Understand Australia

Rooting in Australia 2 : Should Chinese support multiculturalism?

Published

2 years agoon

What is an immigrant like?

Our readers in Australia are almost certainly first-generation immigrants, whether they come from Hong Kong, China or Southeast Asia, with different identities, experiences and backgrounds, but as immigrants living in Australia, we have encountered many of the same difficulties and similar adaptations. Australia is an immigrant-majority and immigrant-led country, and the process of social formation is different from that of other countries around the world. Therefore, the concepts of “rootedness” and “multiculturalism” are issues that we, as first-generation immigrant readers, mainly from China and Hong Kong, need to understand and explore.

Like many Chinese people, I have always had the mistaken belief that only Chinese or Chinese people will leave their homeland and migrate to the world. According to the United Nations, in 2022, there were 281 million people leaving their country of birth to emigrate to other countries. Among them, Indians were the most emigrated people, with 18 million, followed by Mexicans, with 11 million, Russians, with 10.8 million, Chinese were only the fourth largest exporter, with 10 million, and the fifth largest emigrant was the Syrian Arab Republic, with 8 million. Immigrants from these countries have different reasons and methods of immigration. Therefore, when we try to understand how immigrants live, we have to bear in mind that the problems faced by Chinese immigrants in the countries where they settle are most likely to be very different from those of other immigrant groups, and that the attitudes of each country towards new immigrants are also different.

Before we left Hong Kong to settle in Australia, I believe that most Hong Kong people have never considered the fact that hundreds of thousands of Filipino maids, Indonesian maids, Thai maids or South Asian residents in Hong Kong are also Hong Kong residents, and whether they enjoy the same rights as we do. If we think about it carefully, we will know that they are subject to great restrictions in their lives, such as not being able to change jobs at will, or having to take out insurance for medical treatment, or not having social security, etc. If we think about this as a migrant in Australia, if Australia give the same rights as we do to them in Hong Kong today, we would not have the same rights as Australians now. If the Australian government and society were to adopt the policy of Hong Kong in treating hundreds of thousands of short-term domestic helpers as they treat short-term labourers in Australia, would we find it reasonable?

I think that a country’s policy towards immigrants also reflects the values of the society, or whether the country is worth living in for a long time. Or should we stay in this country permanently?

Do immigrants need to root here?

Immigrants, or those who come to live in a country with a different social identity, will also affect their attitude towards that country. Most Asian domestic helpers in Hong Kong go back to their home countries as soon as they have earned enough money, because most of their families are still in their home countries. From the very beginning, they are temporary residents with no intention of taking root in Hong Kong, and Hong Kong society does not want them to stay here permanently. It can be said that even if they are eligible to become permanent residents of Hong Kong, they will eventually choose to “return to their roots” and reunite with their families in their home countries.

The United States absorbs the largest number of immigrants in the world, about 50 million, accounting for about one-sixth of the US population. Germany, Russia, France and the United Kingdom have also absorbed a lot of immigrants, mainly due to the rapid decline in their own populations as a result of the rapid decline in fertility rates, which has resulted in a large number of residents of their former colonial countries. The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have also absorbed a lot of immigrants, especially the United Arab Emirates, where foreign workers accounted for more than 80% of the population, due to a large demand for labour in a country with a small population and a rich country. Australia and Canada are alternative immigrant countries, implementing multicultural policies and building a fair civil society. In Australia, the total number of immigrants accounts for about 30% of the population, together with a large number of second-generation immigrants, and the multicultural population (i.e., the first generation and the second generation of immigrants with one immigrant parent) accounts for more than half of the population.

It can be said that the United States is a great blend of the world’s population, creating a unique American culture, and each individual is considered to have created the United States of America as it is today. For this reason, people who settle in the United States make it their home and seldom return to their place of origin. Western European countries such as Germany, France, Spain, and Italy are changing from European countries with rich historical traditions to countries with declining populations. The immigrants to these European countries are mostly coloured people who live in affluent societies and not many of them are willing to return to their original countries. In Russia, due to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the population of the neighbouring member states also entered Russia, and the situation was more complicated due to political changes. The UAE and Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, are made up of a small number of nationals who enjoy many rights and benefits as residents and foreign workers who do not have many opportunities for advancement. The situation is somewhat similar to that of Hong Kong’s Chinese community with a large number of short-term residents living in the country. For these short-term workers, there is no possibility for them to put down roots.

Multiculturalism in Australia

Australia is unique in that it is a vast country with Australians living alone in the Pacific Ocean, a long way from their former sovereign, the United Kingdom. The population has always been small, so in recent times the opening up of immigration quotas for immigrants from all over the world has led to the formation of a multicultural, Western, democratic society in the last 30 to 40 years. In addition, the rapid development of technology and air transport has accelerated Australia’s contact with the rest of the world and promoted globalisation. This has enabled immigrants from different nationalities to integrate into the Australian society and at the same time continue to connect with and care for their friends in their place of origin, and to continue their original life, culture and social relationships.

So, do the first generation of immigrants like multicultural Australia?

From my contact with immigrants of different ethnicities, most of them agree that Australian society has more opportunities for them to develop, and they yearn for the freedom and richness of life here, so most of them do not want to go back to their original place of origin where the living conditions are poorer. They also find that the tolerance of different cultures in Australian society gives them more room to continue their original life and culture, and therefore most of them support the development of Australia into a pluralistic society. Because these people account for a very high proportion of the Australian population, the government in power and the political parties that hope to come to power will, at least in their public policies, strongly support the development of Australia into a multicultural society.

