Features

Traditional Media Plays an Important Role

Published

1 year agoon

Article/Blessing CALD Editorial;Photo/Internet

14 mins audio

The proportion of multicultural immigrants in Australia has increased from about 20% to 51.5% over the past 30 years. Little systematic research has been done on their roots in Australia, because the change has been so rapid and so large that the government has not understood the situation before it has had a significant impact on the community.

Until the early 1980s, immigrants to Australia were predominantly English-speaking British and non-English-speaking European immigrants with a close Christian culture. Non-English speaking immigrants who came to Australia and learned to speak English could easily integrate into the community as there was not much difference in their living habits. However, from the mid-1980s onwards, Asian non-native English-speaking immigrants became the majority, and the Australian society became more diverse. Multicultural media played an important role in the integration of these immigrants into Australia.

Only large groups of immigrants have newspapers and magazines in their own language, and most minority groups use community radio to broadcast in their own language. In every major city, the Australian government has a government-run SBS and a ethnic language radio station staffed by community volunteers. In Melbourne, 3ZZZ Ethnic Radio broadcasts in over 60 languages every week. With the increase of immigrants, there are other community radio stations, which provide minority radio stations with lesser utilized time. Today, there are more than 700 programs of ethnic language broadcasting in cities and towns across Australia every week.

SBS broadcasting began in Australia in the 1970s, and ethnic radio and television became an important part of Australian society, leading to the integration of immigrants into the community to this day. Research has shown that, to this day, these traditional media outlets are the primary means by which ethnic Australians learn about life in Australia, rather than the internet platforms that people think of.

Many people think that the internet, social media platforms and mobile smartphone technology have changed the way we access information today, and that this is the way of the new media, but this is not the case. If we think about how we change the way we think about things, we will realize that traditional media still plays an important role. For multicultural immigrants, especially Chinese immigrants, we are even more influenced by the Chinese media in Australia.

Chinese rarely use English media

Migrants other than Chinese, most of whom are Indians, are forced to use English for work or life, so English becomes a common language in their lives. As a result, many immigrants, especially young ones, use at least a little English as a language of communication after living in Australia for a period of time, and obtain information about Australia through English, unlike Chinese immigrants. Due to the large number of Chinese immigrants and their wealth, it is easy for them to establish a Chinese-dominated economic circle, and at the same time build up a lot of supportive communities. Therefore, most of the Chinese people are able to use Chinese as a language of life as they wish, and there is not much motivation for them to learn English.

Young immigrants, many of whom are professionals or have more contact with the mainstream society at work, also use basic English for communication, but not many of them are able to make speeches in English. These people can use English to access information and news in their daily lives, but at home, when they communicate with their family members or take a break from work, they mostly use Chinese, and of course, some of them use English in between. It can be said that using Chinese media is a more comfortable choice for them.

It is true that there is a lot of information in Chinese on the Internet today, which can be used by anyone in a free information society. Chinese people from different regions can actually continue to use the Chinese media that they are accustomed to using in their place of origin to communicate with their friends. Therefore, the use of Chinese language information on the Internet is primarily for social purposes, rather than for information about life in Australia. It can be said that prolonged use of online media makes it difficult for people to participate in Australian life. However, Chinese people who have been living in Australia for a long time will use high quality Chinese information sources if they are available.

Chinese-translated social media platforms are heavily used

Many Chinese social media platforms have translated many mainstream social media messages into Chinese to meet the needs of this community. For new immigrants over 50 or 60 years old, it is difficult for them to learn English, so they are happy to use these Chinese platforms.

It is in this context that the SBS Chinese TV and radio stations in Australia, whether in Cantonese or Chinese, have developed into reliable news sources, which is precisely why the Australian government is willing to invest a lot of resources in SBS. However, since SBS is funded by the Australian government, it naturally adopts the values of the mainstream Australian society and is oriented towards providing news, but cannot provide much entertainment information. However, due to the prevalence of the Internet, Chinese people can access Chinese entertainment programs anywhere on public platforms, so the quality of life of immigrants is not too restricted.

Secondly, there are many social media platforms that provide news and information in Chinese, and many people feel that they provide a lot of information in Chinese. Yes, but WeChat, which is the most widely used social media platform in China, is known to be a strictly regulated and managed system. It can be said that any information that can be disseminated must be tolerated by the Chinese government, and because of this, most WeChat users have a much lower opinion of the truthfulness and accuracy of the information that is circulated.

Moreover, the WeChat platform has also been influenced by the “navy”, which crowds out the real information with false information, and thus often misleads people, and their perception of things can be easily manipulated. Therefore, many people do not want to believe in the information spread on WeChat, and it is not easy to influence the thinking and values of Chinese immigrants. However, these platforms can be like a stratosphere of like-minded people, making it difficult for a person to accept new things and things he or she is not familiar with, and therefore not easy for a person to change his or her mind about things. It can be argued that the use of WeChat is an effective tool for the Chinese government to continue to control the thoughts and contacts of Chinese people coming to the country.

Lack of politically neutral Chinese media in the community

Due to the high cost of running a media outlet, most Chinese information services using social media platforms now hold on to their readers with low-quality translated news (many of which are translated and edited by machines in China). However, since online platforms are regulated by the Chinese government, the information obtained from these platforms only reflects certain viewpoints, so it can be said that the audience is not able to get comprehensive information.

However, after using these platforms for a long period of time, many people have come to believe that what they read is correct, and that they can’t distinguish between true and false information because they don’t have access to Australian society.

I remember in the 2018 Victorian election, the Leader of the Opposition, Matthew Guy, proposed that maintaining law and order in the home should be a key part of his platform, as it was something the Liberal Party had heard from Chinese immigrants that they valued. However, these platforms were not recognized by the general public. In the mainstream society, people simply do not think that law and order is a very important issue. In this election, the Liberal Party received even less support than in the previous one, and Matthew Guy stepped down in disgrace. Do you still remember that in WeChat, there are at least hundreds of WeChat groups organized by region to support the cooperation among Chinese people to maintain the safety of their home life? Doesn’t this show that Chinese people really believe that home safety is a big issue?

