Understand the World

Hong Kong’s Cantonese Conservation Activities Suppressed

Published

2 years agoon

Hong Kong’s Cantonese conservation organization, the Societas Linguistica Hongkongensis (SLHK), decided to dissolve and suspend its operations after the Hong Kong government announced last month that it had requested the removal of an essay from its 2020 essay competition that was suspected of violating Hong Kong’s National Security Law. Andrew Chan, chairman of the SLHK who is overseas, said that his family members in Hong Kong had been searched by the police. The preservation of Cantonese is not a political issue, but it is being attacked again. Hong Kong’s once stable society and rule of law are now on the verge of collapse.

An old essay triggers storm

Societas Linguistica Hongkongensis (SLHK) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) established in Hong Kong in 2013. It was started by a group of university students who saw the need to set up an organization to focus on the continued role of Cantonese in Hong Kong’s education system in light of the government’s initiative to promote the teaching and learning of Putonghua. Since its establishment, the SLHK has been committed to “safeguarding Hong Kong people’s language – Cantonese, orthographic characters, and the local culture inherited from them”. Various activities have been organized to promote the use of Cantonese in learning, and have received support from teachers and the tertiary education sector. The purpose of the essay competition is to educate the community on the importance of Cantonese as a learning language. It can be said that when the SLHK was first established, its focus was more on education and professionalism, and was not directly related to social politics. This can also be seen from the fact that the activities of the SLHK have always been funded by government departments, and that it has collaborated with language education professional organizations in various aspects.

The essay competition for the novel in question was held in June 2020, and the results were announced on 30 November. In July 2020, the Hong Kong National Security Law would come into effect. In July this year, the Hong Kong police announced a reward of HK$1 million each for eight well-known Hong Kong pro-democracy activists in exile, accusing them of allegedly violating the National Security Law, and their relatives still in Hong Kong have been repeatedly taken away by the Hong Kong police for questioning. All of a sudden, there was a great deal of panic.

At this time, the Hong Kong government has used “suppression” to raise the concern that “Hong Kong will become the second Guangzhou” and the Cantonese language may disappear. Andrew emphasized that since 2020, the community activities and organization of the SLHK have been under his sole operation. At present, the affairs of the Institute, its daily operation, social networking platform and website are all run by him alone, and he has no connection with his family members, any titled members, or any people in Hong Kong. Even so, the State Security Department has not let his family in Hong Kong off the hook – it’s a real pain in the ass to swoop in without a warrant to look for him.

The competition, which was funded by the Central and Western District Council of Hong Kong in 2020, was originally intended to produce an anthology of the 18 selected entries, but was blocked by the Home Affairs Department (HAD), which named 11 of the entries, including “Our Time”, as “involving foul language, controversial, misleading and disturbing, or affecting the harmony of the community”, and threatened to stop the funding. However, this incident was only targeted at “Our Time”. The contributor of the novel, writing under a pen name, tells the story of a man who returned to his birthplace of Hong Kong in 2050 after emigrating from the UK with his parents, only to find that most Hong Kong people no longer speak Cantonese, and that his parents’ health deteriorated due to the inhalation of too much Chinese-made tear gas. At the same time, the government changed the names of places and suppressed religious freedom in order to eliminate the colonial element. At the end of the article, the late Czech writer Milan Kundera was quoted as saying, “The struggle between man and power is the struggle between memory and forgetfulness”.

According to the National Security Bureau, the Central and Western District Office of Hong Kong had contacted Andrew Chan several times without success, and decided to take action by requesting him to take down the novels that violated the National Security Law, but Andrew Chan checked his email records and did not find any notification from the District Office requesting him to take down the articles. The suspension of SLHK is undoubtedly the latest example of the Hong Kong government’s infringement on the freedom of speech.

No room for survival once labelled

In December 2020, the SLHK submitted the first draft of an anthology of articles for the Call for Papers project. Subsequently, the District Office informed the SLHK that some of the articles submitted involved foul language, contained controversial, misleading and disturbing elements, or affected community harmony, which were not the original intent and purpose of the campaign, and had repeatedly asked the SLHK to account for how to follow up and rectify the situation through letters and emails, but the SLHK had only made a small number of revisions. The essay “Our Time” does not contain any element of “Hong Kong independence”, but is mainly an expression of feelings. Andrew Chan had called the National Security Bureau to inquire about the matter, and was told that after consulting the Department of Justice, it was said that the article had violated the National Security Law, but he was not told specifically which section of the law it violated.

Andrew Chan, a graduate of the Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU), mobilized a rally in 2018 to protest against HKBU’s mandatory Putonghua graduation examination, and was later forced to stop his internship when he was “uncovered” by the party media Global Times while studying in Guangdong. Since then, he and the SLHK have been labeled as “Hong Kong Independents” by the pro-Beijing camp in Hong Kong. Once this label is attached, it is very difficult to get rid of it, and when applying for community funding in 2020, some pro-establishment organizations labeled the SLHK as a radical and anti-China group. In today’s Hong Kong, any issue or advocacy in support of local culture can easily be labeled as “Hong Kong independence”, and Cantonese has become a target. For example, the SLHK’s advocacy against the mandatory use of Putonghua has already been categorized by the government as seditious, subversive, or secessionist behavior.

Nowadays, it seems that the opposition to the policy of replacing Cantonese with Putonghua and the promotion of cultural activities in Cantonese are all dangerous. …… is no longer a direct reference to the slogans of the “Hong Kong Independence” or the “Times Revolution” campaigns, but rather, some of the literary creations, or issues that are not directly related to Hong Kong’s social movement, can be regarded as evidence of anti-national security. One cannot help but ponder whether it is still safe to engage in literature and creative writing in Hong Kong.

“In 2014, the Hong Kong Education Bureau apologized for the statement that “Cantonese is not an official language”, but nowadays it is very difficult for the public to influence the government’s thinking, and even if we want to keep the Chinese language test, it is still unsuccessful. Even peaceful and rational advocacy is considered to be suppressed by “Hong Kong independence”. In less than a decade, the world has changed.

Cantonese is used globally

To regard Cantonese as the language of Hong Kong, and to ignore the fact that it is commonly used all over the world, is obviously a blind spot of SLHK. It is true that to the people of Hong Kong before 1997, Cantonese was the language of Hong Kong. However, if you think about it, there are many Chinese in many Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Europe, etc., who speak Cantonese. It is estimated that there are tens of millions of Cantonese speakers outside of China. The people of Hong Kong have made the “privatization” of Cantonese a matter of concern for the continuity of the Hong Kong language, and have failed to see that the continuity of Cantonese is more likely to be a language that can be preserved throughout the world.

