Understand the World

The Trouble with Chinese National Day

Published

2 years agoon

I was born and raised in Hong Kong, and my good friend Samuel Pho was born and raised in the former South Vietnam. We have been in Australia for many years and have integrated into the Australian life, both of us believe that we are 100% Australian, and we agree that Australia can develop into a multicultural society, which is the way forward for us and our next generation. However, we have a different view of the society we grew up in. Every October, there are celebrations in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC). Before 2016, I was both invited by the Chinese Consulate and the Taiwan Office to attend the official celebrations, which I did my best to do, as both national days are, I believe, important days in Chinese history. However, after 2017, I noticed that I was only invited to attend the celebration on October 10th, which was a bit saddening.

Born and raised in Hong Kong

Hong Kong was a British colony before 1997, but the British were smart enough to realize that Hong Kong could not be governed without material support and supplies from China. Therefore, after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), on January 6, 1950, the PRC announced that it recognized the Chinese Communist regime as the ruler of mainland China, and that the two countries would soon establish normal diplomatic relations. However, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) demanded to take over the seat of the ROC in the United Nations and to receive her overseas assets. Subsequently, the Korean War broke out, and the diplomatic relations between China and Britain ceased to progress. It was not until 1971 when the Chinese Communist regime took over the seat of the ROC in the United Nations that China and Britain formally established diplomatic relations and exchanged ambassadors in 1972.

From 1949 to this time in Hong Kong, people celebrated the National Day of the People’s Republic of China on October 1 every year, and some five-star red flags were placed on the streets, but not very loudly. I knew from a very young age that because of the 1967 riots in Hong Kong supported by the Chinese Communist Party, the British Hong Kong government was on high alert for the National Day of the People’s Republic of China, and those in the community who supported the Communist Party of China were not very active in celebrating the National Day in public because of the frequent confrontations between them and people with different political views. In the community and on the streets, there were more and larger celebrations.

Portraits of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of modern China , and President Chiang Kai-shek could be seen on the streets of Hong Kong until 1972, and as a teenager, I felt that there was only one China, but two regimes coexisting at the same time, until today. However, as a resident of a British colony, I believed that whichever China or regime is in my mind, it was only my motherland, meaning that it exists in history, not in the reality of everyday life. To me, China was an imaginary historical existence, and Hong Kong people were more concerned about how they live every day. There were many Hong Kong people who were concerned about how they could help their friends and relatives in China during the Cultural Revolution, as they were having a harder time than Hong Kong people. There were also those who are waiting to reunite with their families in Taiwan, which seemed to be a paradise for the Chinese.

Teenage Dreams

After 1972, the presence of the Republic of China (ROC) faded from Hong Kong society, and the director of the Xinhua News Agency (NHK) had more say in Hong Kong issues. The British also had to think about what they wanted to do in Hong Kong. In 1984, when China and Britain signed the Joint Declaration, the people of Hong Kong were told that Hong Kong would be a part of China in 97 years’ time. The reality at the time was that most Hong Kong people were terrified, but Deng Xiaoping’s “one country, two systems” still gave some people confidence, especially those who could not leave and had no choice. To me, who was young and poor and still studying, I had no property to be “shared” with, no job to lose, and no worries. However, at the age of 16, when I read the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Engels, I could not help but be moved by their passion, and believed that communism was an epoch-making ideal for mankind.

In the 70’s, my third sister moved to Australia, and later on, more of my brothers and sisters moved to the same country. My third sister told me that I did not have to pay tuition fees to study at a university in Australia, and she hoped that I would come to Australia to study. At that time, I was studying at Queen’s College and got a scholarship to enter the University of Hong Kong. I felt that there was no reason for me to leave my hometown, cross the ocean, and go to a society with a completely different culture just for the sake of free university education, so I stayed in Hong Kong. However, I sometimes thought that being an Australian was not so bad. It’s a vast country with a lot of resources, but when I thought about the fact that I had never lived in the countryside and I didn’t have the confidence to start from scratch, and even though Australia is also headed by Queen Elizabeth, it was better to be still than to make a move, so I didn’t want to change my nationality.

What is even more interesting is that when I was in Hong Kong, I did not feel the exploitation, oppression and bullying that many people said colonialism inflicted on 95% of Hong Kong people at that time. On the contrary, I saw the Hong Kong government’s vigorous social reforms and the economic take-off of Hong Kong, as well as the great improvement in the lives of most Hong Kong people (including my family). I believe that if I left school and worked in the society, and I would have many opportunities to make more contributions to my own society, so staying in Hong Kong for development is the best way out for me. However, the contradiction between my thoughts and my real life experience made me decide to go back to China to see for myself what kind of country I wanted to identify with two years after graduating from university.

I traveled alone in China for six months, and after listening to the opinions of the people I met living in China, I made a decision about where I wanted to go. The lives of the hundreds of millions of Chinese living in China were a problem that no one could solve, but by staying in Hong Kong, I could do what I wanted for the community in which I lived. It didn’t matter whether it was a British colony, or a Republic of China that had no existence, or a China that was beginning to reform and opened up.

The most important thing was that I saw that Hong Kong people were the masters of Hong Kong, and that the Hong Kong government publicized that “Hong Kong is my home”.