In fact, many people have pointed out that this kind of thinking is just a reaction to the insecurity of Chinese immigrants who have recently moved from living in high-rise urbanized buildings to bungalows in Australia, and due to the large distance between families, it does not really reflect that the law and order situation in Melbourne is poor or unsafe. Because everyone is talking about it, it is mistakenly assumed that this is the case, or that it is a common belief shared by the rest of the community. That’s because we’ve mistakenly taken people’s social conversations as accurate information about our society.

I remember in the same-sex marriage referendum, some people analyzed the Chinese WeChat platforms and found that a high percentage of people were against same-sex marriage, but the results of the referendum showed that the majority of Chinese people were in favor of same-sex marriage. This shows that the supporters are reluctant to express their views to their friends, while the opponents are more courageous to express their views, which creates misunderstanding in the community. Therefore, it is a mistake to take the messages sent by social media platforms as public opinion, news, or social consensus.

Traditional Chinese media in the Chinese community, especially the print media, is limited by the Chinese government’s huge foreign propaganda funding, and most of them are pro-China and full of political propaganda, which makes it difficult for independent media to survive as they try to maintain their neutrality and hope that their readers will understand and integrate into Australian society. The situation has only improved since 2016, when China abandoned its traditional media outreach, and instead monitored WeChat to influence overseas Chinese. However, it is believed that these independent media outlets still need more support from the community and mainstream society in order to survive and help the Chinese to plant their roots in Australia.

You may like

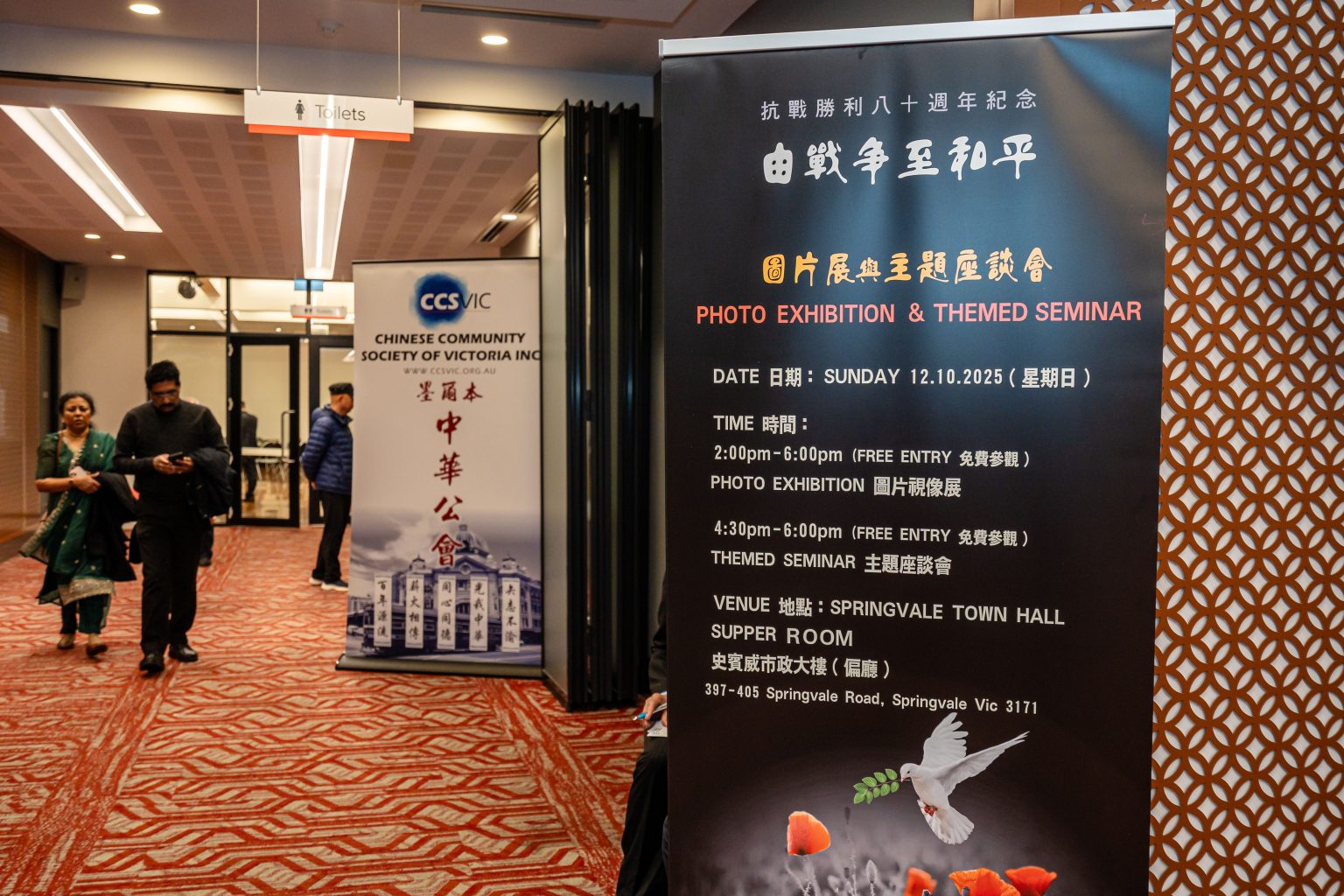

In each issue of Sameway Magazine in June, I usually write reflections on the June Fourth Massacre. The incidents that unfolded in China on that day in 1989 altered the life paths of my generation and myself. Additionally, every October, I reflect on China’s experiences over the past century. In 2011, encouraged by Taiwanese historian Dr. Gary Lin Song-huan, Sameway published a special commemorative edition every two months leading up to the centenary features publication of Republic of China. That October, we released the Centennial Special Edition exploring a century of modern Chinese history. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory over Japanese invasion of China. Not only did China hold a military parade on September 3rd, but Melbourne’s overseas Chinese community also seized this opportunity to organize various commemorative events.