In Australia, Cantonese is a community language recognized by all levels of governments, and is taught in community language schools in all major cities. In Victoria, there has been an initiative to establish a Cantonese as a second language course in the VCE. Australia is a country that respects multiculturalism. Regardless of whether Cantonese is considered the official language of the country in China, as long as there are people here who continue to speak this language, it is worth preserving and learning.

The Hong Kong government has the right to decide on the use of “Hong Kong dialect”. But the continued promotion of Cantonese is the right and responsibility of Cantonese speakers around the world. However, in Hong Kong today, the promotion of Cantonese has become a political agenda.

Hong Kong in the era of national security

In recent years, the survival of Cantonese in Hong Kong has been threatened, most notably by the use of Putonghua as a substitute for Cantonese in the teaching of Chinese language in many schools. Andrew says that the SLHK has contributed to the preservation of the Cantonese language over the past 10 years, but that Hong Kong is no longer a suitable place to run a similar organization. For his own safety, he will not return to Hong Kong in the near future. In the foreseeable future, the preservation of Cantonese will be regarded as a threat to national security, and Cantonese will be gradually marginalized in Hong Kong, following the footsteps of Guangzhou.

“Established in 2013 and registered as a social organization with the approval of the Hong Kong Police Force, the SLHK aims to “defend the language rights of Hong Kong people” and has organized a number of mother-tongue cultural activities in Hong Kong, defending Hong Kong people’s mother-tongue during major language crises, including the Education Bureau’s decision to classify Cantonese as a non-statutory language, the cancellation by the HKEAA of the Chinese Language Oral Examination, and the policy of “universal education for all” by the former Secretary of the HKSAR Government Ms. Linda TSAI, and has helped to expose the sale of secondary school public examination results in the “Little Red Book” recently. The “Hong Kong version of the National Security Law” has obviously created a chilling effect, as the SLHK, which is not intended to “engage in politics”, has already been recognized as illegal and has been cracked down.

In the three years since the implementation of the “Hong Kong version of the National Security Law”, Hong Kong has undergone structural changes – political instability and the suppression of news and information have had a significant impact on Hong Kong’s freedom, democracy, and even the economy and finance. The rapid changes in recent years have made it impossible for Hong Kong to return to the free and pluralistic lifestyle it used to be so proud of. Before the introduction of the Hong Kong version of the National Security Law, Hong Kong was known for its high degree of autonomy and civil liberties. Now, three years later, the society has changed drastically. Those who work as journalists have lost their media, those who draw comics have no platform, those who want to engage in politics have no right to participate in politics, those who fight for freedom for the people have lost their freedom first, and those who have made this city their home have no home to go back to.

After the implementation of the “National Security Law in Hong Kong”, the atmosphere in Hong Kong has changed drastically, and the taboo of the public has become more and more, and many people no longer express their opinions on social platforms. However, the question of “where is the red line” still remains in many people’s minds. Hong Kong is losing the checks and balances of power and democratic guardrails that it once had, and replacing them with more top-down control networks. Hong Kong residents have lost most of their freedoms, and people have to worry that any form of protest could be criminalized. What is left of a Hong Kong where everyone is at risk?

How are overseas Chinese responding?

There are Chinese people living in every country in the world, and the Cantonese-speaking areas of southern China are the main source of overseas Chinese, thus creating a situation where Cantonese is still important outside of China today. Many Chinese publications in these countries are still published in traditional Chinese characters, and Cantonese speakers still play an important role. Chinese nationals living in countries where English is the national language, and where the goal is to unite the Chinese majority, tend to accept different dialects, so both Cantonese and Putonghua are accepted. Some of the articles in this magazine use Cantonese vocabulary and expressions, which are understandable to most readers without major communication difficulties.

Some people think that it is a policy imposed by China, while others think that it is a sign that Hong Kong officials are pandering to the top. However, there is still plenty of room for individuals and communities to choose to speak, write and use Cantonese more often.

In the past, Hong Kong has played an important role in the preservation and promotion of Cantonese, but I believe that as more Hong Kong people are dispersed around the world, if “Hong Kong Language” is complemented by the Chinese communities that are already speaking Cantonese in various countries, it is very likely to add a new impetus to the promotion of Cantonese, and I believe that this is also an opportunity to promote Cantonese.

Note: As the article “Our Time” has become a global news story, the editorial team read the 2,000-word article carefully, but could not make any connection between the article and China’s national security. In order to avoid any more literal inquisition in Chinese history, we have obtained the consent of Mr. Andrew Chan, the former head of “Hong Kong Studies in Chinese”, who is believed to be the copyright holder of this article, to publish the full text of the article in this magazine, so that the public can debate on the aspects of this article that may have violated the national security law of Hong Kong. This article is published in this magazine for public debate, so that the public will know where the red line is. The publication of this article does not imply that we endorse, support or oppose the position of this article, nor do we intend to incite hatred, dissatisfaction or hostility towards any government or other community.

Article/Editorial

Photo/Internet

Our Time

(by Xiao Jia)

Editor’s Note: In this issue, we are discussing the article “Our Time”, and the editorial team is unable to understand which part of the article would make the Hong Kong National Security Agency suspect that it would cause national security problems. Since the original article has been taken down from the website, we have obtained the consent of the person in charge of the original organization to publish the original article in this magazine, hoping that Australian readers can make their own judgment on whether the content of the article will cause some national security problems. The publication of this article does not imply any endorsement, support or opposition to its position, nor is it intended to incite hatred, dissatisfaction or hostility towards any government or other community.

Kwong Chai

“No, I don’t think so! Where is Queen’s Road Central?” Kwong asked a teenage girl.

“I don’t know!” The girl said, “I don’t know!” and walked away.

Frowning, Kwong continued to walk, looking at his notebook and the crowded Central.

After a while, a woman tapped her on the shoulder and asked gently, “Is there anything I can do to help you?

This girl was very different from the first one.

“No, I’m looking for the escalator halfway up the hill.”

“Can I take you? You can call me Sze.” The girl replied with a smile.

“My name is Kwong.”