Today, not many Australians believe that Australia should revert to a Western, British culture, but many immigrants do not want Australia to become like the Asian countries with their authoritarian rule and unfair societies. As a result, multiculturalism has become synonymous with an egalitarian society in Australia. The acceptance of multiculturalism means that everyone, regardless of where they come from, must be respected, and this is a fundamental pillar of social equality.

However, the integration of immigrants from different communities in Australia is still in its infancy. Chinese seldom participate in Jewish cultural activities, Italians do not celebrate the Lunar New Year with Chinese, Western Australians rarely participate in Chinese calligraphy and painting exhibitions, and Chinese participation in Indian celebrations of the Festival of Lights is rare. It can be said that the current consensus in Australian society is that each ethnic group has the right to preserve its own culture in the society, but it has not yet developed to the stage of promoting mutual exchanges, mutual appreciation, learning and integration.

Chinese culture plays an important role

Although Chinese people from different regions have different living habits and political views, they are still the largest multicultural ethnic group today and share the same historical and cultural roots. What is even more interesting is that up until the 1970s, many Chinese living in Southeast Asia regarded themselves as highly cultured expatriates in the region, and many of them still valued their Chinese culture when they came to Australia. Therefore, even though there are more Indian immigrants than Chinese immigrants every year, the respect and interest in Chinese culture in Australian society is still much higher than that of other ethnic groups.

China’s economic take-off in the last 30 years, and Australia’s heavy reliance on China for economic development, has led to a greater interest in learning about China and Chinese culture in the Australian community. Until China’s war-wolf diplomacy, Australians were mostly friendly to the Chinese and respected their culture. Today, despite the tense relationship between Australia and China and the fierce competition between China and the West, many Australians are still interested in Chinese culture.

Chinese immigrants to Australia, under this major theme, it is worthwhile for us to think about how to introduce the beautiful aspects of our culture to Australians, so that they can have a deeper understanding of it, as well as to promote it to immigrants of other ethnic groups. Only in this way can the Chinese have a greater influence in Australia’s future. Our strengths as immigrants are not only our capital, qualifications and skills, but also the relationships, achievements and experiences we have built up in the past, which are recognised. What sets us apart from typical Australians is our culture. While we are rooted in Australia, I believe that adding the good and beautiful parts of our traditional culture to the multiculturalism of Australia will give us the greatest opportunity for development.

Mr. Raymond Chow

You may like

Features

Cohealth Service Cutoff — Victorian Government Cannot Ignore

Published

3 days agoon

October 23, 2025

On October 16, Cohealth—one of Australia’s largest community health organizations and a non-profit medical institution—announced it would close three of its clinics. The news immediately sparked widespread public debate and criticism. The affected clinics are located in Collingwood, Fitzroy, and Kensington. The Fitzroy and Kensington clinics will cease general practitioner (GP) and consultation services this December, though they will continue providing specialized support for alcohol, drug, and domestic violence issues. The Collingwood centre is scheduled for full closure next June.

The closures will directly impact approximately 12,500 patients, resulting in 20 doctors losing their jobs and 44 nurses facing reassignment or redundancy. These clinics have long provided vital primary healthcare services to low-income individuals, the homeless, refugees, domestic violence survivors, and those with chronic illnesses, serving as an indispensable health support network within the community. However, due to insufficient funding, rising costs, and operational pressures, these services are now being forced to cease.

Nicole Bartholomeusz, CEO of Cohealth, stated that the cessation of services reflects “multiple and complex pressures, including decades of underinvestment, aging infrastructure, and funding models that don’t match actual needs or the type of care required.” She noted: “The funding we receive is only sufficient to provide standard care, but we actually serve high-need patients who often require extended appointments and comprehensive case management tailored to each individual.”

Cohealth’s current Medicare subsidy only covers physician salaries, failing to account for nurses, receptionists, and other operational costs. As wages and supply costs rise, the annual gap between clinic operating expenses and Medicare funding continues to widen.

Reforms Too Late, Support Too Little

In truth, Cohealth’s predicament did not emerge suddenly but resulted from years of accumulated challenges. Although the federal Labor government has pushed Medicare reforms in recent years to enhance the sustainability of the universal healthcare system—such as the upcoming Bulk Billing Practice Incentive Program (BBPIP) launching November 1st, which will expand Medicare coverage, encourage clinics to maintain bulk billing, and provide additional funding for facility upgrades and team expansion— This initiative aims to improve access and affordability of healthcare services, with approximately 4,800 clinics expected to benefit.

However, for Cohealth, this reform appears to have come too late. The root problem lies not solely at the federal level, but in the Victorian government’s long-standing neglect of the actual health needs within grassroots communities. The poverty, homelessness, addiction, and trauma issues plaguing local communities have long exceeded the capacity of standard clinics. Yet the Victorian government has failed to provide additional support or establish stable funding mechanisms to sustain non-for-profit healthcare providers.

Cohealth identifies two primary causes for the current crisis: First, insufficient Medicare funding from the federal government for managing complex patients; Second, the Victorian government has failed to fund upgrades for the aging facilities at the Collingwood clinic.

Cohealth has repeatedly called for government support over the years. As early as 2022, Cohealth issued a statement noting that while they supported the government’s health-focused budget, the community health model—which played a critical role during the pandemic—was once again being overlooked. At that time, Cohealth emphasized the need for comprehensive investment across the entire healthcare sector to strengthen the health system as a whole.

