departure from federal politics in September 2024 and stepped down in February 2025 to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Canberra. The concrete design, naming, and implementation of Thriving Kids were formally announced and advanced in 2025 by his successor, Health Minister Mark Butler.

Despite its intentions, the foundation of Thriving Kids is not entirely sustainable. Limited resources, broad coverage, and reliance on intergovernmental and local coordination place long-term strain on the system. This indirectly encourages some parents to offload responsibilities that would otherwise fall within ordinary parenting onto formal support structures, fostering dependency on Thriving Kids or similar subsidies.

The Pathologies of Parental Dependence

A persistent belief in society holds that as long as parents secure the “best possible support,” autistic children will naturally lead happy lives. This assumption is fundamentally flawed.

Recent data show that children aged 5–7 account for approximately 11–12% of participants in relevant programs, with a high proportion diagnosed with autism. This figure far exceeds historical trends, driving NDIS costs upward to unsustainable levels. Some government officials have bluntly acknowledged that many children were included simply because parents believed this was the only way to obtain support. This implies that not all approved cases genuinely require intensive, long-term resources; rather, parental anxiety combined with institutional incentives has driven a rush to secure whatever assistance is available.

Why are parents so eager to be “first in line”? The answer lies in the chronic delays within the public education and healthcare systems. Comprehensive assessments through public child development services typically take 6 to 24 months, and in some cases over three years. Even after GP referral and initial contact within six weeks, full assessments and meaningful intervention involve long waiting lists. In this context, the NDIS becomes the only system capable of delivering immediate, tangible assistance—speech therapy, occupational therapy, assistive devices, and sensory regulation tools. Over time, parents internalize the belief that failure to enter the system means falling behind entirely, leading to growing reliance on subsidies and gradual withdrawal from active parenting responsibility.

This is where the problems begin.

In extreme cases, parents come to treat the NDIS as an all-encompassing caregiver, outsourcing the roles of therapist, educator, and support system. Understandable justifications are often cited—caregiver exhaustion, lack of family support, or absence of non-institutional resources—resulting in a mentality of “since services are involved, I no longer need to intervene as much.” The outcome is predictable: children struggle socially, behavioural issues escalate, and teachers and peers bear the consequences. Parents then attribute these outcomes solely to “autism itself,” rather than reflecting on the effects of excessive outsourcing and responsibility transfer. Over time, children become institutionally labelled without acquiring real-world adaptive skills.

When children grow up embedded in highly institutionalized service pipelines—continuous assessments, therapies, reports, and reassessments—they learn not how to navigate social situations or self-adjust, but how to wait for instructions and passively respond to professionals. This environment steadily erodes autonomy and problem-solving capacity, particularly for high-functioning autistic individuals. These children often have genuine potential to learn social rules and adapt behaviour, yet are conditioned to function only in therapy rooms, becoming helpless once professional scaffolding is removed. Ultimately, they internalize a dangerous message: “I cannot live without experts.”

Within this framework, every emotional outburst, refusal, or mistake is easily interpreted as further evidence that “more intervention is needed.” Normal developmental behaviours that could have been guided and corrected are prematurely pathologized. This deepens parental anxiety and leads children to internalize the belief that they themselves are fundamentally defective, eroding self-esteem and self-efficacy. Some children even develop dependency patterns: when discomfort or frustration arises, they expect external agents to “fix the problem,” weakening self-regulation and accountability while intensifying parent–child conflict.

Another direct consequence of excessive service intervention is the hollowing out of the parental role. Daily routines, emotional guidance, and boundary-setting—core elements of parenting—are increasingly delegated to therapists, social workers, or support staff. Over time, parents’ understanding of their children becomes fragmented, reduced to diagnostic labels and professional jargon, while intuitive knowledge built through daily interaction is lost. When services are interrupted, reduced, or transitioned, these families become more fragile and conflict-prone, unsure whether they even know how to parent anymore.

More troubling still, overreliance on services leads to the “gentle abandonment” of high-functioning autistic children. As children become more withdrawn, some parents choose accommodation over guidance—avoiding challenges, discouraging risk-taking, and prioritizing surface-level emotional calm. As a result, children’s social worlds shrink, and remaining developmental potential in socialization, adaptability, and self-management is slowly stripped away. Support transforms from a tool into a substitute; from a bridge into a protective shield that blocks growth. The most devastating consequences often emerge only in adulthood, when institutional support fades and individuals find themselves unable to cope with unstructured reality—not due to lack of ability, but because they were never allowed to practice independence. The cycle then repeats in the next generation.