It was at this moment that Kwong got a good look at Sze. She should be in her early twenties, her skin is white and red, and her smile is so charming.

“Yes, where do you want to go, Kwong?”

“I want to go back to the places my parents used to go, one of them is the Mosque on Shelly Street.”

“I know where the mosque is! I’m on vacation today, I want to go around, why don’t we go together?”

Of course!

Many tourists wearing cheongsams take photos there.

It was just like what was written in the notebook. Kwong thought to himself.

After passing Elgin Street, there were fewer tourists. The two of them kept moving towards the mid-levels.

“After the Caine Road, along the escalator, there is a Rednalexa Terrace terrace on the right hand side, opposite to the light green mosque.” Kwong read from his notebook.

The two of them were on the Rednalexa Terrace, looking in the direction of the escalator.The mosque is at the back of the escalator.

Some people think that the name “Rednalexa Terrace” was changed from “Alexander Terrace” to “Rednalexa Terrace” because Chinese translators used to write from right to left when Hong Kong was a British colony.”It’s such a weird street name.”Kwong said excitedly.

“But some research shows that it was named in honor of Robert Alexander Young, who defended the human rights of the African people in the 19th century, and who called people living outside of Africa “Rednaxela”.”The poem adds.

There were guards at the entrance to the mosque, but they did not prevent the two of them from entering.

“In the early years of Hong Kong’s history, the British government recruited military and police officers from India, a British colony at the time, and some of them were Muslims. The mosque in Soho was the first mosque in Hong Kong,” says Kwong. Kwong was talking at great length.

Walking up the stairs, some worshippers were washing their hands by the side of the mosque, some were removing their shoes and going to the mosque, and some were teaching their children to recite sutras in the open space next to the mosque.

As stated in the front of the notebook, the center niche of the temple is the place for the Elders to recite sutras. The domed design creates a natural sound amplifier, so that the chanting can reach every corner without the use of microphones.

On the last page of the notebook, it is written: In the same community, apart from Hong Kong people, there are many different minorities who belong to this community. We need to get to know the place that belongs to us.

Kwong asked Sze, “I have other places I want to go, will you go there together?

Siu Sze

“It’s already 2050! There are still people who don’t speak Putonghua!

Sze heard a passing girl talking to herself.

It was a rare day off, so Sze planned to go to a coffee shop in Central to read books and drink coffee.

Passing by the Central Market, Sze saw a man in his late 20s, with a small beard and a matured look. The man was not a local at first sight, and was carrying a notebook and a DSLR camera. He is in the Central Market, and when he tries to walk, he retraces his steps.

There are a lot of tourists in Central, but most of them are dragging their clothes around in front of different cosmetic shops. Few of them look like the man in front of me. Driven by curiosity, I saw if there was anything I could do to help him.

The man introduced himself as Kwong, born in Hong Kong and raised in England. His mom and dad had gone away after he was born and never came back.

Sze led Kwong into the Central Market, across the footbridge to the start of the escalator.

Sze pointed to the street below the footbridge and said to Kwong, “This street is called ‘People’s Middle Road’, which was renamed 25 years ago, and the younger generation doesn’t even know its original name.

When he arrived at the Rednalexa Terrace, Kwong’s eyes were glowing and he said, “I have heard these stories for many years, and my parents have never allowed me to come to Hong Kong. My parents never wanted me to come to Hong Kong. They inhaled too much Chinese tear gas when they were born, and their health deteriorated and they died a year ago. I found this notebook among their belongings, and I have listened to their stories about Hong Kong since I was a child. They always said Hong Kong is so beautiful and special. They really love Hong Kong. I think I don’t even know why they want to leave.”

Sze did not tell Kwong that the mosque would be renamed in a few months’ time, as the government felt it was too colonial.

The two guards at the entrance of the mosque were watching them, probably hearing Kwong talk about a history they didn’t recognize. Kwong should be too excited to see them.

In 2025, the government is going to suppress freedom of religion, and all Catholic, Protestant and Muslim places of worship will be controlled. All believers will be required to join patriotic churches, and churches will be demolished if they are unwilling and disobedient. The good thing is that the mosque is a Class II historical relic, so it can be preserved first. Many people don’t know there is a mosque in SoHo because it is no longer a place for Muslims.

They are all patriotic, the children read the revised Koran and they don’t learn Arabic anymore, only Chinese. Their culture is slowly fading away and becoming extinct, just like Hong Kong 30 years ago.

Before saying goodbye to Kwong, Sze told him, “I haven’t seen locals so familiar with Hong Kong’s stories. We live in a city where every street and every building around us has its own story. If more people like your parents had remembered these stories 30 years ago, Hong Kong might not have become such a migrant city. You are more qualified than any of us to be a Hong Kong citizen.” He speaks very softly about Hong Kong people, so he is afraid that other people will hear him.

Sze gave her a book to Kwong. There is a line in the poem that I like very much.

“The struggle between people and totalitarianism is the struggle between memory and forgetfulness.”