The clinic’s facilities have long been outdated, with roof leaks forcing appointment cancellations. Despite multiple funding applications to authorities over the years, no substantive response has been received. Infrastructure Victoria’s report highlights that government funding for community services is fragmented and inadequate. The federal government has yet to establish dedicated funding for community health infrastructure. Even though the Australian government allocated $117 billion to health and medical services for 2024-25, community health organizations received only 0.3% of Victoria’s annual health infrastructure expenditure of approximately $2 billion.

Amid chronic funding shortages and sluggish government reforms, the state government’s disregard for community needs and inaction ultimately sealed the fate of these clinics. This underscores the state government’s core responsibility in ensuring the continuity of primary healthcare services.

Who is accountable for healthcare quality and service delivery?

In fact, community healthcare systems did not originate from government initiatives but from charitable and faith-based traditions. Early hospitals were often founded by churches or charitable organizations with a simple mission: to provide basic care to the poor and vulnerable through empathy and compassion. Healthcare then embodied social conscience rather than being a product of policy or systems.

As society modernized and public health concepts emerged, governments gradually assumed responsibility, incorporating health into the realm of “public duty.” The original intent behind this shift was noble—to ensure equal access to healthcare for all. Yet the process of institutionalization and bureaucratization introduced new challenges: the original “people-centred” care became diluted by layers of administrative procedures and economic logic. Healthcare services increasingly emphasized efficiency and output, gradually losing its human warmth.

Non-profit medical institutions like Cohealth represent a continuation of this historical trajectory. They uphold the founding spirit of charitable healthcare—serving vulnerable communities while upholding the belief that everyone deserves the right to health and equal access to medical care. Yet in reality, these organizations rely on government subsidies and unstable funding sources to sustain their operations.

The contradiction lies in the fact that as societies grow wealthier, public healthcare systems should be better equipped to protect the vulnerable. Yet the opposite occurs: medical costs rise relentlessly, resource distribution grows increasingly unequal, and healthcare services become ever more commoditized. In this environment, doctors are forced to complete consultations within “six-minute appointments,” nurses and receptionists operate at breaking point, and patients slip through the cracks of the system, overlooked.

Yet when reflecting on responsibility, the question may extend beyond “Who is to blame?” to “Where should healthcare be headed?”

Should we pursue the endless quest to “cure every disease”? Or should we return to healthcare’s fundamental purpose—ensuring everyone accesses basic health protection?

When the wealthy pay more for faster, better care while the poor endure long queues, has the ideal of equality already been swallowed by market logic?

Take Hong Kong, for instance. As a low-tax society, its citizens enjoy public healthcare at minimal cost—subsidized for life simply by holding a Hong Kong ID card. However, with an aging population and healthcare staff shortages, the public system has been chronically overburdened, leading to months-long waits for emergency rooms and specialist appointments. Consequently, the affluent middle and upper classes turn to private clinics, trading money for efficiency. This creates a healthcare system that appears equitable on the surface but is fundamentally stratified: the government guarantees access to services but not equal speed or quality. In other words, everyone has the right to medical care, but whether you can get better quickly and where you receive treatment depends on how much money you have.

Canada’s public healthcare system, meanwhile, is more idealistic. All residents can access free public healthcare with a health card, free from concerns about high costs. However, long waiting times and uneven resource distribution transform “free” into another form of “cost.” When demand far exceeds supply, fairness and accessibility inevitably clash.

Moreover, should healthcare prioritize “universal access” or ‘quality’? Should governments provide “basic care” or “comprehensive coverage”?

Comparisons with China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan

From an international perspective, Australia’s public healthcare system (Medicare) differs significantly from those in mainland China and Taiwan, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages. Mainland China’s system, dominated by public hospitals, subsidizes basic care through social medical insurance (urban employee/resident insurance). However, due to its massive population and concentration of medical resources in major cities, primary community clinics often struggle to handle high-demand patients—particularly low-income groups and those with chronic conditions. This mirrors Cohealth’s current situation: “resource concentration leading to overflowing demand.”

Taiwan adopted a National Health Insurance (NHI) model emphasizing “one health insurance card, nationwide healthcare coverage,” ensuring basic medical services for all regardless of urban/rural location or income level. NHI strengthens primary care clinics through subsidies and incentives, stabilizing the family doctor system. Nevertheless, disparities in healthcare resource distribution between urban and rural areas persist, and wait times for specialist care can remain excessively long.

In contrast, Australia’s Medicare system pursues fairness and accessibility in theory. Yet in practice, non-profit primary care institutions face chronic funding shortages and aging facilities. While serving predominantly vulnerable populations, these clinics often shoulder service volumes exceeding subsidy coverage. This structural contradiction creates a significant gap between the system’s ideals and its actual service capacity, highlighting a common challenge faced by vulnerable groups under different systems: even with “systemic safeguards,” they may still be marginalized due to inadequate resource allocation.

Australia’s Core Healthcare Contradiction

Returning to Australia itself, the core issue of its healthcare system isn’t a lack of total funding, but rather structural contradictions arising from resource allocation, institutional design, and policy priorities. Medicare is primarily designed for “standard medical services” such as general consultations, basic tests, and medications. However, it does not provide corresponding subsidies for the time, labour costs, and interdisciplinary integrated care required for high-need or complex patients. This leaves vulnerable groups unable to access truly comprehensive healthcare under the existing system.