While China’s victory in the War against Japan invasion is undoubtedly a cause for celebration among global Chinese communities, earlier this year, Mr. Bill Lau of the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne CYSM discussed with me: What connection can today’s generation, raised in Melbourne, possibly have with the War? What should this generation commemorate? How could the Nanking Massacre, the Siege of Shanghai, and the major battles be connected to their generation? At the time, I suggested that the Sino-Japanese War could be traced from the September 18 Incident of 1931, through the Xi’an Incident of 1936 and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937 that ignited full-scale war, ending in 1945. Doesn’t this resemble Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2013, and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict that has now stretched beyond the past three years?

Though Japan’s invasion of China unfolded on Chinese soil while the European war had yet to begin, it was entangled in the complex web of alliances and rivalries among nations worldwide. The European war erupted two years later, while the Pacific War saw U.S. entry after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. This demonstrates how the Sino-Japanese War continuously constrained the progress of the German-Japanese alliance. Reflecting on this historical period, I believe it offers profound insights into the unfolding global landscape today.

In China, everything operates under state control. The national history taught to students is entirely written by the Communist Party, and the resistance against Japan has historically received scant mention. Yet in recent years, China has vigorously promoted the narrative that the Communist Party led the anti-Japanese struggle. By stoking anti-Japanese sentiment, it has ignited Chinese nationalism, turning condemnation of Japanese militarism into official policy. On the 70th and 80th anniversaries of the War of Resistance, China held grand military parades to showcase its growing national strength. Consequently, the facts surrounding the War have garnered attention within Chinese communities worldwide.

The question of who led the resistance against Japan is actually quite straightforward to discern. When Japan began its aggression against China, the Chinese Communist Party had only recently been established and had not yet assumed governance over China. Its military strength was nowhere near what it is today. To describe the Communist Party as the main force in the resistance at that time, or as leading China’s fight against Japan, defies basic common sense. It is evident that over the past two decades, the renewed emphasis on the hatred of Japan’s invasion of China and its current threats to China is nothing more than political propaganda, not worthy of serious debate. Yet, under prolonged political indoctrination, it is indeed concerning to consider how well the younger generation of Chinese, raised in today’s China, truly grasp the facts of the Sino Japannese War.

In the commemorative events organized by various Melbourne groups this year, Mr. Bill Lau particularly emphasized that the cultural variety show should center on presenting history, allowing performers and audiences alike to revisit authentic historical events. Additionally, community education was conducted through bilingual historical photo exhibitions and the publication of a special publication. I believe this is a very sound approach. However, at one symposium I attended, certain community leaders focused solely on condemning the Communist Party for seizing mainland power through the war effort. They clearly exploited the commemoration as a platform for political posturing, which was deeply disappointing.

Undoubtedly, the eight-year War of Resistance exhausted the Nationalist forces while the Communists conducted propaganda and education campaigns, winning popular support. Furthermore, the Nationalist government’s corrupt and incompetent rule led to a deteriorating post-war economy, ultimately resulting in the transfer of rule in China and shaping today’s political landscape. It can be said that Japan’s invasion profoundly influenced contemporary Chinese politics. However, portraying this war solely as a calamity brought about by the Communist Party does not tell the whole story.

For those of us who grew up and were educated in Hong Kong or overseas Chinese communities with open access to information, commemorating the resistance against Japan should deepen our understanding of today’s global landscape. As for the next generation or younger cohorts, I firmly believe we bear the responsibility to preserve contemporary historical events through media. We must enable them, through education, to develop critical thinking skills and uncover the truth of history.

Mr. Raymond Chow

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October 2025

Features

History Written Under Control: Comparing East and West, and Resisting Twisted Narratives

Published

3 days agoon

October 23, 2025

East And West’s Different Historical Views

History helps us understand and learn from the past. Most people agree that it is important, but the way Eastern and Western countries record history can be very different. These differences can cause confusion, disagreements, or even disputes over what really happened.

With the rise of digital media, how countries tell the story of WWII can be very different. China’s role in the war is described in various ways, showing how the media can sometimes twist history with propaganda or misinformation. We hope to cite examples of how the role of China in WWII has been documented differently, in order to detail the importance of the media’s role in twisting historical events through propaganda and disinformation.

First, China and Western countries record history differently. In the West, historical documents are stored in archives, and writers can usually record events freely. In contrast, historical China relied on a chain of official historians who copied records left earlier dynasties to write about the past dynasty. These recording historians couldn’t openly record events that will criticize the then emperors (such as iron fist rulership), as doing so could put them and their families in danger or even get exterminated.

Of course, Western history isn’t perfect either. From an outsider’s point of view, people often see the same events differently, even on how a country is invaded. For example, any elderly Chinese might strongly defend China’s actions in the Sino-Japanese wars, while western scholars may consider many factors like land disputes, political conflicts, and ideology when explaining about the war.

Western countries often value knowledge and individual thinking for everyone. China, on the other hand, has a long history of centralized control over information. Even before printing technology was established, China had a unified written language and centralized monitored historians, to allow government control on how history was recorded. Japan had a central government too, but regional differences in culture and record-keeping still existed. Smaller countries like Laos relied more on local communities and oral traditions to preserve historical records. These examples show that whether a society values individualism or collectivism can greatly affect how history is written and remembered.

Because of this difference, history can easily be twisted when personal or political interests are involved. Today, traditional historians are fading into the sunset, slowly being replaced by 24/7 news media. If countries continuously presenting biased or incomplete versions of events, the public’s understanding becomes confused and biased. Governments or storytellers may ignore events that don’t fit their desired narrative, leaving important truths hidden.