You may like

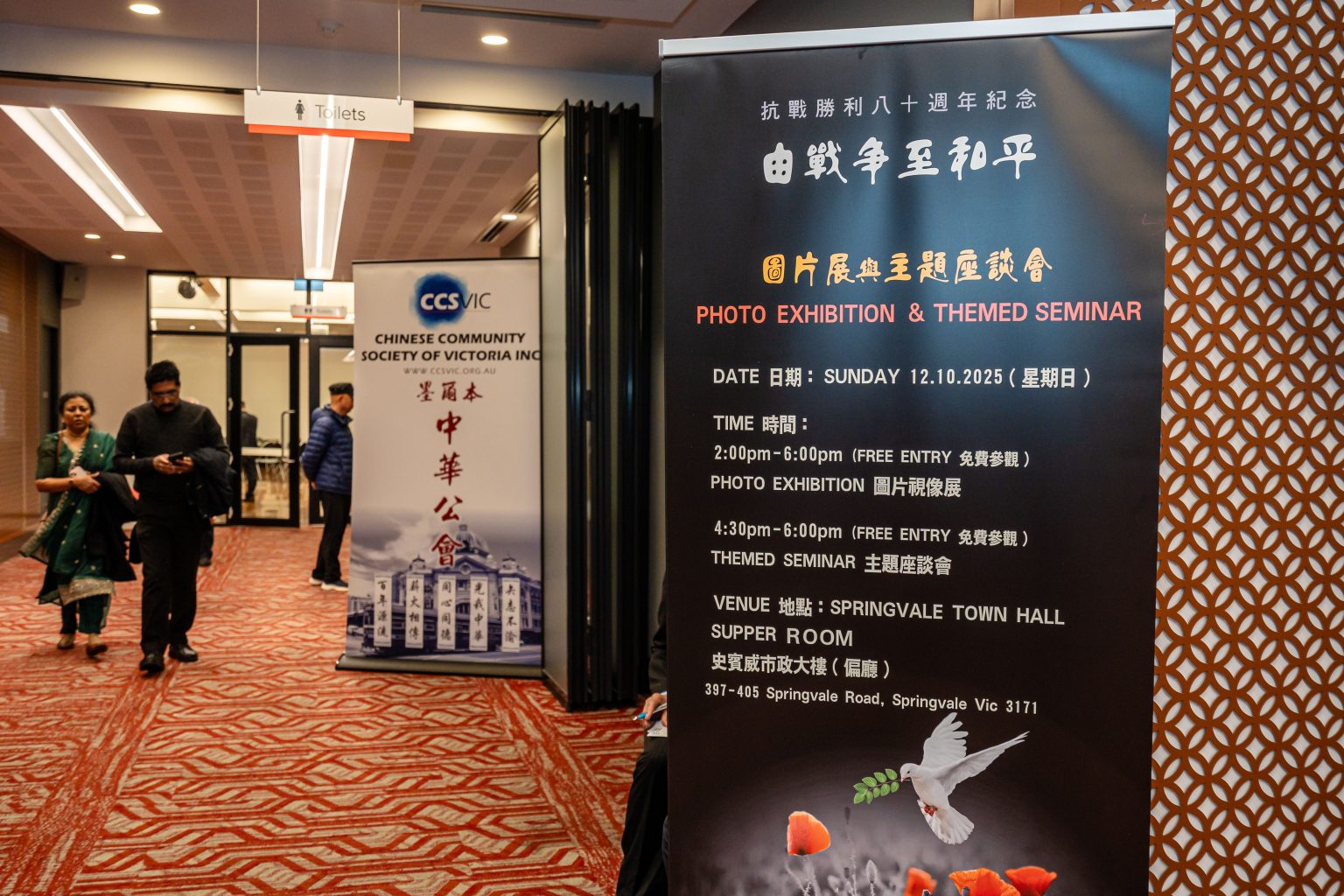

In each issue of Sameway Magazine in June, I usually write reflections on the June Fourth Massacre. The incidents that unfolded in China on that day in 1989 altered the life paths of my generation and myself. Additionally, every October, I reflect on China’s experiences over the past century. In 2011, encouraged by Taiwanese historian Dr. Gary Lin Song-huan, Sameway published a special commemorative edition every two months leading up to the centenary features publication of Republic of China. That October, we released the Centennial Special Edition exploring a century of modern Chinese history. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory over Japanese invasion of China. Not only did China hold a military parade on September 3rd, but Melbourne’s overseas Chinese community also seized this opportunity to organize various commemorative events.

While China’s victory in the War against Japan invasion is undoubtedly a cause for celebration among global Chinese communities, earlier this year, Mr. Bill Lau of the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne CYSM discussed with me: What connection can today’s generation, raised in Melbourne, possibly have with the War? What should this generation commemorate? How could the Nanking Massacre, the Siege of Shanghai, and the major battles be connected to their generation? At the time, I suggested that the Sino-Japanese War could be traced from the September 18 Incident of 1931, through the Xi’an Incident of 1936 and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937 that ignited full-scale war, ending in 1945. Doesn’t this resemble Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2013, and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict that has now stretched beyond the past three years?

Though Japan’s invasion of China unfolded on Chinese soil while the European war had yet to begin, it was entangled in the complex web of alliances and rivalries among nations worldwide. The European war erupted two years later, while the Pacific War saw U.S. entry after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. This demonstrates how the Sino-Japanese War continuously constrained the progress of the German-Japanese alliance. Reflecting on this historical period, I believe it offers profound insights into the unfolding global landscape today.

In China, everything operates under state control. The national history taught to students is entirely written by the Communist Party, and the resistance against Japan has historically received scant mention. Yet in recent years, China has vigorously promoted the narrative that the Communist Party led the anti-Japanese struggle. By stoking anti-Japanese sentiment, it has ignited Chinese nationalism, turning condemnation of Japanese militarism into official policy. On the 70th and 80th anniversaries of the War of Resistance, China held grand military parades to showcase its growing national strength. Consequently, the facts surrounding the War have garnered attention within Chinese communities worldwide.

The question of who led the resistance against Japan is actually quite straightforward to discern. When Japan began its aggression against China, the Chinese Communist Party had only recently been established and had not yet assumed governance over China. Its military strength was nowhere near what it is today. To describe the Communist Party as the main force in the resistance at that time, or as leading China’s fight against Japan, defies basic common sense. It is evident that over the past two decades, the renewed emphasis on the hatred of Japan’s invasion of China and its current threats to China is nothing more than political propaganda, not worthy of serious debate. Yet, under prolonged political indoctrination, it is indeed concerning to consider how well the younger generation of Chinese, raised in today’s China, truly grasp the facts of the Sino Japannese War.

In the commemorative events organized by various Melbourne groups this year, Mr. Bill Lau particularly emphasized that the cultural variety show should center on presenting history, allowing performers and audiences alike to revisit authentic historical events. Additionally, community education was conducted through bilingual historical photo exhibitions and the publication of a special publication. I believe this is a very sound approach. However, at one symposium I attended, certain community leaders focused solely on condemning the Communist Party for seizing mainland power through the war effort. They clearly exploited the commemoration as a platform for political posturing, which was deeply disappointing.

Undoubtedly, the eight-year War of Resistance exhausted the Nationalist forces while the Communists conducted propaganda and education campaigns, winning popular support. Furthermore, the Nationalist government’s corrupt and incompetent rule led to a deteriorating post-war economy, ultimately resulting in the transfer of rule in China and shaping today’s political landscape. It can be said that Japan’s invasion profoundly influenced contemporary Chinese politics. However, portraying this war solely as a calamity brought about by the Communist Party does not tell the whole story.