Non-profit community clinics like Cohealth exist precisely to fill this gap. They offer extended consultations, case management, mental health counselling, addiction and domestic violence support, and even multidisciplinary integrated programs—services standard GP clinics struggle to provide. However, these intensive services are not fully subsidized by Medicare. Combined with limited state investment in primary care infrastructure, clinics face chronic financial strain, ultimately forcing service reductions or partial closures.

Cohealth’s partial closures reflect a deep-seated contradiction within Australia’s healthcare system: equity and accessibility do not equate to substantive care guarantees for high-need populations. While everyone ostensibly has the right to medical care, those requiring prolonged attention and individualized management often survive only by navigating systemic gaps. The institutional design itself thus creates an “invisible inequity” for high-need patients.

Australia’s healthcare also grapples with the dilemma of balancing universal coverage and quality. On one hand, the system must ensure everyone receives at least basic treatment; on the other, complex patients require sufficient time, specialized support, and case management. In reality, however, insufficient government funding and a narrow subsidy structure make achieving both goals difficult. Doctors are forced to rush through consultations, nurses and receptionists operate at capacity, while vulnerable patients languish on waiting lists. Non-profit clinics like Cohealth strive to fill these gaps, but persistent financial pressures and policy constraints render “humanized healthcare” a luxury in practice.

In other words, the core issue with Australia’s public healthcare system isn’t merely about assigning responsibility, but whether the system can return to its founding principle: ensuring everyone accesses basic healthcare while providing high-need patients with adequate resources and compassionate support when required. Cohealth’s predicament serves as a stark warning: without structural adjustments to resource allocation by government and society, the ideal of fairness remains unattainable, and vulnerable groups will continue to be marginalized by the system.

The Victorian Government’s Indisputable Responsibility

While medical policy is set by the federal government, state governments bear responsibility for implementing it according to local realities. Cohealth’s inner-city service area has a population receiving government living subsidies that exceeds the Australian average by more than double, indicating many residents cannot afford private services. The Victorian Government’s refusal to provide financial support to institutions like Cohealth demonstrates a disregard for vulnerable communities.

A similar situation exists in elder care for multicultural communities. While federal funding supports aged care services, research indicates that non-English-speaking seniors benefit most from living in facilities that accommodate their cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Yet, emerging senior communities like the Chinese diaspora receive minimal Victorian government assistance to build suitable aged care facilities. Since 2014, Labor leader Andrews has repeatedly proposed policies to purchase four plots of land for the Chinese and Indian communities to build elderly care facilities. Yet to this day, the Victorian Department of Health continues to leave these sites vacant, failing to hand them over to community organizations to develop services. This demonstrates a dereliction of duty by government officials. This situation bears striking similarities to Cohealth Community Health Services ceasing operations today due to neglect. Should the Victorian Government conduct a thorough review of the Department of Health’s operations?

Editorial : Liz Li, Jenny Lun

Photo: Internet

Published in Sameway Magazine 24 October 2025

Features

A New Chapter for the Liberal Party: Challenges and Opportunities Under Sussan Ley’s Leadership

Published

4 months agoon

July 2, 2025

In the Australian federal election on May 3, 2025, the Liberal Party suffered a crushing defeat, marking its worst election loss in 70 years. This party, which had long dominated Australian politics, was defeated at the polls, leaving party morale at an all-time low and the future direction uncertain.

Amid this low point, Sussan Ley was elected as the new party leader, becoming the first woman to lead the Liberal Party in its history. Her appointment not only symbolizes a breakthrough in terms of generation and gender but is also seen as an opportunity to rebuild the party’s image and political positioning. Whether she can regain voter trust and lead the Liberal Party to a fresh start has become a focal point of public attention.

Last Wednesday, she delivered her first major speech since taking office at the National Press Club. From her words, demeanor, and policies, it is becoming clear that she aims to shape the Liberal Party into a more open, more willing to listen, and more representative of diverse voices.

From grassroots to politics

Sussan Ley was born in 1961 and spent her childhood in Nigeria, the Middle East, and the UK before immigrating to Australia with her parents during her teenage years. Her professional background is diverse, having worked as a pilot, air traffic controller, farm cook, and tax officer. These experiences have given her a deep understanding of grassroots life and policy operations. As a result, she is not as distant as traditional political elites but is closer to ordinary people. She is not a typical politician but has entered the political arena through her own efforts and learning.

In the early stages of her career, she worked while pursuing further education, obtaining qualifications in accounting and taxation. She then joined the Australian Taxation Office, gradually gaining an understanding of policy and public sector operations. These early experiences have enabled her to better understand the realities of ordinary Australians’ lives compared to most politicians who come from party systems, and to establish a practical and people-friendly image.

She also pursued a master’s degree at Charles Sturt University and briefly worked in academia and the field of agricultural policy. This diverse background enables her to excel in parliamentary discussions on rural and regional policies and to build long-term trust with her constituents.

After being elected to the House of Representatives in 2001, she held key positions in the health, education, and environment sectors and served as deputy party leader in 2022. Following her election as party leader after the 2025 federal election, her ascension signifies that the Liberal Party is contemplating how to redefine its values to align with the times. Ley did not rise to power through party factional maneuvering but rather through stable public support and a cross-factional image that earned her the trust of party members, making her a choice to stabilize morale in times of crisis.