Compounding this problem is the reality that many children receiving services may simply be developing at a slower pace, rather than having long-term, severe impairments. In a system heavily dependent on diagnoses and subsidies, developmental variation becomes over-medicalized. Temporary delays are treated as permanent deficits, diverting substantial resources toward children who might otherwise catch up naturally. Meanwhile, individuals with severe autism or multiple disabilities—those who truly require intensive, lifelong support—are pushed aside, delayed, or overlooked in resource competition. When limited public funds are used to soothe anxiety and patch systemic gaps rather than meet actual need, the entire support system loses fairness and strays from its original purpose.

Support Without Indulgence

An effective support system should strengthen families, not replace them. Government services must function as tools, not long-term substitutes. The core objective should not be the number of therapy hours delivered, but a clear delineation of which supports are temporary and which responsibilities must ultimately return to families and children.

First, support must prioritize parent capacity-building, not one-way resource delivery. Rather than indiscriminately outsourcing services, funding should focus on parent training, behavioural guidance, and in-context coaching. Community-based parent–child workshops can teach positive behaviour management strategies and simulate social scenarios where parents observe and guide in real time. When parents acquire these skills, children’s progress in social interaction, emotional regulation, and self-management becomes more stable and transferable to school and community settings. Success metrics should shift from service completion to parental independence.

Second, systems must include clear exit mechanisms and staged goals. All support plans should have defined timelines and transition points, with regular evaluations of readiness for reduced services and increased autonomy. A high-functioning autistic child, for example, may achieve sufficient self-regulation and basic social interaction after six months of parent-led guidance and light intervention, at which point professional involvement should be gradually reduced. Systems without exit strategies merely manufacture lifelong dependency.

Third, policy must clearly differentiate responses to developmental delay versus long-term disability. Support for the former should be light, short-term, and centred on families and schools; the latter requires stable, long-term resourcing. Accurate triage ensures that high-need groups receive priority while preventing low-need children from becoming service-dependent through over-intervention. Evidence consistently shows that misallocation of resources undermines equity and harms those most in need.

Finally, systems must reaffirm an uncomfortable but essential truth: support is not a replacement for parenting. No policy can substitute for parental presence. A healthy support ecosystem expects parents to re-engage, not retreat. Support should act as a bridge, not a shield—enabling children to develop independence, tolerate frustration, and explore the world.

Parental dependence, excessive service intervention, and resource misallocation are not merely side effects of one policy, but symptoms of a broader societal immaturity in understanding responsibility, care, and public resources. If support systems provide subsidies and substitution without demanding parental accountability, children’s autonomy will erode and high-need populations will be neglected. Policymakers must recognize that the purpose of support is empowerment, not replacement. Families, communities, and public systems must complement—rather than substitute—one another. Without this balance, even the most carefully designed programs such as Thriving Kids or the NDIS will only fill short-term gaps, failing to cultivate independence or long-term wellbeing for autistic individuals.

You may like

Europe has long been regarded as a major collective of world powers. Yet since the Second World War, its strength has been significantly diminished. In seeking self-preservation, Europe chose unity through the creation of the European Union. However, today the drawbacks are becoming apparent before the benefits—and Australian media largely remains indifferent.

This raises a fundamental question: under conditions of internal fragmentation and external constraint, is the EU still a political entity capable of pooling sovereignty and amplifying influence, or has it already become synonymous with compromise, delay, and structural impotence? And what do Europe’s internal conflicts have to do with Australia?

Europe Is Not a Single Country

To understand Europe’s current condition, one basic fact must be acknowledged: Europe is a continent composed of many states, nations, and cultures, not a unified country. From the territorial expansion of the Roman Empire, to Napoleon’s conquests, to Hitler’s ambitions during the Second World War, Europe has repeatedly seen attempts at unification or domination by a single power. Yet such unity was built on force, political coercion, or temporary alliances, and failed to eliminate cultural differences, historical grievances, and conflicts of national interest. As a result, these attempts at European unification collapsed quickly.