For those of us who grew up and were educated in Hong Kong or overseas Chinese communities with open access to information, commemorating the resistance against Japan should deepen our understanding of today’s global landscape. As for the next generation or younger cohorts, I firmly believe we bear the responsibility to preserve contemporary historical events through media. We must enable them, through education, to develop critical thinking skills and uncover the truth of history.

Mr. Raymond Chow

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October 2025

Features

History Written Under Control: Comparing East and West, and Resisting Twisted Narratives

Published

1 week agoon

October 23, 2025

East And West’s Different Historical Views

History helps us understand and learn from the past. Most people agree that it is important, but the way Eastern and Western countries record history can be very different. These differences can cause confusion, disagreements, or even disputes over what really happened.

With the rise of digital media, how countries tell the story of WWII can be very different. China’s role in the war is described in various ways, showing how the media can sometimes twist history with propaganda or misinformation. We hope to cite examples of how the role of China in WWII has been documented differently, in order to detail the importance of the media’s role in twisting historical events through propaganda and disinformation.

First, China and Western countries record history differently. In the West, historical documents are stored in archives, and writers can usually record events freely. In contrast, historical China relied on a chain of official historians who copied records left earlier dynasties to write about the past dynasty. These recording historians couldn’t openly record events that will criticize the then emperors (such as iron fist rulership), as doing so could put them and their families in danger or even get exterminated.

Of course, Western history isn’t perfect either. From an outsider’s point of view, people often see the same events differently, even on how a country is invaded. For example, any elderly Chinese might strongly defend China’s actions in the Sino-Japanese wars, while western scholars may consider many factors like land disputes, political conflicts, and ideology when explaining about the war.

Western countries often value knowledge and individual thinking for everyone. China, on the other hand, has a long history of centralized control over information. Even before printing technology was established, China had a unified written language and centralized monitored historians, to allow government control on how history was recorded. Japan had a central government too, but regional differences in culture and record-keeping still existed. Smaller countries like Laos relied more on local communities and oral traditions to preserve historical records. These examples show that whether a society values individualism or collectivism can greatly affect how history is written and remembered.

Because of this difference, history can easily be twisted when personal or political interests are involved. Today, traditional historians are fading into the sunset, slowly being replaced by 24/7 news media. If countries continuously presenting biased or incomplete versions of events, the public’s understanding becomes confused and biased. Governments or storytellers may ignore events that don’t fit their desired narrative, leaving important truths hidden.

China’s current education on the Sino-Japanese Wars

For example, Chinese textbooks often present the CCP as the main force leading the fighting against the Japanese, but that’s not entirely accurate. The Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek actually led the early efforts, reluctantly joining forces with the CCP after the Xi’an Coup. In fact, Japan’s invasion of China began earlier than the 1937 Lugou Bridge / Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The CCP often blames Manchukuo for allowing the Japanese army in invading Manchuria, but this reflects only part of the truth. While the Manchurians had some influence over that area, Manchuria was controlled by warlords, not the central Chinese government, that was Republic of China at that time. Puyi, the puppet leader, was influenced by advisors to took money from Japan and became a puppet. Looking at events from different perspectives shows how interpretations can be distorted. For example, one could ask: what if Chiang Kai-shek delayed action to avoid alerting the enemy? Even small changes like this can shape how we view the invasion’s seriousness.

The CCP also emphasizes that Chinese soldiers fought bravely while Western countries refused to help. Their narrative suggests that foreigners only cared about land and resources of China, but that’s only partly true. Britain did pressure the Qing dynasty to give up Hong Kong, but European countries and the USA avoided sending troops mainly for diplomatic reasons. Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, sending forces to China could have risked a more extensive war with Japan. Instead, the West provided weapons and supplies to the Nationalist government at that time. In hindsight, this situation is somewhat similar to the recent, three year-long Russian-Ukraine war.

The Tale of Australian William Donald

CCP influence has affected global perceptions, leading some Western countries to avoid independent research. Many Australians, for example, are unaware that some of their citizens had played key roles in the War in China with Japan. One notable figure is the Australian journalist William Henry Donald, who was deeply involved.

Donald started as a journalist and foreign correspondent before becoming an advisor of the Nationalist government in China. During the 1911 Revolution, he helped Dr Sun Yat-sen’s short-lived government negotiate with foreign powers, moving beyond reporting to active mediation. Initially, Donald admired Japan and even received a Japanese honour for his coverage of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). By 1915, however, he criticized Japanese imperialism and warned the West about its expansionist actions.

Donald played a crucial role during the Xi’an Coup, mediating between major Chinese leaders. His efforts helped secure Chiang Kai-shek’s release and the formation of a reluctant alliance with the CCP. Later, he disagreed with Chiang in 1940 over policy toward Germany. During the Pacific War, Donald was captured in Manila in 1942 but was freed in 1945. Afterward, his influence gradually declined.

Despite his decades-long involvement, historians have largely overlooked Donald’s contributions, whether advising Chiang, mediating coups, or supporting Dr Sun Yat-sen. His role is complex and less dramatic than headlines like “Chiang vs. Mao” or “Japan Invades”, so it is often ignored. In Australia, documentation about him is limited, with primary sources stored in China or specialized archives. Because Australian history education focuses more on colonial and ANZAC history, Donald’s contributions have faded from public awareness.

Chinese authorities rarely highlight Donald either. He was not a combat hero, and his advisory role could be politically inconvenient. The CCP tends to downplay internal compromises or foreign contributions, focusing instead on its own post-war achievements. Even in normal broadcasting, the media celebrating China’s journey post-war isn’t too different.

How CCP Centralization Affects Historical Documentation

Unlike many Western countries, which value history for education and heritage, China often emphasizes national pride over strict accuracy. This approach leaves younger generations unaware or unwilling to question historical events. The CCP has used systematic omission and withdrawal of all related records— sometimes called ‘amnesia therapy’ (失憶治療法) by scholars — to hide uncomfortable truths, like the Tiananmen Square Massacre. By controlling school curricula, the party successfully shapes collective memory, erasing or reframing events to suit its narrative.

In contrast, Western countries often debate controversial history publicly, offering multiple perspectives for critical analysis. The CCP also shapes views of other nations, like Japan, portraying it as a continued threat even though imperialism has ended. These examples show that history is rarely objective; it can be twisted to serve political goals. Recognizing these distortions is vital for developing critical thinking in future generations.