China through the eyes of a Vietnamese Chinese

Talking to Samuel Pho, I often found it hard to understand why he could accept that the Chinese, who made up less than 5% of Vietnam’s population, had more than 95% of the country’s wealth and a social status so high as to be discriminatory against the Vietnamese. If this were to happen in Australia today, where less than 5% of the Chinese population discriminate against Australians here, I believe the Australians would have banned the Chinese from immigrating to Australia a long time ago.

I realized that Vietnam had been a vassal state of China for more than 2000 years, sometimes even under China’s direct control, and then became a French colony, and it was only after the Second World War that Vietnam became an independent country. It was only then that I realized that the Chinese in Vietnam had the same high status that the British had in Hong Kong when I was a child. This was due to the strong political influence of the Chinese Empire during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The Chinese in Vietnam did not have to be directly involved in the governance of Vietnam, because the Chinese in Vietnam were only a small minority of the population, but they had all the wealth of the land. Therefore, France could easily become the sovereign state of Vietnam at the end of the Qing Dynasty, because the Qing government simply gave up the rule of Vietnam voluntarily.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Chinese in Vietnam still received a Chinese language education provided by the ROC, and many of them went to Taiwan to study university education. Therefore, today, most of the Vietnamese Chinese in Australia participate in the celebrations of the National Day of the Republic of China (ROC). As a result, the Chinese government rarely invites Chinese leaders from Southeast Asia who are reluctant to give up their ties with Taiwan to attend the annual 11th National Day celebrations.

However, most of the Vietnamese Chinese in Australia today are unwilling to accept the confiscation of all their property and their expulsion to the sea of fury by the Vietcong, and therefore are not enthusiastic about China’s 11th National Day. For many Vietnamese Chinese in Australia, their love of China can only last until their generation, and the next generation of Vietnamese Chinese will all be Australians.

For them, they recognize the Double Ten National Day, but in their heart of hearts, they know that from the development of international politics, there is no telling which year in the future, this national day will disappear from their lives. However, the good news is that Australia values multiculturalism, so they can continue to celebrate the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn Festival with their community, because these are not just Chinese festivals, but festivals that are shared by all the countries in the East Asian region.

I am glad that both Samuel Pho and I call Australia home. I also believe that our next generation, and the next, and the next, and the next, will still be able to preserve these cultures without having to worry about which Chinese National Day to celebrate.