Even in the modern era, the European Union cannot fundamentally alter this reality. Each member state retains its own historical trajectory, political system, and foreign policy priorities. Germany’s energy dependence, Hungary’s Russia policy, France’s pursuit of strategic autonomy, and the economic strategies of Nordic countries all reflect divergent core interests. Despite the presence of a supranational organization like the EU, Europe remains a diverse, complex, and often divided entity rather than a unified force driven by a single will.

For this reason, reducing Europe to a “unified front,” or allowing Britain and France alone to stand in for the entire continent, ignores historical lessons and underestimates the complexity of contemporary international politics. Australia’s continued reliance on this simplified perspective risks misjudging allies’ positions and creating blind spots in diplomatic, military, and economic strategy.

The EU’s Unstable Foundations

Understanding the European Union requires recognizing that it did not emerge overnight, but evolved over more than half a century on inherently unstable foundations.

After the Second World War, Western European states—devastated by conflict—sought cooperation to prevent another major war. This began with the European Coal and Steel Community, which gradually developed into broader economic integration. The 1957 Treaty of Rome established the European Economic Community (EEC), strengthening trade, tariffs, and market integration, and laying the groundwork for political union. Following the end of the Cold War, the 1992 Maastricht Treaty formally created the European Union, expanding economic cooperation while proposing a common foreign and security policy and preparing for the introduction of a single currency, the euro.

This integration process was far from smooth. As membership expanded from the original six countries to more than twenty, vast differences in historical background, economic structure, and national interest became increasingly pronounced. While this diversity helped make the EU the world’s largest single market and a major political-economic bloc, it also embedded high decision-making costs and chronic difficulty in reaching consensus. The United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum to leave the EU—formally completed in 2020—marked the first time a member state truly exited the bloc. Brexit not only reshaped Europe’s political and economic architecture, but also symbolized persistent tensions between globalization and national sovereignty.

These unresolved historical divisions continue to undermine the EU’s decision-making efficiency and cohesion, explaining why the bloc can appear powerful on the global stage yet often find itself constrained by internal fractures.

The Symbolism of the Greenland Crisis

The EU and the United States have long been viewed as close allies, bound by Cold War cooperation and NATO. Yet recent events surrounding Greenland demonstrate that even the strongest transatlantic relationships can fracture over strategic interests, resource control, and divergent diplomatic approaches.

The Greenland controversy has become one of the clearest examples of rising strategic tension between Europe and the United States. Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark located in the Arctic, holds significant military and resource value. After returning to political prominence, US President Donald Trump publicly expressed a desire to “own” the island, suggesting economic or other pressure on allies and even threatening to impose a 10% import tariff on eight European countries opposing US control of Greenland. This provoked strong backlash across Europe and sparked protests in Denmark and Greenland, including mass demonstrations in Copenhagen under slogans such as “Greenland is not for sale.”

The EU and multiple European leaders responded swiftly, affirming Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland and calling for respect for international law and basic trust among NATO allies. Senior EU officials and national leaders emphasized dialogue while also signaling the potential use of the EU’s “anti-coercion instrument” to counter possible US trade threats.

This crisis was not merely a territorial dispute; it symbolized deeper cracks in the transatlantic alliance. Where NATO and shared security frameworks once ensured cohesion, unilateral US actions have now generated open resistance among European allies, forcing the EU to reconsider its own strategic autonomy. Some European politicians have openly argued that Europe must reduce its dependence on the United States in foreign and security policy.

The Greenland episode underscores a broader reality: the “Western bloc” is not monolithic. Even military allies and trade partners can see cooperation unravel when interests diverge. If Australian society and media focus solely on the Indo-Pacific or US–China rivalry while ignoring transatlantic frictions, they risk missing critical insights into allied dynamics and future shifts in global security policy.

Divisions Within the EU on Russia Policy

Europe is often portrayed as a unified supporter of Ukraine, yet in reality EU member states differ significantly in their approaches to Russia, military assistance, and sanctions, revealing internal political, economic, and strategic tensions that hinder coordination.

While most EU members formally condemn Russian aggression and express support for Ukraine, substantial differences remain in policy execution. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has consistently opposed or questioned large-scale aid to Ukraine, criticized military assistance, rejected the use of frozen Russian assets, and even pursued legal challenges against EU decisions, citing violations of veto rights.

Germany, by contrast, increased military assistance during 2025–26, approving new aid packages and funding through the European Peace Facility, yet remains cautious due to its political and energy constraints. Other countries span a broad spectrum: polls show strong support in the UK, Germany, and Spain for using frozen Russian assets, while Italy displays deeper political and social divisions. These disparities highlight the absence of a unified EU consensus.