The CCP’s indoctrination is well-known but not unique in Asia. Postwar Japan focused on pacifism and democracy in textbooks, downplaying imperial aggression. South Korea and Taiwan have alternated between nationalist and democratic interpretations. Smaller countries like Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia relied on oral histories and local records, allowing communities to shape memory. These examples show that centralized versus decentralized record-keeping strongly affects how generations perceive the past, emphasizing that control over history shapes national identity.

Australia’s Involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War

The CCP’s influence on history goes beyond China. Cultural programs like Confucius Institutes promote party-aligned narratives internationally, shaping textbooks, museum exhibits, and media coverage abroad. Ignoring other perspectives, like those from Australia or Japan, can create a skewed understanding of WWII. This shows that controlling historical narratives isn’t just domestic indoctrination; it’s also a form of soft power.

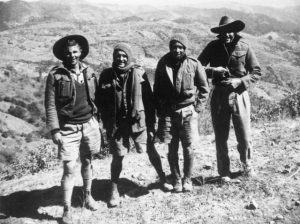

Australia has made its own mistakes in recording history. While it doesn’t claim any credit as the CCP, it has largely hidden its involvement in China through the little-known Mission 204. In 1942, around 250 Commonwealth troops, including 48 Australians from the 8th Division, were sent to aid Chiang Kai-shek. Despite logistical difficulties and tense relations with Chinese commanders, these troops carried out successful operations, including ambushes and a notable raid on Japanese barges near Poyang Lake.

Mission 204, however, was withdrawn in November 1942 due to internal politics and health issues in the unit. Later, the Chinese Nationalist Party was forced to retreat to Taiwan by the CCP. For decades, Australia largely ignored or hid this history, only resurfacing clues in 2023. While avoiding CCP politics is understandable, it’s unfair to deny the public knowledge of Australia’s wartime actions, which effectively allows the CCP to dominate the narrative.

These examples show that celebrations of China surviving the Sino-Japanese War and WWII are often shaped by political agendas and media control. This leaves the public with incomplete, biased, or deliberately obscured views. Without critical analysis or access to multiple sources, key figures, like William Henry Donald, and events can be forgotten or misrepresented.

Viewing History Through A Critical Lens

Furthermore, whether in textbooks or news reports, the same historical events can be portrayed very differently depending on who tells the story. Motivations such as national pride, political advantage, or control over public narrative all highlight the need for careful comparative study. Governments exploit each new, impressionable generation by spreading half-truths or even outright lies under the guise of patriotism and unity. When in reality, it’s about framing themselves as ‘heroes’. The longer this continues, the fewer people will question the fabricated histories imposed by those in power.

When reading history, we shouldn’t take it at face value. What gets celebrated is rarely the full story, as many crucial voices stay buried under mainstream narratives. To avoid being misled by half-truths or polished myths, readers must take proactive steps to seek balance and truth.

For example, readers can compare news sources from different cultural backgrounds. Take the case of war survival anniversaries: a Chinese state outlet might glorify its own soldiers, while a Western outlet could focus on diplomatic strategy, such as why Western powers, despite ties with the invaded nation, chose not to intervene militarily. These contrasts reveal how bias shapes every narrative.

Another approach is to encourage counterfactual thinking, which is by exploring ‘what if’ scenarios to engage with history critically. Asking questions like “What if Chiang Kai-shek had acted sooner?” or”How might events differ if textbooks included multiple perspectives?” pushes readers to think beyond surface facts. By presenting alternative viewpoints side by side, educators and media can remind younger generations that history is layered, contested, and never entirely fixed.

News Media’s Historical Responsibilities

Additionally, should news outlets depend less on governmental sources, in order to report historical events to newer generations? For instance, the CCP often promotes itself as the sole hero in the Sino-Japanese war, overlooking many other factors that contributed to Japan’s defeat. To provide a fuller picture, journalists should consult academic historians from diverse backgrounds and archives. If local reporters are unable to do so, international media should avoid over-reliance on Chinese outlets, helping to diversify perspectives. Even when governments provide data, reporters must cross-check multiple sources: comparing war casualty numbers, dates, and accounts from different national archives.

To combat biased or incomplete narratives, media organizations must embrace investigative journalism. Rather than relying solely on press releases or government celebrations, journalists should explore archives, personal accounts, and lesser-known sources. This approach can uncover overlooked contributors, hidden controversies, or forgotten stories, such as the decades-long influence of William Henry Donald in China. Without such diligence, these stories risk being lost to history.

Other than Official Historical Narratives

Historical events are rarely one-dimensional. To ensure accuracy, news outlets should present both domestic and foreign perspectives. For instance, reporting on the Sino-Japanese War should not rely solely on CCP or Chinese Nationalist sources; Japanese accounts, Western observers, and even oral histories from survivors’ descendants can provide valuable insight. By comparing these perspectives, readers gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of events and can see where bias, pride, or self-interest has shaped narratives.

History is often told through the lens of nations, prominent leaders, or major battles, leaving countless contributors invisible. Unsung figures – nurses on the frontlines, translators bridging cultural and linguistic gaps, local militias defending communities, and ordinary civilians navigating war — have all shaped outcomes without formal recognition. Grassroots organizers and community leaders often mitigated famine, displacement, or political oppression, yet their stories rarely appear in mainstream textbooks. Highlighting these individuals challenges simplified nationalist accounts and invites readers to critically examine history from multiple angles. By including personal stories, letters, diaries, and oral histories, historians and educators can provide a richer, more nuanced understanding, showing that history is not only the story of leaders but also of ordinary people whose everyday decisions ripple across generations.

Importance of Multifaceted Historical Narrations

Historical narratives are not confined to academic debate; they actively shape contemporary geopolitics and international relations. The CCP’s control over historical interpretation has profoundly affected public perception of Taiwan, the South China Sea, Hong Kong, and Japan, often framing policies as defensive or restorative to fit a particular national narrative. Textbooks emphasizing the ‘century of humiliation’ or heroic struggles against foreign powers can reinforce domestic support for assertive policies abroad.

Understanding these manipulations shows how governments leverage history to justify policy, cultivate national sentiment, and shape international perception. Media, educational programs, and cultural diplomacy can extend this influence globally, subtly guiding how other countries interpret events involving China. Recognizing these dynamics is crucial for analysts, educators, and citizens, highlighting that history is not merely a record of the past but also a tool actively deployed to influence present-day politics and international relationships.