China’s current education on the Sino-Japanese Wars

For example, Chinese textbooks often present the CCP as the main force leading the fighting against the Japanese, but that’s not entirely accurate. The Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek actually led the early efforts, reluctantly joining forces with the CCP after the Xi’an Coup. In fact, Japan’s invasion of China began earlier than the 1937 Lugou Bridge / Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The CCP often blames Manchukuo for allowing the Japanese army in invading Manchuria, but this reflects only part of the truth. While the Manchurians had some influence over that area, Manchuria was controlled by warlords, not the central Chinese government, that was Republic of China at that time. Puyi, the puppet leader, was influenced by advisors to took money from Japan and became a puppet. Looking at events from different perspectives shows how interpretations can be distorted. For example, one could ask: what if Chiang Kai-shek delayed action to avoid alerting the enemy? Even small changes like this can shape how we view the invasion’s seriousness.

The CCP also emphasizes that Chinese soldiers fought bravely while Western countries refused to help. Their narrative suggests that foreigners only cared about land and resources of China, but that’s only partly true. Britain did pressure the Qing dynasty to give up Hong Kong, but European countries and the USA avoided sending troops mainly for diplomatic reasons. Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, sending forces to China could have risked a more extensive war with Japan. Instead, the West provided weapons and supplies to the Nationalist government at that time. In hindsight, this situation is somewhat similar to the recent, three year-long Russian-Ukraine war.

The Tale of Australian William Donald

CCP influence has affected global perceptions, leading some Western countries to avoid independent research. Many Australians, for example, are unaware that some of their citizens had played key roles in the War in China with Japan. One notable figure is the Australian journalist William Henry Donald, who was deeply involved.

Donald started as a journalist and foreign correspondent before becoming an advisor of the Nationalist government in China. During the 1911 Revolution, he helped Dr Sun Yat-sen’s short-lived government negotiate with foreign powers, moving beyond reporting to active mediation. Initially, Donald admired Japan and even received a Japanese honour for his coverage of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). By 1915, however, he criticized Japanese imperialism and warned the West about its expansionist actions.

Donald played a crucial role during the Xi’an Coup, mediating between major Chinese leaders. His efforts helped secure Chiang Kai-shek’s release and the formation of a reluctant alliance with the CCP. Later, he disagreed with Chiang in 1940 over policy toward Germany. During the Pacific War, Donald was captured in Manila in 1942 but was freed in 1945. Afterward, his influence gradually declined.

Despite his decades-long involvement, historians have largely overlooked Donald’s contributions, whether advising Chiang, mediating coups, or supporting Dr Sun Yat-sen. His role is complex and less dramatic than headlines like “Chiang vs. Mao” or “Japan Invades”, so it is often ignored. In Australia, documentation about him is limited, with primary sources stored in China or specialized archives. Because Australian history education focuses more on colonial and ANZAC history, Donald’s contributions have faded from public awareness.

Chinese authorities rarely highlight Donald either. He was not a combat hero, and his advisory role could be politically inconvenient. The CCP tends to downplay internal compromises or foreign contributions, focusing instead on its own post-war achievements. Even in normal broadcasting, the media celebrating China’s journey post-war isn’t too different.

How CCP Centralization Affects Historical Documentation

Unlike many Western countries, which value history for education and heritage, China often emphasizes national pride over strict accuracy. This approach leaves younger generations unaware or unwilling to question historical events. The CCP has used systematic omission and withdrawal of all related records— sometimes called ‘amnesia therapy’ (失憶治療法) by scholars — to hide uncomfortable truths, like the Tiananmen Square Massacre. By controlling school curricula, the party successfully shapes collective memory, erasing or reframing events to suit its narrative.

In contrast, Western countries often debate controversial history publicly, offering multiple perspectives for critical analysis. The CCP also shapes views of other nations, like Japan, portraying it as a continued threat even though imperialism has ended. These examples show that history is rarely objective; it can be twisted to serve political goals. Recognizing these distortions is vital for developing critical thinking in future generations.

The CCP’s indoctrination is well-known but not unique in Asia. Postwar Japan focused on pacifism and democracy in textbooks, downplaying imperial aggression. South Korea and Taiwan have alternated between nationalist and democratic interpretations. Smaller countries like Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia relied on oral histories and local records, allowing communities to shape memory. These examples show that centralized versus decentralized record-keeping strongly affects how generations perceive the past, emphasizing that control over history shapes national identity.

Australia’s Involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War

The CCP’s influence on history goes beyond China. Cultural programs like Confucius Institutes promote party-aligned narratives internationally, shaping textbooks, museum exhibits, and media coverage abroad. Ignoring other perspectives, like those from Australia or Japan, can create a skewed understanding of WWII. This shows that controlling historical narratives isn’t just domestic indoctrination; it’s also a form of soft power.

Australia has made its own mistakes in recording history. While it doesn’t claim any credit as the CCP, it has largely hidden its involvement in China through the little-known Mission 204. In 1942, around 250 Commonwealth troops, including 48 Australians from the 8th Division, were sent to aid Chiang Kai-shek. Despite logistical difficulties and tense relations with Chinese commanders, these troops carried out successful operations, including ambushes and a notable raid on Japanese barges near Poyang Lake.

Mission 204, however, was withdrawn in November 1942 due to internal politics and health issues in the unit. Later, the Chinese Nationalist Party was forced to retreat to Taiwan by the CCP. For decades, Australia largely ignored or hid this history, only resurfacing clues in 2023. While avoiding CCP politics is understandable, it’s unfair to deny the public knowledge of Australia’s wartime actions, which effectively allows the CCP to dominate the narrative.