Mr. Raymond Chow

You may like

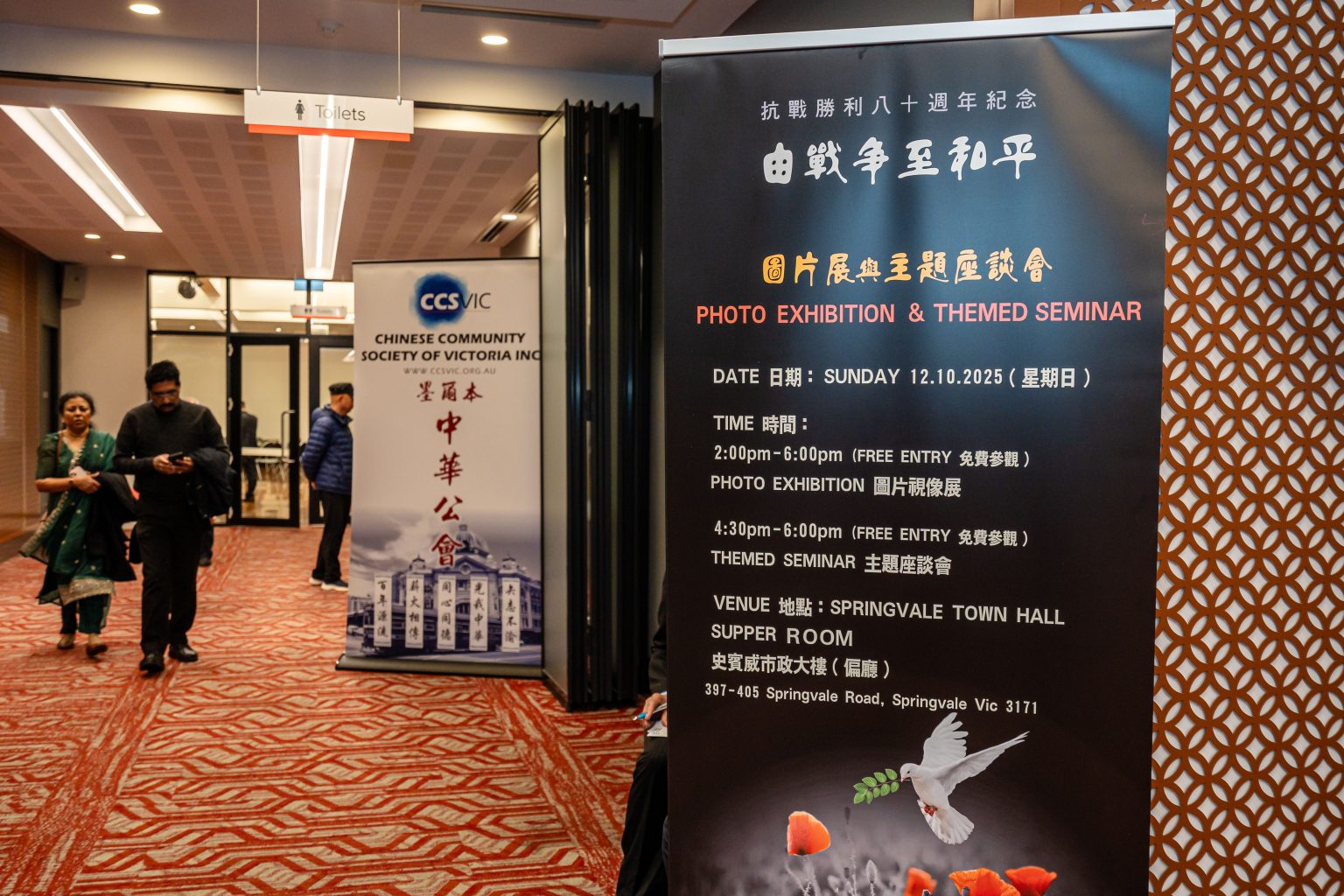

In each issue of Sameway Magazine in June, I usually write reflections on the June Fourth Massacre. The incidents that unfolded in China on that day in 1989 altered the life paths of my generation and myself. Additionally, every October, I reflect on China’s experiences over the past century. In 2011, encouraged by Taiwanese historian Dr. Gary Lin Song-huan, Sameway published a special commemorative edition every two months leading up to the centenary features publication of Republic of China. That October, we released the Centennial Special Edition exploring a century of modern Chinese history. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory over Japanese invasion of China. Not only did China hold a military parade on September 3rd, but Melbourne’s overseas Chinese community also seized this opportunity to organize various commemorative events.

While China’s victory in the War against Japan invasion is undoubtedly a cause for celebration among global Chinese communities, earlier this year, Mr. Bill Lau of the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne CYSM discussed with me: What connection can today’s generation, raised in Melbourne, possibly have with the War? What should this generation commemorate? How could the Nanking Massacre, the Siege of Shanghai, and the major battles be connected to their generation? At the time, I suggested that the Sino-Japanese War could be traced from the September 18 Incident of 1931, through the Xi’an Incident of 1936 and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937 that ignited full-scale war, ending in 1945. Doesn’t this resemble Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2013, and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict that has now stretched beyond the past three years?

Though Japan’s invasion of China unfolded on Chinese soil while the European war had yet to begin, it was entangled in the complex web of alliances and rivalries among nations worldwide. The European war erupted two years later, while the Pacific War saw U.S. entry after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. This demonstrates how the Sino-Japanese War continuously constrained the progress of the German-Japanese alliance. Reflecting on this historical period, I believe it offers profound insights into the unfolding global landscape today.

In China, everything operates under state control. The national history taught to students is entirely written by the Communist Party, and the resistance against Japan has historically received scant mention. Yet in recent years, China has vigorously promoted the narrative that the Communist Party led the anti-Japanese struggle. By stoking anti-Japanese sentiment, it has ignited Chinese nationalism, turning condemnation of Japanese militarism into official policy. On the 70th and 80th anniversaries of the War of Resistance, China held grand military parades to showcase its growing national strength. Consequently, the facts surrounding the War have garnered attention within Chinese communities worldwide.

The question of who led the resistance against Japan is actually quite straightforward to discern. When Japan began its aggression against China, the Chinese Communist Party had only recently been established and had not yet assumed governance over China. Its military strength was nowhere near what it is today. To describe the Communist Party as the main force in the resistance at that time, or as leading China’s fight against Japan, defies basic common sense. It is evident that over the past two decades, the renewed emphasis on the hatred of Japan’s invasion of China and its current threats to China is nothing more than political propaganda, not worthy of serious debate. Yet, under prolonged political indoctrination, it is indeed concerning to consider how well the younger generation of Chinese, raised in today’s China, truly grasp the facts of the Sino Japannese War.

In the commemorative events organized by various Melbourne groups this year, Mr. Bill Lau particularly emphasized that the cultural variety show should center on presenting history, allowing performers and audiences alike to revisit authentic historical events. Additionally, community education was conducted through bilingual historical photo exhibitions and the publication of a special publication. I believe this is a very sound approach. However, at one symposium I attended, certain community leaders focused solely on condemning the Communist Party for seizing mainland power through the war effort. They clearly exploited the commemoration as a platform for political posturing, which was deeply disappointing.

Undoubtedly, the eight-year War of Resistance exhausted the Nationalist forces while the Communists conducted propaganda and education campaigns, winning popular support. Furthermore, the Nationalist government’s corrupt and incompetent rule led to a deteriorating post-war economy, ultimately resulting in the transfer of rule in China and shaping today’s political landscape. It can be said that Japan’s invasion profoundly influenced contemporary Chinese politics. However, portraying this war solely as a calamity brought about by the Communist Party does not tell the whole story.