Such divisions directly undermine decision-making efficiency. At a late-2025 EU summit, leaders eventually agreed on roughly €90 billion in support for Ukraine, but Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic initially opposed elements of the package, demanding safeguards against financial repercussions. This illustrated how unanimity requirements allow one or a few states to delay or reshape collective action. Efforts by the European Commission to bypass vetoes by indefinitely freezing Russian assets advanced aid delivery but sparked legal disputes and trust issues among members.

These policy splits extend decision timelines, weaken cohesion, and project an image of internal division. Observers who assume Europe is a single, unified bloc often fail to recognize these structural tensions, leading to growing doubts about the EU’s reliability on Russia and Ukraine. Core members increasingly favor “small-group” or “two-speed” cooperation rather than waiting for unanimity among all 27 states.

Germany and the “Two-Speed Europe”

Recent EU divisions are particularly evident in Germany’s military policy debates.

One of Germany’s key initiatives has been promoting a “two-speed Europe” mechanism—often referred to as the E6—centered on Germany, France, Poland, Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. This approach seeks to bypass unanimity constraints by advancing defense cooperation and strategic decisions among core economies. It focuses on coordinated military spending, integrated defense investment, supply chain security, and critical stockpiles, while prioritizing defense in the next multiannual budget framework.

The E6 concept emphasizes “coalitions of the willing,” allowing a core group to move ahead while others join later as capacity and interest permit. German Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil stated bluntly that “now is the time for a two-speed Europe,” arguing that Europe must become stronger and that continuing as before is no longer viable. This reflects widespread frustration with slow decision-making amid escalating external threats.

However, the proposal carries risks. While it signals realism among core members, it also risks institutionalizing divisions, marginalizing non-core states, and undermining confidence in the EU framework. These tensions reflect the EU’s struggle to escape institutional paralysis while confronting the pressures of the Ukraine war, energy insecurity, and uncertainty over NATO commitments.

Selective Blindness in Australian Media

Given these ongoing developments, it is implausible that Australian media—from the ABC to 9News—are unaware of Europe’s internal fractures. Why, then, does Europe remain largely ignored?

Australian governments, think tanks, and defense circles understand EU divisions, Germany’s military hesitations, Hungary’s obstructionism, and Europe’s dependence on the US. Yet mainstream media prefer simplified narratives that audiences favor. Compared with anxieties over Trump’s actions or China’s growing power, Europe is seen as distant from Australia’s immediate security concerns, outside the Indo-Pacific, and unlikely to provide direct military support. Regions not perceived as decisive for war or peace gradually disappear from coverage.

This “informed silence” carries serious consequences.

First, the Australian public is misled. Sparse reporting on European fractures creates the illusion of a unified Western front. In reality, divisions over Russia policy, energy dependence, and defense spending are profound. Hungary’s veto power during sanctions renewals, for instance, has repeatedly shaped EU outcomes. Ignoring these realities prevents Australians from accurately understanding democratic alliances and global dynamics.

Second, neglecting Europe distorts Australia’s assessment of US foreign policy. Whether the EU can serve as a reliable backstop if the US retreats from security commitments is a crucial but underexplored question. If the US pursues more transactional or isolationist diplomacy, Australia may mistakenly assume Europe can uphold the international order. Misreading European constraints risks leaving Australia strategically unprepared during crises.

Third, the gap is even clearer when considering European migrant communities in Australia. Many European Australians retain deeper awareness of EU politics, Russian policy divisions, and energy security concerns. In contrast, much of the Australian public reduces Europe to Britain and France. When media frame global politics as a simple “democracy versus authoritarianism” binary, these communities often highlight the grey areas, creating tensions in public discourse and exposing the oversimplification of mainstream narratives.

Why Understanding Europe’s Fractures Matters

The EU is far more complex than the image of a unified front suggests. Internal divisions, two-speed cooperation, and divergent national priorities constrain its ability to act cohesively. In an increasingly unstable global environment, the EU is neither fully strong nor entirely weak; it holds both cooperative potential and structural limitations.

If Australia continues to ignore Europe’s internal realities, policymakers and the public risk overestimating allied reliability and underestimating the difficulty of collective action. The key question remains: in the face of a fragmented, ambiguous European Union, can Australia still rely on traditional allies to craft realistic foreign and security policies—or will misperception leave it reactive and vulnerable? This is a warning that Australian media and decision-makers can no longer afford to overlook.