These examples show that celebrations of China surviving the Sino-Japanese War and WWII are often shaped by political agendas and media control. This leaves the public with incomplete, biased, or deliberately obscured views. Without critical analysis or access to multiple sources, key figures, like William Henry Donald, and events can be forgotten or misrepresented.

Viewing History Through A Critical Lens

Furthermore, whether in textbooks or news reports, the same historical events can be portrayed very differently depending on who tells the story. Motivations such as national pride, political advantage, or control over public narrative all highlight the need for careful comparative study. Governments exploit each new, impressionable generation by spreading half-truths or even outright lies under the guise of patriotism and unity. When in reality, it’s about framing themselves as ‘heroes’. The longer this continues, the fewer people will question the fabricated histories imposed by those in power.

When reading history, we shouldn’t take it at face value. What gets celebrated is rarely the full story, as many crucial voices stay buried under mainstream narratives. To avoid being misled by half-truths or polished myths, readers must take proactive steps to seek balance and truth.

For example, readers can compare news sources from different cultural backgrounds. Take the case of war survival anniversaries: a Chinese state outlet might glorify its own soldiers, while a Western outlet could focus on diplomatic strategy, such as why Western powers, despite ties with the invaded nation, chose not to intervene militarily. These contrasts reveal how bias shapes every narrative.

Another approach is to encourage counterfactual thinking, which is by exploring ‘what if’ scenarios to engage with history critically. Asking questions like “What if Chiang Kai-shek had acted sooner?” or”How might events differ if textbooks included multiple perspectives?” pushes readers to think beyond surface facts. By presenting alternative viewpoints side by side, educators and media can remind younger generations that history is layered, contested, and never entirely fixed.

News Media’s Historical Responsibilities

Additionally, should news outlets depend less on governmental sources, in order to report historical events to newer generations? For instance, the CCP often promotes itself as the sole hero in the Sino-Japanese war, overlooking many other factors that contributed to Japan’s defeat. To provide a fuller picture, journalists should consult academic historians from diverse backgrounds and archives. If local reporters are unable to do so, international media should avoid over-reliance on Chinese outlets, helping to diversify perspectives. Even when governments provide data, reporters must cross-check multiple sources: comparing war casualty numbers, dates, and accounts from different national archives.

To combat biased or incomplete narratives, media organizations must embrace investigative journalism. Rather than relying solely on press releases or government celebrations, journalists should explore archives, personal accounts, and lesser-known sources. This approach can uncover overlooked contributors, hidden controversies, or forgotten stories, such as the decades-long influence of William Henry Donald in China. Without such diligence, these stories risk being lost to history.

Other than Official Historical Narratives

Historical events are rarely one-dimensional. To ensure accuracy, news outlets should present both domestic and foreign perspectives. For instance, reporting on the Sino-Japanese War should not rely solely on CCP or Chinese Nationalist sources; Japanese accounts, Western observers, and even oral histories from survivors’ descendants can provide valuable insight. By comparing these perspectives, readers gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of events and can see where bias, pride, or self-interest has shaped narratives.

History is often told through the lens of nations, prominent leaders, or major battles, leaving countless contributors invisible. Unsung figures – nurses on the frontlines, translators bridging cultural and linguistic gaps, local militias defending communities, and ordinary civilians navigating war — have all shaped outcomes without formal recognition. Grassroots organizers and community leaders often mitigated famine, displacement, or political oppression, yet their stories rarely appear in mainstream textbooks. Highlighting these individuals challenges simplified nationalist accounts and invites readers to critically examine history from multiple angles. By including personal stories, letters, diaries, and oral histories, historians and educators can provide a richer, more nuanced understanding, showing that history is not only the story of leaders but also of ordinary people whose everyday decisions ripple across generations.

Importance of Multifaceted Historical Narrations

Historical narratives are not confined to academic debate; they actively shape contemporary geopolitics and international relations. The CCP’s control over historical interpretation has profoundly affected public perception of Taiwan, the South China Sea, Hong Kong, and Japan, often framing policies as defensive or restorative to fit a particular national narrative. Textbooks emphasizing the ‘century of humiliation’ or heroic struggles against foreign powers can reinforce domestic support for assertive policies abroad.

Understanding these manipulations shows how governments leverage history to justify policy, cultivate national sentiment, and shape international perception. Media, educational programs, and cultural diplomacy can extend this influence globally, subtly guiding how other countries interpret events involving China. Recognizing these dynamics is crucial for analysts, educators, and citizens, highlighting that history is not merely a record of the past but also a tool actively deployed to influence present-day politics and international relationships.

Digital Era’s Challenges Towards History

The landscape of historical narrative has further shifted in the digital age. Social media platforms are not just spaces for connection but arenas for ideological competition. TikTok, WeChat, YouTube, and Twitter/X have become battlegrounds for competing interpretations of history. Viral clips, memes, and algorithmically promoted content often shape perceptions more strongly than formal education. Algorithms tend to favor content that evokes strong emotions – national pride, outrage, or sensationalism – reinforcing particular viewpoints while suppressing others. Unlike these fast-moving but potentially biased feeds, traditional textbooks, though limited in perspective, are curated and vetted to ensure factual consistency.

For younger generations growing up online, cultivating media literacy, critical thinking, and the ability to cross-reference multiple sources is essential. This is not only to resist propaganda but also to engage with history in its full complexity. Encouraging discussions about the origins and credibility of online content empowers students to recognize how narrative manipulation occurs in real time. It prepares them to approach information critically throughout their daily lives.

Finally, historical reporting should be more understandable to younger generations. The media can leverage multimedia tools – short videos, infographics, timelines, and interactive articles – to break down complex events. Clear, engaging formats, using layman language and visuals, can prevent oversimplification and reduce the risk that a single, potentially biased narrative dominates public understanding.