For those of us who grew up and were educated in Hong Kong or overseas Chinese communities with open access to information, commemorating the resistance against Japan should deepen our understanding of today’s global landscape. As for the next generation or younger cohorts, I firmly believe we bear the responsibility to preserve contemporary historical events through media. We must enable them, through education, to develop critical thinking skills and uncover the truth of history.

Mr. Raymond Chow

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October 2025

Features

History Written Under Control: Comparing East and West, and Resisting Twisted Narratives

Published

3 months agoon

October 23, 2025

East And West’s Different Historical Views

History helps us understand and learn from the past. Most people agree that it is important, but the way Eastern and Western countries record history can be very different. These differences can cause confusion, disagreements, or even disputes over what really happened.

With the rise of digital media, how countries tell the story of WWII can be very different. China’s role in the war is described in various ways, showing how the media can sometimes twist history with propaganda or misinformation. We hope to cite examples of how the role of China in WWII has been documented differently, in order to detail the importance of the media’s role in twisting historical events through propaganda and disinformation.

First, China and Western countries record history differently. In the West, historical documents are stored in archives, and writers can usually record events freely. In contrast, historical China relied on a chain of official historians who copied records left earlier dynasties to write about the past dynasty. These recording historians couldn’t openly record events that will criticize the then emperors (such as iron fist rulership), as doing so could put them and their families in danger or even get exterminated.

Of course, Western history isn’t perfect either. From an outsider’s point of view, people often see the same events differently, even on how a country is invaded. For example, any elderly Chinese might strongly defend China’s actions in the Sino-Japanese wars, while western scholars may consider many factors like land disputes, political conflicts, and ideology when explaining about the war.

Western countries often value knowledge and individual thinking for everyone. China, on the other hand, has a long history of centralized control over information. Even before printing technology was established, China had a unified written language and centralized monitored historians, to allow government control on how history was recorded. Japan had a central government too, but regional differences in culture and record-keeping still existed. Smaller countries like Laos relied more on local communities and oral traditions to preserve historical records. These examples show that whether a society values individualism or collectivism can greatly affect how history is written and remembered.

Because of this difference, history can easily be twisted when personal or political interests are involved. Today, traditional historians are fading into the sunset, slowly being replaced by 24/7 news media. If countries continuously presenting biased or incomplete versions of events, the public’s understanding becomes confused and biased. Governments or storytellers may ignore events that don’t fit their desired narrative, leaving important truths hidden.

China’s current education on the Sino-Japanese Wars

For example, Chinese textbooks often present the CCP as the main force leading the fighting against the Japanese, but that’s not entirely accurate. The Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek actually led the early efforts, reluctantly joining forces with the CCP after the Xi’an Coup. In fact, Japan’s invasion of China began earlier than the 1937 Lugou Bridge / Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The CCP often blames Manchukuo for allowing the Japanese army in invading Manchuria, but this reflects only part of the truth. While the Manchurians had some influence over that area, Manchuria was controlled by warlords, not the central Chinese government, that was Republic of China at that time. Puyi, the puppet leader, was influenced by advisors to took money from Japan and became a puppet. Looking at events from different perspectives shows how interpretations can be distorted. For example, one could ask: what if Chiang Kai-shek delayed action to avoid alerting the enemy? Even small changes like this can shape how we view the invasion’s seriousness.

The CCP also emphasizes that Chinese soldiers fought bravely while Western countries refused to help. Their narrative suggests that foreigners only cared about land and resources of China, but that’s only partly true. Britain did pressure the Qing dynasty to give up Hong Kong, but European countries and the USA avoided sending troops mainly for diplomatic reasons. Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, sending forces to China could have risked a more extensive war with Japan. Instead, the West provided weapons and supplies to the Nationalist government at that time. In hindsight, this situation is somewhat similar to the recent, three year-long Russian-Ukraine war.

The Tale of Australian William Donald

CCP influence has affected global perceptions, leading some Western countries to avoid independent research. Many Australians, for example, are unaware that some of their citizens had played key roles in the War in China with Japan. One notable figure is the Australian journalist William Henry Donald, who was deeply involved.

Donald started as a journalist and foreign correspondent before becoming an advisor of the Nationalist government in China. During the 1911 Revolution, he helped Dr Sun Yat-sen’s short-lived government negotiate with foreign powers, moving beyond reporting to active mediation. Initially, Donald admired Japan and even received a Japanese honour for his coverage of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). By 1915, however, he criticized Japanese imperialism and warned the West about its expansionist actions.

Donald played a crucial role during the Xi’an Coup, mediating between major Chinese leaders. His efforts helped secure Chiang Kai-shek’s release and the formation of a reluctant alliance with the CCP. Later, he disagreed with Chiang in 1940 over policy toward Germany. During the Pacific War, Donald was captured in Manila in 1942 but was freed in 1945. Afterward, his influence gradually declined.

Despite his decades-long involvement, historians have largely overlooked Donald’s contributions, whether advising Chiang, mediating coups, or supporting Dr Sun Yat-sen. His role is complex and less dramatic than headlines like “Chiang vs. Mao” or “Japan Invades”, so it is often ignored. In Australia, documentation about him is limited, with primary sources stored in China or specialized archives. Because Australian history education focuses more on colonial and ANZAC history, Donald’s contributions have faded from public awareness.