It is worth noting that in 2016, she sparked controversy by purchasing a property during a business trip and claiming reimbursement of travelling expenses. Although she did not break the law, she resigned from ministerial position in 2017. The incident shook her reputation for integrity and became a challenge in her political career. However, she retained her parliamentary seat and returned to the policy core, gradually rebuilding her political influence and laying the groundwork for her eventual leadership role.

A leadership style and philosophy distinct from Dutton’s

Although Sussan Ley has only been in office for a very short time, the leadership style she has displayed so far is markedly different from that of her predecessor, Peter Dutton. During his tenure, Dutton was known for his hardline conservative stance, advocating for cracking down on immigration, reducing the size of the federal civil service, and proposing controversial policies such as expanding nuclear energy investment and significantly downsizing the public sector. He also faced criticism for his frequent public gaffes and inconsistent policy positions, further damaging the Liberal Party’s image.

In contrast to Dutton’s authoritarian style and tendency to exclude internal party discussions, Sussan Ley has adopted a markedly different leadership approach. Since taking office, she has emphasized collective participation and party consensus, striving to return the Liberal Party to its traditional “team decision-making” approach. For example, on the highly controversial energy and climate policy, Ley led the establishment of a task force, inviting several shadow cabinet members and backbench MPs from different factions to participate, coordinating the Liberal and National Parties’ positions on “net-zero emissions.” The task force, led by opposition energy spokesperson Dan Tehan, included members such as the shadow treasurer and the head of resources and environmental affairs, reporting directly to Ley and National Party leader David Littleproud, and jointly developing a new direction that balances stable, affordable energy supply with carbon reduction responsibilities. Such a collaborative mechanism not only helps mend internal rifts within the coalition but also demonstrates her willingness to return policy discussions to institutional procedures and collective participation, rather than a one-person dictatorial style.

Sussan Ley and Dutton also hold markedly different positions on the “land acknowledgment” ritual. Dutton has criticized the ritual for being abused and avoided it multiple times during the election campaign; in contrast, Ley proactively performed the acknowledgment in her first major speech after taking office, emphasizing that it holds significant meaning at appropriate times and should not be reduced to a mere formality or completely excluded, demonstrating a more pragmatic and respectful attitude toward multiculturalism.

Sussan Ley has also demonstrated a more open and inclusive leadership style since taking office. In her speech, she emphasized that the Liberal Party must respect and reflect the diversity and vitality of modern Australian society. “This society is composed of people from all over the world, including families raising children in the suburbs, young people striving to develop their careers, renting while pursuing homeownership, and elderly individuals with rich experience who care about the nation’s future.” She also mentioned that professionals, small businesses, volunteers, entrepreneurs, and the working class should all be valued and recognized. Her attitude shows that she values and is willing to listen to the ideas of different groups, respecting the contributions of every Australian.

Sussan Ley has also actively engaged in dialogue with various sectors of society, particularly focusing on reconnecting with young voters who were lost in the previous election. She was interviewed by The Daily Aus on June 15. *The Daily Aus* is one of Australia’s most influential online media outlets, targeting young readers with over 620,000 Instagram followers, and Dutton had previously refused to be interviewed by the media outlet. During the interview, Ley discussed student loan policies (HECS), how young mothers balance family and work, and climate change—issues of concern to young voters. She acknowledged that these are important and urgent challenges, not only critical for young people but also closely tied to the broader Australian society. She emphasized that all political parties should take young people’s voices seriously.

Additionally, she pointed out that for Australians today, the cost of living and rental pressures are the most pressing livelihood issues. Through these concrete actions, Sussan Ley is attempting to convey to the public that the Liberal Party is striving to be more in tune with the general public and to make up for past mistakes in failing to truly understand and represent young people and grassroots voters during elections.

Key policy issues: women, children, and defense

Sussan Ley also clearly articulated the policy issues she prioritizes in this public speech.

Her policy proposals are closely tied to the current international landscape. In the face of escalating conflicts and geopolitical instability, she emphasized that Australia must confront reality and address security challenges head-on. She criticized the Labor government for being insufficiently proactive in defense preparedness, urging Australia to increase its defense budget to 3% of GDP, accelerate the development of military capabilities such as drones, missiles, and space technology, and address the shortage of personnel in the Australian Defense Force. At the same time, she also addressed Australia’s stance toward China, stating that bilateral respect and good relations should be maintained, but that provocative actions such as Chinese military ships patrolling around Australia must be met with a firm response. She emphasized that Australia must confront the competitive and threatening world it now faces and deepen cooperation with its allies.

As a female leader, she also turned her attention to long-neglected social issues. She emphasized that domestic violence and gender-based violence are a national disgrace. Drawing on her personal experiences, she spoke out on behalf of women, expressing understanding for the fear, control, and self-blame they feel, and promising to incorporate this empathy into future decision-making. She also called for the government to allocate more resources and encourage male groups to participate in reforms, arguing that men’s health policies are also part of women’s safety.

Additionally, she has highlighted the challenges children face in the digital age, criticizing tech giants for profiting from addictive designs. She has urged the government to stand with parents to prevent harm from internet addiction, misinformation, and AI abuse. She has specifically pointed out the growing harm deepfakes pose to women.

Internal Reform Challenges

However, Sussan Ley’s reform efforts will face challenges. The Liberal Party remains deeply influenced by the conservative values of the “Robert Menzies era,” with many senior party members holding conservative views on gender equality, climate change, and immigration policies, creating a significant gap with modern voters. The party’s culture has long favored maintaining the existing power structure and traditional values, lacking proactive willingness for institutional reform and ignoring the current trend where voters prioritize social justice, the environment, and inclusivity. This misjudgment has made the Liberal Party’s policies appear outdated, leading to a significant loss of votes from young people and minority groups.