In an age of propaganda, selective memory, and curated narratives, readers must approach history critically. By seeking multiple sources, questioning official accounts, and embracing diverse perspectives, we can resist half-truths and uncover the full story. History is not just a record of the past; it is a tool for understanding the present and shaping a more informed future. If media, educators, and citizens take these steps seriously, hidden figures like William Henry Donald and many others who shaped history behind the scenes can finally receive the recognition they deserve.

Editorial : Raymond Chow, Jenny Lun

Photo: Internet

Published in Sameway Magazine on 24 October, 2025

Features

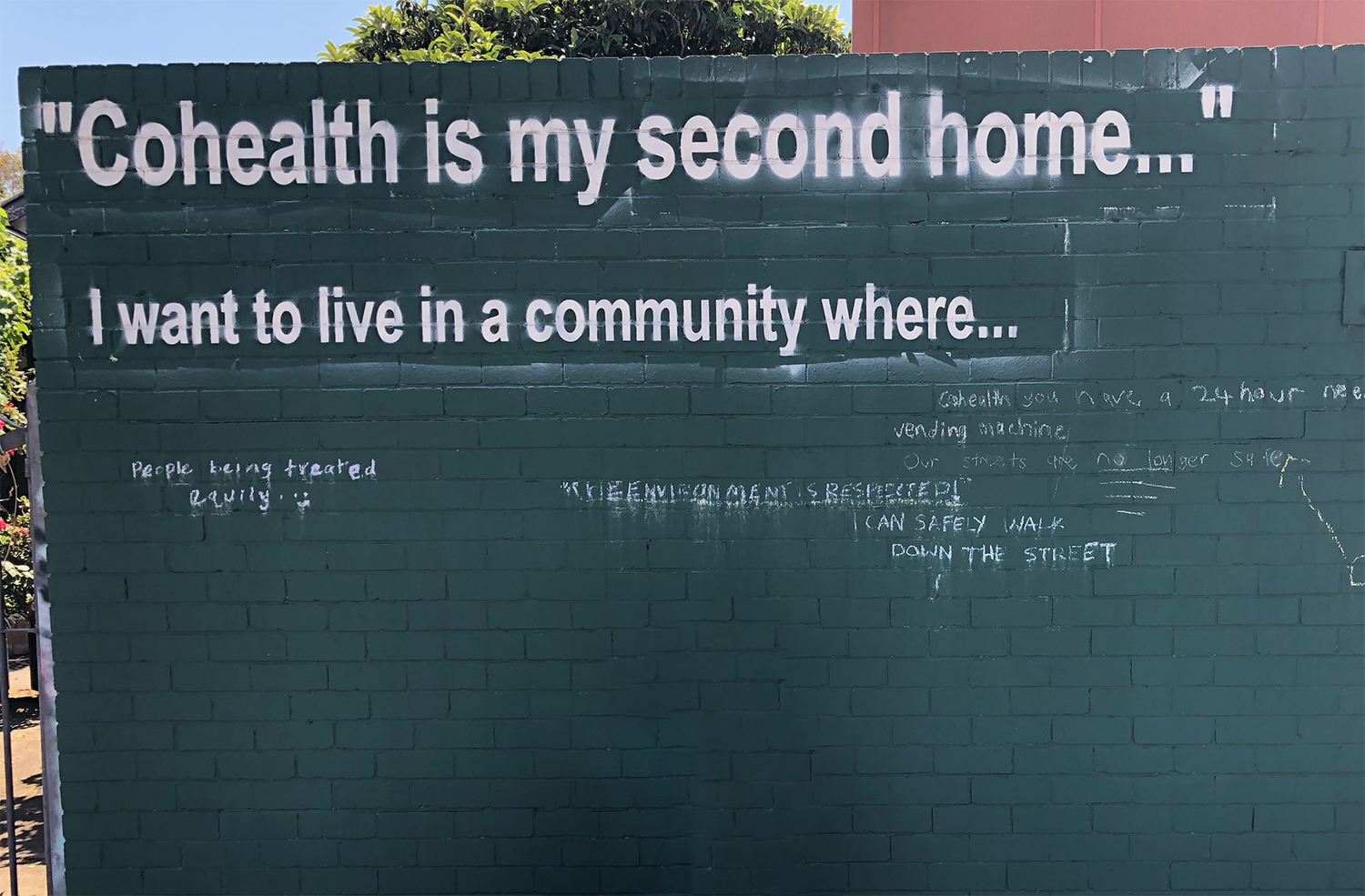

Cohealth Service Cutoff — Victorian Government Cannot Ignore

Published

3 days agoon

October 23, 2025

On October 16, Cohealth—one of Australia’s largest community health organizations and a non-profit medical institution—announced it would close three of its clinics. The news immediately sparked widespread public debate and criticism. The affected clinics are located in Collingwood, Fitzroy, and Kensington. The Fitzroy and Kensington clinics will cease general practitioner (GP) and consultation services this December, though they will continue providing specialized support for alcohol, drug, and domestic violence issues. The Collingwood centre is scheduled for full closure next June.

The closures will directly impact approximately 12,500 patients, resulting in 20 doctors losing their jobs and 44 nurses facing reassignment or redundancy. These clinics have long provided vital primary healthcare services to low-income individuals, the homeless, refugees, domestic violence survivors, and those with chronic illnesses, serving as an indispensable health support network within the community. However, due to insufficient funding, rising costs, and operational pressures, these services are now being forced to cease.

Nicole Bartholomeusz, CEO of Cohealth, stated that the cessation of services reflects “multiple and complex pressures, including decades of underinvestment, aging infrastructure, and funding models that don’t match actual needs or the type of care required.” She noted: “The funding we receive is only sufficient to provide standard care, but we actually serve high-need patients who often require extended appointments and comprehensive case management tailored to each individual.”

Cohealth’s current Medicare subsidy only covers physician salaries, failing to account for nurses, receptionists, and other operational costs. As wages and supply costs rise, the annual gap between clinic operating expenses and Medicare funding continues to widen.