Chinese authorities rarely highlight Donald either. He was not a combat hero, and his advisory role could be politically inconvenient. The CCP tends to downplay internal compromises or foreign contributions, focusing instead on its own post-war achievements. Even in normal broadcasting, the media celebrating China’s journey post-war isn’t too different.

How CCP Centralization Affects Historical Documentation

Unlike many Western countries, which value history for education and heritage, China often emphasizes national pride over strict accuracy. This approach leaves younger generations unaware or unwilling to question historical events. The CCP has used systematic omission and withdrawal of all related records— sometimes called ‘amnesia therapy’ (失憶治療法) by scholars — to hide uncomfortable truths, like the Tiananmen Square Massacre. By controlling school curricula, the party successfully shapes collective memory, erasing or reframing events to suit its narrative.

In contrast, Western countries often debate controversial history publicly, offering multiple perspectives for critical analysis. The CCP also shapes views of other nations, like Japan, portraying it as a continued threat even though imperialism has ended. These examples show that history is rarely objective; it can be twisted to serve political goals. Recognizing these distortions is vital for developing critical thinking in future generations.

The CCP’s indoctrination is well-known but not unique in Asia. Postwar Japan focused on pacifism and democracy in textbooks, downplaying imperial aggression. South Korea and Taiwan have alternated between nationalist and democratic interpretations. Smaller countries like Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia relied on oral histories and local records, allowing communities to shape memory. These examples show that centralized versus decentralized record-keeping strongly affects how generations perceive the past, emphasizing that control over history shapes national identity.

Australia’s Involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War

The CCP’s influence on history goes beyond China. Cultural programs like Confucius Institutes promote party-aligned narratives internationally, shaping textbooks, museum exhibits, and media coverage abroad. Ignoring other perspectives, like those from Australia or Japan, can create a skewed understanding of WWII. This shows that controlling historical narratives isn’t just domestic indoctrination; it’s also a form of soft power.

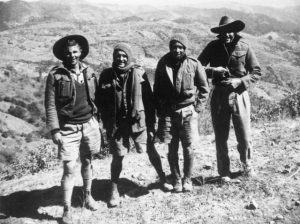

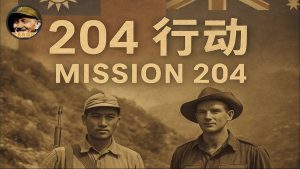

Australia has made its own mistakes in recording history. While it doesn’t claim any credit as the CCP, it has largely hidden its involvement in China through the little-known Mission 204. In 1942, around 250 Commonwealth troops, including 48 Australians from the 8th Division, were sent to aid Chiang Kai-shek. Despite logistical difficulties and tense relations with Chinese commanders, these troops carried out successful operations, including ambushes and a notable raid on Japanese barges near Poyang Lake.

Mission 204, however, was withdrawn in November 1942 due to internal politics and health issues in the unit. Later, the Chinese Nationalist Party was forced to retreat to Taiwan by the CCP. For decades, Australia largely ignored or hid this history, only resurfacing clues in 2023. While avoiding CCP politics is understandable, it’s unfair to deny the public knowledge of Australia’s wartime actions, which effectively allows the CCP to dominate the narrative.

These examples show that celebrations of China surviving the Sino-Japanese War and WWII are often shaped by political agendas and media control. This leaves the public with incomplete, biased, or deliberately obscured views. Without critical analysis or access to multiple sources, key figures, like William Henry Donald, and events can be forgotten or misrepresented.

Viewing History Through A Critical Lens

Furthermore, whether in textbooks or news reports, the same historical events can be portrayed very differently depending on who tells the story. Motivations such as national pride, political advantage, or control over public narrative all highlight the need for careful comparative study. Governments exploit each new, impressionable generation by spreading half-truths or even outright lies under the guise of patriotism and unity. When in reality, it’s about framing themselves as ‘heroes’. The longer this continues, the fewer people will question the fabricated histories imposed by those in power.

When reading history, we shouldn’t take it at face value. What gets celebrated is rarely the full story, as many crucial voices stay buried under mainstream narratives. To avoid being misled by half-truths or polished myths, readers must take proactive steps to seek balance and truth.

For example, readers can compare news sources from different cultural backgrounds. Take the case of war survival anniversaries: a Chinese state outlet might glorify its own soldiers, while a Western outlet could focus on diplomatic strategy, such as why Western powers, despite ties with the invaded nation, chose not to intervene militarily. These contrasts reveal how bias shapes every narrative.

Another approach is to encourage counterfactual thinking, which is by exploring ‘what if’ scenarios to engage with history critically. Asking questions like “What if Chiang Kai-shek had acted sooner?” or”How might events differ if textbooks included multiple perspectives?” pushes readers to think beyond surface facts. By presenting alternative viewpoints side by side, educators and media can remind younger generations that history is layered, contested, and never entirely fixed.

News Media’s Historical Responsibilities

Additionally, should news outlets depend less on governmental sources, in order to report historical events to newer generations? For instance, the CCP often promotes itself as the sole hero in the Sino-Japanese war, overlooking many other factors that contributed to Japan’s defeat. To provide a fuller picture, journalists should consult academic historians from diverse backgrounds and archives. If local reporters are unable to do so, international media should avoid over-reliance on Chinese outlets, helping to diversify perspectives. Even when governments provide data, reporters must cross-check multiple sources: comparing war casualty numbers, dates, and accounts from different national archives.