Raymond Chow

My New Challenge

Over the past few decades, I’ve written numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics. However, last October, I decided to write a book entirely different from anything I had done before, titled Solitary but Not Isolated. I chose to publish it through crowdfunding. Readers interested in supporting this book can visit the following webpage to learn more and help make it a reality.

I attended a rooftop school in Hong Kong for primary education (a unique feature of Hong Kong in the 1960s: temporary classrooms built on top of apartment blocks in resettlement areas to accommodate children who had moved into the district). Resources were extremely limited. In sixth grade, the school principal gave me and seven other students the opportunity to post our writings on the bulletin board every two weeks for the whole school to read. This was my first experience of writing for a public audience.

In secondary school at Queen’s College, the school published the annual magazine The Yellow Dragon, the earliest and longest-running secondary school annual in Hong Kong. My writings were never published there, though my photos occasionally appeared in reports of school activities. At university, I volunteered as editor for a scholarly publication by the Science Society called Exploration, but after two or three years it was discontinued as no one wished to continue it.

During university, I studied mathematics, which required little essay writing—mostly problem-solving. After entering the field of education, I wrote numerous articles on Hong Kong education that were published in newspaper columns. Later, through curriculum development and teacher training in Hong Kong, I had the rare opportunity to write and publish mathematics textbooks spanning from Grade 1 to Form 7—something unprecedented in Hong Kong.

After moving to Australia, I served as editor of the Christian publication Living Monthly, and eventually founded Sameway magazine, which continues today. From the first issue, I wrote the opening column Words of Sameway, and over 21 years, I have written a total of 745 pieces—a record of my life.

Yet writing Solitary but Not Isolated is something I never anticipated doing since I first learned about autism decades ago. Publishing this book is closely connected to my work with Sameway. I can only say this is a new challenge given by God, a chance to take Sameway to a new stage.

Those Who Love Solitude

Solitary but Not Isolated tells the story of a person with autism. Based on her experiences, the Happy Hands Organization has developed a bilingual training program to help autistic individuals transition from school to the workplace. Launched this year, the program aims to support others in similar circumstances.

Most people with autism do not actively seek social interactions. When they do engage with strangers, they may appear difficult to connect with or communicate with, often leading to social neglect or isolation. For parents and family, this creates a lifelong burden. Even those who complete secondary or tertiary education, despite having professional knowledge, often cannot fully utilize their abilities at work because of incomplete social understanding and lack of basic communication skills. Consequently, they are frequently relegated to jobs that do not match their abilities or are assigned work requiring minimal interaction.

Western society’s understanding of autism began with the lifestyle demands of modern life, emphasizing early social engagement and learning in school. Families, having fewer children, often pay close attention to each child’s development and have higher expectations. Over the decades, understanding of autism has evolved—from viewing it as a mental illness to recognizing it as a deviation from typical personality development. Yet how society should assist their growth remains uncertain.

Decades ago, Western focus was on “treating” autism. Research into genetic, environmental, or physical causes has made limited progress. Interventions to change solitary behaviors are also limited—for example, providing speech therapy in childhood or occupational therapy for daily living skills offers only partial support. While societal acceptance and support for autistic individuals have greatly increased, parents feel that more is needed when their children enter adult life and the workforce.

In short, those inclined toward solitude still face a gap in having equal opportunities to thrive socially and professionally.

Understanding Society and the World

Many autistic individuals focus intensely on specific interests, with little experience in social relationships or current events. As adults, this often leads others to perceive them as unaware of society, or even “odd.” In workplaces, where collaboration is essential, they may face exclusion. Many end up in solitary work with minimal social interaction.

Among Chinese communities, first- or second-generation immigrants with autism often face compounded challenges due to limited knowledge of society. Parents, unfamiliar with Australian systems, cannot fully guide their children, and these high-ability individuals rarely integrate with society, limiting opportunities to demonstrate their potential.

In 2024, ABC launched The Assembly, a TV interview program where host Leigh Sales trained 15 autistic individuals to conduct interviews and produce the show. Participants significantly increased their understanding of society and the world, and their communication and social skills improved greatly.