The Liberal Party’s recent election defeats have been particularly severe in some areas, especially in suburban regions that were once long-standing strongholds for the party but are now experiencing voter defections. This indicates a growing disconnect between the party and local grassroots communities. If Leah wants to reverse this trend, she must rebuild substantive relationships with local communities. Sussan Ley has indicated that she will reallocate resources to regional branches to enhance their autonomy and training capabilities, but this will require significant long-term investment.

Moreover, an increasing number of Australian voters, particularly those from multicultural communities and immigrant backgrounds, no longer identify with the “white middle-class” as the mainstream culture. Instead, they expect policies that reflect their diverse identities and experiences. In this context, the Liberal Party’s long-standing political image is gradually losing its influence. The core values of “hard work, family, and entrepreneurial spirit” that were once emphasized must be reinterpreted in today’s diverse immigrant society; otherwise, they will become hollow rhetoric disconnected from the lives of most voters. If Sussan Ley is to successfully lead the Liberal Party through this transformative period, she must actively integrate diverse ethnicities, genders, faiths, and social experiences into mainstream values to create a more inclusive political image.

In recent federal elections, the Liberal Party has clearly lost the support of the majority of multicultural immigrants. To regain their support, the party cannot simply focus on policies to manage immigration numbers but must instead develop concrete plans to assist immigrants in effectively participating in and contributing to multicultural Australia within a short timeframe. In this regard, both the Liberal Party and the Labor Party have yet to propose any concrete solutions. The previous government proposed the Multicultural Framework Review, but no concrete implementation plans have been put forward. If Sussan Ley’s Liberal Party can take the lead in proposing specific policy implementations within this framework, it may have the opportunity to rebuild the Liberal Party’s recognition within the immigrant community.

However, Sussan Ley also faces pressure from hawkish factions within her party, who emphasize “free markets,” “spending cuts,” and “national defense and security first.” This makes any open stance toward immigration risk being viewed as compromise or even betrayal within the party. Ley needs time and strategy to persuade these conservative voices to understand that if the party does not adjust its mindset, it will be left behind by the times.

Additionally, the Liberal Party has long faced criticism over Indigenous affairs, particularly for its conservative stance during the “Indigenous Voice” referendum, which has left the party lacking an effective platform for dialogue with Indigenous communities. While Sussan Ley has not publicly supported this reform, she has stated that the party should establish more substantive partnerships with communities. How she handles this issue in the future will also serve as a key indicator of her leadership’s inclusivity.

Opportunity in Crisis

Sussan Ley adopts a calm and rational communication style, avoiding inflammatory language and shunning media sensationalism. She advocates that the Liberal Party must become more inclusive, truly reflecting the voices of Australia’s diverse modern society. She emphasizes teamwork, thoughtful policy-making, and gradual reform.

In the current context of a diversifying electorate and shifting values, the Liberal Party will struggle to rebuild social trust if it cannot fully shed its past ideological and cultural baggage. As the first female party leader, Sussan Ley’s emergence undoubtedly symbolizes a new beginning for the Liberal Party, but to truly turn the tide, institutional outcomes and policy actions are needed. Whether she can transform her personal experiences into organizational reform momentum will determine the trajectory of her political career and the future of the Liberal Party.

She must actively promote cultural transformation within the party, combining incentive mechanisms with policy support to create space for diverse political participants to thrive. Additionally, addressing global climate issues, digital economic transformation, social inequality, and Indigenous justice requires the Liberal Party to propose more forward-thinking and inclusive policy solutions.

This challenge is not only a test of Sussan Lee’s personal leadership but also a rigorous test of whether the Liberal Party can transform itself into a modern political party.

Article/Editorial Department, Sameway Magazine

Photo/Internet

Features

Monocultural, Multicultural, and Intercultural Society

Published

5 months agoon

May 23, 2025

Liberal Party fails to recognize multiculturalism

The Liberal Party suffered a massive defeat in the federal election, with Leader Dutton losing the Dickson seat he held for 24 years. The Liberal Party elected Sussan Ley as leader and Ted O’Brien as deputy. Ted O’Brien, who has lived in Taiwan for many years to learn Chinese and managed his family’s business in China, is one of the few Liberal leaders who is familiar with Chinese culture. After his election, Ted said that the Liberal Party needed to renew itself and propose policies that would meet the needs of modern Australia, including rethinking its policies on youth, women, migrants and the environment, or else the Liberal Party would be unable to build a relationship with the Australian electorate and its survival would be in doubt.

The Labor Party, which aims to reform the society, regards migrants, especially those from poor countries, as a disadvantaged group. Therefore, the Labor Party’s policies occasionally help migrants to adapt, and most of the leaders of the Labor Party have a more open attitude towards supporting migrants. The Liberal Party has always emphasized on small government and fairness of the system, and its leadership has little experience with immigrant communities, and basically has little understanding of the difficulties migrants encounter in adapting and integrating into the society, and therefore is not enthusiastic in supporting migrants in its policies.