To combat biased or incomplete narratives, media organizations must embrace investigative journalism. Rather than relying solely on press releases or government celebrations, journalists should explore archives, personal accounts, and lesser-known sources. This approach can uncover overlooked contributors, hidden controversies, or forgotten stories, such as the decades-long influence of William Henry Donald in China. Without such diligence, these stories risk being lost to history.

Other than Official Historical Narratives

Historical events are rarely one-dimensional. To ensure accuracy, news outlets should present both domestic and foreign perspectives. For instance, reporting on the Sino-Japanese War should not rely solely on CCP or Chinese Nationalist sources; Japanese accounts, Western observers, and even oral histories from survivors’ descendants can provide valuable insight. By comparing these perspectives, readers gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of events and can see where bias, pride, or self-interest has shaped narratives.

History is often told through the lens of nations, prominent leaders, or major battles, leaving countless contributors invisible. Unsung figures – nurses on the frontlines, translators bridging cultural and linguistic gaps, local militias defending communities, and ordinary civilians navigating war — have all shaped outcomes without formal recognition. Grassroots organizers and community leaders often mitigated famine, displacement, or political oppression, yet their stories rarely appear in mainstream textbooks. Highlighting these individuals challenges simplified nationalist accounts and invites readers to critically examine history from multiple angles. By including personal stories, letters, diaries, and oral histories, historians and educators can provide a richer, more nuanced understanding, showing that history is not only the story of leaders but also of ordinary people whose everyday decisions ripple across generations.

Importance of Multifaceted Historical Narrations

Historical narratives are not confined to academic debate; they actively shape contemporary geopolitics and international relations. The CCP’s control over historical interpretation has profoundly affected public perception of Taiwan, the South China Sea, Hong Kong, and Japan, often framing policies as defensive or restorative to fit a particular national narrative. Textbooks emphasizing the ‘century of humiliation’ or heroic struggles against foreign powers can reinforce domestic support for assertive policies abroad.

Understanding these manipulations shows how governments leverage history to justify policy, cultivate national sentiment, and shape international perception. Media, educational programs, and cultural diplomacy can extend this influence globally, subtly guiding how other countries interpret events involving China. Recognizing these dynamics is crucial for analysts, educators, and citizens, highlighting that history is not merely a record of the past but also a tool actively deployed to influence present-day politics and international relationships.

Digital Era’s Challenges Towards History

The landscape of historical narrative has further shifted in the digital age. Social media platforms are not just spaces for connection but arenas for ideological competition. TikTok, WeChat, YouTube, and Twitter/X have become battlegrounds for competing interpretations of history. Viral clips, memes, and algorithmically promoted content often shape perceptions more strongly than formal education. Algorithms tend to favor content that evokes strong emotions – national pride, outrage, or sensationalism – reinforcing particular viewpoints while suppressing others. Unlike these fast-moving but potentially biased feeds, traditional textbooks, though limited in perspective, are curated and vetted to ensure factual consistency.

For younger generations growing up online, cultivating media literacy, critical thinking, and the ability to cross-reference multiple sources is essential. This is not only to resist propaganda but also to engage with history in its full complexity. Encouraging discussions about the origins and credibility of online content empowers students to recognize how narrative manipulation occurs in real time. It prepares them to approach information critically throughout their daily lives.

Finally, historical reporting should be more understandable to younger generations. The media can leverage multimedia tools – short videos, infographics, timelines, and interactive articles – to break down complex events. Clear, engaging formats, using layman language and visuals, can prevent oversimplification and reduce the risk that a single, potentially biased narrative dominates public understanding.

In an age of propaganda, selective memory, and curated narratives, readers must approach history critically. By seeking multiple sources, questioning official accounts, and embracing diverse perspectives, we can resist half-truths and uncover the full story. History is not just a record of the past; it is a tool for understanding the present and shaping a more informed future. If media, educators, and citizens take these steps seriously, hidden figures like William Henry Donald and many others who shaped history behind the scenes can finally receive the recognition they deserve.

Editorial : Raymond Chow, Jenny Lun

Photo: Internet

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October, 2025

“Those who use force to feign benevolence are tyrants; tyrants must have great nations. Those who practice benevolence through virtue are kings; kings need not be great—Tang ruled with seventy miles, and King Wen with a hundred miles. Those who subdue others by force do not win their hearts; their strength is insufficient. Those who subdue others through virtue win their hearts and gain their sincere submission, like the seventy disciples who submitted to Confucius!”

—Mencius: Gongsun Chou

On June 21, U.S. warplanes crossed the Atlantic and launched precision airstrikes on three key Iranian nuclear facilities—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—in an operation codenamed “Midnight Hammer,” shocking the world. Three days after the strike, the NATO summit in The Hague opened, and Europe finally approved an unprecedented plan to increase defense spending—NATO allies committed to raising defense spending to 5% of GDP over the next 10 years, far exceeding the current 2% guideline. Recently, International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Rafael Grossi stated that despite attacks on multiple Iranian nuclear facilities by the United States and Israel, Iran is likely to resume uranium enrichment “within months.” The complex consequences of the U.S. airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities remain to be assessed over time.