Digital Era’s Challenges Towards History

The landscape of historical narrative has further shifted in the digital age. Social media platforms are not just spaces for connection but arenas for ideological competition. TikTok, WeChat, YouTube, and Twitter/X have become battlegrounds for competing interpretations of history. Viral clips, memes, and algorithmically promoted content often shape perceptions more strongly than formal education. Algorithms tend to favor content that evokes strong emotions – national pride, outrage, or sensationalism – reinforcing particular viewpoints while suppressing others. Unlike these fast-moving but potentially biased feeds, traditional textbooks, though limited in perspective, are curated and vetted to ensure factual consistency.

For younger generations growing up online, cultivating media literacy, critical thinking, and the ability to cross-reference multiple sources is essential. This is not only to resist propaganda but also to engage with history in its full complexity. Encouraging discussions about the origins and credibility of online content empowers students to recognize how narrative manipulation occurs in real time. It prepares them to approach information critically throughout their daily lives.

Finally, historical reporting should be more understandable to younger generations. The media can leverage multimedia tools – short videos, infographics, timelines, and interactive articles – to break down complex events. Clear, engaging formats, using layman language and visuals, can prevent oversimplification and reduce the risk that a single, potentially biased narrative dominates public understanding.

In an age of propaganda, selective memory, and curated narratives, readers must approach history critically. By seeking multiple sources, questioning official accounts, and embracing diverse perspectives, we can resist half-truths and uncover the full story. History is not just a record of the past; it is a tool for understanding the present and shaping a more informed future. If media, educators, and citizens take these steps seriously, hidden figures like William Henry Donald and many others who shaped history behind the scenes can finally receive the recognition they deserve.

Editorial : Raymond Chow, Jenny Lun

Photo: Internet

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October, 2025

“Those who use force to feign benevolence are tyrants; tyrants must have great nations. Those who practice benevolence through virtue are kings; kings need not be great—Tang ruled with seventy miles, and King Wen with a hundred miles. Those who subdue others by force do not win their hearts; their strength is insufficient. Those who subdue others through virtue win their hearts and gain their sincere submission, like the seventy disciples who submitted to Confucius!”

—Mencius: Gongsun Chou

On June 21, U.S. warplanes crossed the Atlantic and launched precision airstrikes on three key Iranian nuclear facilities—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—in an operation codenamed “Midnight Hammer,” shocking the world. Three days after the strike, the NATO summit in The Hague opened, and Europe finally approved an unprecedented plan to increase defense spending—NATO allies committed to raising defense spending to 5% of GDP over the next 10 years, far exceeding the current 2% guideline. Recently, International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Rafael Grossi stated that despite attacks on multiple Iranian nuclear facilities by the United States and Israel, Iran is likely to resume uranium enrichment “within months.” The complex consequences of the U.S. airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities remain to be assessed over time.

Consequences of the strikes remain unclear

In addition to the U.S. strikes on three Iranian nuclear facilities, Israel carried out preemptive strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, military sites, and personnel between June 13 and 24, causing further damage to Iran. Recently, Israel has been negotiating with Hamas to reach an agreement. Mediators in the Gaza Strip are in contact with Israel and Hamas, hoping that Gaza can also follow the momentum of the ceasefire between Israel and Iran. Trump publicly stated that he believes both sides may reach a ceasefire agreement within seven days.

However, Iran does not seem to have responded positively to the possibility of the United States easing its “strong” sanctions. Instead, Khamenei issued his first public statement after the war, declaring “victory over the U.S. regime.” Since the war began, Khamenei has not been seen in public. Following this statement, Trump immediately abandoned all efforts to ease sanctions and other matters. The Iranian Foreign Ministry has not yet responded to this.

Following the “Midnight Hammer” operation, Trump stated at a White House press conference that Iran’s nuclear facilities had been destroyed and that he did not believe Iran would ‘quickly’ resume nuclear weapons activities. However, International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Grossi stated that despite attacks on multiple Iranian nuclear facilities by the United States and Israel, Iran could likely begin producing enriched uranium “within months.”

After all, it remains unclear whether Iran was able to transfer part or all of its approximately 408.6 kilograms of highly enriched uranium stockpile before the attacks. This uranium is enriched to 60%, above civilian levels but still below weapons-grade. If further refined, it would be sufficient to produce more than nine nuclear bombs.

Trump insists that Iran’s nuclear program has been set back “decades.” Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif stated that the damage to the nuclear facilities is “severe,” but specific details remain unclear. What is even more concerning is that the bombing of Iran’s nuclear and military facilities may result in long-term ecological damage. Soil contamination in military conflicts is one of the most severe yet often overlooked environmental consequences of war. These harmful substances often remain in the topsoil for decades, severely damaging soil quality, including its fertility and natural regenerative capacity. The consequences of Iran’s last war already forced millions of people to migrate.

A wake-up call for China

Trump’s recent strikes against Iran not only demonstrate U.S. military hegemony in the Middle East but also highlight its role as the only global power capable of unilateral action: B-2 bombers flying thousands of miles from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to strike Iran showcase America’s global power projection capabilities. This strike reinforces the United States’ prestige as the global hegemon, reminding the international community that the United States remains the most powerful player today. If the United States can precisely strike Iran’s nuclear facilities, which are highly fortified targets, then by extension, it also has the capability to strike China’s military facilities to strengthen the protection of its allies.

China maintained diplomatic restraint after the U.S. airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities and did not take any substantive actions to support Iran. As an ally of Israel, the United States has intervened militarily in Iran using its powerful military strength; as a close partner of Iran, China can only call for de-escalation, lacking substantive leverage to avoid being drawn into the conflict. This contrast highlights China’s lack of influence in the Middle East—despite its growing economic interests in the region, it is not a major security actor, limiting its role.

The resurgence of U.S. power has undermined the Chinese political elite’s claim of “the rise of the East and the decline of the West,” as well as the appeal of China’s proposed “alternative global order.” China’s restraint and low profile in the Iran crisis reflect the limitations of its global influence, which is also why China seeks to position itself as a stabilizing force, contrasting with Trump’s “America First” policy. Although the United States deployed B-2 bombers to demonstrate its military strength, the focus was on Iran and Israel, so China will not immediately alter its Taiwan strategy unless the United States explicitly links the two regions. The “Midnight Hammer” operation at most serves as a deterrent from the United States toward China.