Over the past two decades, Australia has absorbed more than 200,000 immigrants every year. These new migrants have found that the Labor Party has more policies that benefit migrants, and this has been reflected in the fact that migrants have been more supportive of the Labor Party’s governing in the past elections. In this year’s federal election, the Liberal Party’s Dutton blamed migrants for Australia’s economic pressures and housing shortages, and demanded a drastic reduction in the number of migrants, and senior Senator Jane Hume called Chinese Australians “spies”, which made many migrants detest the Liberal Party. If the Liberal Party still fails to recognize and respond to the reality that Australia has become a multicultural society, we can foresee that the Liberal Party is likely to disappear from the Australian political scene.

Lack of multicultural experience among societal and political leaders

Before the abolition of the White Australia Policy in the 1970s, Australia was a white society, and even the Aboriginal people, who were the owners of the land, were denied and ignored. The Chinese used to make up more than 15% of Australia’s population during the Gold Rush era, but under the White Australia Policy, less than 1% of Chinese Australians remained in the 1970s. In terms of today’s universal values, the Australian government had implemented a “non-violent” policy of genocide. In fact, the Stolen Generation’s policy of handing over Aboriginal babies to white people for upbringing and education was similar. The Racial Discrimination Act of the 1970s officially ended this phase of Australia’s history, but it did not mean that Australia immediately entered a multicultural society.

Australians born before the 1990s grew up with very little contact with people of other ethnicities in their communities and lives, so racial discrimination was rampant at that time. Nowadays, most of the Australian leaders in their 40s and 50s were born in the 1980s or before. Although they accept the diversity of the Australian society today, they have never had much personal experiences with multicultural communities or migrants, and therefore seldom consider things from the perspective of a multicultural society in their policy implementation or management. For example, many managers of mainstream organizations or enterprises deeply understand that they need to enter the multicultural community in order to continue their current market or organizational goals, but they do not know how to intertct with hese communities. In Australian society, the Australian Football League (AFL) have demonstrated a determination and experience to become multicultural, as many of the AFL’s past leaders have come from multicultural backgrounds.

Similar scenarios are reflected in politics and social management, that is, when the government implements a policy, it often fails to get a response from the whole society. For example, the NDIS, which was legislated in 2013, still has less than 9% of participants from multicultural backgrounds, which is less than 40% of the original expectation. Obviously, a policy that aims to benefit people with disabilities across the country has failed to reach out to ethnic minority communities, and has resulted in many cases of abuse and misuse. It is totally unacceptable but little complaints has been made by neither mainstream Australians nor ethnic communities. Other example is services to help families troubled by gambling, which have not been used by many migrants for a long time. For many years, the organizations concerned thought that the problem was that migrants were reluctant to use their counseling services, but the truth is that these services are provided according to the Western individualistic medical model, rather than seeing gambling as a social problem that brings difficulties to the family members, let alone dealing with the problem by promoting it to the multicultural community. During the Covid pandemic, the Victorian government’s publicity of anti-epidemic measures neglected the role of multicultural media, which initially led to a situation where the infection and death rates of overseas-born people were twice as high as those of local-born people in the.early days.

Diversity in Australian Society

The Australian Bureau of Statistics recently announced that the proportion of overseas-born Australians in the population has increased to 31.5%, in response to the large number of migrants to Australia over the last 20 years. Until the early 1990s, the proportion of foreign-born people was not as high as this, and most of these people came from the United Kingdom, which was close to their cultural background, so the Australian society was not pluralistic, and it could be said that Australia was a monocultural British society at that time. At the time of the founding of the Liberal Party, Robert Menzies was confronted with such a monocultural society. Nowadays, Australia is the most multicultural society in the world. Obviously, the design and implementation of policies must take this factor into consideration.

The Labor Party’s support for multiculturalism basically allows immigrants to continue to retain their native customs, festivals and celebrations, and to tolerate each other in order to maintain respect and peace among communities. Such a society does not mean that there is communication or integration between communities. In fact, a society with no communication or integration will easily be segregated nto competing and opposing groups. It is not easy to maintain harmony and cohesion in such a society.

Last year, the Labor Party released the Multicultural Framework Review report, which was the Australian government’s first attempt to explore what kind of multicultural society Australia could become. The Commonwealth Government has so far indicated that it is also willing to provide funding support to take forward the report’s recommendations to further the realization of the framework. The report’s emphasis on the creation of a multicultural society in Australia, beginning with the recognition that Australian society started from Aboriginals, rather than solely a colonial society created by the British, is a progressive perspective in which migrants of different cultures are welcomed and accepted as part of the Australian society and culture. This means that Australia should not be a society divided by different cultural communities, but rather a modern Australia that integrates and embraces cultures from different places.

Integration into Intercultural

In order to build an integrated and inclusive society, the government has a responsibility to help migrants from all sides of the world, especially those from authoritarian societies, to experience Australian values that are different from their own, including freedom, equality, the rule of law, and human rights. Of course, migrants from non-English speaking backgrounds need to learn English and try to engage with the wider community, rather than being isolated in a culturally homogeneous migrant community.

For young migrants, this is not too difficult. Through the work environment, through life contacts, through community involvement, we see that the new generation is integrating without great difficulty. But for first generation immigrants, it is the government’s responsibility to create opportunities for them to gain exposure and experience in integration. This does not mean that the government is giving resources to migrants as a form of welfare, but rather as an investment by the community in migrants to integrate them into Australian society in the short term, so that they can contribute to Australian society as soon as possible. Such a policy would bring positive returns to the community, and would enable the migration program to maximize the social contribution of the elite settling in Australia.