Consequences of the strikes remain unclear

In addition to the U.S. strikes on three Iranian nuclear facilities, Israel carried out preemptive strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, military sites, and personnel between June 13 and 24, causing further damage to Iran. Recently, Israel has been negotiating with Hamas to reach an agreement. Mediators in the Gaza Strip are in contact with Israel and Hamas, hoping that Gaza can also follow the momentum of the ceasefire between Israel and Iran. Trump publicly stated that he believes both sides may reach a ceasefire agreement within seven days.

However, Iran does not seem to have responded positively to the possibility of the United States easing its “strong” sanctions. Instead, Khamenei issued his first public statement after the war, declaring “victory over the U.S. regime.” Since the war began, Khamenei has not been seen in public. Following this statement, Trump immediately abandoned all efforts to ease sanctions and other matters. The Iranian Foreign Ministry has not yet responded to this.

Following the “Midnight Hammer” operation, Trump stated at a White House press conference that Iran’s nuclear facilities had been destroyed and that he did not believe Iran would ‘quickly’ resume nuclear weapons activities. However, International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Grossi stated that despite attacks on multiple Iranian nuclear facilities by the United States and Israel, Iran could likely begin producing enriched uranium “within months.”

After all, it remains unclear whether Iran was able to transfer part or all of its approximately 408.6 kilograms of highly enriched uranium stockpile before the attacks. This uranium is enriched to 60%, above civilian levels but still below weapons-grade. If further refined, it would be sufficient to produce more than nine nuclear bombs.

Trump insists that Iran’s nuclear program has been set back “decades.” Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif stated that the damage to the nuclear facilities is “severe,” but specific details remain unclear. What is even more concerning is that the bombing of Iran’s nuclear and military facilities may result in long-term ecological damage. Soil contamination in military conflicts is one of the most severe yet often overlooked environmental consequences of war. These harmful substances often remain in the topsoil for decades, severely damaging soil quality, including its fertility and natural regenerative capacity. The consequences of Iran’s last war already forced millions of people to migrate.

A wake-up call for China

Trump’s recent strikes against Iran not only demonstrate U.S. military hegemony in the Middle East but also highlight its role as the only global power capable of unilateral action: B-2 bombers flying thousands of miles from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to strike Iran showcase America’s global power projection capabilities. This strike reinforces the United States’ prestige as the global hegemon, reminding the international community that the United States remains the most powerful player today. If the United States can precisely strike Iran’s nuclear facilities, which are highly fortified targets, then by extension, it also has the capability to strike China’s military facilities to strengthen the protection of its allies.

China maintained diplomatic restraint after the U.S. airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities and did not take any substantive actions to support Iran. As an ally of Israel, the United States has intervened militarily in Iran using its powerful military strength; as a close partner of Iran, China can only call for de-escalation, lacking substantive leverage to avoid being drawn into the conflict. This contrast highlights China’s lack of influence in the Middle East—despite its growing economic interests in the region, it is not a major security actor, limiting its role.

The resurgence of U.S. power has undermined the Chinese political elite’s claim of “the rise of the East and the decline of the West,” as well as the appeal of China’s proposed “alternative global order.” China’s restraint and low profile in the Iran crisis reflect the limitations of its global influence, which is also why China seeks to position itself as a stabilizing force, contrasting with Trump’s “America First” policy. Although the United States deployed B-2 bombers to demonstrate its military strength, the focus was on Iran and Israel, so China will not immediately alter its Taiwan strategy unless the United States explicitly links the two regions. The “Midnight Hammer” operation at most serves as a deterrent from the United States toward China.

China seeks stability and opposes the use of military means to resolve any type of conflict or confrontation, regardless of the parties involved, and there are reasons for this. After all, over half of China’s crude oil imports depend on the Middle East, and China is the largest consumer of Iranian oil. A prolonged war would disrupt its oil supply, and an Iranian blockade of the strategically important Strait of Hormuz would have the same consequences. During this period, China’s greatest concern is avoiding the threat of “soaring oil prices” to its energy security. Only by positioning itself as a potential mediator and rational voice amid the escalating regional crisis can China indirectly safeguard its investments, trade, and business operations amid the turmoil.

Europe’s Ambiguous Shift in Attitude

European countries have sharp divisions over Israel’s actions in the Gaza war, with many European citizens strongly opposing them on humanitarian grounds. Over the past few months, Israel’s far-right government has been isolated in Europe, and Netanyahu has become the subject of an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court. Two ministers, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir, have been sanctioned by the UK, with some EU countries planning to follow suit. However, European parties generally acknowledge that Iran’s nuclear program poses an existential threat to European security.

Since the airstrikes began, the UK, France, and Germany have publicly acknowledged that Iran’s nuclear weapons pose a threat not only to Israel but also to Europe. European countries have not issued major condemnations of the airstrikes targeting Iran’s nuclear capabilities. For instance, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer called for de-escalation but mentioned the UK’s “long-standing concerns” about Iran’s nuclear program. In this context, Iran has now placed the Gaza war on the back burner. This marks a major diplomatic victory for Israel in European strategic thinking, separating the Iranian nuclear issue from the Palestinian issue and paving the way for the Netanyahu government to gain some legitimacy on the European continent.