China seeks stability and opposes the use of military means to resolve any type of conflict or confrontation, regardless of the parties involved, and there are reasons for this. After all, over half of China’s crude oil imports depend on the Middle East, and China is the largest consumer of Iranian oil. A prolonged war would disrupt its oil supply, and an Iranian blockade of the strategically important Strait of Hormuz would have the same consequences. During this period, China’s greatest concern is avoiding the threat of “soaring oil prices” to its energy security. Only by positioning itself as a potential mediator and rational voice amid the escalating regional crisis can China indirectly safeguard its investments, trade, and business operations amid the turmoil.

Europe’s Ambiguous Shift in Attitude

European countries have sharp divisions over Israel’s actions in the Gaza war, with many European citizens strongly opposing them on humanitarian grounds. Over the past few months, Israel’s far-right government has been isolated in Europe, and Netanyahu has become the subject of an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court. Two ministers, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir, have been sanctioned by the UK, with some EU countries planning to follow suit. However, European parties generally acknowledge that Iran’s nuclear program poses an existential threat to European security.

Since the airstrikes began, the UK, France, and Germany have publicly acknowledged that Iran’s nuclear weapons pose a threat not only to Israel but also to Europe. European countries have not issued major condemnations of the airstrikes targeting Iran’s nuclear capabilities. For instance, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer called for de-escalation but mentioned the UK’s “long-standing concerns” about Iran’s nuclear program. In this context, Iran has now placed the Gaza war on the back burner. This marks a major diplomatic victory for Israel in European strategic thinking, separating the Iranian nuclear issue from the Palestinian issue and paving the way for the Netanyahu government to gain some legitimacy on the European continent.

Actions speak louder than words. At the recently concluded NATO summit, NATO member states committed to increasing defense spending to 5% of their respective GDPs. Of course, European countries are attempting to balance the currently contentious US-EU tariff and trade issues by purchasing more US defense-related products. However, this commitment clearly signals that Europe tacitly approves of the U.S. airstrikes on Iran. This is closely tied to the EU’s deep dependence on the U.S., particularly in security matters. Even if the EU disagrees with many U.S. policies, including the imposition of significant tariffs, it is likely to seek compromise with the U.S. due to a “fear of the U.S.” and cultural affinity with it.

Of course, there are still voices claiming that the U.S.’s military action constitutes an outright violation of Iran’s sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity, and sends a wrong signal to the world that disputes can be resolved through force. Although Iran does not yet possess nuclear weapons, it is clear that it has the capability to produce them. Despite Iran’s repeated denials of any intent to develop nuclear weapons, certain aspects of its nuclear program, such as uranium enrichment, have raised concerns within the international community. Actions speak louder than words. Additionally, reports indicate that Douglas McGregor, a former U.S. Department of Defense advisor and retired colonel, stated on the social media platform X that the U.S. had warned Iran two hours before bombing its nuclear facilities that an attack was imminent.

Additionally, days before Trump decided to destroy Iran’s nuclear weapons program, the Islamic Republic of Iran acknowledged that it had hundreds of sleeper cells within the United States, ready to launch attacks at any time. Under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, the intent to infiltrate sleeper cells for terrorist attacks is classified as an “armed attack,” thereby acknowledging the right to self-defense. Iran’s acknowledgment a few days before Trump’s decision to destroy its nuclear weapons program easily provided a legitimate justification for the attack. The U.S.’s decision to severely damage Iran’s nuclear facilities at this time was “a natural consequence.”

The ever-present human conflict

The U.S. airstrike on Iran compels people to reflect on whether the use of force to end war remains an option that cannot be abandoned in today’s international society. Sociologist Charles Tilly once said that war creates nations, and nations create war. In international relations, there are naturally “rules of the game” such as international treaties, the principle of sovereignty, and the supremacy of human rights; however, the frequent conflicts between different political systems and the trends of various local wars in recent years have repeatedly forced those who harbor good intentions toward humanity to recognize the importance of “power.”

The airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, coupled with the safe withdrawal of all U.S. aircraft from Iranian airspace, once again demonstrates that the United States continues to play a significant role on the international stage, particularly in the military domain, and its formidable strength is widely recognized worldwide. Additionally, this operation marks Trump taking an action he had long vowed to avoid: military intervention in a major foreign war. In this interconnected age, complete non-intervention is impossible. The issue lies in whether intervention in war is controlled by political authorities such as nations or international institutions: whether the purpose is to end the war or to assist one side or the other in the war; and through what means the aforementioned purpose is achieved.

The philosophical debate over the relationship between “purpose” and “means” has never ceased. Taking war as an example, the party that initiates the war is naturally unjust. If the opposing side then resists with force, being drawn into this forced war, their resistance is an unavoidable response, and their purpose is to stop the war. Is such resistance a necessary—or even moral—means? Contemporary conflicts and wars are endless and difficult to resolve, as if trapped in a circular argument of “the chicken or the egg,” unable to escape.

War has never completely disappeared from human history; various forms of conflict and violence have continued to occur. Any rational person opposes war. Therefore, the focus should not be on “anti-war” rhetoric, but on how to confront war—especially “war that is forced upon us.” The vast majority of people yearn for peace. The problem is that no matter how much we advocate against war or emphasize peace, there will always be those who seek to wage war for personal gain. This forces us to confront war that is forced upon us. The first priority in facing such a war is prevention. However, if prevention fails and war breaks out, the ability to resist war still lies in strength.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

Listen Now

Melbourne Woman Unable to Call 000 Highlights Telecom System Gaps

UK Military Equipment Suspected to Have Reached Accused Militia

Labor “Punishment Threat” Sparks Transparency Concerns

NDIS Reforms Leave People with Disabilities Stuck in Hospitals

Australia-US Leaders Discuss Cooperation at APEC Dinner

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

U.S. Investment Report Criticizes National Security Law, Hong Kong Government Responds Strongly

China Becomes Top Destination for Australian Tourists, But Chinese Visitor Return Slows

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Albanese Visit to UK Focuses on Domestic Reform, Not Republican Debate

Optus Faces Another “000” Outage, Singtel Bonus Sparks Controversy

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

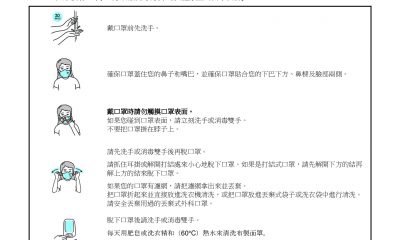

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