Another group that has been neglected for a long time is those who were born and raised in the mainstream society. The government should also provide opportunities for them to develop through exposure to multiculturalism. For example, many traditional churches in Australia have been unable to absorb multicultural Christians and have eventually shrunk or even closed down. This is the result of not being able to keep up with the societal changes.

The unwritten expectation of Australian society has always been that newcomers will become mainstream Australians. I believe this is impossible. The challenge for Australia today is for all Australians, immigrants and native Australians (including Aboriginal Australians), to transform and integrate into modern Australians.

Mr. Raymond Chow

Listen Now

October – History

History Written Under Control: Comparing East and West, and Resisting Twisted Narratives

Cohealth Service Cutoff — Victorian Government Cannot Ignore

Anthony Albanese Meets Trump to Discuss Minerals, Defense, and Trade

Louvre Jewelry Heist Steals Historic Treasures

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

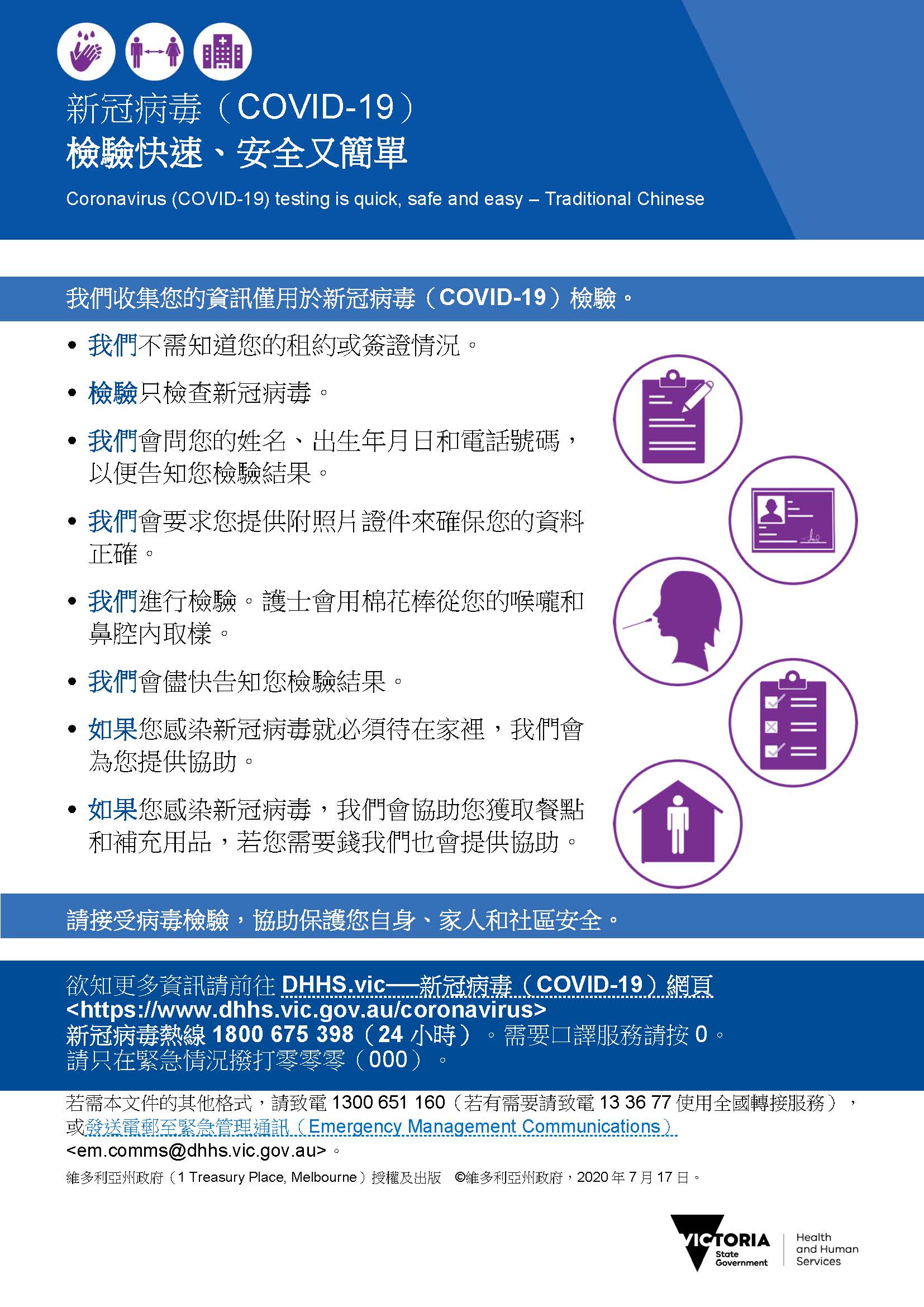

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

U.S. Investment Report Criticizes National Security Law, Hong Kong Government Responds Strongly

China Becomes Top Destination for Australian Tourists, But Chinese Visitor Return Slows

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Albanese Visit to UK Focuses on Domestic Reform, Not Republican Debate

Optus Faces Another “000” Outage, Singtel Bonus Sparks Controversy

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

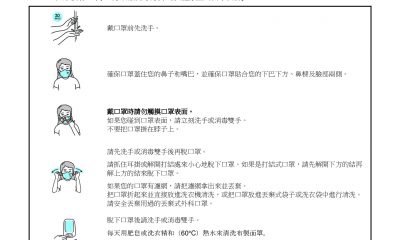

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