Last year, Sameway had the opportunity to train a bilingual autistic new immigrant, successfully helping her become a magazine editor. Meanwhile, the Happy Hands Organization developed a workplace adaptation program for bilingual, high-functioning autistic individuals. Through four to six months of training, this program offers these often-overlooked individuals a chance to adapt and develop in Australia.

Thus, Sameway is not only an information platform supporting immigrant communities but also provides a development space and opportunities for those with special needs. Readers interested can contact our magazine or the Happy Hands Organization for details.

The Loneliness of Immigrants

Many immigrants arrive in Australia as adults. They often lack opportunities to understand society deeply and, due to work and life commitments, rarely have the time to engage fully with their new environment or develop close relationships with Australians. Consequently, most live within Chinese communities with similar backgrounds. Passive personalities or limited social skills often lead to intense feelings of loneliness.

Leaving their original home and social networks creates a sense of marginalization similar to that experienced by some autistic individuals. Many immigrants are willing to understand and engage with their new society but face personal limitations and a lack of proactive governmental support, leaving them unable to integrate fully into Australian life.

Chinese immigrants, in particular, may rely heavily on long-term Chinese social media and information platforms, further isolating them from the broader society. This social isolation significantly affects their participation and engagement in Australian life.

The goal of Sameway is to assist immigrants in integrating into Australia, fostering participation and engagement in society. We hope that with continued support, we can go further and achieve more.

During the Christmas and New Year period, “Sameway” relocated though only to a spot less than 100 meters across from their original office. It was a tiring task, but we have finally settled in, allowing us to take a longer break during the holiday.

However, the world still undergoes significant changes. The President of Venezuela has been forcibly taken to New York for trial, while the new leader of Venezuela is willing to govern in line with U.S. interests. The longstanding alliance between Europe and the U.S. has become history in light of the U.S. attempt to purchase Greenland. The “Board of Peace” established by Trump requests that nations place the keeping of global peace in his personal hands, but attendees at the invitation include authoritarian dictators who have initiated wars multiple times. The generation that has grown up advocating for global integration, respect for human rights, and peaceful coexistence is now at a lost and confused. Will the world revert to a chaotic state governed by the law of the jungle, where strong countries dominate weaker ones, or can humanity choose to move forward in civilization by learning mistakes from history? We truly have no sure answer.

However, it is a time where the rise of Trump and the increasing power of global far-right political forces, coupled with the internet and social media replacing traditional media as the main source of information for many people. This has led to a society overwhelmed with information and challenges in distinguishing truth from falsehood, which is equally as frightening as an era where information is blocked, preventing access to necessary knowledge.

In Australia, as a multicultural country, immigrants face significant difficulties in obtaining lifestyle information through mainstream media. I believe that to build Australia as a harmonious and cohesive society, the government must invest substantial resources to assist immigrant communities to establish high-quality and credible multicultural media, and to accelerate the integration of first-generation immigrants into society, allowing them to become a driving force in social development.

In the past year, we have strengthened the current affairs information provided on our website. In the coming year, we will focus on enhancing our information services for the Chinese community through our broadcasts and magazine publications. I hope you can support us in achieving the goal of promoting the development of the Chinese immigrant community.

Starting this year, in line with the REJOICE’s initiative for bilingual new immigrants with autism, I will be writing a brand-new column to explore this topic with the community as they navigate With the NDIS program. I hope this innovative program by the REJOICE will receive your support for promotion and development within the community.

Additionally, after three years of training aimed at encouraging seniors to use social platforms to expand their community engagement, we will take a further step this year by launching training courses to assist seniors in using artificial intelligence. Our goal is to help Chinese seniors in Australia stay up-to-date and enjoy a higher quality of life brought about by AI.

In the new year, let us work together to build a stronger local Chinese community.

Listen Now

The Impetus Behind “Thriving Kids”

Europe’s Maneuvering and Australia’s Future

Sydney Christian Author Convicted Over Child Abuse Material in Novel

Australian Coalition Reunites After Brief Split

Isaac Herzog’s Controversial Visit to Australia

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

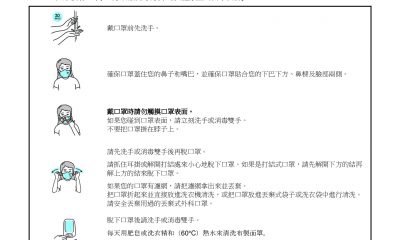

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized6 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單