Reforms Too Late, Support Too Little

In truth, Cohealth’s predicament did not emerge suddenly but resulted from years of accumulated challenges. Although the federal Labor government has pushed Medicare reforms in recent years to enhance the sustainability of the universal healthcare system—such as the upcoming Bulk Billing Practice Incentive Program (BBPIP) launching November 1st, which will expand Medicare coverage, encourage clinics to maintain bulk billing, and provide additional funding for facility upgrades and team expansion— This initiative aims to improve access and affordability of healthcare services, with approximately 4,800 clinics expected to benefit.

However, for Cohealth, this reform appears to have come too late. The root problem lies not solely at the federal level, but in the Victorian government’s long-standing neglect of the actual health needs within grassroots communities. The poverty, homelessness, addiction, and trauma issues plaguing local communities have long exceeded the capacity of standard clinics. Yet the Victorian government has failed to provide additional support or establish stable funding mechanisms to sustain non-for-profit healthcare providers.

Cohealth identifies two primary causes for the current crisis: First, insufficient Medicare funding from the federal government for managing complex patients; Second, the Victorian government has failed to fund upgrades for the aging facilities at the Collingwood clinic.

Cohealth has repeatedly called for government support over the years. As early as 2022, Cohealth issued a statement noting that while they supported the government’s health-focused budget, the community health model—which played a critical role during the pandemic—was once again being overlooked. At that time, Cohealth emphasized the need for comprehensive investment across the entire healthcare sector to strengthen the health system as a whole.

The clinic’s facilities have long been outdated, with roof leaks forcing appointment cancellations. Despite multiple funding applications to authorities over the years, no substantive response has been received. Infrastructure Victoria’s report highlights that government funding for community services is fragmented and inadequate. The federal government has yet to establish dedicated funding for community health infrastructure. Even though the Australian government allocated $117 billion to health and medical services for 2024-25, community health organizations received only 0.3% of Victoria’s annual health infrastructure expenditure of approximately $2 billion.

Amid chronic funding shortages and sluggish government reforms, the state government’s disregard for community needs and inaction ultimately sealed the fate of these clinics. This underscores the state government’s core responsibility in ensuring the continuity of primary healthcare services.

Who is accountable for healthcare quality and service delivery?

In fact, community healthcare systems did not originate from government initiatives but from charitable and faith-based traditions. Early hospitals were often founded by churches or charitable organizations with a simple mission: to provide basic care to the poor and vulnerable through empathy and compassion. Healthcare then embodied social conscience rather than being a product of policy or systems.

As society modernized and public health concepts emerged, governments gradually assumed responsibility, incorporating health into the realm of “public duty.” The original intent behind this shift was noble—to ensure equal access to healthcare for all. Yet the process of institutionalization and bureaucratization introduced new challenges: the original “people-centred” care became diluted by layers of administrative procedures and economic logic. Healthcare services increasingly emphasized efficiency and output, gradually losing its human warmth.

Non-profit medical institutions like Cohealth represent a continuation of this historical trajectory. They uphold the founding spirit of charitable healthcare—serving vulnerable communities while upholding the belief that everyone deserves the right to health and equal access to medical care. Yet in reality, these organizations rely on government subsidies and unstable funding sources to sustain their operations.

The contradiction lies in the fact that as societies grow wealthier, public healthcare systems should be better equipped to protect the vulnerable. Yet the opposite occurs: medical costs rise relentlessly, resource distribution grows increasingly unequal, and healthcare services become ever more commoditized. In this environment, doctors are forced to complete consultations within “six-minute appointments,” nurses and receptionists operate at breaking point, and patients slip through the cracks of the system, overlooked.

Yet when reflecting on responsibility, the question may extend beyond “Who is to blame?” to “Where should healthcare be headed?”

Should we pursue the endless quest to “cure every disease”? Or should we return to healthcare’s fundamental purpose—ensuring everyone accesses basic health protection?

When the wealthy pay more for faster, better care while the poor endure long queues, has the ideal of equality already been swallowed by market logic?

Take Hong Kong, for instance. As a low-tax society, its citizens enjoy public healthcare at minimal cost—subsidized for life simply by holding a Hong Kong ID card. However, with an aging population and healthcare staff shortages, the public system has been chronically overburdened, leading to months-long waits for emergency rooms and specialist appointments. Consequently, the affluent middle and upper classes turn to private clinics, trading money for efficiency. This creates a healthcare system that appears equitable on the surface but is fundamentally stratified: the government guarantees access to services but not equal speed or quality. In other words, everyone has the right to medical care, but whether you can get better quickly and where you receive treatment depends on how much money you have.

Canada’s public healthcare system, meanwhile, is more idealistic. All residents can access free public healthcare with a health card, free from concerns about high costs. However, long waiting times and uneven resource distribution transform “free” into another form of “cost.” When demand far exceeds supply, fairness and accessibility inevitably clash.

Moreover, should healthcare prioritize “universal access” or ‘quality’? Should governments provide “basic care” or “comprehensive coverage”?

Comparisons with China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan

From an international perspective, Australia’s public healthcare system (Medicare) differs significantly from those in mainland China and Taiwan, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages. Mainland China’s system, dominated by public hospitals, subsidizes basic care through social medical insurance (urban employee/resident insurance). However, due to its massive population and concentration of medical resources in major cities, primary community clinics often struggle to handle high-demand patients—particularly low-income groups and those with chronic conditions. This mirrors Cohealth’s current situation: “resource concentration leading to overflowing demand.”

Taiwan adopted a National Health Insurance (NHI) model emphasizing “one health insurance card, nationwide healthcare coverage,” ensuring basic medical services for all regardless of urban/rural location or income level. NHI strengthens primary care clinics through subsidies and incentives, stabilizing the family doctor system. Nevertheless, disparities in healthcare resource distribution between urban and rural areas persist, and wait times for specialist care can remain excessively long.