Actions speak louder than words. At the recently concluded NATO summit, NATO member states committed to increasing defense spending to 5% of their respective GDPs. Of course, European countries are attempting to balance the currently contentious US-EU tariff and trade issues by purchasing more US defense-related products. However, this commitment clearly signals that Europe tacitly approves of the U.S. airstrikes on Iran. This is closely tied to the EU’s deep dependence on the U.S., particularly in security matters. Even if the EU disagrees with many U.S. policies, including the imposition of significant tariffs, it is likely to seek compromise with the U.S. due to a “fear of the U.S.” and cultural affinity with it.

Of course, there are still voices claiming that the U.S.’s military action constitutes an outright violation of Iran’s sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity, and sends a wrong signal to the world that disputes can be resolved through force. Although Iran does not yet possess nuclear weapons, it is clear that it has the capability to produce them. Despite Iran’s repeated denials of any intent to develop nuclear weapons, certain aspects of its nuclear program, such as uranium enrichment, have raised concerns within the international community. Actions speak louder than words. Additionally, reports indicate that Douglas McGregor, a former U.S. Department of Defense advisor and retired colonel, stated on the social media platform X that the U.S. had warned Iran two hours before bombing its nuclear facilities that an attack was imminent.

Additionally, days before Trump decided to destroy Iran’s nuclear weapons program, the Islamic Republic of Iran acknowledged that it had hundreds of sleeper cells within the United States, ready to launch attacks at any time. Under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, the intent to infiltrate sleeper cells for terrorist attacks is classified as an “armed attack,” thereby acknowledging the right to self-defense. Iran’s acknowledgment a few days before Trump’s decision to destroy its nuclear weapons program easily provided a legitimate justification for the attack. The U.S.’s decision to severely damage Iran’s nuclear facilities at this time was “a natural consequence.”

The ever-present human conflict

The U.S. airstrike on Iran compels people to reflect on whether the use of force to end war remains an option that cannot be abandoned in today’s international society. Sociologist Charles Tilly once said that war creates nations, and nations create war. In international relations, there are naturally “rules of the game” such as international treaties, the principle of sovereignty, and the supremacy of human rights; however, the frequent conflicts between different political systems and the trends of various local wars in recent years have repeatedly forced those who harbor good intentions toward humanity to recognize the importance of “power.”

The airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, coupled with the safe withdrawal of all U.S. aircraft from Iranian airspace, once again demonstrates that the United States continues to play a significant role on the international stage, particularly in the military domain, and its formidable strength is widely recognized worldwide. Additionally, this operation marks Trump taking an action he had long vowed to avoid: military intervention in a major foreign war. In this interconnected age, complete non-intervention is impossible. The issue lies in whether intervention in war is controlled by political authorities such as nations or international institutions: whether the purpose is to end the war or to assist one side or the other in the war; and through what means the aforementioned purpose is achieved.

The philosophical debate over the relationship between “purpose” and “means” has never ceased. Taking war as an example, the party that initiates the war is naturally unjust. If the opposing side then resists with force, being drawn into this forced war, their resistance is an unavoidable response, and their purpose is to stop the war. Is such resistance a necessary—or even moral—means? Contemporary conflicts and wars are endless and difficult to resolve, as if trapped in a circular argument of “the chicken or the egg,” unable to escape.

War has never completely disappeared from human history; various forms of conflict and violence have continued to occur. Any rational person opposes war. Therefore, the focus should not be on “anti-war” rhetoric, but on how to confront war—especially “war that is forced upon us.” The vast majority of people yearn for peace. The problem is that no matter how much we advocate against war or emphasize peace, there will always be those who seek to wage war for personal gain. This forces us to confront war that is forced upon us. The first priority in facing such a war is prevention. However, if prevention fails and war breaks out, the ability to resist war still lies in strength.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

Listen Now

Chasing Speed, Chasing Risk: The Safety Myth Behind Modified E-Bike Policies

Hope Amid Anti-Semitic Attacks in Australia

Examining Freedom of Speech in Hong Kong Through the Jimmy Lai Case

Victorian Farm Accused of Exploiting Migrant Workers

Middle-aged Couple Killed in Bondi Beach Shooting

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

Victorian Government Issues Historic Apology to Indigenous Peoples

Australia and U.S. Finalize Expanded U.S. Military Presence and Base Upgrade Plan

7.5-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Off Northeastern Coast of Japan

Paramount Challenges Netflix with Warner Bros Acquisition Bid

Thailand Strikes Cambodia as Border Clashes Escalate

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

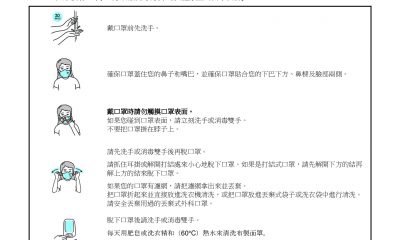

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單