In contrast, Australia’s Medicare system pursues fairness and accessibility in theory. Yet in practice, non-profit primary care institutions face chronic funding shortages and aging facilities. While serving predominantly vulnerable populations, these clinics often shoulder service volumes exceeding subsidy coverage. This structural contradiction creates a significant gap between the system’s ideals and its actual service capacity, highlighting a common challenge faced by vulnerable groups under different systems: even with “systemic safeguards,” they may still be marginalized due to inadequate resource allocation.

Australia’s Core Healthcare Contradiction

Returning to Australia itself, the core issue of its healthcare system isn’t a lack of total funding, but rather structural contradictions arising from resource allocation, institutional design, and policy priorities. Medicare is primarily designed for “standard medical services” such as general consultations, basic tests, and medications. However, it does not provide corresponding subsidies for the time, labour costs, and interdisciplinary integrated care required for high-need or complex patients. This leaves vulnerable groups unable to access truly comprehensive healthcare under the existing system.

Non-profit community clinics like Cohealth exist precisely to fill this gap. They offer extended consultations, case management, mental health counselling, addiction and domestic violence support, and even multidisciplinary integrated programs—services standard GP clinics struggle to provide. However, these intensive services are not fully subsidized by Medicare. Combined with limited state investment in primary care infrastructure, clinics face chronic financial strain, ultimately forcing service reductions or partial closures.

Cohealth’s partial closures reflect a deep-seated contradiction within Australia’s healthcare system: equity and accessibility do not equate to substantive care guarantees for high-need populations. While everyone ostensibly has the right to medical care, those requiring prolonged attention and individualized management often survive only by navigating systemic gaps. The institutional design itself thus creates an “invisible inequity” for high-need patients.

Australia’s healthcare also grapples with the dilemma of balancing universal coverage and quality. On one hand, the system must ensure everyone receives at least basic treatment; on the other, complex patients require sufficient time, specialized support, and case management. In reality, however, insufficient government funding and a narrow subsidy structure make achieving both goals difficult. Doctors are forced to rush through consultations, nurses and receptionists operate at capacity, while vulnerable patients languish on waiting lists. Non-profit clinics like Cohealth strive to fill these gaps, but persistent financial pressures and policy constraints render “humanized healthcare” a luxury in practice.

In other words, the core issue with Australia’s public healthcare system isn’t merely about assigning responsibility, but whether the system can return to its founding principle: ensuring everyone accesses basic healthcare while providing high-need patients with adequate resources and compassionate support when required. Cohealth’s predicament serves as a stark warning: without structural adjustments to resource allocation by government and society, the ideal of fairness remains unattainable, and vulnerable groups will continue to be marginalized by the system.

The Victorian Government’s Indisputable Responsibility

While medical policy is set by the federal government, state governments bear responsibility for implementing it according to local realities. Cohealth’s inner-city service area has a population receiving government living subsidies that exceeds the Australian average by more than double, indicating many residents cannot afford private services. The Victorian Government’s refusal to provide financial support to institutions like Cohealth demonstrates a disregard for vulnerable communities.

A similar situation exists in elder care for multicultural communities. While federal funding supports aged care services, research indicates that non-English-speaking seniors benefit most from living in facilities that accommodate their cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Yet, emerging senior communities like the Chinese diaspora receive minimal Victorian government assistance to build suitable aged care facilities. Since 2014, Labor leader Andrews has repeatedly proposed policies to purchase four plots of land for the Chinese and Indian communities to build elderly care facilities. Yet to this day, the Victorian Department of Health continues to leave these sites vacant, failing to hand them over to community organizations to develop services. This demonstrates a dereliction of duty by government officials. This situation bears striking similarities to Cohealth Community Health Services ceasing operations today due to neglect. Should the Victorian Government conduct a thorough review of the Department of Health’s operations?

Editorial : Liz Li, Jenny Lun

Photo: Internet

Published in Sameway Magazine 24 October 2025

Listen Now

October – History

History Written Under Control: Comparing East and West, and Resisting Twisted Narratives

Cohealth Service Cutoff — Victorian Government Cannot Ignore

Anthony Albanese Meets Trump to Discuss Minerals, Defense, and Trade

Louvre Jewelry Heist Steals Historic Treasures

Fraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

Cantonese Mango Sago

FILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

U.S. Investment Report Criticizes National Security Law, Hong Kong Government Responds Strongly

China Becomes Top Destination for Australian Tourists, But Chinese Visitor Return Slows

What Is the Significance of Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan’s First Visit to China?

Albanese Visit to UK Focuses on Domestic Reform, Not Republican Debate

Optus Faces Another “000” Outage, Singtel Bonus Sparks Controversy

Trending

-

COVID-19 Around the World4 years ago

COVID-19 Around the World4 years agoFraudulent ivermectin studies open up new battleground

-

Cuisine Explorer5 years ago

Cuisine Explorer5 years agoCantonese Mango Sago

-

Tagalog5 years ago

Tagalog5 years agoFILIPINO: Kung nakakaranas ka ng mga sumusunod na sintomas, mangyaring subukan.

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years ago如果您出現以下症狀,請接受檢測。

-

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago

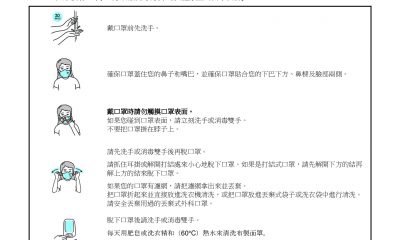

Cantonese - Traditional Chinese5 years ago保护您自己和家人 – 咳嗽和打喷嚏时请捂住

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoCOVID-19 檢驗快速 安全又簡單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

在最近的 COVID-19 應對行動中, 維多利亞州並非孤單

-

Uncategorized5 years ago

Uncategorized5 years agoHow to wear a face mask 怎麼戴口罩